|

|

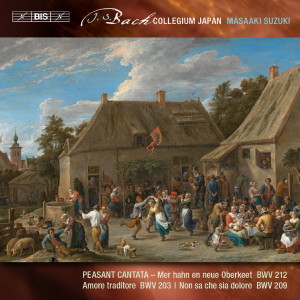

1 CD -

BIS-2191 SACD - (p) 2016

|

|

SECULAR

CANTATAS - Volume 7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cantate burlesque |

|

|

|

| "Mer hahn en neue

Oberkeet", BWV 212 |

|

29' 14" |

|

Corno, Flauto

traverso, Violino I, II, Viola,

Soprano, Basso, Continuo, Cembalo

|

|

|

|

| -

[Ouverture] |

2' 05"

|

|

|

| -

Aria. Duetto (Soprano, Basso): Mer

hahn en neue Oberkeet... |

0' 35" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso, Soprano): Nu,

Mieke, gib dein Guschel immer

her... |

0' 56" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Ach, es schmeckt

doch gar zu gut... |

0' 54" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): Der Herr ist

gut: Allein der Schösser... |

0' 24" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Ach, Herr

Schösser, geht nicht gar zu

schlimm... |

1' 12" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Es bleibt

dabei... |

0' 18" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Unser

trefflicher... |

1' 57" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso, Soprano): Er

hilft uns allen, alt und jung... |

0' 27" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Das ist

galant... |

1' 08" |

|

|

| - Recitativo

(Basso): Und unsre gnädge

Frau... |

0' 42" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Fünfzig Taler

bares Geld... |

0' 57" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Im Enst

ein Wort!... |

0' 23" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Klein-Zschocher

müsse... |

7' 19" |

|

|

| - Recitativo

(Basso): Das ist zu klug vor

dich... |

0' 24" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Es nehme

zehntausend Dukaten... |

0' 45" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Das klingt

zu liederlich... |

0' 19" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Gib, Schöne... |

0' 30" |

|

|

| - Recitativo

(Basso): Du hast wohl recht... |

0' 16" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Dein Wachstum sei

feste und lache vor Lust!... |

5' 09" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano, Basso): Und

damit sei es auch genung... |

0' 16" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Und dass ihr's

alle wisst... |

0' 36" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso, Soprano): Mein

Schatz, erraten!... |

0' 29" |

|

|

| -

Chor (Soprano, Basso): Wir gehn

nun, wo der Dudelsack... |

1' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "Non

sa che sia dolore", BWV 209 |

|

21' 35" |

|

| Flauto traverso,

Violino I, II, Viola, Soprano,

Continuo |

|

|

|

| - Sinfonia |

5' 49" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Non sa che

sia dolore... |

0' 53" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Parti pur e con

dolore... |

9' 20" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Tuo saver

al tempo e l'età contrasta... |

0' 26" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Ricetti gramezza

e pavento... |

5' 03" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "Amore

traditore", BWV 203 |

|

11' 57" |

|

| Basso solo, Cembalo

obbligato |

|

|

|

| -

[Aria] (Basso): Amore

traditore... |

5' 29" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): Voglio

provar... |

0' 42" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Chi in amore ha

nemica la sorte... |

5' 43" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mojca Erdmann, soprano |

BACH COLLEGIUM

JAPAN / Masaaki Suzuki, Direction

|

|

| Dominik Wörner,

bass |

- Nobuaki Fukukawa,

Corno |

|

|

- Kiyomi Suga, Flauto

traverso |

|

| Kiyomi Suga,

flauto traverso |

- Natsumi Wakamatsu,

Violino I leader |

|

| Nobuaki Fukukawa,

corno |

- Shiho Hiromi, Violino

I* |

|

|

- Ayaka Yamauchi, Violino

I |

|

|

- Azumi Takada, Violino

II |

|

|

- Yuko Araki, Violino

II |

|

|

- Hiroshi Narita, Viola |

|

|

- Akira Harada, Viola |

|

|

- Yuko Takeshima, Viola** |

|

|

|

|

|

Continuo: |

|

|

- Shuhei Takezawa, Violoncello |

|

|

- Toru Yamamoto, Violoncello |

|

|

- Seiji Nishizawa, Violone

|

|

| * BWV 209 Violino II |

- Masaaki Suzuki, Cembalo

& Organo

|

|

| ** BWV 209 Violino I

|

- Masato Suzuki, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hakuju

Hall, Tokyo (Japan) - September

2015 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer | Engineer |

|

Jens

Braun (Take5 Music

Production) | Fabian

Frank | Akimi Hayashi |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BIS -

BIS-2191 SACD - (1 CD) - durata

63' 25" - (p) & (c) 2016 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| COMMENTARY

|

Mer

hahn en neue

Oberkeet (Peasant

Cantata), BWV 212

(We have a

new governor)

Among Bach’s secular

cantatas, two works

have long enjoyed

particular

popularity: the

socalled ‘Coffee

Cantata’ Schweigt

stille, plaudert

nicht (BWV211)

and the ‘Peasant

Cantata’ Mer

hahn en neue

Oberkeet (We

have a new

governor). In

both works Bach

displays his ‘folk’

side. The Coffee

Cantata presented a

humorous version of

an argument within a

bourgeois family of

the period. In the

Peasant Cantata,

however, Bach

transports his

listeners into a

farming environment.

