|

|

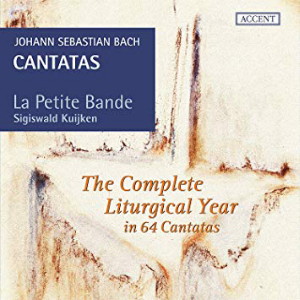

1 CD -

ACC 25301 - (p) 2005

|

|

KANTATEN FÜR DAS GANZE

KIRCHENJAHR

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ADVENTSZEIT |

|

BWV |

|

ADVENT |

Volume |

1. Advent

|

|

61 |

|

Nun

komm, der Heiden Heiland

|

9 |

|

|

36 |

|

Schwingt

freudig euch empor

|

9 |

|

|

62 |

|

Nun

komm, der Heiden Heiland

|

9 |

4. Advent

|

|

132 |

|

Bereitet

die Wege, bereitet die Bahn!

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| WEIHNACHTSZEIT |

|

BWV |

|

CHRISTMASTIDE |

Volume |

| 1. Weihnachtstag |

|

91 |

|

Gelobet

seist du, Jesu Christ |

14 |

| 2. Weihnachtstag |

|

57 |

|

Selig

ist der Mann

|

14 |

| 3. Weihnachtstag |

|

151 |

|

Süßer

Trost, mein Jesus kömmt

|

14 |

1. Sonntag nach

Weihnachten

|

|

122 |

|

Das

neugeborne Kindelein |

14 |

| Neujahr |

|

16 |

|

Herr

Gott, dich loben wir

|

4 |

| 1. Sonntag nach

Neujahr |

|

153 |

|

Schau,

lieber Gott, wie meine Feind

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPIPHANIASZEIT |

|

BWV |

|

EPIPHANY SEASON

|

Volume |

| Epiphanias |

|

65 |

|

Sie

werden aus Saba alle kommen

|

4 |

| 1. Sonntag nach

Epiphanias |

|

154 |

|

Mein

liebster Jesus ist verloren

|

4 |

| 2. Sonntag nach

Epiphanias |

|

13 |

|

Meine

Seufzer, meine Tränen

|

8 |

| 3. Sonntag nach

Epiphanias |

|

73 |

|

Herr,

wie du willt, so schicks mit mir

|

8 |

| 4. Sonntag nach

Epiphanias |

|

81 |

|

Jesus

schläft, was soll ich hoffen?

