|

|

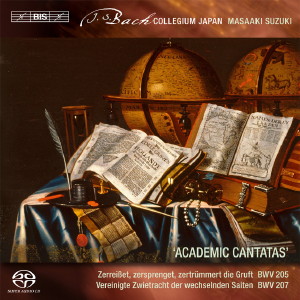

1 CD -

BIS-2001 SACD - (p) 2014

|

|

SECULAR

CANTATAS - Volume 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Der zufriedengestellte Äolus

- Dramma per musica |

|

|

|

| "Zerreißet,

zersprenget, zertrümmert die

Gruft", BWV 205 |

|

39' 00" |

|

| Tromba I, II, III,

Timpani, Corno I, II, Flauto traverso

I, II, Oboe I auch Oboe d'amore, Oboe

II, Violino I, II, Viola, Viola

d'amore, Viola da gamba, Soprano

(Pallas), Alto (Pomona), Tenore

(Zephyrus), Basso (Äolus), Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

[Chorus]: Zerreißet,

zersprenget, zertrümmert die

Gruft... |

5' 58"

|

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): Ja! ja! Die

Stunden sind nunmehro nah... |

1' 37" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Wie will ich

lustig lachen... |

4' 04" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Tenore): Gefürcht'ter

Äolus... |

0' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore): Frische Schatten,

meine Freude... |

4' 05" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso): Beinahe

wirst du mich bewegen... |

0' 35" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Alto): Können nicht die

roten Wangen... |

3' 42" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Alto, Soprano): So

willst du, grimmger Äolus... |

0' 44" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Soprano): Angenehmer

Zephyrus... |

3' 30" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano, Basso): Mein

Äolus... |

2' 14" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Basso): Zurücke, zurücke,

geflügelten Winde... |

3' 30" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano, Alto, Tenore):

Was Lust!... |

1' 28" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Alto, Tenore): Zweig und

Äste... |

2' 49" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Soprano): Ja, ja!

ich lad euch selbst zu dieser

Feier ein... |

0' 39" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Vivat August, August

vivat... |

3' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dramma per musica |

|

|

|

| "Vereinigte

Zwietracht der wechselnden

Saiten", BWV 207 |

|

33' 16" |

|

| Tromna I, II, III,

Timpani, Flauto traverso I, II, Oboe

[d'amore] I, II, Taille, Violino I,

II, Viola, Soprano (Glück), Alto

(Dankbarkeit), Tenore (Fleiß), Basso

(Ehre), Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Vereinigte Zwietracht

der wechselnden Saiten... |

4' 38" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Tenore): Wen treibt

ein edler Trieb zu dem, was Ehre

heißt... |

1' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Tenore): Zieht euren Fuß

nur nicht zurücke... |

3' 50" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Basso, Soprano): Dem

nur allein... |

2' 00" |

|

|

| -

Aria Duetto (Basso, Soprano): Den

soll mein Lorbeer... |

4' 52" |

|

|

| -

Ritornello |

1' 08" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Alto): Es ist kein

leeres Wort... |

1' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Alto): Ätzet dieses

Angedenken... |

5' 19" |

|

|

| -

Recitativo (Tenore, Basso, Soprano,

Alto): Ihr Schläfrigen,

herbei... |

2' 54" |

|

|

| -

Anhang: Marche |

1' 15" |

|

|

| -

[Chorus]: Kortte lebe, Kortte

blühe... |

3' 35" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joanne Lunn, soprano

(Pallas, Glück)

|

BACH COLLEGIUM

JAPAN / Masaaki Suzuki, Direction

|

|

| Robin Blaze,

counter-tenor (Pomona, Dankbarkeit) |

- Jean-François

Madeuf, Tromba I |

|

Wolfram Lattke,

tenor (Zephyrus, Fleiß)

|

- Joël Lahens, Tromba

II, Corno II

|

|

Roderick Williams,

baritone (Äolus, Ehre)