The action is set at

the manor of

Klein-Zschocher,

south-west of

Leipzig. Here, on

30th August 1742,

the cantata was

performed in

connection with the

accession to the

estate of the

nobleman Carl

Heinrich von Dieskau

(1706–82). Dieskau

had inherited the

estate in the spring

of 1742, and on 30th

August that year

Klein-Zschocher

celebrated the

customary hereditary

homage. This was

also the 36th

birthday of the new

lord of the manor.

There were therefore

twice as many

reasons to

celebrate.

The libretto is by

Bach’s regular

Leipzig

collaborator,

Christian Friedrich

Henrici (1700–64),

who as an author

went by the name of

Picander although in

fact he was a tax

officer and local

tax collector by

profession. Dieskau

was ‘Kreis

hauptmann’ (regional

governor) and, as

head of the tax

authority, Henrici’s

boss. The cantata

may, therefore, have

been written at

Henrici/Picander’s

instigation.

Picander’s libretto

is based on

exchanges between a

peasant couple. The

plot is simple: it

all starts with a

scene from the

homage festivities,

at which the peasant

girl Mieke and a

young farmer,

enlivened by the

free beer, flirt

with each other.

Picander skilfully

uses the Upper Saxon

dialect as a means

of depicting the

milieu. This also

means that the

slightly coarse

aspect of the

couple’s exchanges

is toned down, and

the lewd references

to the guests and

the ‘Kammerherr’

(Chamberlain)

himself into which

Mieke and her

admirer soon descend

are perceived as

merry and ironical.

For example the

local priest is

mentioned,

reportedly scowling

at the joyful

goings-on (second

movement). Even

Dieskau himself is

not spared: ‘Er weiß

so gut als wir und

auch wohl besser,

wie schön ein

bisschen Dahlen

schmeckt’ (‘He knows

as well as we do,

indeed better, how

fine a little

smooching tastes’ –

move ment 3) – an

allusion that

possibly did not

please Dieskau’s

‘noble Lady’. She

herself is later

praised: she is

‘nicht ein prinkel

stolz’ (‘not the

slightest bit

proud’), ‘recht

fromm, recht

wirtlich und genau’

(‘very pious,

hospitable and

proper’) and so

thrifty that she can

turn a ‘Fledermaus’

(a small coin) into

four thalers

(movement 11). Later

the hope is

expressed that the

‘Schöne’ (‘fair

lady’) may have

‘viel Söhne’ (‘many

sons’; movement 18)

– a wish that is not

entirely free of

irony, as the

Dieskaus had

hitherto had only

daugh ters, five in

all.

In addition there

are all sorts of

references to

regional politics

and tax collection.

It was to Dieskau’s

credit that in the

most recent

‘Werbung’

(‘recruitment’)

Klein-Zschocher had

escaped lightly

(movement 9), and

that the

neighbouring

villages of

Knauthain and

Cospuden, which also

belonged to the

estate, were spared

the ‘caducken

Schocken’ (‘extra

land-dues’, i.e. the

property tax for

fallow land;

movement 10). In

movement 5 a

‘Schösser’ (a tax

collector and

official), who is

evidently a guest at

the festivities,

gets what is coming

to him on account of

the imposition of a

‘neu Schock’ (‘new

tax’: two and a half

thalers) ‘wenn man

den Finger kaum ins

kalte Wasser steckt’

(‘before we’ve

hardly got our

fingers wet’, i.e.

by fishing without

authorization).

Later a certain

‘Herr Ludwig’ and an

accountant are

mentioned, who on

this occasion –

clearly contrary to

their usual practice

– are forced to

visit the tavern

together with the

peasants (movement

23).

