|

|

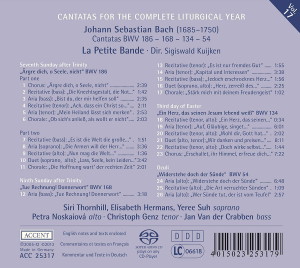

1 CD -

ACC 25318 - (p) 2012

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25318 - (p) 2012 - rectus

|

|

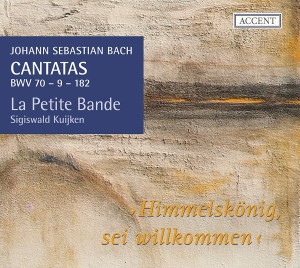

CANTATAS -

Volume 18

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Wachet! betet!

betet! wachet!", BWV 70 |

|

26' 24" |

|

| Part one |

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Wachet! betet! betet!

wachet! |

3'

27"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass):

Erschrecket, ihr verstockten Sünder! |

1' 08" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Wenn kommt der

Tag, an dem wir ziehen |

3' 59" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Auch bei

dem himmelischen Verlangen |

0' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Lasst der

Spötter Zungen schmähen |

2' 31" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Jedoch

bei dem unartigen Geschlechte |

0' 35" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Freu dich sehr, o

meine Seele |

1' 11" |

|

|

| Part two |

|

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Hebt euer Haupt

empor |

2' 57" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Ach, soll

nicht dieser große Tag |

1' 49" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Seligster

Erquickungstag |

3' 04" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Nicht nach Welt, nach

Himmel nicht |

0' 52" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Es ist das Heil

uns kommen her", BWV 9 |

|

22' 14" |

|

| -

Chorus: Es ist das Heil uns

kommen her |

4' 47" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Gott gab

uns ein Gesetz |

1' 16" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Wir waren schon

zu tief gesunken |

5' 29" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Doch

musste das Gesetz erfüllet werden |

1' 13" |

|

|

| -

Duet (soprano, alto): Herr,

du siehst statt guter Werke |

7' 05" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Wenn wir

Die Sünd aus dem Gesetz erkennen |

1' 24" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ob sich's anließ, als

wollt er nicht |

1' 00" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Palmarum |

|

|

|

| "Himmelskönig,

sei willkommen", BWV 182 |

|

25' 17" |

|

| -

Sonata |

1' 52" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Himmelskönig, sei

willkommen |

3' 12" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Siehe, ich

komme, im Buch ist von mir

geschrieben |

0' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Starkes Lieben |

2' 03" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Leget euch dem

Heiland unter |

7' 28" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Jesu, laß durch

Wohl und Weh |

3' 19" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Jesu, deine Passion

ist mir lauter Freude |

2' 41" |

|

|

| - Chorus: So lasset uns

gehen in Salem der Freuden |

3' 58" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano

|

LA PETITE

BANDE / Sigiswald Kuijken,

Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I, violoncello da spalla

|

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Jim Kim, violin

I |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Barbara Konrad, violin

II, viola

|

|

|

- Fiona-Emilie

Poupard, violin II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen,

basse de violon |

|

|

- Frank Theuns,

traverso |

|

|

- Bart Coen, recorder |

|

|

- Emiliano Rodolfi,

oboe |

|

|

- Rainer Johanssen,

bassoon |

|

|

- Jean-François

Madeuf, tromba |

|

|

- Benjamin Alard, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - 3/4 December

2012 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25318 - (1 CD) - durata 73'

55" - (p) 2012 (c) 2014 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

”Wachet!

betet! betet!

wachet!”, BWV 70

[Watch ye, pray

ye, watch and

pray], composed in

Leipzig in 1723

for the 26th

Sunday after

Trinity (21

November).

The 26th Sunday

after Trinity is

normally the last

Sunday before Advent

except if Easter is

extremely early, in

which case there are

27 Sundays between

Trinity and Advent.

In very seldom

cases, there are

only 25.

This cantata is one

of the liveliest

ever written by

Bach. It was

originally composed

in 1716 for the

second Sunday in

Advent in Weimar;

this version has not

survived but is

however simple to

reconstruct on the

basis of the Leipzig

version as sung on

this CD. The text

was by Salomon

Franck as is the

case for numerous

Bach cantatas dating

from the Weimar

period.