|

8 |

Mariä Reinigung

|

|

82 |

|

Ich habe

genug

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| VOR-PASSION |

|

BWV |

|

PRE-LENTEN SEASON

|

Volume |

| Septuagesimæ |

|

144 |

|

Nimm,

was dein ist, und gehe in

|

8 |

| Sexagesimæ |

|

18 |

|

Gleichwie

der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel fällt

|

6 |

| Estomihi |

|

23 |

|

Du

wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PASSIONSZEIT |

|

BWV |

|

PASSIONTIDE |

Volume |

| Invocavit |

|

1 |

|

Wie

schön leuchtet der Morgenstern

|

6 |

| Oculi |

|

54 |

|

Wiederstehe

doch der Sünde

|

17 |

| Palmarum |

|

182 |

|

Himmelskönig,

sei willkommen

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ÖSTERLICHE

FREUDENZEIT

|

|

BWV |

|

EASTERTIDE |

Volume |

| Ostersonntag |

|

249 |

|

Kommt,

eilet und laufet ihr fl#chtigen F#ße

|

13 |

| 2. Osterfesttag |

|

6 |

|

Bleib

bei uns, denn es will Abend werden

|

13 |

| 3. Osterfesttag |

|

134 |

|

Ein

Herz, das seinen Jesum lebend weiß

|

17 |

| Quasimodogeniti |

|

67 |

|

Halt im

Gedächtnis Jesum Christ

|

11 |

Misericordias

Domini

|

|

85 |

|

Ich bin

ein guter Hirt

|

11 |

| Jubilate |

|

12 |

|

Weinen,

Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen

|

11 |

| Cantate |

|

108 |

|

Es ist

euch gut, daß ich hingehe

|

10 |

| Rogate |

|

86 |

|

Wahrlich,

wahrlich, ich sage euch

|

10 |

| Ascensio |

|

11 |

|

Lobet

Gott in seinen Reichen

|

10 |

| Exaudi |

|

44 |

|

Sie

werden euch in den Bann tun

|

10 |

1. Pfingstfesttag

|

|

34 |

|

O ewiges

Feuer, o Ursprung der Liebe

|

16 |

| 2. Pfingstfesttag |

|

173 |

|

Erhöhtes

Fleisch und Blut

|

16 |

| 3. Pfingstfesttag |

|

184 |

|

Erwünschtes

Freudenlicht

|

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TRINITATISZEIT |

|

BWV |

|

TRINITY AND ORDINARY TIME

|

Volume |

| Trinitatis |

|

129 |

|

Gelobet

sei der Herr, mein Gott

|

16 |

1. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis

|

|

20 |

|

O

Evigkeit, du Donnerwort

|

7 |

| 2. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

2 |

|

Ach

Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein

|

7 |

| Visitatio |

|

10 |

|

Meine

Seel erhebt den Herren

|

7 |

| 3. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

135

|

|

Ach

Herr, mich armen Sünder

|

2

|

| 4. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

177 |

|

Ich ruf

zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ

|

2 |

| 5. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

93 |

|

Wer nur

den lieben Gott läßt walten

|

2 |

| 6. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

9 |

|

Es ist

das Heil uns kommen her

|

18 |

| 7. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

186 |

|

Ärgre

dich, o Seele, nicht

|

18 |

| 8. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

178 |

|

Wo Gott

der Herr nicht bei uns hält

|

3 |

| 9. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

168 |

|

Tue

Rechnung! Donnerwort

|

18 |

| 10. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

102 |

|

Herr,

deine Augen sehen nach dem Glauben

|

3 |

| 11. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

179 |

|

Siehe

zu, daß deine Gottesfurcht nicht

Heuchelei sei

|

5 |

| 12. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

35 |

|

Geist

und Seele wird verwirret

|

5 |

| 13. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

164 |

|

Ihr, die

ihr euch von Christo nennet

|

5 |

| 14. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

17 |

|

Wer Dank

opfert, der preiset mich

|

5 |

| 15. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

138 |

|

Warum

betrübst du dich, mein Herz

|

12 |

| 16. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

27 |

|

Wer

weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende?

|

12 |

| 17. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

47 |

|

Wer sich

selbst erhöhet, der soll erniedriget

werden

|

12 |

| 18. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

96 |

|

Herr

Christ, der einge Gottessohn

|

12 |

| 19. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

56 |

|

Ich will

den Kreuzstab gerne tragen

|

1 |

| 20. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

180 |

|

Schmücke

dich, o liebe Seele

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ENDE DES

KIRCHENJAHRES

|

|

BWV |

|

END OF THE LITURGICAL YEAR

|

Volume |

| 21. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

98 |

|

Was Gott

tut, das ist wohlgetan

|

1 |

| 22. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

55 |

|

Ich

armer Mensch, ich Sündenknecht

|

1 |

| 23. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

52 |

|

Falsche

Welt, dir trau ich nicht!

|

15 |

| 24. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

60 |

|

O

Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort

|

15 |

| 25. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

116 |

|

Du

Friedefürst, Herr Jesu Christ

|

15 |

| 26. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

70 |

|

Wachet!

betet! betet! wachet!

|

18 |

27. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis

|

|

140

|

|

Wachet

auf, ruft uns die Stimme

|

15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bach Cantatas for the

Complete Liturgical Year

The project of recording one cantata

composed for each Sunday and high

feast of the liturgical year

has

been spread over several concert

seasons, during each of which three

to four cantatas

were

given concert performances and were

recorded. As far as possible this

was made

during

the relevant time of the year for

which the cantatas were written.

GENERAL

INTRODUCTION

getting the best from

listening to the Bach cantatas

It

seems to me essential that those

really wanting to

absorb and appreciate these cantatas

should turn their

attention to the respective text as

dispassionately and

open-heartedly as possible before

listening to

each work.

The librettists and

composers of the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries took it for

granted that the

congregation for which the cantatas

were intended were

familiar with the themes they dealt

with, since the texts

were written for liturgical use. They

therefore always followed upon the

prescribed readings

from the Old and New Testaments. By

nature they were a

fabric of paraphrases and

commentaries on

those readings, and as such they

were given

personal, poetic treatment.

