|

|

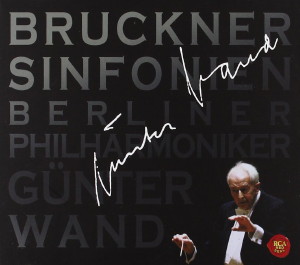

6 CD's

- 88691922952 - (c) 2011

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 4 in E flat major "Romantic"

- 2. Fassung 1878/1880 (WAB 104) |

|

68' 40" |

CD 1 |

| -

1. Bewegt, nicht zu schnell |

19' 09" |

|

|

| -

2. Andante quasi Allegretto |

15' 58" |

|

|

-

3. Scherzo: Bewegt - Trio. Nicht zu

schnell, keinesfalls schleppend

|

11' 14" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

21' 50" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 5 in B flat major - Originalfassung

(WAB 105) |

|

76' 52" |

CD 2 |

| -

1. Introduktion (Adagio) - Allegro |

21' 31" |

|

|

| -

2. Adagio (Sehr langsam) |

16' 26" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo. Molto vivace (Schnell) |

14' 20" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale. adagio - Allegro moderato |

24' 57" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 7 in E major - Originalfassung

herausgegeben von Robert Haas (WAB

107) |

|

66' 35" |

CD 3 |

| -

1. Allegro moderato |

21' 06" |

|

|

| -

2. Adagio. Sehr feierlich und sehr

langsam |

21' 44" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo. Sehr schnell |

10' 33" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale. Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

13' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 8 in C minor

- 1890 Originalfassung

herausgegeben von Robert Haas (WAB

108) |

|

87' 07" |

|

-

1. Allegro moderato

|

17' 03" |

|

CD 4 |

-

2. Scherzo: Allegro moderato &

Trio: Langsam

|

16' 07" |

|

CD 4 |

| -

3. Adagio. Feierlich langsam, doch

nicht schleppend |

27' 36" |

|

CD 5 |

| -

4. Finale. Feierlich, nicht schnell |

26' 21" |

|

CD 5 |

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 9 in D minor

- Originalfassung (WAB 109) |

|

61' 59" |

CD 6 |

| -

1. Feierlich, misterioso |

26' 12" |

|

|

| -

2. Scherzo. Bewegt, lebhaft - Trio.

Schnell |

10' 35" |

|

|

| -

3. Adagio. Langsam, feierlich |

25' 12" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

| Günter WAND |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Philharmonie,

Berlin (Germania):

- 30-31 gennaio & 1 febbraio

1998 (Symphony No. 4)

- 12, 13 & 14 gennaio 1996

(Symphony No. 5)

- 19-21 novembre 1999 (Symphony

No. 7)

- 19-22 gennaio 2001 (Symphony No.

8)

- 18 & 20 settembre 1998

(Symphony No. 9)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recordings

|

|

|

Producer |

|

Gerald

Götze (No. 4, 5, 7, 8, 9)

|

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Christian

Feldgen (No. 4, 5, 7, 8, 9) |

|

|

Executive Producer |

|

Dr.

Stefan Mikorey (No. 4, 5, 7, 8, 9)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

SONY

[RCA Red Seal] - 09026 68839 2 -

(1 CD) - (p) 1998 - DDD -

(Symphony No. 4)

SONY [RCA Red Seal]

- 09026 68503 2 - (1 CD) - (p)

1997 - DDD - (Symphony No. 5)

SONY

[RCA Red Seal] - 74321 68716 2 -

(1 CD) - (p) 2000 - DDD -

(Symphony No. 7)

SONY

[RCA Red Seal] - 74321 82866 2 -

(2 CD's) - (p) 2001 - DDD -

(Symphony No. 8)

SONY

[RCA Red Seal] - 74321 63244 2 -

(1 CD) - (p) 1999 - DDD -

(Symphony No. 9)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PERFECTION

WHAT

MAKES THIS CONDUCTOR

ESPECIALLY SUCCESSFUL AT THE

PODIUM? Posed another wav,

how and with what does he

reach such extraordinary

results, and not only with

Bruckner? With what does he

cause this breathtaking

degree ot naturalness?