As already

mentioned, no

cantatas were

performed during

Advent in Leipzig.

Unlike the custom in

Weimar, no cantatas

were performed

during Advent in

Leipzig. Bach had

however undertaken

alterations to this

former Advent

composition from his

Weimar period to

make it suitable for

the 26th Sunday

after Trinity and it

was this version

which was performed

in Leipzig in 1723.

The Gospel reading

for the second

Sunday in Advent is

taken from St. Luke

devoted to the

second coming of

Jesus, the signs

accompanying this

event and warning

Christians to be

prepared for this

through “wachen”

(watching) and “beten”

(praying).

The reading for the

26th Sunday after

Trinity is taken

from St. Matthew on

a virtually

identical theme: the

Day of Last

Judgement. This

permitted the

retention of

Franck’s basic text

and only

necessitated the

compilation of

several (four)

recitatives and a

new chorale movement

concluding the Prima

Pars to be

suitable for its new

purpose.

The Advent cantata

performed in Weimar

consisted of the

movements 1, 3, 5,

8, 10 and 11 of the

Leipzig version

(this Weimar

reconstruction has

been allocated the

BWV No. 70a); the

other movements

(i.e. 2, 4, 6, 7 and

9) are the

additional sections

added in Leipzig.

The 11-movement

version for Leipzig

was performed in two

parts: seven

movements before and

four movements after

the sermon.

The instrumental

scoring specified by

Bach for this

cantata does not

display the

colourful character

of many ‘genuine’

Leipzig

compositions; when

we look to the

hereunder discussed

Weimar Cantata BWV

182, we will see

that the musical

forces were in

principle smaller

than those available

in Leipzig. Here in

the Cantata BWV 70,

the only wind

instruments

alongside the

strings are one tromba

da tirarsi (slide

trumpet) and one

oboe. From the

sources, we can

identifythat a

bassoon was

additionally

required. It is also

certain that the

violins were doubled

in Leipzig and

perhaps also the

bass line in the

strings. Bach

performed this

cantata on a further

occasion in Leipzig

in 1731 in which the

obbligato organ part

in No. 3 (in effect

an ornamented

continuo part) was

allocated to a

violoncello. We have

retained this

version (played here

on the violoncello

da spalla)

although this

violoncello was not

utilised in any

other of the

fragments retained;

it is most likely

that a violinist or

viola player laid

down their

instrument in this

movement and played

the obbligato part

on the small

‘shoulder cello’.

Despite the

relatively

small-scale

instrumental scoring

of this cantata,

Bach has

nevertheless

displayed great

inventiveness and

efficiency. The

fragments added in

Leipzig are a

perfect match to the

earlier composed

Weimar movements.

No. 1, the opening

chorus “Wachet!

betet! betet!

wachet!”

[Watch and pray,

pray and watch]

begins with a 16-bar

instrumental

introduction: we

hear a trumpet motif

twice in succession

(supported by the

strings and oboe)

representing an

appeal to awaken.

This has a specific

connection with the

text from the Gospel

of St. Luke

concerning the

second coming of

Christ: we must

always keep this in

our thoughts and

remain watchful.

(Incidentally, this

motif is also

utilised by Bach in

the second Gavotte

of the Orchestra

Suite No. 1 unisono

in the violins and

violas in which the

motif is allocated a

particularly witty

and decorative

function).

This trumpet motif

in the introduction

leads into an

extremely nimble C

major tutti texture

in lively

semiquavers which

later crop up

repeatedly in the

vocal parts.

At the end of the

introduction, the

trumpet motif is

heard again twice

before the soprano

and alto entries

closely followed by

tenor and bass with

an ascending scale

motif in thirds set

to “wachet!”;

the orchestra then

plays a da capo

of the beginning

which is followed by

two emphatic

homophonic

four-voice settings

of “wachet!”

and a final

polyphonic setting

of this word with

orchestral

accompaniment in

semiquavers.

The tone of the

music changes with

the introduction of

the word “betet!”.