The majority of

cantata texts from Bach’s time and sphere

of influence have a ‘collage’

structure made up

of at least two layers of different

origins. Almost all

the cantatas contain one or more

stanzas of a Lutheran

hymn (mostly from the seventeenth

century, sometimes

from the late sixteenth century, in

more or less

unchanged form) which are

integrated with the newly written

texts. Being able to recognize this double-layered

structure then helps us to “feel” it as well. More

than just a structural process, the “collage” often allows

us to better perceive the core of the central ideas.

There are a number of

variations on this basic structure; in the texts of

the oratorios and passions (which are very closely

related to the cantata texts), there is yet a third layer:

fragments of the Gospel text (in Luther’s

translation). There are also

examples of cantata texts in which

fragments of Old-Testament texts form a third layer –

occurring mostly at the beginning of the

cantatas, as a kind of “statement

of the theme”. The fact

that, unlike the hymns and the new texts, these

two forms of text (Gospels and Old Testament) are not

presented in poetically revised form but as prose

(that is, without definite metre and rhyme), lends

these “triple-layered” texts not only greater structural

complexity but also a directly perceptible degree

of declamatory variety.

A special case is represented by

the CHORALE

CANTATA,

which in turn may be divided into

two types. In the first type the

entire text consists of a

selection of stanzas from a

familiar hymn (i.e. without “new

texts”), while in the second type

mostly only the beginning and end

of the cantata text are stanzas

taken over literally from an

existing hymn, while the rest

comprises paraphrases of other

stanzas of the same hymn.

In 1724 Bach composed cantatas of

that kind for an almost complete

liturgical year, filling in the

gaps at a later time.

Insight into the structure and

perception of the various sources

of the individual parts provides

clarity about the text in its

entirety; it is important to

recognize how the poet linked the

parts with one another. It is

obvious that knowledge of and

sympathy with articles of

Christian faith are of great

assistance in this. But whether

(or how deeply) we are touched by

the verses will ultimately depend

solely upon the librettist’s

poetic talent.

Because the librettist repeatedly

presented aspects of generally

familiar leitmotifs in these

texts, he sought to emphasize them

in a personal and compelling

manner by applying every stylistic

device available to poetry and

rhetoric at the time. The informed

assessment and conscious enjoyment

of such poesy is in my opinion

unthinkable without a certain

amount of practice and the ability

to recognize at least the basic

principles underlying it.

In what follows I will try to

provide those who have little

experience in this subject with

certain key concepts, with the aid

of which they will be in a

position to recognize the context

and quality of these texts. Since

one of the hallmarks of all

Baroque art is that a certain

degree of priority is assigned to

the formal treatment (the “how?”)

over the originality of content

(the “what?”), I intend to

concentrate on the assessment and

enjoyment of the formal treatment

more than on the assessment of the

content of the texts - modern

listeners will all have their own

personal relationships to

spirituality in general and to the

Lutheran tradition (to which Bach

belonged) in particular.

The hymns and chorales (the

‘simpler’ layer of our cantata

texts) had the primary function of

edifying the congregation with

pious thoughts after the reading

from the Gospels. Definite rhythm

(e.g. poetic metre, see below) and

musically interesting rhyme have

from time immemorial been an

invaluable aid to memorizing – to

being able to keep something in

one’s head. Rhythm and rhyme have

therefore always played an

important role in hymns (just as

in children’s songs).

In the other layer, that of the

newly written texts (recitatives

and arias), the same tools (metre

and rhyme) are present, but here

they have often been developed

into sophisticated artifices of

various kinds which go far beyond

“edifying” or “catechizing” the

congregation.

In these texts the librettists

delved deeper into the toolbox of

ars poetica, not shying

away from implementing their own

ideas or from using metaphors

based mostly on ones in the Holy

Scriptures or in classical

writings. The listener was assumed

to be able to follow the countless

allusions to them and to understand their sense.

Art was at that time anyway much

more closely associated with

culture, which was “above” lowly

“nature”; and when homage was

rendered to ‘nature’ in the art

of the early eighteenth century,

it must be understood that it

was not done in the ‘Romantic’

sense, nature rather being seen

as an idealized model and not as

the ‘raw material’ from which

all that is good comes.

Realistic naturalism was unknown

in art, the word “artificial”

commonly having the same

positive denotation as

“artistic” and being used even

to describe the excellence of

craftsmanship.

