|

|

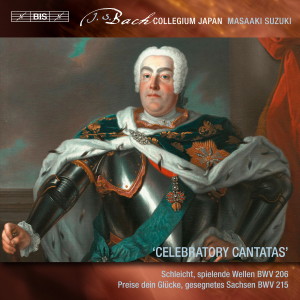

1 CD -

BIS-2231 SACD - (p) 2017

|

|

SECULAR

CANTATAS - Volume 8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dramma per musica |

|

|

|

| "Schleicht,

spielende Wellen, und murmelt

gelinde", BWV 206 |

|

37' 38" |

|

| Tromba I, II, III,

Timpani, Flauto traverse I, II, III,

Oboe I, II, auch Oboe d'amore I, II,

Violino I, II, Viola, Soprano

(Pleiße), Alto (Donau), Tenore (Elbe),

Basso (Weichsel), Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Schleicht, spielende

Wellen, und Murmelt gelinde!... |

6' 10" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): O glückliche

Veränderung!... |

1' 27" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Schleuß des

Janustempels Türen... |

4' 14" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo e Arioso (Tenore): So

recht! beglückter

Weichselstrom!... |

1' 39" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore): Jede Woge meiner

Wellen... |

6' 51" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Alto): Ich nehm

zugleich an deiner Freude teil... |

1' 07" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Alto): Reis von Habsburgs

hohem Stamme... |

5' 46" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Verzeiht,

bemooste Häupter starker Ströme... |

1' 58" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Hört doch! der

sanften Flöten Chor... |

3' 19" |

|

|

| - Recitativo

(Basso, Tenore, Alto, Soprano): Ich

muss, ich will gehorsam sein... |

1' 34" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Die himmlische Vorsicht

der ewigen Güte... |

3' 19" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dramma per musica |

|

|

|

| "Preise

dein Glücke, gesegnetes Sachsen",

BWV 215 |

|

32' 00" |

|

Tromba I, II, III,

Timpani, Flauto traverse I, II, Oboe

I, II (auch Oboe d'amore I, II),

Violino I, II, Viola (auch Violetta),

Soprano I, Alto I, Tenore I, Basso I,

Soprano II, Alto II, Tenore II, Basso

II, Continuo, Fagotto

|

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Preise dein Glücke,

gesegnetes Sachsen... |

7' 35" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Tenore): Wie können

wir, froßmächtigster August... |

1' 12" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore): Freilich trotzt

Augustu's Name... |

7' 03" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): Was hat dich

sonst, Sarmatien, bewogen... |

1' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Rase nur,

verwegner Schwarm... |

3' 40" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Ja, ja!

Gott ist uns noch mit seiner Hülfe

nah... |

1' 21" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Durch die von

Eifer entflammeten Waffen... |

3' 54" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano, Tenore, Basso):

Lass doch, o teurer Landesvater,

zu... |

2' 45" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Stifter der Reiche,

Beherrscher der Kronen... |

2' 23" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hana Blažíková, soprano |