The vocal quartet

sings two powerful

extended notes in

succession on this

word in two distinct

groups above the

continuing figures

in the orchestra and

then continues with

first ascending then

descending

semiquaver figure

sung to “wachet!”.

This produces a

state of confusion

only intensified by

the two wind

instruments which

sustain the long

notes of “betet!”

as if in a double

strand. Bach

continues with these

mechanisms creating

a constant and

effective variety in

texture before

reaching the

dominant key of G

major at which point

the next lines of

text are introduced:

“Seid bereit /

Allezeit” [Be

prepared, night and

day]. Here the

orchestra pauses

briefly, permitting

the singers to call

out the text back

and forth (above a

simple basso

continuo). As the

elements of this

movement have

already been

sufficiently

elucidated, I will

conclude the

detailed description

of the movement at

this point. The

trumpet frequently

fuels the fire of

action with its

motif and the chorus

is concluded with a

powerful tutti.

No. 2, an accompagnato

recitative for the

bass, was

added to the Leipzig

version. The bass

assumes the function

of Vox Dei

(the voice of God),

initially addressing

sinners and

accompanied by

bellicose

instrumental

passages; “Erschrecket,

ihr verstockten

Sünder / Ein Tag

bricht an / vor

dem sich niemand

bergen kann,”

[Oh tremble, all ye

hardened sinners!

The day is near

Which all the wicked

rightly fear.]. He

then turns to the “Auserkorenen”

(chosen few) with

joyful words sung in

serene melismas: “der

Heiland holet euch

/ wenn alles fällt

und bricht / vor

sein erhöhtes

Angesicht / Drum

zaget nicht”

[The Lord will fetch

you thence, When all

in dust is laid,

Before His mighty

presence. Hence: Be

not afraid.].

This is Bach as

composer of

theatrical music: he

clearly also feels

at home within this

sphere – and with

him, so do we.

The ensuing No.

3 (in

principle originally

from the Weimar

version, 1716) is an

aria for alto

with obbligato

violoncello

(see above) to the

words of Salomon

Franck: “Wann

kömmt der Tag an

dem wir ziehen /

aus dem Ägypten

dieser Welt / Ach

lass uns bald aus

Sodom fliehen / eh

uns das Feuer

überfällt”

[When comes the Day

for which we’re

sighing? When bonds

of earth we cease to

bear, Ah! from Sodom

soon let us be

flying, Before the

fire consumes us

there].

The cello (da

spalla)

executes endless

chains of triplet

figures leaping

across extensive

intervals. This is

presumably intended

as a representation

of the problems of

this world. The alto

also contributes to

the tone-colouring

on the words “Feuer”

(fire) and “fliehen”

(flee) with faster

notes. Section B

contains the

following text: “Wacht,

Seelen, auf von

Sicherheit / Und

glaubt, es ist die

letzte Zeit!”

[Awake, ye souls,

from apathy. For

this your final hour

may be.]: we should

awaken out of our

false sense of

security.

The cello plays

ascending arpeggio

figurations: perhaps

the “ausziehen”,

i.e. flight from

Sodom? After a

varied da capo

of the text, the

movement closes with

the initial 12 bars

of the introduction.

No. 4 was

also added to the

Leipzig version: a

brief secco

recitative for

tenor in which

the librettist

describes the human

condition. Our body

holds the spirit

captive (“der

Geist ist willig /

doch das Fleisch ist

schwach” [The

spirit is willing,

Yet the flesh is

weak]).

This is followed by

the Aria No. 5

for soprano

with strings in

unison (violins and

violas) “Lass

der Spötter Zungen

schmähen / es wird

doch und muss

geschehen / dass

wir Jesum werden

sehen” [Though

the mocking tongues

revile us, They

cannot from faith

beguile us, That one

day our souls we

render]. The

“mocking tongues”

are depicted in

rapid instrumental

figures which are

occasionally taken

up by the bass. The

aria contains

detailed notation of

how the unisono

passages can be

varied through the

involvement of

additional voices or

a reduced scoring:

this is a rare

feature. An

extremely positive

attitude attempts to

overcome the doubt

as expressed in the

previous text

passages.