That makes it easy to understand

that in order to serve their art

the librettists used the arsenal

of poetic devices freely, with

conviction and imagination. RHYTHM determines

the course of the verses: the

choice and alternation of the

various metrical feet (the

rhythmic ‘cells’ which are

repeated in the syllables of a

verse) and the verse structures

aim directly at the deepening of

expressiveness; thus the ideal

form at the same time becomes

virtually a part of the content.

As in the hymns of earlier

decades, the following metrical

feet predominate:

- the IAMB

(one short syllable and one long

syllable)

- the TROCHEE

(one long and one

short)

- the DACTYL

(one long and two

short)

These metres (and others, like

the spondee, longlong) all came

down to us from classical Greek

and have pervaded the poetry of

the entire Western world for

several millennia, though in our

languages, the long-short

dichotomy has rather come to

mean strong-weak stress.

Each metre tends to have its own

“psychological effect”. Iambic

metre predominates in the

cantata texts, mostly in

peaceful and regular narration;

trochaic metre often seems more

powerful, urgent, sometimes

almost imperious; dactylic metre

creates the impression of sudden

acceleration and motion by

virtue of its strong beat

followed by two weak ones (the

strong-weak alternation of the

iamb and trochee being analogous

to the two-to-one pattern of

triple time in music), whereas

the – rare – spondee, composed of

two equally strong beats,

creates a noticeably more

melancholy impression.

A little practice is required to

recognize the metres, but one

soon becomes accustomed to

noticing them and is rewarded

with a greater feel for the

verses. I should like to urge

listeners to get the knack of

reading this poetry through

silently or aloud in the

rhythmically correct manner;

doing so is the only way to

perceive its inner structure and

fully enjoy its beautiful

aspects.

The following examples from

Bach’s cantata texts may be used

for reference whilst practising

the technique:

IAMBIC METRE:

(short-long)

Cantata 55, of Aria

no. 1:

Ich armer Mensch,

ich Sündenknecht,

Ich geh vor Gottes

Angesichte

Mit Furcht und Zittern

zum Gerichte,

Er ist gerecht,

ich ungerecht

TROCHAIC METRE: (long-short)

Cantata 55, Aria no. 3, lines

3 to 6:

Lass die Tränen

dich erweichen,

Lass sie dir zu Herzen

reichen;

Lass um Jesu

Christi willen

Deinen Zorn

des Eifers stillen

DACTYLIC METRE:

(long-short-short)

(Each line begins on a short

syllable on the ‘upbeat’ of the

preceding bar before the first

complete dactyl; this is not in

keeping with classical Greek

Poetry)

- Cantata

19, opening chorus (lines 2

and 3):

Die rasende Schlange,

der höllische Drache

Stürmt wider den

Himmel mit wütender

Rache

- Cantata

21 contains an aria which

‘skips’ along in dactyls

throughout (no. 10):

Erfreue dich, Seele,

erfreue dich, Herze,

Entweiche nun, Kummer,

verschwinde nun, Schmerze!

Verwandle dich, Weinen,

in lauteren Wein!

Es wird nun mein

Ächzen ein Jauchzen

mir sein.

(and so on in three more

verses)

The following examples

illustrate the CHANGE OF THE BASIC RHYTHM (i.e.

the metre) within a fragment,

both from Cantata 56 “Ich

will den Kreuzstab gerne

tragen”:

- In Aria no. 1 the

pilgrimage through life “to God

in the Promised Land” is told in

iambic verse; suddenly (so to

speak upon “arriving” there),

the metre becomes dactylic and

we impulsively, musically, sense

thereby man’s joy at finding

salvation in God:

Ich will den Kreuzstab

gerne tragen,

Es kömmt von Gottes

lieber Hand,

Der führet mich

nach meinen Plagen

Zu Gott in das

gelobte Land

(iambic thus far)

Da leg ich den Kummer

auf einmal ins Grab

(dactylic from

here)

Da wischt mir die

Tränen mein Heiland

selbst ab.

Interestingly, the poet (or was

it J. S . Bach himself?) used

the last two (dactylic) lines

once again at the end of the

recitative no. 4 (which, like

the above aria, is otherwise

iambic), again achieving a

similar effect directly before

the closing chorale.