BACH COLLEGIUM

JAPAN / Masaaki Suzuki, Direction

|

|

| Hiroya Aoki,

counter-tenor (BWV 206) |

- Jean-François

Madeuf, Tromba I |

|

| Charles Daniels,

tenor |

- Gilles Rapin, Tromba

II |

|

| Roderick Williams,

bass |

- Hidenori Saito, Tromba

III |

|

|

- Atsushi Sugahara,

Timpani |

|

| Ryo Terakado,

violin |

- Kiyomi Suga, Flauto

traverso I |

|

|

- Liliko Maeda, Flauto

traverso II |

|

| CHORUS |

- Kanae Kikuchi, Flauto

traverso III |

|

Soprano I: Hana Blažíková, Aki Matsui

|

- Masamitsu

San'nomiya, Oboe I, Oboe d'amore I |

|

| Soprano II: Minae

Fujisaki, Eri Sawae |

- Go Arai, Oboe

II, Oboe d'amore II |

|

| Alto I: Hiroya

Aoki, Naoko Fuse |

- Ryo Terakado, Violino

I leader |

|

| Alto II: Tamaki

Suzuki, Chiharu Takahashi |

- Yuko Takeshima, Violino

I |

|

| Tenore I: Charles

Daniels, Yosuke Taniguchi |

- Ayaka Yamauchi, Violino

I |

|

| Tenore II: Yusuke

Fujii, Hiroto Ishikawa |

- Azumi Takada, Violino

II |

|

| Basso I: Roderick

Williams, Chiyuki Urano |

- Yuko Araki, Violino

II |

|

| Basso II: Toru

Kaku, Yusuke Watanabe |

- Shiho Hiromi, Violino

II |

|

|

- Hiroshi Narita, Viola |

|

|

- Ajira Harada, Viola |

|

|

|

|

|

Continuo: |

|

|

- Shuhei Takezawa, Violoncello |

|

|

- Seiji Nishizawa, Violone |

|

|

- Kiyotaka Dosaka, Fagotto |

|

|

- Masato Suzuki, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Saitama

Arts Theater, Concert Hall (Japan)

- February 2016 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer | Engineer |

|

Marion

Schwebel (Take5

Music Production) | Thore

Brinkmann (Take5 Music Production)

| Akimi Hayashi |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BIS -

BIS-2231 SACD - (1 CD) - durata

70' 23" - (p) & (c) 2017 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| COMMENTARY

|

Schleicht,

spielende Wellen

[Glide, Playful

Waves], BWV 206

The ‘dramma per

musica’ Schleicht,

spielende Wellen

is dedicated to

Augustus III

(1696–1763), Elector

of Saxony and King

of Poland. The

history of the work

is linked in a

special way to a

surprise visit the

royal family made to

Leipzig in 1734.

When the royal visit

on 2nd Octo ber 1724

was an nounced, Bach

was working on the

cantata Schleicht,

spielende Wellen,

intended as a

festive piece to

mark the birthday of

Augustus III on 7th

October. But nobody

had con sid ered the

possibility that the

sovereign might be

present in person.

On account of his

visit, a celebratory

event was arranged

for the 5th October,

focusing instead on

the anni versary of

his election as King

of Poland. Bach had

no option but to put

the birthday cantata

aside and devote

himself to the new

project, the cantata

Preise dein

Glücke, gesegnetes

Sachsen, with

all possible haste.

Schleicht, spielende

Wellen eventually

saw the light of day

two years later, on

7th October 1736,

with a festive

performance at the

Café Zimmermann in

Leipzig.

Bach’s unknown

librettist organized

the text as a

roleplay of four

rivers: all of them

have a claim on the

ruler about which

they must come to an

agreement. The

Vistula (bass)

stands for Poland,

the Elbe (tenor) for

Saxony, the Danube

(alto) for Austria

and the Pleiße

(soprano) for

Leipzig. First of

all the four rivers

are called upon to

demonstrate their

festive joy by means

of rushing waves and

strong currents.

After that, each

river has a secco

recitative followed

by an aria. In these

pairs of movements

the Vistula, Elbe

and Danube in turn

have the opportunity

to make their claims

and express their

admiration for the

royal house. Only

the Pleiße puts its

claim forward

silently. It acts as

a mediator, and its

words – ultimately

taken up by all four

rivers – explain

that the Danube

should honour the

royal couple but

also leave them to

the other three

rivers; meanwhile

the Vistula and Elbe

should accept that

the King will share

his time between

Poland and Saxony.

The results of the

encounter are

portrayed in a

recitative from the

four main

characters, who

reach a peaceful

accord and, with

collective

greetings, commend

the King to divine

providence.

With evident purpose

and great skill the

librettist has

delighted in making

abundant use of

river metaphors, and

Bach too avails

himself extensively

of these. No doubt

to the surprise of

all the listeners of

the time, the

splendidly

orchestrated opening

movement begins piano,

then breaking out

all the more

effectively into forte

with timpani and

trumpets. The same

procedure is then

repeated when the

choir enters:

quietly, with a

rocking motion, we

hear the gliding

waves, murmuring

softly in the lower

register,

pianissimo, and then

they rush swiftly

and powerfully,

supported by the

entire orchestra

with fast runs in

the violins, flutes

and oboes.