|

- Hidenori Saito, Tromba

III |

|

|

- Lionel Renoux, Corno

I |

|

| Kiyomi Suga,

flauto traverso |

- Thomas Holzinger,

Timpani |

|

| Kanae Kikuchi,

flauto traverso |

- Kiyomi Suga, Flauto

traverso I |

|

| Masamitsu

San'nomiya, oboe d'amore |

- Kanae Kikuchi, Flauto

traverso II |

|

| Natsumi Wakamatsu,

viola d'amore & violin |

- Masamitsu

San'nomiya, Oboe I / Oboe d'amore I

|

|

| Masako Hirao,

viola da gamba |

- Harumi Hoshi, Oboe

II / Oboe d'amore II |

|

|

- Atsuko Ozaki, Taille |

|

| CHORUS |

- Natsumi Wakamatsu,

Violino I leader |

|

| Soprano: |

- Yuko Takeshima, Violino

I |

|

Joanne Lunn,

Yoshie Hida, Aki Matsui, Eri Sawae

|

- Ayaka Yamauchi, Violino

I |

|

| Alto: |

- Azumi Takada, Violino

II |

|

| Robin Blaze,

Hiroya Aoki, Toshiharu Nakajima, Tamaki

Suzuki |

- Yuko Araki, Violino

II |

|

| Tenore: |

- Shiho Hiromi, Violino

II |

|

| Wolfram Lattke,

Yusuke Fujii, Takayuki Kagami, Yosuke

Taniguchi |

- Mika Akiha, Viola |

|

| Basso: |

- Akira Harada, Viola |

|

| Roderick Williams,

Toru Kaku, Chiyuki Urano, Yusuke Watanabe |

- Natsumi Wakamatsu,

Viola d'amore |

|

|

Continuo: |

|

|

- Hidemi Suzuki, Violoncello |

|

|

- Masako Hirao, Viola

da gamba |

|

|

- Seiji Nishizawa, Violone |

|

|

- Yukiko Murakami, Bassono |

|

|

- Masato Suzuki, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

MS&AD

Shirakawa Hall, Nagoya (Japan) -

July 2013

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer | Engineer |

|

Marion

Schwebel (Take5 Music Productions)

| Thore Brinkmann (Take5 Music

Productions) | Akimi Hayashi |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BIS -

BIS-2001 SACD - (1 CD) - durata

73' 06" - (p) & (c) 2014 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| COMMENTARY

|

Introduction

This recording

explores the

modestly

proportioned genre

of secular cantatas

by Johann Sebastian

Bach. Nowadays this

group of works,

which suffers more

than most from the

loss of many of its

members, contains

only slightly more

than twenty

completely preserved

cantatas. In

addition there are a

dozen or so cantata

texts that Bach set

but for which the

music itself has not

survived. In total

we know of around

fifty secular

cantatas that Bach

composed; in fact,

however, their

number must have

been significantly

larger.

Most if not all of

Bach’s secular

cantatas were

envisaged as

occasional pieces,

their text and music

written to order, in

exchange for a fee,

and intended for

specific occasions

of widely varying

character. They

included festive and

congratulatory music

for court, political

tributes (for

instance to the

Prince of Saxony and

his relatives) and

also works for

celebrations among

Leipzig’s

bourgeoisie or

academia.

Among the various

literary forms used

in secular cantatas,

Bach accorded

particular

significance to the

so-called ‘dramma

per musica’. In such

works the libretto

is constructed

dramatically, i.e.

the cantata has a

plot, and the

singers embody

various roles. The

proximity of opera

is unmistakable,

although the ‘drammi

per musica’ do

without the scenic

element, confining

themselves to verbal

interaction.

The libretti of

these ‘dramatic’

cantatas are often

based on

mythological stories

from antiquity, as

told by Latin

Classical poets such

as Virgil (70–19

B.C.) or Ovid (43–18

B.C.). It was common

to juxtapose the

gods, demigods and

other characters

from this world of

legend with freely

invented allegorical

figures –

personifications of

ideas that embody

specific human

characteristics or

of abstract concepts

such as time or

fate. The ‘dramma

per musica’ was

especially

widespread in the

lofty realms of

princely tribute and

academic festivity:

educated people were

familiar with these

literary traditions.

And by delegating

the unavoidable

flattery to

literary, fictional

figures, it became

easier for all

involved not to take

things too

literally. The two

works on this

recording exemplify

this type of

dramatic cantata.