Immediately, one has to

state that Wand did not do

anything that was not

necessary. But what makes

Wand special begins there,

that he finds much necessary

that others disregard. Above

all, he always gives himself

the time, often a lot of

time, to get close to a

composer or to a certain

work. For Bruckner and

Schubert, Wand took many

years before he tried

certain symphonies, the

great Schubert’s C Major at

60 and Bruckners “Fifth” at

62. That certainly was not

because of the technical

problems (he had never had

these as conductor), but was

a question of his getting

intellectually close to this

great music. But also for

works which he had already

directed many times, he

prepares for weeks, many

times months for a certain

program. He started to work

long before the first

rehearsal. With his unique

thoroughness he delved into

the work in orderto present

it so that the public has

the feeling that it can not

be otherwise. Therefore Wand

first studied the score,

whether it be a familiar

work or not, reading it and

hearing it again and again.

Naturally, he also read

biographies and letters of

the composers, delved into

the story of the creation of

the work and the history of

the premiere. The score was

always at the center of the

work. If he doubted the

exactness of the notation or

the verbal instructions, he

studied the sources,

compared with the autograph

and the first edition

supervised by the composer.

Only when the notes and the

instructions became clear to

him did he start with the

“setting up” of the score

and the leading voices, that

is, with the sketching of

articulations, phrasing and

dynamics. They are

transferred to collective

orchestra voices and this

before the first rehearsal.

The effect of this

preparation is not only that

Wand had a thorough command

of the work but, above all,

that he could devote 100% of

the rehearsal time to the

valuable musical work and,

in contrast to the usual

practice, can do without

important entering certain

points of completion. For

example, four beats after

letter G, the 2nd oboe has

to play mezzo forte so that

the balance fits, was known

to the musicians in a Wand

orchestra even before they

play the passage. From the

first rehearsal on,

rehearsals mostly divided

into orchestra groups (i.e.

separate for strings and

winds), Günter Wand worked

“precisely” (as his

musicians in Cologne called

it) until each detail fit

and the whole agrees with

his idea of “correct.” This

way he saved words, with

explanation. In general,

orchestra musicians did not

like this but they accept it

from him because he, like an

author, “has something to

say." In his later years

Wand pursued this rather

with soft, irresistible

persistence stubbornness

than with the feared

outbursts of anger of his

young years.

When a soloist came, which

did not happened often in

the later years, working

together in each detail was

discussed and rehearsed.

During his Cologne years

this personal meeting of the

minds took place in Wands

private apartment; in

Hamburg it was in the

artist’s dressing room at

NDR or the conductor's room

at the Musikhalle. Whoever

did not agree was not

invited again. Great artists

like Wilhelm Backhaus, Clara

Haskil, Henryk Szeryng,

Wolfgang Schneiderhan or

Nikita Magaloff came to him

again and again simply

because they found Günter

Wand a congenial partner

with whom they could work as

with none other. Because he

knew that satisfying music

making can be reached not

through forced subordination

to the conductor will but

only in the harmony between

orchestra and conductor. He

valued that all

participating musicians,

whether as soloist or in the

last row internally accepted

his idea of the work.

Therefore, a rehearsal

always meant convincing for

him as well. The members of

the Berliner Philharmonic,

musicians who knew the

symphonic repertoire inside

out and commanded it by

heart, found that Wand's

rehearsals makes sense for

them because he also has

something to say to the most

experienced and practiced

musicians. It is no wonder

that in his concerts even

the most well-known

symphonies work as new, that

to him, the older he became,

the more he succeeded was

can to be heard on each one

of his live CDs.

But there is still more

perceptible here. This is

the difference between

rehearsal and concert.

