|

|

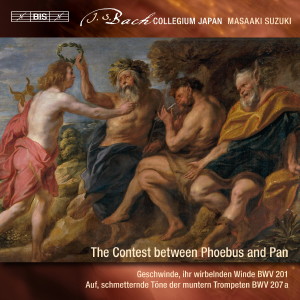

1 CD -

BIS-2311 SACD - (p) 2017

|

|

SECULAR

CANTATAS - Volume 9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dramma per musica. Der Streit

Zwischen Phoebus und Pan

|

|

|

|

| "Geschwinde, ihr

wirbelnden Winde", BWV 201 |

|

47' 32" |

|

| Tromba I, II, III,

Timpani, Flauto traverso I, II, Oboe

I, auch Oboe d'amore, Oboe II, Violino

I, II, Viola, Soprano (Momus), Alto

(Mercurius), Tenore I (Tmolus), Tenore

II (Midas), Basso I (Phoebus), Basso

II (Pan), Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Geschwinde, ihr

wirbelnden Winde... |

5' 34" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso I, Basso II,

Soprano): Und du bist doch so

unverschämt und frei... |

1' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Patron, das

macht der Wind... |

2' 31" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Alto, Basso I, Basso

II): Was braucht ihr euch zu

zanken... |

0' 53" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso I): Mit Verlangen

drück ich deine zarten Wangen... |

9' 00" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano, Basso II): Pan,

rücke deine Kehle nun... |

0' 20" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso II): Zu Tanze, zu

Sprunge, so wackelt das Herz... |

5' 23" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Alto, Tenore I): Nunmehro

Richter her... |

0' 45" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore I): Phoebus, deine

Melodei... |

5' 50" |

|

|

| - Recitativo

(Basso II, Tenore II): Komm,

Midas, sage du nun an... |

0' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore II): Pan ist

Meister, lasst ihn gehen!... |

4' 41" |

|

|

| - Recitativo

(Soprano, Alto, Tenore I, Basso I,

Tenore II, Basso II): Wie,

Midas, bist du toll?... |

1' 04" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Alto): Aufgeblasne

Hitze... |

5' 39" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Du guter

Midas, geh nun hin... |

1' 05" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Labt das Herz, ihr

holden Saiten... |

2' 21" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dramma per musica.

Glückwunschkantate zum Namenstage

Augusts III (Uraufführung: 03.08.1735)

|

|

|

|

| "Auf,

schmetternde Töne der muntern

Trompeten", BWV 207a |

|

32' 30" |

|

| Tromba I, II, III,

Timpani, Flauto traverso I, II, Oboe

d'amore I, II, Taille, Violino I, II,

Viola, Soprano, Alto, Tenore,

Basso,Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Auf, schmetternde Töne

der muntern Trompeten... |

4' 38" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Tenore): Die stille

Pleiße spielt... |

1' 58" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore): Augustus'

Namenstages Schimmer... |

3' 22" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): Augustus'

Wohl ist der treuen Sachsen

Wohlergehn... |

2' 00" |

|

|

| -

Aria: Duetto (Basso, Soprano): Mich

kann die süße Ruhe laben... |

6' 21" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Alto): Augustus

schützt die frohen Felder... |

0' 53" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Alto): Preiset, späte

Folgezeiten... |

5' 25" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Tenore, Basso, Soprano,

Alto): Ihr Fröhlichen,

herbei!... |

2' 46" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: August lebe, lebe,

König!... |

3' 34" |

|

|

| -

Anhang: Marche |

1' 25" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joanne Lunn, soprano

(BWV 201 Momus, BWV 207a)