- In the third line of Aria

no. 3 the poet switches

from trochaic to iambic metre,

returning to trochaic in the

closing line; that creates a

structure which intensifies the

expressiveness of the whole

aria; the iambic lines (3 to 6)

form a definite unit which is

framed by the three essentially

related trochaic lines (1, 2 and

7):

Endlich, endlich

wird mein Joch

Wieder von

mir weichen müssen.

(trochaic thus far)

Da krieg ich in

dem Herren Kraft,

(iambic from here)

Da hab ich Adlers

Eigenschaft,

Da fahr ich auf

von dieser Erden

Und laufe sonder

matt zu werden.

O gescheh

es heute noch!

(again trochaic)

An unchanging metre can

naturally become monotonous, but

the skillful librettist is able

to use these regular rhythms

ingeniously, to bend them, to

distort them. Sometimes, for

example, important words or

syllables are placed in weak

(short, unaccented) positions;

that, in an intelligent

declamation, actually gives them

a special, artistically elevated

value - by virtue of being the

exception to the rule, this

unexpected device suddenly

heightens the listener’s

raptness.

- An example in the first

Aria of Cantata 55:

Ich armer Mensch,

ich Sündenknecht

(line 1, etc.)

Er ist gerecht,

ich ungerecht

(line 4)

In this clearly iambic context,

the pronoun “ich” (I) is twice

assigned a weak stress in the

first line (the “short” instead

of the “long” syllables of the

iambic feet). In the 4th line,

both “Er” (He, i.e. God) and

“ich” are similarly weak. An

unsophisticated, schematic

declamation would render these

four syllables as relatively

unimportant. However, it is all

too clear that the poet’s

repetition of ‘ich’ in contrast

to ‘Er’ in the fourth line is

intended to intensify ‘ich’; the

sinner is here contrasted with

the just God. Both instances of

ich in the first line should

therefore deliberately be

treated as an exception and

given a certain degree of

expansion and weight (even

silently in reading!); the same

applies to Er and ich in the

fourth line.

These examples will without

doubt enable one to realize how

correct declamation can help to

shape the content of a text.

- EXCLAMATIONS (like “Ach!”, “O”

and “Wie”), and monosyllabic

words like “nun” - “so” –

“welch” etc. also very often

occur at points of weak stress,

although in declamation they

must frequently convey a certain

degree of passion, which at the

same time serves to avoid

monotony.

- PATHOS-LADEN APPEALS, like

“Herr” and “Gott”, as well as

monosyllabic contractions like

“komm”, “zeig” etc. also

frequently occur at such points

of ‘weak’ stress. Correct

declamation will then also

immediately emphasize and

exploit such cases.

Many other mechanisms and

beautiful aspects that cannot be

mentioned here will reveal

themselves as one makes progress

in reading the texts in this

manner. Intensive involvement

with the subject will make the

building blocks of Baroque

poetry and rhetoric easy to

recognize, and it is fun to

follow that path!

A final marginal note:

J. S . Bach involved himself

with this poetry with

astonishing energy and supreme

skill; for him it was modern and

alive, and he must also have had

a thorough knowledge of its laws

and subtleties.

Nonetheless, the musical

language of Bach and his time

was so highly developed and so

uniquely complex that composers

could not afford (nor did they

want) to be slaves to poetic

rules. For that reason, many

poetic peculiarities that make

up the charm of these verses had

to be sacrificed in setting them

to music because of

compositional considerations;

whereas the prosody (the

rhythmic flow of words) in the

recitatives is very close to

‘spoken’ declamation, in arias,

duets and polyphonic “choruses”

they naturally depart

considerably from the declaimed

pattern; there the laws of music

are given priority over those of

poetry.

Why then, one will ask, bother

with this long introduction to

specifically poetic aspects

(metrical feet etc.), if they so

often receive relatively little

attention in the composers’

musical settings? Because we

should nevertheless try to

experience these texts in the

same way as composers and

worshippers experienced them at

the time.

Only then can we truly

appreciate them. To listen “to

the music only”, without that

kind of insight into

the texts, seems me a deplorable

self-imposed restriction.

Logical structuring in rhythmic

cells is a very frequent

procedure in Bach’s music; many

of these rhythmic cells are

simple like metrical feet. Bach

sometimes takes the liberty of

changing the metre of the

original text, giving it another

rhythmic unit in his music.