Zerreißet,

zersprenget,

zertrümmert die

Gruft, BWV 205

Tear Asunder,

Smash, Lay Waste

to the Vault

The cantata with the

subtitle ‘Aeolus

Appeased’ was

written for the name

day of the Leipzig

academic and later

university professor

Dr August Friedrich

Müller (1684–1761)

on 3rd August 1725,

and was probably

commissioned by the

student body. Müller

taught law and

philosophy at the

university and

enjoyed exceptional

popularity among his

stud ents. It

appears that some

special event in his

academic career was

celebrated together

with his name day in

1725, but we have no

details of what that

event might have

been. The cantata

text is by the

Leipzig poet

Christian Friedrich

Henrici, also known

as Picander

(1700–64), who

shortly after wards

would begin a closer

collaboration with

Bach. One could well

imagine the

performance taking

place outdoors

during the evening,

perhaps accompanied

by a torchlight pro

cession of students.

The summer weather

that would have been

desirable for such

an occasion is also

– indirectly – the

subject of the

cantata’s dramatic

happenings. First of

all it takes us back

to the world of

antiquity and

legend, to the

Mediterranean, to

the islands near

Sicily, to Aeolia.

There – according to

Virgil’s Aeneid

– Aeolus, the King

of the Winds, holds

the mighty autumn

storms captive,

letting them loose

on the world at the

appointed time. In

the opening chorus

they are already

raging, stirring

each other up, ready

to break free from

their prison, burst

out and overcome the

air, water and earth

with their havoc.

Aeolus appears and

announces that,

‘after summer has

soon ended’, he will

release his ‘loyal

subjects’, and give

them free rein to

cause chaos. Aeolus,

himself rather

churlish, is al

ready looking

forward to the time

‘when everything

becomes disordered’

(third movement).

Then, however,

supplicants of all

kinds make an

appearance:

Zephyrus, the soft

west wind and god of

mild summer breezes,

asks Aeolus for

compassion and

invokes memories of

idyllic summer

evenings in the open

air – without,

however, fully

managing to convince

the King of the

Winds (movements

4–6). Pomona too,

goddess of fruitful

abundance, attempts

in vain to win over

Aeolus. Finally

Pallas Athene, god

dess of wisdom and

the arts, succeeds

in making Aeolus

relent, requesting

that Zephyrus alone

should attend the

feast ‘upon my

hilltops’ (i.e. on

Mount Helicon, home

of the Muses), and

that no other wind

should disrupt the

celebrations in

honour of the famous

scholar August

Müller (movements

7–10).

Aeolus then summons

the winds to return

and to blow more

gently, to the

delight of Pomona,

Zephyrus and Pallas,

who immediately turn

their attention to

preparations for the

feast (movements

11–13). Pallas

invites everybody to

the celebration

(movement 14) and

finally there is a

vivat for August

Müller.

Wealthy patrons seem

to have played a

part in the work’s

origin, as Bach’s

festive orchestra is

un usually lavishly

proportioned. In

addition to the

standard complement

of strings and

continuo, two flutes

and two oboes, he

calls for three

trumpets and timpani

as well as two horns

– not to mention the

viola d’amore, viola

da gamba and oboe

d’amore, all of

which are featured

as solo instruments

in the arias. Bach

could hardly have

wished for a more

colourful orchestra.

The libretto, too,

left nothing to be

desired, giving Bach

the opportunity to

frame the entire

piece with two

splendid choral

movements and to

portray a very wide

range of emotions in

a series of musical

images – from the

raging of the wind

at the beginning to

the mellow lament of

Zephyrus (fifth

movement). It also

provided plenty of

opportunities to

illustrate the

events by means of

numerous musical

details.

In this work Bach

writes one display

piece after an

other. The opening

chorus is a colossal

portrayal of the

powerfully raging

winds, angrily

rattling their

prison gate. These

are depicted

musically by wild

rising and falling

scales, in the same

and opposite

directions, a

turmoil into which

the choir injects

lively coloraturas

and shouts of ‘tear

asunder’. At the

same time this

movement, from a

purely musical point

of view, is a

skilfully written

polychoral concerto

in which the various

groups of musicians

are effectively

contrasted. Right at

the outset the

trumpets, strings

and horns, in lively

alternation, play

the motif that is

later associated

with the words ‘tear

asunder’ in the

choir, while the

flutes strike up the

scale motif and

immediately pass it

on to the oboes, who

in turn relay it to

the strings. The

interplay of the

various groups of

performers, in con

stantly changing

combinations of

motifs and colours,

dominates the entire

movement.