There is no

parsimony with

positive words about

their lords and

masters. Mieke sets

about singing ‘der

Obrigkeit zu Ehren

ein neues Liedchen’

(‘in honour of our

rulers, a new song’;

movement 13) and

performs a charming

aria expressing good

wishes for

Klein-Zschocher

(movement 14). But

her friend remarks

disparagingly that

it is just a song

‘nach der Städter

Weise’ (‘like they

sing in town’); ‘wir

Bauern singen nicht

so leise’ (‘We

peasants don’t sing

so gently’; movement

15), and immediately

strikes up a bois

terous song in his

own coarse style, in

which he wishes the

Chamberlain ten

thousand ducats and

a good glass of wine

every day (movement

16). Now it is

Mieke’s turn to

criti cize him when

she also launches

ironically into a

peasant-style song

(move ment 18). The

farmer then decides

‘auch was

Städtisches zu

singen’ (‘to sing

something in the

town style too’): a

song full of good

wishes for growth

and prosperity

(movement 20). This

little stylistic

dispute – ‘urban’

versus ‘peasant’

music – brings the

action to an end:

every one goes to

the tavern, where

the bagpipes are

already droning, and

gives three cheers

for Dieskau and his

family (movement

24).

In Bach’s music we

can plainly hear his

enjoyment of how the

scene is described

in the libretto.

With a small basic

complement of two

violins (mostly

playing in unison),

one viola and

continuo, Bach may

have had typical

village music in

mind; in passing

these instruments

are joined by a

flute (movement 14)

and hunting horn

(movements 16 and

18). The folk style

already

characterizes the

instrumental intro

duction, a

‘patchwork overture’

in which we hear a

sequence of quite

disparate sections,

in the manner of a

potpourri. From time

to time Bach quotes

folk songs: in

movement 3, as the

peasant couple is

flirting, there is

an instru mental

reference to ‘Mit

mir und dir ins

Federbett, mit mir

und dir ins Stroh’

(‘With thee and me

in the featherbed,

with thee and me in

the hay’) or in the

‘ducat aria’

(movement 16), which

alludes to the

popular tune ‘Was

helfen mir tausend

Dukaten, wenn sie

versoffen sind’

(‘What good are a

thousand ducats to

me if they are all

drunk away’). Bach

also strikes a folk

note in the two

duets at the

beginning and end of

his ‘Cantate bur

lesque’ and, like

the overture, the

arias also contain

the rhythms of

dances that were

popular at the time

such as the

polonaise (movement

4), sarabande

(movement 8, quoting

the famous ‘Follia’

melody), mazurka

(movement 12) and

minuet (movement

14). Bach quotes

himself in the

‘urban’ bass aria

‘Dein Wachs tum sei

feste’ (‘May your

growth be strong’;

movement 20): it is

a parody of Pan’s

aria ‘Zu Tanze, zu

Sprunge, so wackelt

das Herz’ (‘In

dancing and leaping

my heart shakes’

from the cantata Geschwinde,

ihr wirbelnden

Winde (Swift,

you swirling winds,

BWV 201). Probably

the similarly

‘urban’ soprano aria

‘Klein-Zschocher

müsse so zart und

süße’

(‘Klein-Zschocher

should be as tender

and sweet’; movement

14) is also derived

from an earlier

work.

In addition we know

that the festivities

in Klein-Zschocher

ended with a

firework display.

And apparently there

was more music, too:

according to the

musicologist Hugo

Riemann (1849–1919),

a now lost trio

sonata by Johann

Gottlieb Graun

(1702/03–71) bore

the date ‘30th

August 1742’ in

Bach’s handwriting.

Non sa che sia

dolore (He does

not know what

sorrow is), BWV

209

The texts of Bach’s

secular cantatas,

like those of his

sacred cantatas, are

usually in German.

The two surviving

Italian cantatas

associated with his

name – Non sa

che sia dolore

and Amore

traditore –

are striking

exceptions, and have

long been regarded

with scepticism by

Bach biographers and

researchers. As both

of the cantatas have

only survived as

copies, we do not

have documentary

verification of

Bach’s authorship.

Moreover, stylistic

considerations

should be taken into

account. The two

pieces, however, are

very different

cases, and

researchers have

thus approached them

with varying levels

of interest.

The problem of Non

sa che sia dolore

has been occupying

Bach researchers for

a good hundred

years, although they

have so far failed

to provide

definitive

clarification

concerning its

authenticity and the

circumstances of its

composition. A

particular incentive

for examining this

work is provided by

the text –which is

by no means an

unproblematic one.

Although its meaning

is partly obscured

by poetic images and

allusions, it

nevertheless allows

the outline of the

work’s motivation

and purpose to

emerge: the cantata

is a farewell to a

young scholar who is

in the process of

taking leave of his

existing life and

friends, and who can

count on finding

important patrons

when he reaches the

end of his journey,

in Ansbach in

Franconia.

Who might this young

scholar have been?