Like No. 4, No.

6 is a brief secco

recitative for

tenor which

continues on a

positive note: God

will hold his

protecting hand over

his servants and

place them in

paradise.

The first part of

the cantata in the

Leipzig version

concludes in joyful

triple time with a

simple setting of a

chorale verse

(No. 7) taken

from a chorale

dating from 1620 (“Freu

dich sehr, o meine

Seele”

[Rejoice greatly, O

my soul]). Christ

“calls away the

spirits from this

vale of tears (“ruft

die Seele aus

diesem Jammertal”).

They will be

bestowed eternal joy

and will rejoice

with the angels.

At this point, the

sermon was

presumably given.

The Seconda Pars

of the cantata

begins with the Aria

(No. 8) for tenor

with strings and

oboe: “Hebt

euer Haupt empor /

und seid getrost,

ihr Frommen”

[Hold ye your heads

now high, And be

assured, ye

faithful]. This

movement in G major

is an aria of simple

beauty and long

remains in our

hearts . The tenor

and instrumental

upper voices (1st

violin in unison

with the oboe)

maintain a constant

dialogue above the

regular pace of the

middle voices and

continuo.

The ensuing striking

accompagnato

recitative (No. 9)

for bass and

instrumental

ensemble

(excluding the oboe)

was newly composed

in Leipzig. The

(unknown) librettist

reiterates how man

could be filled with

“doubt, fear and

terror” (“Zweifel,

Furcht und

Schrecken”) on

the great Day of

Judgement. Bach

utilises numerous

theatrical

interjections in the

string parts

providing a further

illustration of the

terrifying images of

the Day of

Judgement. He also

had the wonderful

idea of including

the chorale melody “Es

ist gewisslich an

der Zeit” [It

is certainly time]

on the trumpet

(without a vocal

part!) which soars

high above the

raging string parts.

The congregation

would definitely

have been familiar

with this melody and

understood its

associations – to a

greater degree than

we do today.

Suddenly, a

completely different

atmosphere is

created: man should

have no fear as “The

Saviour cannot hide

His deep compassion.

He pities now my

lot,” (“der

Heiland kann sein

Herze nicht

verhehlen, so

von Erbarmen

bricht”). On

the word

“compassion” (“Erbarmen”)

we hear plaintive

chromaticism in the

vocal parts and

“sighing” figures in

the strings up to

the end of the

recitative. The

movement concludes

with the text “Wohlan,

so ende ich mit

Freuden meinen

Lauf” [‘Tis

well! when comes the

Day with joy will I

away]; on the word “Freuden”,

Bach writes an

extended vocalise

for the bass as the

sighing motifs on

the strings

gradually fade away.

The bass is

also allotted the

next Aria (No.

10 with strings

and trumpet solo).

This movement

characterised by

unbelievable

contrasts is divided

into three sections:

first of all, the

bass sings a Molt’Adagio

in triple time

accompanied only by

continuo: “Seligster

Erquickungstag /

Führe mich zu

deinen Zimmern!”

[Hail, thou day when

I may dwell High

above with God in

Heaven.]. This is

one of Bach’s most

lyrical inventions

in which the musical

concept bewitches

the listeners: we

are overwhelmed by

an almost celestial

tranquillity. This

is however

interrupted without

any transition and

the librettist (S.

Franck) focuses our

attention towards

the end of time: “Schalle,

knalle, letzter

Schlag / Welt und

Himmel, geht zu

Trümmern!”

[Crash and crackle,

roar and knell, When

creation meets

destruction]. Here

the strings and

trumpet are again

permitted to run

wild. The final

emphatic orchestral

chord is however not

a genuine

conclusion, but

leads into an

extended slightly

dissonant chord with

the seventh in the

basso continuo,

capsizing the effect

into an atmosphere

of astonishment. The

bass now sings in

Adagio: “Jesus

führet mich zur

Stille / an den

Ort da Lust die

Fülle” [Jesus

leads me far from

sadness, There with

Him where all is

gladness.]. A state

of mystical peace

has now been

achieved, the music

returns to the

initial Molt’Adagio

which concludes this

movement.