For example, in Cantata 180

(Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele),

where the iambic metre of the

text in the tenor aria “Ermuntre

dich: dein Heiland

klopft” (be lively, your Saviour

knocks) is replaced in the

obbligato flute part and also

in the tenor solo with a

rhythmic impetus that is

clearly of dactylic nature.

The cheering quality of the

text is expressed in a much

livelier manner in this new

rhythm than in the poet’s

iambic metre. Here Bach worked

as a poet and “corrected” his

librettist.

In other cases, Bach follows

the metrical units of the text

precisely, using them as the

basis for erecting a large

edifce (what better example

could there be than the

beginning of the St

Matthew Passion: “Kommt,

ihr Töchter, helft

mir klagen”,

etc.?) Trochaic rhythm

(long-short) dominates the

whole opening chorus, being

omnipresent in its original

form in the bass of the

orchestra and taken up now and

then by the violas. In the

choral parts it is often

veiled by lengthy melismas

before returning clearly at “...helft

mir klagen”,

and later at “Holz

zum Kreuze selber

tra(gen)”.

We herewith conclude the

general textual commentary.

THE USE OF

VOCAL FORCES IN BACH'S

MUSIC

Musicological

research in recent decades

(above all by Joshua Rifkin

and other musicians like

Andrew Parrott) has made it

clear that J.S. Bach was not

thinking of a choir in the

modern sense when he wrote

his cantatas, passions,

masses, etc. Works of that

kind were then invariably

performed with a single

singer (“concertista”) for

each part (soprano, alto,

tenor, bass). These

“concertisti” sang not only

the solo arias and

recitatives relevant to

their voices, but also came

together to form the

“choir”, where necessary.

In rare cases, this quartet

of ‘concertisti’ was

reinforced by another

quartet, the ‘ripieno

singers’, who doubled the

concertisti only in the

ensemble sections (which is

what ripieno implies).

Bichoral works of this genre

therefore called for two

groups of four

‘concertisti’.

That was the normal way to

perform such church music in

Bach’s time and sphere of

influence; the solo forces

were taken for granted in

this context, and only the

vocally much simpler

contrapuntal works of the

old tradition were performed

with (often multiple)

doubling of the parts.

Many virtuosic passages in

the “choral sections” of

Bach’s cantatas etc. are in

my opinion also proof of the

fact that this was not

choral music in the modern

sense – just as a Haydn

string quartet, for example,

is not “music for string

orchestra”!

The terms “choir” and

“chorus” generally referred

to a “group” in the

seventeenth and early

eighteenth centuries, and

did not specifically imply a

doubling of the parts; a

solo quartet (even one

mixing voices and

instruments!) is also

referred to in certain

contexts as a “choir”.

Ultimately this music can

show its true face only if

performed by soloists. Since

the “conductor” in the

modern sense is dispensable

in that kind of performance

(I conduct, where necessary,

from the first violin),

these cantatas and related

pieces gain greatly in terms

of collective devotional

power.

ON THE

INSTRUMENTAL FORCES,

ESPECIALLY THE CONTINUO

GROUP

It is my conviction that

thorough critical

consideration must be given

to the automatic way in

which the cello “naturally”

forms part of the basso

continuo section in Baroque

music nowadays.

The word “violoncello”

occurs rather seldom in the

scores of the seventeenth

and early eighteenth

centuries; it was a specific

indication which was not

connected per se with the

general basso continuo, but

rather denoted a solo

function. The first

‘permanent’ role assigned to

the instrument was in the

“concertino”, i.e. the solo

group comprising two violins

and a “violoncello” which

was pitted against the

larger tutti section in the

concerto grosso.

The usual instrument given

the general bass role

(fondamento) was the

“violone”, which means

“large viola”. The viola

family had two branches: the

viola da

gamba and the viola da braccio.

Both were made in various sizes,

from descant (soprano) to bass.

Large instruments of both

families were assigned the

function of the ‘violone’, often

indiscriminately; in the absence

of norms, general use was made

of instruments of various sizes,

forms, tunings and pitches (some

sounded at “8-foot” pitch as

written, others sounded an

octave lower at “16-foot”

pitch). In the Italy of Corelli

(Rome, around 1700), the common

8-foot bass was called “violone”

and the octave bass

“contrabasso”. In works

demanding large orchestral

forces, the instruments were

listed as “violini, violette (=

violas), violoni, contrabassi”.