|

BACH COLLEGIUM

JAPAN / Masaaki Suzuki, Direction

|

|

| Robin Blaze,

counter-tenor (BWV 201 Mercurius, BWV

207a) |

- Jean-François

Madeuf, Tromba I |

|

| Nicholas Phan,

tenor (BWV 201 Midas, BWV 207a) |

- Joël Lahens, Tromba

II |

|

| Katsuhiko

Nakashima, tenor (BWV 201 Tmolus) |

- Hidenori Saito, Tromba

III |

|

| Christian Innler,

baritone (BWV 201 Phoebus) |

- Atsushi Sugahara,

Timpani |

|

| Dominik Wörner,

bass (BWV 201 Pan, BWV 207a) |

- Kiyomi Suga, Flauto

traverso I |

|

|

- Liliko Maeda, Flauto

traverso II |

|

| Kizomi Suga, flauto traverso |

- Masamitsu

San'nomiya, Oboe I, Oboe d'amore |

|

| Masamitsu

San'nomiya, oboe,

oboe d'amore |

- Go Arai, Oboe

II, Oboe d'amore II |

|

|

- Ayaka Mori, Taille |

|

| CHORUS |

- Ryo Terakado, Violino

I leader |

|

| Soprano: |

- Natsumi Wakamatsu,

Violino I |

|

| Joanne Lunn,

Minae Fuijisaki, Aki Matsui, Eri Sawae |

- Yuko Araki, Violino

I |

|

| Alto: |

- Azumi Takada, Violino

II |

|

| Robin Blaze,

Hiroya Aoki, Tamaki Suzuki, Chiharu

Takahashi |

- Yuko Takeshima, Violino

II |

|

| Tenor I: Katsuhiko

Nakashima, Taiichiro Yasutomi |

- Ayaka Yamauchi, Violino

II |

|

| Tenor II: Nicholas

Phan, Yusuke Fujii |

- Hiroshi Narita, Viola |

|

| Basso I: Christian

Immler, Chiyuki Urano |

- Akira Harada, Viola |

|

| Basso II: Dominik

Wörner, Yusuke Watanabe |

|

|

|

Continuo: |

|

|

- Toru Yamamoto, Violoncello |

|

|

- Takashi Konno, Violone |

|

|

- Kiyotaka Dosaka, Fagotto |

|

|

- Masaaki Suzuki, Cembalo |

|

|

- Masato Suzuki, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kobe

Shoin Women's University Chapel

(Japan) - September 2016 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer | Engineer |

|

Thore

Brinkmann (Take5

Music Production) |

Matthias Spitzbarth | Akimi

Hayashi |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BIS -

BIS-2311 SACD - (1 CD) - durata

80' 53" - (p) & (c) 2017 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| COMMENTARY

|

Geschwinde,

ihr wirbelnden

Winde, BWV 201 (Hurry,

Ye Whirling Winds)

The Contest

between Phoebus

and Pan

Whereas the majority

of Bach’s secular

cantatas were

written for specific

political, academic

or private festive

occasions, which are

emphasized by their

texts, in the case

of the ‘dramma per

musica’ Geschwinde,

ihr wirbelnden

Winde no

particular cata lyst

is discernible. It

may well be that

Bach composed the

piece on his own

initiative, without

an external

incentive,

especially because

the message he

conveys in the work

can be understood as

championing his own

cause – a defence of

his artistry and his

musical attitudes

against the trends

of the time, against

philistinism,

superficiality of

artistic judgement

and an unquestioning

preference for easy

fare.

The score and parts

date from 1729. The

introductory chorus

urges the ‘whirling

winds’ to withdraw

to the ‘cave’ so

that the music may

remain undisturbed,

suggesting that the

music was performed

in late summer or

early autumn.

According to the Aeneid

by Virgil (70–19 BC)

Aeolus, god of the

winds, kept the

powerful autumn

storms captive in a

cave, releasing them

only when the time

was right. Evidently

the people of

Leipzig were hoping

for good weather for

an outdoor

performance.

The work is

remarkable for its

opulent scoring,

with no fewer than

six vocal soloists,

plus trumpets and

timpani, flutes,

oboes, strings and

continuo. Bach had

recently taken over

leadership of the

Leipzig Collegium

musicum, founded by

Telemann, and could

evidently indulge

himself.

The libretto was by

Bach’s regular and

skilful

collaborator,

Picander (i.e.

Christian Friedrich

Henrici [1700–64)].

It alludes loosely

to a famous episode

from the Metamorphoses

by Ovid (43 BC – 17

AD), describing a

musical competition

between two Greek

gods. Pan, the god

of shepherds and

flocks and companion

of the nymphs, with

his own invention,

the panpipes,

challenges Phoebus

(Apollo), the

cithara-playing god

of the arts, to a

contest. They are

accompanied by their

seconds, the Lydian

mountain god Tmolus

and the Phrygian

king Midas. Phoebus

and Pan compete and,

as might have been

expected, Phoebus

emerges victorious.

Midas, however, had

voted for Pan; and

he is now punished

by Phoebus, who

gives him donkey

ears.

Picander’s libretto

turns the

instrumental

competition into a

singing contest. Two

additional

characters join in

as well: Momus, the

god of mockery, and

Mercury, the

versatile messenger

of the gods, who as

the patron of

merchants was a

familiar

mythological figure

in the trade fair

city of Leipzig. To

some extent it is

these two characters

who drive the action

forwards.

Bach divided up the

vocal pitches into

pairs. Momus and

Mercury are

allocated to the

upper voices,

soprano and alto;

the ‘seconds’ Tmolus

and Midas sing first

and second tenor,

and the protagonists

Phoebus and Pan sing

first and second

bass. In the outer

movements all six

singers join in

unison with the

choir. In between

there is a regular

sequence of

recitatives and

arias, with one aria

for each of the

characters.