The Vistula’s

recitative (second

movement) brings our

attention back to

the turmoil of war

in Poland following

the royal election

of 1733, thereupon

praising the King’s

abilities as a

peacemaker all the

more emphatically.

Like the recitative

with its

mythological

allusions, the aria

‘Close the doors of

Janus’s temple’

(third movement) is

evidently intended

for academically

trained listeners.

In ancient Rome the

doors of the Temple

of Janus remained

open whenever the

Empire was at war,

and were closed only

when the war had

been won and peace

reigned on all the

borders. The message

of the aria is thus:

now peace reigns

throughout the land.

As the text

suggests, musical

images of billows

and waves

predominate in the

lively solo violin

part in the aria of

the Elbe. In the

middle section the

voice joins in with

demanding

coloraturas; the

mention of

‘hundredfold echoes’

of the ‘sweet

sounds’ of the

King’s name gives

rise to a wide

variety of echo

effects between the

voice and solo

violin.

The Danube declares

a somewhat indirect

claim on Augustus,

as his wife was an

Austrian princess

from the Habsburg

family (sixth

movement). The aria,

accompanied by two

oboes in a sonorous

and contrapuntally

dense setting, is a

song of praise to

the King’s wife.

The Pleiße now

speaks up as an

arbitrator (eight

movement) – and, in

her aria (ninth

movement),

demonstrates the

harmony that unity

produces: ‘Listen!

The choir of gentle

flutes cheers the

heart, delights the

ear.’ Following the

text, Bach asks for

a ‘choir’ of three

flutes, which

present the

‘agreeable harmony’

of the ‘unbroken

union’ mentioned in

the middle part of

the aria. Such a

musically delicate

flute aria would

never have been

heard before in

Leipzig. In the end

unity and joy reign,

and the choir and

orchestra conclude

the rivers’

confrontation in the

dance-like metre of

a gigue.

Bach’s cantata must

have been very well

liked in Leipzig: in

1740 he performed it

again, with small

adjustments to the

text, to mark the

sovereign’s name day

on 3rd August – this

time in the open

air, in the garden

of the Café

Zimmermann.

Preise dein

Glücke, gesegnetes

Sachsen, BWV 215

[Praise your

Fortune, Blessed

Saxony]

More than any other

secular work by

Bach, the cantata Preise

dein Glücke,

gesegnetes Sachsen

reflects a piece of

history. At the same

time the

circumstances of its

composition provide

insight into Bach’s

sometimes turbulent

everyday

professional life as

Thomaskantor

and director of

music in Leipzig.

The work is a

cantata that pays

tribute to the

Elector of Saxony

and King of Poland,

Augustus III. It

owes its existence

to the surprise

visit made by the

royal family to

Leipzig in 1734 in

order to attend the

annual fair held

around Michaelmas.

The King, Queen and

Princes arrived on

2nd October and, as

the visit had been

announced just three

days previously,

organizing the

essential

congratulatory

celebrations placed

the city elders in a

very difficult

situation. The

city’s students were

inspired – or

perhaps compelled –

to commission a

homage cantata with

all possible haste:

the text from the

well-known man of

letters Magister

Johann Christoph

Clauder (1701–79),

and the music from

Bach. And even if

the librettist

worked very quickly,

Bach cannot have had

more than three days

to produce the

music. The festive

occasion took place

three days after the

King’s arrival, on

5th October. That

day was also the

anniversary of a

significant

political event: the

previous year, in

Warsaw, the Elector

of Saxony had been

elected King of

Poland.

The cantata’s text

frequently refers to

this event, and also

– especially – to

the political

confusion that

resulted from the

monarch’s election.

The text does not,

however, mention

that the election

did not proceed in a

totally orthodox

manner: Augustus did

not put his name

forward until after

the Poles had

already decided in

favour of Prince

Stanisław

Leszczyński, and

then he was elected

King by a minority,

under pressure from

the Habsburgs and

with support from

Russia. Leszczyński,

however, insisted on

his right to the

throne; military

complications

ensued. Leszczyński

and his troops

entrenched

themselves in Danzig

(Gdańsk) and managed

to resist a siege

for some six months

until, in the spring

of 1734, he was

forced to yield to

superior forces and

surrendered.