The second movement,

a recitative in

which Aeolus

addresses the winds,

is vividly

illustrated by the

orchestra. Almost

untameable, the

winds constantly

rise up in protest;

every time there is

a pause in the King

of the Winds’

speech, they make

themselves heard

vociferously. The

following aria, ‘How

I shall laugh

merrily’, depicts

Aeolus as a ruffian,

looking forward to

the chaos that the

storms will cause.

His laughter is

heard in striking

coloraturas, and the

string orchestra

portrays the general

confusion.

Then, however,

Zephyrus’s

recitative (fourth

movement) shifts the

musical emphasis:

the roaring of the

winds and the

blustering of the

King of the Winds

yield to the quieter

tones of the

supplicant. Now we

hear chamber music

of a most exquisite

kind. Quiet

instruments – viola

d’amore and viola da

gamba – accompany

Zephyrus’s gentle

lament (fifth

movement). The oboe

d’amore, the

personification of

sweetness, supports

Pomona’s attempt to

soften the King of

the Winds (seventh

movement). And in

Pal las’s aria

(ninth movement),

Bach uses a solo

violin to illustrate

the wish that the

‘pleasant Zephyrus’

might, with his

gently breeze, fan

the summit of

Helicon; the

charming solo line

explores the

instrument’s very

highest register.

In the dialogue

between Pallas and

Aeolus (tenth

movement), the

turning point of the

action, Bach can not

resist surrounding

the name of the

learned Dr August

Müller with a halo

of flute sound. The

taming of the winds

in Aeolus’s aria

(eleventh movement)

is presented by Bach

in a musical costume

that is without

equal: it is

accompanied only by

continuo, trumpets,

timpani and horns.

Such an exquisite

piece for wind

instruments had

surely never before

been heard in

Leipzig.

At the end, nothing

but joy prevails

among the successful

supplicants. The

finale is a merry

march in a concise

rondo form,

dominated by calls

of ‘Vivat’. One can

almost see the

assembled party

raising their

glasses and drinking

the health of the

learned professor –

and the instruments,

too, constantly add

their own ‘vivat’

motif to the festive

mayhem.

Vereinigte

Zwietracht der

wechselnden Saiten,

BWV 207 United

Division of

Changing Strings

This cantata, too,

takes us into the

ambit of Leipzig

University. It was

composed for the

jurist Dr Gottlieb

Kortte (1698−1731).

The occasion was

Kortte’s appointment

as a professor

extraordinarius. The

festive performance

probably took place

on 11th December

1726, the day on

which Kortte gave

his inaugural

address – from

memory, as

absent-mindedly he

had left his

manuscript at home.

Kortte had just

celebrated his 28th

birthday – hardly

older than his

students – and he

enjoyed particular

popularity among the

young academics. The

instigators of the

cantata performance

were probably to be

found among his

students. Even the

text may have been

written by one of

his students, namely

Heinrich Gottlieb

Schellhafer

(1707−57), later a

professor of law in

his own right, who

in his later years

also wrote texts for

works by Telemann.

As was popular at

the time, the text

of this

congratulatory

cantata is placed in

the mouths of four

allegorical

characters, and in

Bach’s music these

are distributed

between the four

vocal registers. The

characters represent

four academic

virtues: Happiness

(soprano), Gratitude

(alto), Diligence

(tenor) and Honour

(bass). Bearing this

distribution of

roles in mind, it is

by no means

difficult to follow

the events in the

cantata. According

to the opening

chorus, the cantata

is all about saying

‘with your exultant

notes… what is the

reward of virtue

here’. First to

speak is Diligence:

addres sing himself

to the students, he

canvasses for

allegiance and

promises his

followers happiness

and honour

(movements 2−3).

Then Happiness and

Honour themselves

appear and confirm:

indeed, for those

who are diligent,

the dwellings of

honour and the

cornucopia of

happiness will not

remain locked away

(movements 4−5).

After that,

Gratitude joins in

and points out

Kortte: these are no

empty promises; in

this man everything

has come true.

Preserve his memory,

etch it into marble

or, better still,

raise a memorial to

him by means of your

own actions

(movements 6−7). In

the last recitative

Diligence, Honour

and Happiness attest

how deeply they feel

devoted to Kortte,

and Gratitude urges

the friends of the

appointee to join in

with the good wishes

of the four

allegorical figures:

‘Long live Kortte,

may Kortte

flourish!’

