|

|

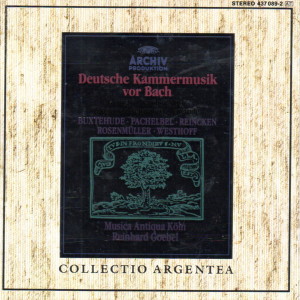

1 CD -

437 089-2 - (c) 1986

|

|

| 3 LP's -

2723 078 - (p) 1981 |

|

| DEUTSCHE

KAMMERMUSIK VOR BACH |

|

|

|

|

|

Johann Adam Reinecken

(1623-1722)

|

|

|

| 1. Sonata a-moll

- Violine

I/II, Viola da gamba;

Continuo: Cembalo |

15' 17" |

|

| - [Sonata:] Adagio -

Allegro -

Largo/Presto/Adagio/Allegro |

5' 32" |

|

| - Allemande ·

Allegro |

3' 17" |

|

| - Courante |

1' 41" |

|

| - Sarabande |

2'

15" |

|

- Gigue ·

Presto

|

2'

32" |

|

|

|

|

| Dietrich Buxtehude

(1637-1707) |

|

|

| 2.

Sonata B-dur BuxWV 273 - Violine,

Viola da gamba; Continuo:

Violone, Cembalo |

14' 30" |

|

| - [Sonata:] Ciaccona

- Adagio - Allegro/Adagio/Allegro |

7' 41" |

|

| -

Allemande |

2'

50" |

|

| -

Courante |

1'

01" |

|

-

Sarabande

|

1'

43" |

|

-

Gigue

|

1'

15" |

|

|

|

|

| Johann Rosenmüller

(1619-1684) |

|

|

| 3.

Sonata e-moll - Violine

I/II; Continuo:

Violoncello, Theorbe,

Orgel |

9' 52" |

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Paul von Westhoff (1656-1705)

|

|

|

| 4. Sonata "La

guerra" A-dur - Violine;

Continuo: Theorbe, Viola

da gamba, Cembalo |

12' 22" |

|

| - Adagio con una

dolce maniera - Allegro |

3' 06" |

|

| - Tremulo Adagio |

0'

54" |

|

| - Allegro ovvero

un poco presto |

0' 44" |

|

- Adagio

|

1' 01" |

|

- Aria (Adagio

assai)

|

2' 20" |

|

| -

La Guerra così nominata di sua

maestà |

0' 41" |

|

- Aria (tutto

Adagio)

|

2' 04" |

|

- Vivace

|

0'

16" |

|

- Gigue

|

1'

16" |

|

|

|

|

| Johann Pachelbel

(1653-1706) |

|

|

| 5.

Partie (Suite) G-dur - Violine,

Viola I/II; Continuo:

Violoncello, Theorbe,

Orgel |

10' 00" |

|

| - Sonatina |

1' 02" |

|

| - Allemande |

2' 46" |

|

| - Gavotte |

0' 50" |

|

| - Courante |

0' 56" |

|

| - Aria |

0'

38" |

|

| - Sarabande |

1'

37" |

|

| - Gigue |

1'

29" |

|

| - Finale. Adagio |

0'

43" |

|

| 6.

Canon & Gigue D-dur - Violine

I-III; Continuo:

Violoncello, Violone,

Cembalo |

4' 37" |

|

| - Kanon |

3'

08" |

|

| - Gigue |

1'

29" |

|

|

|

|

| MUSICA ANTIQUA

KÖLN |

|

| - Reinhard Goebel, Hajo Bäß, Mihoko Kimura, Barock-Violine |

|

- Karlheinz Steeb, Barock-Viola

|

|

| - Jaap ter Linden, Barock-Violoncello |

|

| - Jonathan Cable, Violone |

|

| - Konrad Junghänel,

Theorbe |

|

| - Henk Bouman, Cembalo

& Truhen-Orgel |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Plenarsaal

der Akademie der Wissenschaften,

Mũnich (Germania) - agosto 1980

(1,2), settembre 1980 (3,4,5),

novembre 1980 (6) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Engineer |

|

Andreas

Holschneider - Gerd Ploebsch /

Wolfgang Mitlehner |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Archiv

- 2723 078 - (3 lp's) - durata 50'