Magister Clauder

takes a somewhat

different view of

some of these

happenings. In the

fourth movement –

the bass recitative

– he claims that

‘Sarmatia’ (Poland)

chose Augustus

‘above all others’,

especially because

of ‘the magnificence

of his virtue’,

which enraptured all

his subjects.

Anything else stems

from envy and

jealousy! In the

sixth movement, the

soprano recitative,

allusion is made to

an unnamed ‘city

that opposed him for

so long’ and yet

which, as the text

goes on to boast,

‘feel[s] his mercy

more than his

anger’. The city in

question is Danzig.

In the last

recitative, the

eighth movement, the

text takes a swipe

at France: ‘At a

time’, sings the

bass, ‘when we are

surrounded on all

sides by lightning

and noise, yea, when

the might of the

French (which has so

often been quashed)…

even threatens our

fatherland with

sword and fire’ –

and so on. France

was on the opposing

side: Leszczyński

was the

father-in-law of

Louis XV. Later on,

in fact, Poland was

very satisfied with

its King Augustus –

and, overall,

historians have by

no means reached a

negative verdict on

‘the Saxon Piast’ –

as he is called in

the fourth movement.

Bach’s music hardly

requires any

explanation. The

splendid double

chorus with full

orchestra at the

beginning; the rich

use of wind

instruments, also in

recitatives; the

virtuoso solo

writing; the martial

trumpet signal when

the bass sings about

warlike lightning

and noise: Bach knew

what worked! And no

doubt the Leipzig

audience hummed the

beautiful,

hymn-like, rather

effusive ending of

the cantata long

after the event.

Our admiration is

aroused not only by

the beauty of the

music itself but

also by Bach’s rate

of work. In the

shortest imaginable

time he produced

more than forty

pages of score; with

great alacrity the

parts had to be

written out and the

work had to be

rehearsed.

Admittedly Bach had

made the process of

composition easier

in his time-honoured

fashion: for the

opening double

chorus he reused the

beginning of a

cantata from 1732,

written for the name

day of Augustus the

Strong (Es lebe

der König, der

Vater im Lande,

BWV Anh. 11 – of

which only the text

has survived). A

decade and a half

later, Bach revised

this movement again;

in that form, as the

Osanna in

excelsis of

the Mass in B minor,

it acquired a

longevity and

relevance that went

far beyond its own

time.

In the arias for

tenor (third

movement) and bass

(fifth movement),

too, Bach evidently

drew on existing

works – although

these cannot be

identified with

certainty. The only

parts to have been

composed completely

from scratch were

the recitatives, the

soprano aria

(seventh movement)

and the final

chorus. The soprano

aria is a display

piece with subtle,

chamber-music-like

sonority. Two

transverse flutes in

unison interact with

the soprano

(supported by oboe

d’amore) above a

bass line that is an

octave higher than

usual, played by

violins and violas

without any continuo

accompaniment. Such

a sound image, so to

speak stripped of

all earthly burden,

is used by Bach

primarily for

depicting purity and

innocence. Here it

characterizes the

King’s nobility:

‘But to repay evil

with charity is the

pre rogative… of

Augustus’. Bach

enthusiasts will

recognize the music:

it appears in

modified form in

Part 5 of the Christmas

Oratorio as a

bass aria with the

text ‘Erleucht auch

meine finstre

Sinnen’ (BWV248/47).

Bach’s ‘dramma per

Musica’ was

presented as an

evening

entertainment in the

open air, in front

of the King’s

lodgings in the

Apelsches Haus

(nowadays

Königshaus) on the

south side of the

market square in

Leipzig. The Leipzig

municipal chronicles

tell of a festive

procession of

musicians,

accompanied by 600

students, each

bearing a wax torch.

The music was a

total success; the

chronicle reports

that ‘His Royal

Majesty, alongside

his Royal Spouse and

Royal Princes… did

not leave the window

before the music was

ended, but listened

to it graciously,

and His Majesty

liked it extremely

much’.

© Klaus

Hofmann 2016

|

|