The cantata ends

with the final chorale

(No. 11), the

fifth verse of the

hymn ‘Meinen

Jesus lass ich

nicht’ [I

shall not let my

Jesus go] by

Christian Keymann

(1658): “Nicht

nach Welt, nach

Himmel nicht / Meine

Seele wünscht und

sehnet” [Not

for Heaven nor the

world Is my weary

spirit yearning].

The fourpart vocal

harmonisation (with

oboe and trumpet

doubling the

soprano) is

accompanied by the

independent voices

of the three upper

string parts, making

a total of seven

voices

simultaneously! I

leave the listeners

to decide

independently on the

significance of the

number seven. Bach

must however have

had a specific

intention in this

scoring, as he would

otherwise have

composed this choral

in a customary

four-part setting.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation:

Lindsay

Chalmers-Gerbracht

”Es

ist das Heil uns

kommen her”, BWV 9

[Now is to us

salvation come]

This cantata dates

from the period

1732-1735 and was

composed for the 6th

Sunday after Trinity

in Leipzig as one of

the late choral

cantatas. The text

has been taken from

a 14-verse hymn by

Paul Speratus dating

from 1523 which had

become an integral

part of this

particular Sunday

service: the text is

based on the Gospel

reading from the

Sermon on the Mount

(Matthew 5, 20.26)

which describes the

Christian concept of

justice in contrast

to the Pharisaic

tradition. The two

final verses of this

hymn are a

paraphrase of the

Lord’s Prayer, but

these were not

selected for the

cantata by whoever

compiled the text.

The librettist

combined the first

twelve consecutive

verses divided into

seven individual

sections which in

certain places

display traces of

reworking and

editing:

- No. 1 (coro) is

the unaltered first

verse by Speratus,

1523;

- No. 2 (secco

recitative),

reworking of verses

2 – 3 – 4

- No. 3 (aria), free

fantasy on the final

idea of the previous

recitative;

- No. 4 (secco

recitative),

reworking of verses

5 – 6 – 7;

- No. 5 (duet aria),

reworking of verses

8;

- No. 6 (secco

recitative),

reworking of verses

9 – 10 – 11;

- No. 7 (simple

chorale) is verse 12

in its original

form.

This method of

‘reworking’ had been

utilised in many of

the early choral

cantatas, mostly

with the retention

of the first and

last verses in their

original form.

The three secco

recitatives are

allocated to the

bass who provides a

unified strand

throughout the

entire work: a

self-contained train

of thought almost in

the manner of a

sermon.

In the first

version, the organ

did not play in the

movements 2, 3, 4

and 6, probably due

to tuning problems:

at times, the music

modulates into very

rarely used keys

which would sound

overtly dissonant on

the contemporary

organ tuning of the

time. The scoring of

this Leipzig cantata

is fairly modest:

alongside the four

singers, the

instrumental forces

are limited to

strings, transverse

flute and oboe

d’amore.

No. 1 Coro

(transverse flute,

oboe d’amore,

strings, SATB and

basso continuo)

Here is a summary of

the content of the

first chorale verse:

Salvation came to

us by grace and

purest favour;

it is not so much

good works that

help us, but

our faith

directed towards

Jesus: he did much

for us and

is the true

intercessor.

The cantata is

written in E major,

a transparent key

without violence or

demonstrative force.

The entire texture

of the work is

coloured by its key.

A 24-bar

introduction

precedes the first

entry of the voices.

The woodwind

instruments play a

principal role,

occasionally

combined with the

two violini

primi; the

basso continuo

provides a regular

rhythmic scaffolding

throughout the

entire movement. The

second violin and

viola primarily

fulfil a filling-out

function in this

extended movement.

The choral melody is

sung by the soprano

in extended notes

with no instrumental

doubling. Under this

melodic line, as

frequently

encountered in

Bach’s music, the

other three vocal

lines form a freely

developed

contrapuntal texture

in which the

imitation is largely

based on a single

principal motif. The

seven lines of the

chorale verse are

divided into blocks

each interspersed by

instrumental

interludes which

also display a

certain similarity

to each other. This

lends the movement

length and

continuity with an

almost intoxicating

effect. Particularly

poignant is the

brief section in the

penultimate verse “Der

hat gnug für uns

all getan”

[Who hath enough

done for us all]

where the three

lower voice parts

reinforced by viola

and basso continuo

sing each individual

syllable incisively

in equally short

notes. At this

point, Bach was

apparently making an

extra effort to

engage the

listeners’ interest,

enabling them to

assimilate each word

of the text!