46" | 63' 02" | 51' 28" - (p) 1981

- Analogico - (parziale)

|

|

|

Edizione

"Collectio" CD |

|

Archiv

- 437 089-2 - (1 cd) - durata 66'

38" - (c) 1986 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

GERMAN

CHAMBER MUSIC

BEFORE BACH

The

German musical scene during

the early 17th century was

as diverse and fragmented as

the political map of the

crumbling Reich of

the Holy Roman Empire.

English viol players such as

Brade and Simpson gained a

footing at the princely

courts of central Germany

and in the northern

Hanseatic cities; pupils of

the great Dutch organist

Sweelinck, among them

Scheidt, Scheidemann and

Praetorius, occupied

positions as organists at

the principal centres of the

Protestant faith, while from

the south such virtuoso

violinists as Marini,

Farina, Turini and

Buonamente “imported” the seconda

prattica of their

mentor Claudio Monteverdi.

But: inter armae silent

musae - when weapons

clash the muses are silent.

The Thirty Years’ War which

broke out in 1618 destroyed

the cultural structure;

court musical establishments

were dissolved, and town

pipers and civic bands,

whose members had kept music

alive among the middle

class, also fell victim to

the terrible conflict. In

the words of Heinrich Schütz:

“Among the other free arts

the noble art of music has

not only suffered great

decline in our beloved

fatherland as a result of

the everpresent dangers of

war; in many places it has

been wholly destroyed, lying

amid the ruins and chaos for

all to behold.”

By the time peace was

concluded in 1648 after 30

years of war, Thuringia and

Saxony had lost more than

half of their population,

but even in those stricken

lands “the arts, which had

been trampled in the mud”

very soon rose up “by God’s

grace to their former

dignity and value”. The

tirelessly active Heinrich

Schütz

- pater musicae modernae

nostrae - and his

widespread circle of pupils

brought about a swift

renewal of Protestant church

music. In the instrumental

field, as regards both the

forms of composition and the

purely technical mastery of

performance, especially on

the then “modern” violin,

Italian musicians had

formerly been pre-eminent.

Distant Vienna, although

threatened by the Turks, did

not suffer directly from the

ravages of the Thirty Years’

War; musicians there

remained in close contact

with Monteverdi and his

pupils in Venice, thus

remaining à

la mode. In northern and

central Germany, however,

the cultivation of music

became dependent on local

resources, and it was not

until about 1680 that there

appeared a generation of

German instrumental virtuosi

and composers of both high

standing and pronounced

individuality. The

emancipation from the

predominance of Italian

instrumental music brought

about by the economic

hardships of the post-war

period was assisted by the

fact that the enthusiasm of

Italian musicians for the

violin and for monody, which

had led to the supremacy

of technique for its own

sake, had cooled down

noticeably; the sonatas of

Marco Uccellini, published

in 1649, which mark the

climax of the development of

violin technique since the

instrument’s introduction

into art music, reveal the

rift which had opened up

between form and content,

and mark the point in time

at which compositions by

Italian violinists turned in

the direction of formal

experiments, which were to

lead to the late Baroque

church sonata and to the

concerto. In other European

musical centres, too,

Italian supremacy was

challenged during the last

third of the 17th century.

In France Lully and his

pupils, at the command of

the young Roi Soleil

Louis XIV sought a

characteristically French

tonal language, England

experienced a last

blossoming of music for

viols at the hands of Henry

Purcell, in Vienna the

Emperor Leopold I appointed

Johann Heinrich Schmelzer as

primo violinista of

the Imperial Chapel, and

later as court

Kapellmeister, while in

northern Germany there

sprang up everywhere

“violin-gardens,

spring-fruits,

flower-clusters, and

keyboard-fruits”.