Günter Wand went onto the

concert platform with his

orchestra, as well prepared

as possible. Everything is

precisely worked out and

could almost run

automatically. Still, then

came the famous “magic

extra" of the evening, the

emotional interaction

between musicians, conductor

and audience. That the

musicians understood what he

wanted and wanted to play

their parts accordingly has

been accomplished in the

rehearsals. Now in the

concert it was important

that the listener heard

senses in and behind the

notes. He made music with an

inner fire, however, he did

not conduct "for effect"

much like many others. His

musicians confirmed this

again and again. But there

was something he wanted to

accomplish, namely that the

public was spoken to

inwardly through the music

and mrrsic rnaking. And he

succeeded in the fact that

he transformed his strict

rehearsal style into live

sound with spontaneous

impulses of emotional

freedom which come from the

heart. One of his Hamburg

musicians once made in the

point. “Wand makes music not

externally but internally,

and this in the highest and

most brilliant manner. His

musicianship has

authenticity."

Günter Wand did nothing on

the concert platform which

was not technically

necessary. He kept time

“with a minimum of gestures

and body language," so

precise that the musicians

could feel secure even in

the most difficult passages.

There was no doubt how a

ritardando or a diminuendo

should be played or a sudden

accent is to be placed. Wand

led so unobtrusively exact

that nothing could go wrong.

Again and again the critics

had tried to explain it and

had asked how it is possible

to reach so much (with so

few motions). Manual

perfection, thoroughly

worked out and practiced in

seven decades as conductor,

was obviously a prerequisite

to this man for emotionally

full music making. Therefore

he also had the score in his

head not on the podium. For

anyone who had again and

again experienced Wand

concerts, the enormous

vitality and concentrated

energy that came from this

and fragile body was

amazing. The complete,

highly sensitive man

vibrated to the pulse of the

music, as his body sensed

the basic tempo and mirrors

in return. With it, he gave

the orchestra musicians

extra signals. Günter Wand

had control of the musical

event so that the musicians

play under his direction

works simply “corrected” as

it there were no alternative

aesthetic.

Since his seventieth year,

Günter Wand had been

regarded undisputedly as the

great old man of the baton,

as one of the last in a

series from Toscanini,

Furtwängler and Klemperer

and as the perhaps most

important conductor of our

time. What he once said

about Otto Klemperer of one

who had the feeling of

living in a “ridiculous

time," can also be true of

him as well; “In a world of

tragic occurrences he stands

for the importance of

being." With advanced age,

Günter Wand, the great

timeless one who adhered to

his results unwaveringly,

had become the revered

figure whose musical

competence no one doubted.

He was respected, admired

and loved, (which indeed is

not received by every

conductor) by the musicians.

Also young and old

colleagues from Japan,

Russia, and England sought

his advice, coming to his

rehearsals whenever possible

in order to learn from him.

When he sensed real interest

and musical engagement, he

allowed them to come with

pleasure. Indeed, a

respected conductor like Sir

Simon Rattle (and who made

his City of Birmingham

Symphony Orchestra great as

Wand did that Cologne

Gürzenich Orchestra) cites

Wand as his greatest role

model and missed no chance

to hear him in Hamburg,

Berlin or Edinburgh and to

discuss music and music

making with him. “Since I

got to know Günter Wand, my

life has become a dimension

richer."

Günter Wand had always

understood his profession as

that of a servant. He never

saw himself in the role of a

“podium magician" appearing

in mysterious ways as a

personal medium between

music and audience. For him,

directing was for service to

the music, service to the

work of the composers and

not the chance to engage in

excessive

self-representation. He

never regarded an

interpretation as the

perfect conclusion to his

occupation with the work,

never considered an

interpretation as final.

Also, even after the

greatest success he

immediately continued

working. Perhaps Wand had

become such a singular

figure in the musical life

of our times because of this

consequent attitude which

challenges a comparison with

his great predecessors.

Wolfgang

Seifert

(Translation:

Kevin Wood)

|

|

|

|