I interpret the

selection of the two

woodwind instruments

which dominate the

work with their

dialogue as

representing the

constant activity of

the Holy Spirit, the

Spiritus,

which is inherent in

Christ’s grace and

favour. Spiritus

also means breath,

i.e. also tender

care; this is

reminiscent of the

aria “Aus Liebe

will mein Heiland

sterben” [Out

of love my saviour

iswilling to die] in

the St. Matthew

Passion in which the

soprano is

exclusively

accompanied by wind

instruments. Is the

fact that wind

instruments

transform breath

into musical sound

not their most

profoundly

attractive

characteristic?

The next movement No.

2 is the first

secco recitative

for the bass.

We must consider all

three bass

recitatives as a

single train of

thought interrupted

twice by the arias

(Nos. 3 and 5). One

could think that

Bach was here

lending the bass the

authority of a

catechetical

instructor

(comparable with the

Vox Dei which

is almost always

assigned to the

bass). The first

recitative tells us

that man is never

capable of

withstanding sin,

even though God gave

him laws (the rules

of the Old

Testament) and a

certain natural but

imperfect notion of

good and evil. In

this recitative, the

declamation of the

bass is frequently

accompanied by

dissonant harmonies

reinforced in the

basso continuo.

Movement No. 3

(Aria for tenor,

with obbligato

violin and B.c.)

is a commentary on

the previous

concepts: “Wir

waren schon zu

tief gesunken /

Der Abgrund

schluckt uns

völlig ein”

[We were ere then

too deeply fallen,

The chasm sucked us

fully down].

The aria is notated

in the rare time

signature of 12/16

and begins with a

twelve-bar

introduction with

violin and basso

continuo in which

Bach introduces the

thematic content of

this movement: the “tief

gesunken”

[deeply fallen] is

represented by a

long descending

scale in legato

accompanied by a

simple bass-line.

The violin

additionally

introduces a series

of triplet motifs

which repeatedly

incorporate a

substantial

descending leap,

frequently as a

lamentation (once

again the “sinking”

concept). The

instrumental bass is

initially also

allocated a few

triplet figures. At

the entry of the

vocal line, the

tenor adopts the

sinking motif of the

violin, both voices

entering into an

intense dialogue in

which the basso

continuo becomes

increasingly

involved. After a

twelve-bar interlude

(a variant of the

introduction), we

hear the B section

of the text (the

last three verses

from “Die Tiefe

drohte schon den

Tod” [The deep

then threatened us

with death]) in

which the concept of

“threat” is

expressed by a vocal

line with an

ascending tendency

in progressive

intensification; the

descending figure

remains omnipresent.

The three-part

texture now displays

all kinds of

melismas; this

movement is unique

and truly

awe-inspiring.

The bass

takes over once more

in No. 4 (secco

recitative):

the law had to be

fulfilled and

therefore Jesus came

down to us. He

“stilled his

father’s wrath” (seines

Vaters Zorn

gestillt)

through his own

“guiltless dying” (“unschuldig

Sterben”). For

this reason,

Christians must

trust in Jesus: they

will achieve entry

to heaven if they

recognise the true

faith and embrace

Jesus firmly. This

text is like the

previous recitative

given a distinct

rhetorical slant

with powerful

harmonies; in the

last verse, “und

fest um Jesu Armen

schlingt” [And

firmly Jesus’ arms

embrace], Bach

writes “arioso”:

the secco style is

abandoned and a

two-voice texture is

created in a

measured tempo in

which the two

melodic lines are

indeed “entwined”.