The formal layout of central

and north German chamber

music produced between 1680

and 1700 was marked by

sonata-form elements derived

from the Sonata

concertata of Dario

Castello with its solo

episodes framed by sonorous

ensemble sections, by suites

consisting of the customary

sequence of dance movements,

and by suite fragments

including pieces unrelated

to dances and generally

entitled “Aria” with free

introductory pieces of

various kinds described by

the word “Sonata”. The

two-section type of “sonata”

akin to the prelude and

fugue is more closely

related to the suite

movements which follow it

than the three- or

four-section opening

movement for a suite, which

is more emancipated and - as

we know from contemporary

accounts - was often played

independently, without the

suite to which it had

originally belonged.

Stylistically important are

the inner parts, “which do

not sit still” (Mattheson),

and which do not yet possess

the ad libitum

character of “filling-in”

parts such as are to be

found in French and Italian

ensemble music of the

period. The unique dual role

of the viola da gamba as a

solo instrument in the

alto-tenor register and as

an embellishing basso-concertante part

also arose out of the desire

for richness of sound and

polyphonic penetration of

the vertical harmonic

texture.

The summum opus of

German composition

instruction between Schütz

and Bach - evidently widely

distributed in manuscript

copies and well known - was

probably the Musicalisches

Kunstbuch by Johann

Theile, “the father of

counterpoint, as some call

him”, in which are set out

all the virtuosic fugal and

canonic devices to be

found throughout German

music of that time.

Collections of sonatas

published during the last

quarter of the 17th

century are founded on

various different

principles of

Construction. The custom,

common in Italy until

almost the beginning of

the 18th century, of

issuing works differing in

formal layout and scoring

as a single collection,

was abandoned in favour of

publishing half a dozen

sonatas - or sometimes

seven, corresponding to

the number of planets or

days in a week - scored

for the same instruments

and similar in

construction, and in a

sequence of keys either

ascending or descending

diatonically, or even

grouped in tonalities a

fifth apart, or standing

in some complex

symmetrical key

relationship. Paul von

Westhoff assembled his

sonatas for violin and

basso continuo of 1694 in

the sequence A minor- A

minor- D minor- D minor- G

minor-G minor, and the

recently discovered six

suites for solo violin are

in A minor- A major- B

flat major- C major- D

minor- D major.

Buxtehude’s Opus 1 are in

B flat major- D minor- G

minor- C major- A major- E

major- F major, and his

Opus 2 are in

F major- G major- A minor-

B flat major- C major-D

minor-E minor, and

Reincken’s Hortus

Musicus

in A minor- B flat

major- C major- D minor- E

minor- A major.

The earliest work in this

anthology is probably the

sonata of Johann

Rosenmüller,

born at Oelsnitz in Saxony

in 1619, who from about

1660 lived at Venice, from

where he supplied sacred

vocal music for courts in

central Germany. The

dedication of his fourth

and last collection of

sonatas to Duke

Anton-Ulrich of Brunswick

is dated 31 March 1682.

Form-creating repetitions

of entire sections of

movements, scanning

Adagios full of expressive

pauses with purely

rhetorical harmony as

transitions to slow

movements rich in soaring

melodies and sombre fugues

with chromatic lamento

themes mark the Sonata in

E minor.

Dietrich Buxtehude

was organist at the

Marienkirche in Lübeck

from 1664. His Sonata in B

flat major, BuxWV 273 - an

early version in

manuscript of the sonata

published as Op.1 No.4

- is notably advanced for

its time on account of its

three-movement form and

the concertante

treatment of the two solo

instruments in the

introductory Chaconne,

which features various

contrasting ideas, but

which is given inner unity

by frequent reappearances

of its triadic motif; the

opening motif of the fuge

is a further variant of

the triadic figure. In the

later printed version

Buxtehude altered the

Adagio which leads to the

Fugato: he removed, for

the sake of a smoother

flow of the last movement,

the adagio marking

of the stylized trill

figure which retards the

progress of the movement,

and he sacrificed,

too, the appended violin

suite, in which the viola

da gamba, used elsewhere

in a solo capacity, mainly

fulfils the function of a

continuo instrument.