One of the more

recent hypotheses

has suggested Lorenz

Christoph Mizler

(1709–78), founder

of the ‘Sozietät der

musikalischen

Wissenschaften‘

(‘Corresponding

Society of the

Musical Sciences’)

that is often

associated with his

name – and of which

Bach became a member

in 1747. Mizler came

from near Ansbach,

and had studied in

Leipzig where he

became a pupil of

Bach’s. When he took

his Master’s degree

in 1734, he

dedicated his

dissertation

(published the same

year) to four

prominent musical

figures, one of whom

was Bach. After that

he left Leipzig, and

his departure might

have provided the

impulse for the

cantata. Many

details of the text

and also the

prominent role

played by the

transverse flute in

the cantata would be

suitable for Mizler,

who was himself an

enthusiastic

flautist.

And who could have

written the

cantata’s text?

Several linguistic

details reveal that

the author was not

Italian but German,

and that writing the

text caused him some

problems. For

assistance he helped

himself liberally to

Italian literature:

he turned in the

introductory verses

to the classical

poet Giovanni

Battista Guarini

(1538–1612) and in

the rest of the work

to the opera

librettist Pietro

Metastasio

(1698–1782). He

evidently had a

thorough literary

education. Here,

too, the evidence

seems to point in

one direction: to

Johann Matthias

Gesner (1691–1761),

then headmaster of

the Thomasschule in

Leipzig who, when he

had been headmaster

of the grammar

school in Ansbach in

1729–30, had already

become aware of

Mizler, and had

become his mentor

and patron.

Admittedly, all of

these are no more

than hypotheses,

speculative attempts

to assign the

cantata a place in

Bach’s life and

personal

environment, on the

basis of its text.

But the music, too,

is difficult to

categorize. In terms

of format, a solo

soprano cantata with

an opening concertante

movement for flute

and two da capo

arias introduced by

recitatives is by no

means unusual. It is

also unproblematic

to believe that Bach

was the composer of

the sinfonia and

recitatives. What is

surprising, however,

is the relative

modernity of the

arias, which prove

to be strongly

influences by the

stylistic world of

Italian opera and

can tata writing.

But perhaps the

music’s Italianità

can be understood as

a wholly inten

tional correlation

with the Italian

text.

Despite all the

efforts of Bach

scholars, Non sa che

sia dolore has

remained an enigma. Perhaps

one day a fortunate

source discovery

will shed further

light on the matter.

Until then, however,

the music can

captivate its

audiences and, with

its beauty tinged

with mys tery, lead

them into the world

of fantasies.

Amore traditore

(Treacherous

love), BWV 203

This short solo

cantata for bass and

harpsichord,

comprising just

three movements, has

survived in a

composite manuscript

from the eighteenth

century, which was

still available when

the

Bach-Gesellschaft’s

complete edition was

prepared in 1862 but

has subsequently

disappeared. In that

manuscript the

cantata was

definitively

labelled as a work

‘di Giov. Seb.

Bach’. Nonetheless,

doubts as to its

authenticity are

legitimate. These

have nothing to do

with the quality of

the music. It is a

very typical Italian

chamber cantata, and

its text is equally

typical: the

monologue of a

disappointed lover,

who takes Amor, the

god of love, to

task, accuses him of

betrayal and

deception, and

defiantly refuses to

be a suffering slave

to unrequited love.

The form of the

cantata follows an

established pattern:

two da capo arias

are linked by a

recitative. The

first aria has as

its basis a basso

continuo ritornello,

which frames and

subdivides the

movement. Above its

ostinato motifs the

vocal line roams

freely, sometimes

alluding to them by

means of imitation.

A special feature of

the second aria is

that the harpsichord

is used not as a

continuo instrument

with a chordal

accompaniment (as it

had been previously)

but in a virtuoso, concertante

role. Here the

musical activity

takes place on two

almost totally

separate levels. The

singer presents

something akin to a

vocal minuet, at a

moderate tempo and

with a relatively

simple metrical

scheme, without

extended

coloraturas,

progressing to a

large extent in two-

and four-bar groups

typical of dance

music. In sharp

contrast, however,

the harpsichord

plays an extremely

lively part with

toccata-like

figurations and, at

times, full chords.

This is the work of

a very idiosyncratic

composer.

If the cantata had

not already been

linked to the name

of Bach, nobody

would have thought

of ascribing it to

him. Stylistically

it does not really

fit anywhere in his

output. One might at

best imagine that

his link to the

piece was as an

arranger rather than

a com poser. Perhaps

the cantata was

originally for

another, higher

vocal range, and was

arranged for bass

voice at a later

stage, possibly by

Bach. Or perhaps the

concertante

harpsichord part was

added by an arranger

in place of a

normal, chordal

continuo part –

again Bach might

have done so. This

cantata, too,

presents us with

many riddles.

© Klaus

Hofmann 2016

|

|