This instructional

recitative is now

interrupted by the Duet

(No. 5, soprano

and alto with

both wind

instruments and

basso continuo)

with the text “Herr,

du siehst statt

guter Werke / auf

des Herzens Glaubensstärke”

[Lord, thou look’st

past our good

labors, To the

heart’s believing

power]. The fact

that faith is more

important than good

works has already

been elucidated in

the opening chorus.

This is the

leitmotif which

recurs at this

point. The invisible

internal process of

faith is beautifully

captured by the two

wind instruments:

the process of

breathing, i.e. the

Spiritus, is

indeed also

invisible and has an

effect on a profound

level.

In the introduction

to section A, the

flute and oboe

d’amore hold their

own dialogue; this

passage contains 24

bars just as the

introduction to No.

1. The first aria

has an introduction

consisting of 12

bars (perhaps there

is a concealed

significance in the

number

combinations?). But

this is not all: in

each section, flute

and oboe d’amore

play in a strict

canon at the lower

fifth (a bar apart

and the oboe a fifth

below the flute).

Then the vocal

soloists enter, also

singing the first

three verses in a

strict canon at the

fifth whereas the

wind instruments

continue in their

own strict

imitation, now at

the upper fourth. In

bar 44, the woodwind

dialogue resumes (at

this point with less

strict imitation)

for an interlude of

a mere four bars,

before soprano and

alto re-enter, in

canon as before and

alongside the flute

and oboe. By this

point, a fourvoice

texture containing

two independent

quasi-strict canons

running

simultaneously has

emerged, accompanied

discretely by the

basso continuo.

Following an

extended interlude

(again 24 bars!),

section B commences;

here Bach alters his

compositional style:

in these verses, the

wind instruments now

merely accompany the

vocal lines (with

some ornamentation)

“Nur der Glaube

macht gerecht /

alles and’re

ist zu schlecht”

[Nought but faith

dost thou accept.

Nought but faith

shall justify]. The

fact that Bach

reduces the

complicated

contrapuntal

fourvoice texture

created by the four

soloists (the

uninvolved basso

continuo only plays

a supporting role)

to a purely two-part

texture (through

instrumental

doubling) could have

been suggested to

him by the text: “Nur

der Glaube macht gerecht”,

i.e. it ‘simplifies’

and ‘clarifies’.

Incidentally, this

doubled canon in

section B is also in

strict form for the

first twelve bars,

but is slightly

freer in the ensuing

bars.

Section A is then

repeated in

conclusion. In this

outstanding duet

(actually a ‘double

duet’!), the general

impression is of

freely flowing and

natural music

despite the fact

that Bach has in

fact utilised an

extremely strict but

simultaneously

enigmatic structure.

The bass now

rounds off his train

of thoughts (secco

recitative, No. 6).

We hear a sort of

recapitulation:

according to the

words of the

Gospels, we should

always be joyful and

can depend on Jesus

Christ. We do not

know how long our

time will be here on

earth, but we can

depend on his

benevolence; he will

not play a game of

deceit, but knows

what is good for us.

As in the previous

recitatives, the

harmony is always

dictated by the

affect of the text

and, in my opinion,

even goes a step

further than the

occasionally ominous

words.

Now we come to the

original twelfth

verse of the hymn

dating from 1523 (No.

7, Chorale),

again focusing on

the fundamental

concept that we must

trust in God, even

if we do not always

understand Him and

are sometimes

inclined to negate

Him. The chorale is

sung in a simple

four-voice texture.

A highlight is the

setting of the word

“grauen”

(horror) for which

Bach could not

resist giving a

final harmonic touch

with a madrigal

flavour.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

"“Himmelskönig,

sei willkommen”",

BWV 185

Bach composed this

cantata in Weimar in

1714 for Palm Sunday

which that year fell

on 25 March, on the

same date as the

feast of the

Annunciation [Annunciatio]

(also occurring nine

months before

Christmas). He

subsequently

organised a second

performance of the

cantata with certain

alterations in

Leipzig under the

title Annunciatio

Cantata;

although no music

was permitted in

church services in

Leipzig during Lent,

an exception was

made for the Feast

of the Assumption,

even if 25 March

fell within the

‘silent period’

(which was not

observed in Weimar).