Johann

adam Reincken,

who had studied under

Sweelinck’s pupil Heinrich

Scheidemann, was a friend

of Buxtehude, and also

joint founder with Johann

Theile of the Hamburg

Opera opened in 1678,

published his Hortus

Musicus in 1688.

This comprises six

sonatas, all of which

follow the same formal

pattern, well proportioned

within themselves and

organized as a group in

such a way as to

demonstrate the

characteristics of both

sonata and suite, also

marked by complete mastery

of emotional effects, the

whole collection forming

by far the most important

ensemble music of the late 17th

century.

Janus-faced

between the sonata and the

suite is a two-section

solo for violin which is

repeated unaltered by the

viola da gamba. In

the solo of the Sonata in

A minor the “figuration

idea” of the preceding

permutation fugue (the

incessant semiquaver

momentum) is taken up,

while figuration of the

Allemande to follow is

foreshadowed. The

Allemande and Courante

have their subject matter

in common, i.e. the

Courante is merely a tripla

variant of the Allemande;

the Gigue - also a

permutation fugue without

interludes - is in two

sections, with the second

section essentially a

mirror image of the first.

It is also related to the

introductory Sonata

through the similarity of

its themes.

While German

characteristics are most

clearly evident in the

sonatas of Buxtehude and

Reincken, Paul von

Westhoff combined

the Italian dolce maniera

and French grace with the

fruits of German violin

technique in his sonata

played before Louis XIV in

1682. This first

work of Westhoff published

- together with a suite

for solo violin, also

written in Paris, in the Mercure

Galant during 1682

accompanied by an account

of how the Roi Soleil

was so enthusiastic about

Westhoff's performance

that he ordered him to

repeat it twice - is

constructed from

contrasting elements in

accordance with the

principles of the High

Baroque virtuoso sonata.

The combination, rich in

contrasts, of slow

sections as solos and

quick ones as ensembles

and their opposites gives

rise to a four-section

layout marked by inner

symmetry.

Southern euphony is

radiated by the chamber

music of Johann

Pachelbel, who after

learning his craft at the

Imperial court in Vienna

worked at Erfurt,

Eisenach, Gotha,

Stuttgart, and finally

his native city of

Nuremberg. Connections

with Johann Kaspar Kerrl,

with the Bach family and

such contemporaries as

Daniel Eberlin (later to

be Telemann’s

father-in-law) and

Dietrich Buxtehude (to

whom he dedicated his Hexacordum

Apollinis) made

Pachelbel a link between

the Catholic south and the

Protestant north, one of

the central figures of the

High Baroque musical scene

in Germany. The appearance

of a solo violin above a

consort of deep-toned

stringed instruments is

reminiscent - like the

restrained sweetness of

the arias - of Heinrich

Schmelzer, while scordatura

and the melting Chaconne,

exchange of parts in the

repeats of the arias, and

the technique of the canon

in unison point to the

posthumously published Harmonia

Artificiosa

of H. I. F. Biber.

The generation of musicians

who died during the first

decade of the 18th century -

Pachelbel, Biber, Westhoff,

Buxtehude, and Reincken, who

remained active until the

age of 99 - these and many

others created the climate

in which Johann Sebastian

Bach grew to maturity. We

should understand his

arrangements and

performances, quotations

from and copies of works by

Pachelbel, Reincken, Rosenmüller,

Kuhnau and Kerrl as marks of

respect for the creations

ofthe older masters!

Reinhard

Goebel

(Translation:

John Coombs)

|

|