In the magnificent

opening chorus, Bach

lets the winds

‘whirl’ in rapid

triplet figures. The

middle section of

this da capo

movement, however,

is full of charming

echo effects between

the choir and the

instruments. The

plot per se

begins in the first

recitative with an

argument between

Phoebus and Pan, in

which the latter

boasts about his

artistry. By doing

so, however, he

earns the scorn of

Momus, both here and

in the following

aria (third

movement), who calls

out to the show-off:

‘Patron, das macht

der Wind’ (‘My

friend, this is just

hot air’). In the

following recitative

(fourth movement)

Mercury suggests a

contest and asks the

protagonists to

choose their

seconds.

Phoebus begins the

competition with a

beautiful aria

(fifth movement).

The text is full of

the tender longing

with which Phoebus

mourns for his

friend Hyacinth,

killed by Zephyrus

out of jealousy.

Bach put all of his

artistry into this

movement. The

exquisite sonority

of flute, oboe

d’amore and muted

strings is combined

with an expression

of wistful longing.

It ticks all the

boxes: expressive

leaps of a sixth and

seventh in the

opening theme,

sighing grace notes,

caressing triplet

and trill figures.

This movement is a

display of artistic

emotion par

excellence.

Now Pan makes his

appearance. His aria

‘Zu Tanze, zu

Sprunge, so wackelt

das Herz’ (‘Dancing

and leaping sets the

heart in motion’;

seventh movement) is

a rustic passepied,

and forms a striking

contrast to

Phoebus’s aria: it

is earthy and

powerful. Bach makes

the most of the

‘motion’ in musical

terms, making it

thoroughly comical.

In the middle

section of the aria,

where – with a

sidelong glance at

Phoebus – the text

mentions ‘laboured’

music, Bach

introduces

‘laboured’ chromatic

writing. Bach maybe

somewhat biased, but

he is not un fair:

this movement is by

no means lacking in

artistry, and it

comes as no surprise

that Bach reused it

some years later,

with a new text

(‘Dein Wachstum sei

feste’/‘May your

growth be strong’),

in his Peasant

Cantata, BWV

212.

Mercury and Tmolus

are in agreement

(eighth movement):

Phoebus has won, Pan

has lost. Tmolus

strikes up a song of

praise (ninth

movement) for

Phoebus and the

charm of his music.

Bach set this

movement most

charmingly as a trio

with obbligato oboe

d’amore. In the

middle section, to

the words ‘aber wer

die Kunst versteht’

(‘but whosoever

understands the

art’), he pointedly

writes a canon

between the voice

and wind instrument.

Now it is Midas’s

turn to speak (tenth

movement). He

praises Pan, and the

melodiousness and

memorability of his

song – with, unlike

that of Phoebus, was

not ‘gar zu bunt’

(‘all too

colourful’) but

rather ‘leicht und

ungezwungen’

(‘approachable and

unforced’). Midas,

too, strikes up a

song of praise

(eleventh movement).

This time, however,

Bach has tinged the

song with irony:

when Midas refers to

the evidence of his

‘beiden Ohren’ (‘two

ears’ – with a long

note on the syllable

‘oh’), Bach has the

strings bray quietly

like a donkey. In

the following

recitative (twelfth

movement) Midas

receives the

punishment he

deserves: donkey

ears. And there is

more mockery to

follow: in Mercury’s

aria (thirteenth

movement) there is a

mention of a

‘Schellenmütze’

(‘dunce’s cap’) that

the Philistine Midas

has earned.

The final chorus

praises the ‘Kunst

und Anmut’ (‘art and

charm’) of true

music, and defends

it against pedantry

and derision. This

is all part of the

message Bach

intended to convey.

This is even clearer

in the preceding

recitative

(fourteenth

movement), when

Momus tells Midas:

‘Du hast noch mehr

dergleichen Brüder…’

(‘You have brothers

of the same ilk.

Ignorance and

stupidity now wish

to be wisdom’s

neighbours,

judgements are

passed on the spur

of the moment, and

those who so do all

belong in your

society.’) This does

not apply only to

Midas, but also to

critics of Bach and

of his art. And the

ending sounds as if

Bach were trying to

encourage himself:

‘Ergreife, Phoebus,

deine Leier wieder…’

(‘Phoebus, now take

up once more your

lyre, nothing is

more pleasurable

than your songs.’)

We do not know who

or what prompted

Bach in 1729 to wish

to convey such a

message. Later,

though, he had ample

cause to do so – in

1749 for example,

when Johann Gottlieb

Biedermann,

headmaster of the

grammar school in

Freiberg, asserted

that music was the

ruin of youth. This

caused outrage among

musicians and strong

invective, and Bach

could not let it

pass. For a revival

of the cantata that

year he smuggled the

headmaster’s

nickname, Birolius,

and that of one of

his supporters, into

the final lines,

which were changed

to ‘Verdopple,

Phoebus, nun Musik

und Lieder, tobt

gleich Birolius und

ein Hortens

darwider!’