Bach set this

attractively

conceived libretto

in music that is

even more appealing,

and he did so – as

always – with great

care and artistry.

Admittedly

profundity and depth

of meaning were not

uppermost in his

mind – and there is

no reason why they

should have been, in

such cheerful

‘Studentenmusik’. At

two places in the

score he had

recourse to an

earlier work: the Brandenburg

Concerto No. 1;

its third movement

appears here,

skilfully

transformed, as the

opening chorus,

whilst its second

trio (originally for

horns and oboes) is

rescored as a

postlude to the duet

aria of Happiness

and Honour (fifth

movement).

Bach’s musical style

reacts to the text,

as usual, with great

agility – to the

‘rolling drums’

mentioned in the

opening chorus and

which do in fact

‘roll’ – and

likewise, in the

middle of the final

chorus, to the

‘laurel’, the

tendrils of which

curl mellifluously

in the two flute

parts. In the

seventh movement

there is a

particularly

original

illustration of the

text. Gratitude

demands a memorial

for Kortte: ‘Etch

this remembrance

into the hardest

marble!’ Bach sets

this as a beautiful,

contemplative aria

with two flutes.

Within this music,

however, he already

depicts the stonemason

working on the

marble: we hear his

hammer blows

chiselling the name

into the stone,

quietly but un

mistakably, in the

unison strings. One

wonders if Bach ever

imagined that his

music might serve as

a musical memorial,

making the

professor’s name

familiar in

centuries to come.

© Klaus

Hofmann 2013

Production

Notes

BWV205

The only extant

material for this

composition is the

original full score

(Staatsbibliothek zu

Berlin, Mus. ms.

Bach P 173). The

orchestral parts no

longer exist, but

the instrumentation

can be ascertained,

since it is quite

clearly written down

at the beginning of

the manuscript.

An interesting

question concerns

the viola d’amore in

the fifth movement.

In Bach’s time, the

leader usually

played such solos.

In this case,

however, he would

have been required

to play the violin

in the tutti

in the third

movement, change

instrument to the

viola d’amore during

the short recitative

in the fourth

movement, while

having an extremely

challenging solo for

the violin ahead of

him in the ninth

movement. This would

seem like a nearly

impossible demand

on the player. Apart

from in this work,

the viola d’amore

appears in Bach’s

vocal music only in

BWV36c, BWV 152 and

the St John

Passion, but

in none of these

works is it clear

who in the orchestra

played this

instrument. In BWV

205/5 the viola da

gamba is also

required, so in the

case of this

instrument, too, one

of the players must

have switched

instruments in the

course of the work.

A final brief remark

regards the trumpets

and horns. Following

our recent practice,

the brass

instruments adopted

for this recording

are constructed

entirely according

to original baroque

practice, which

means that they lack

the so-called tone

holes (or venting

holes) with which

the intonation may

be adjusted on a

modern-day ‘baroque

trumpet’. In

consequence, it is

physically

impossible for their

11th (Fa) and 13th

(La) overtones to be

completely in tune.

It is, however, our

firm belief that the

sound, undisturbed

by the use of any

holes, remains

rounded and vivid,

and that the player

is able to achieve a

more legato and

singing character.

We hope that the

listener will enjoy

this ‘natural’

character which

should also be close

to the original

sound that Bach

himself will have

heard.

BWV207

The original full

score (Mus. ms. Bach

P 174) and the

orchestral parts (St

93) at the

Staatsbibliothek zu

Berlin are the

reference materials

that remain of this

cantata. Although

the original

manuscript has

survived, many

questions arise

regarding the

performance of the

piece. Several

problems must be

addressed, for

example in the

woodwind parts for

the first movement,

which include notes

outside of the

instruments’ ranges.

Also, the two parts

marked for the oboe

have not been

transposed and we

can only assume that

they were written

for oboe d’amore. As

for the flutes, the

second part often

descends below the

instrument’s lower

register so that the

player must double

the first flute part

each time this

occurs.

Another problem is

that in the original

full score, there is

an independent

movement called Marche;

however, it is

unclear where it

should be inserted

within the

composition. For

this performance, we

have decided to play

the movement as a

prelude to the final

chorus.

©

Masaaki Suzuki

2014

|

|