The “violoncello” clearly did

not belong to the usual

orchestral arsenal!

It is not clear exactly when

this smaller “violoncello”

(diminutive of violone!) became

obligatory in the various areas

of Europe. It is also not clear

how the cello was held – between

the legs as we know it, or

almost horizontally across the

chest, supported on (or against)

the right shoulder, as the

“Violoncello da Spalla alla

moderna” was described by

Bismantova of Ferrara in 1694.

The scores themselves do not

elucidate the matter.

I very much tend to regard the

leg position as having come

later than the “spalla

(shoulder) position”. As late as

1756, in the section in which he

describes the viola da gamba,

Leopold Mozart says the

instrument is ‘of course held

between the legs’ (as the name

suggests). He goes on: “Nowadays

the cello is also held

between the legs”, which clearly

implies that that was not the

case in earlier times. And

Adlung (Erfurt, 1758) writes two

years later: “The violoncello is

also called viola da spalla”

(the names ‘viola da spalla’ and

‘violoncello da spalla’ referred

to the same instrument).

In 1713 Mattheson praised the

viola da spalla at some length

because of its easiness to play

and strongly incisive” sound,

declaring that “nothing hinders

or prevents its resonance in the

slightest”. Brossard’s

Dictionnaire de musique of 1703

compared the “violoncelle des

Italiens” with the “quinte de

violon” in France – which again

points very clearly in the

direction of “spalla”, since the

quinte de violon was the largest

of the three violas in Lully’s

orchestra – all of which were

performed on the arm (the

“spalla position” is essentially

a consequence of the arm

position: since the instrument

was too large to rest on the

left shoulder or arm like the

smaller da-braccio instruments,

it was held horizontally across

the chest against the right

shoulder, sometimes with the aid

of a sling).

In Weimar in 1708, the year in

which Bach became court

organist, the “violoncello” was

likewise described as a “da

spalla” instrument.

The violoncello da spalla had

four strings and mostly used the

same tuning as today’s cello;

there is also (occasional)

mention of it having five

strings, in which

case a high e’ string was added.

That variant completely

corresponds with the so-called

“viola pomposa” which, according

to a report from around 1770,

had been ‘invented’ by J. S .

Bach in Leipzig in the 1720s.

Bach himself never actually uses

the name, but his Cello

Suite no. 6 requires its

tuning of CGdae’ (as do some of

the arias with violoncello

piccolo in the cantatas). The

five-string da-spalla instrument

combines the normal tunings of

the CGda cello and of the Gdae’

‘cello piccolo’.

It is increasingly assumed that

Bach conceived his “Cello

Suites” (and the solo violin

works) whilst still in Weimar;

it is certainly true that the

parts for the violoncello

piccolo solo passages in the

later Leipzig cantatas were

either written on separate

sheets or in the first violin

part, but never in the violone

or basso continuo parts. That

points once again to the “cello”

being held in the spalla

position in Bach’s environment.

The conclusion that his famous Cello

Suites and all his other

cello parts were intended for

the “violoncello da spalla” can

now in my opinion hardly be

called into question.

We put these ideas into

practice. Throughout our

recordings and versions, we use

– when ever violoncello is asked

for specifically by Bach – an

instrument built by Dmitry

Badiarov (Brussels) in 2004,

which is similar to the copies

of the “viola pomposa” in the

Leipzig and Brussels museums.

While designed for five strings,

it is also very well suited for

use as a four-string cello (or

cello piccolo).

The decision to use that

instrument is completely in

keeping with our feeling that

the needs of such small forces

(vocal and instrumental) are

best served by an 8-foot

“violone” (but an instrument

considerably larger than today’s

cello). For example, the 8-foot

violone of the ‘braccio family’

was the instrument that was

called ‘basse de violon’ in

France; in other parts of Europe

it was simply called ‘basso’ or

‘violone’. We use such

instruments; the 8-foot violone

of the gamba family is also used

in some cantatas.

The other stringed instruments

we use comprise 2 (or 3) first

violins, 2 second violins, 1

viola. This combination is

repeatedly found in the numerous

complete original sets of the

parts of Bach’s cantatas

which have come down to us.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation: J &

M Berridge

|

|

|