(‘Redouble now,

Phoebus, your music

and songs, though

Birolius and

Hortensius rage

against them!’)

Auf, schmetternde

Töne der muntern

Trompeten, BWV

207a

(Up, Strident

Sounds of Cheerful

Trumpets)

Bach’s parody

technique has

various facets. The

use of existing

material offered him

an opportunity for a

renewed involvement

with the work, and

the chance to

improve and refine

it. A further strong

incentive for Bach

was the possibility

of salvaging for

posterity the

artistic substance

of secular

occasional pieces,

written for a single

performance, by

providing them with

a new religious text

and transforming

them into religious

compositions that

could be reused

every year in the

context of church

services. For Bach

it was very

appealing to take a

work designed for a

single use and bring

it back to life in

this way. And, not

least, the parody

technique offered

practical

advantages: the

composer’s task

could to some extent

be confined to a few

procedures such as

substituting a new

text, plus of course

slight compositional

changes and

additions; and often

the parts for the

original version

could be used again

without extensive

alterations.

The cantata Auf,

schmetternde Töne

der muntern

Trompeten is

an example of the

kind of parody in

which Bach was

clearly primarily

concerned with

practical

considerations. In

this form the

cantata was prepared

for the name day of

the Elector of

Saxony and King of

Poland Augus tus III

on 3rd August 1735.

Bach based it on a

cantata from 1726, Vereinigte

Zwietracht der

wechselnden Saiten

(United Division

of Changing

Strings),

BWV207 [BIS-2001],

written to

congratulate the

Leipzig academic Dr

Gottlieb Kortte on

taking up his law

professorship. Most

of the work in

converting it into

its new version for

the royal name day

fell to the –

unknown –

librettist. It was

his task to imitate

the metre and rhyme

structure of the

1726 cantata text in

a replacement,

parallel text about

the sovereign. Only

in the wording of

the three secco

recitatives (second,

fourth and sixth

movements) did Bach

allow the poet free

rein to write

something

independent of the

earlier version;

movements of this

kind are hard to

parody effectively,

and could in any

case quickly be

composed anew. The

rest of the cantata

– the opening and

closing choruses,

the arias and the

single recitative

with orchestral

accompaniment

(eighth movement) –

received a new text.

At times Bach’s

librettist remained

close to the

original not just

formally but also in

terms of content, as

is shown by a

comparison of the

opening lines. In

both cases the

cantata begins by

calling upon the

participating

instruments to

delight the listener

with their music.

The final chorus of

the 1726 version

started with ‘Kortte

lebe, Kortte blühe!’

(‘Long live Kortte,

may Kortte

flourish!’); in the

new version the

wording is rather

similar: ‘August

lebe, lebe, König!’

(‘Long live

Augustus, may the

King live!).

In the inner

movements the poet

has gone to a lot of

trouble to capture

in verse the virtues

and achievements of

the sovereign and

the alleged

enthusiasm of his

subjects – with the

exaggeration that

was typical of the

period. Although the

reference to the

instruments at the

beginning of the

cantata takes the

existing music into

account, there are

otherwise – as one

might expect –

hardly any

illustrative

allusions. An

exception to this is

the newly composed

tenor recitative

‘Die stille Pleiße

spielt mit ihren

kleinen Wellen’

(‘The calm river

Pleiße plays with

its little waves’;

second movement), in

which Bach imitates

the wave motion of

the river in the

continuo. On the

other hand, some

musical images in

the original piece

have lost their

textural context,

but this seems not

to have bothered

Bach very much. This

applies for example

to the energetic

dotted motif,

repeating a single

note, that the

strings interject in

the otherwise

charming alto aria

with flute ‘Preiset,

späte Folgezeiten’

(‘Praise, later

generations’;

seventh movement).

It has nothing to do

with the new text,

but plenty to do

with the original

one: ‘Ätzet dieses

Angedenken in den

härtsten Marmor

ein!’ (‘Etch this

remembrance into the

hardest marble!’) –

and the string motif

depicts how the

stonemason is

already working on

the marble with his

hammer and chisel.

Clearly Bach just

trusted in the power

of his music.

We should not

neglect to mention

that Bach had

already had recourse

to existing and

established music in

the congratulatory

score of 1726, which

thus returns for a

second time in the

name day cantata.

The opening chorus

is a free

arrangement of the

third movement from

the Brandenburg

Concerto No. 1,

BWV 1046, with the

addition of the

choir and with

trumpets and timpani

instead of horns.

The ritornello that

appears after the

fifth movement also

originates in the

same concerto, where

it was the third

trio of the

concluding minuet.

Bach later added one

more instrumental

piece to the score –

a march that does

not appear in the

original performance

parts. Even if it is

not part of the

cantata, this march

was probably

performed in the

context of the

festivities

surrounding the

sovereign’s name

day.

© Klaus

Hofmann 2016

|

|