On this recording,

we perform the

original version

composed in Weimar

in 1714. This was

the first cantata

composed by the

29-year-old Bach on

his appointment as

concert master at

the Weimar Court (on

2 March 1714). His

duties included the

performance of a new

cantata

once a month.

The text was

compiled by Salomon

Franck (1659-1725),

one of the leading

cantata poets of his

time and also the

court poet in

Weimar. Bach took

particular pleasure

in setting his texts

during his period in

Weimar (and

occasionally also in

his subsequent

career).

As the castle chapel

in Weimar was

relatively small,

there was only space

for a modest musical

ensemble: in his

Weimar cantatas Bach

employs four singers

and normally an

instrumental group

consisting of two

violins, two violas,

a stringed bass

instrument (often

designated as “Violoncello”)

and organ (as for

example in BWV 54 Widerstehe

doch der Sünde

[Stand firm against

Sin]). In the

Cantata BWV 182

however, instead of

two violins, we hear

a recorder partnered

with a violin. The

string bass line is

here also undertaken

by a violoncello

(da spalla

i.e. in my opinion)

a shoulder cello.

The recorder

stipulated by Bach

in this work is

tuned to the low

chamber pitch (Kammerton,

A = ca. 392 Hz) as

was customary for

instruments

constructed in the

contemporary French

tradition which had

also extended into

Germany during the

late seventeenth

century. This means

that the recorder is

tuned a minor third

lower than the other

instruments which

were tuned to the

high choral pitch

utilised in the

Weimar chapel

including the organ

(Chorton, A =

465 Hz). This

permits additional

notes to be played

in the lower range

of the reorder which

Bach exploits on a

number of occasions.

If the cantata is

performed as

stipulated in Bach’s

original Weimar

score, the

simultaneous

utilisation of the

two pitches is

necessary. In

contrast, the later

version for Leipzig

was performed in

adaptation to the

local circumstances:

the Leipzig

orchestra played a

whole tone lower

than the organ (i.e.

A = 415),

necessitating

adjustments to the

recorder part in the

Weimar score.

The Gospel reading

for Palm Sunday is

taken from St

Matthew (21, 1-9): Jesus

entering Jerusalem.

Jesus enters the

city riding on a

donkey surrounded by

his disciples. I

consider the image

of Jesus as a ‘king’

arriving on a donkey

to be most likely an

interpretation post

facto, but it

nevertheless

elucidates its

essential element.

Is the donkey not

the means of

transport used by

the poor? This image

therefore makes

direct reference to

the inner world of

this spiritual king

(who is neither rich

nor worldly);

incidentally, the

Flight into Egypt

also took place on

the back of a

donkey.

No. 1 Sonata:

The instrumental

introduction neatly

illustrates the

content of the Bible

reading: the King of

Heaven arrives on

the back of a donkey

with little pomp and

is nonetheless a

king. The music

reflects this

unexpected humility

despite its grandeur

with minimal

orchestration. The

familiar dotted

rhythms of an

overture which

normally resound in

full orchestration

in celebration of a

festive occasion are

played here only on

recorder and violin;

the festive

atmosphere is merely

alluded to by a pair

of delicate

instruments. The

accompanying pulsing

pizzicato in the

other instrumental

parts presumably

suggests the firm

steps. Towards the

end of the

introduction, the

accompanying strings

play an extended

sustained note (the

arrival?);

ultimately they also

join in the dotted

rhythms; the

character of the

event is perfectly

captured despite the

limited resources.

No. 2 Chorus

This movement more

resembling a

madrigalesque

fragment than a

monumental structure

is divided into two

brief sections.

In the A section (“Himmelskönig,

sei willkommen /

Lass auch uns dein

Zion sein!””

[King of Heaven,

ever welcome, Make

our hearts Thy

dwelling place!] ),

the text is

presented by the

four singers

successively in

imitation (fugato)

accompanied by basso

continuo (beginning

with the soprano and

progressing down to

the bass). This is

immediately repeated

with the strings

doubling the vocal

lines. After the

final (‘tutti’) bass

entry, the recorder

enters with the

theme as the fifth

voice but not

doubling the vocal

line and thereby

effecting the

transition to the

next section (2nd

verse). Here the

text “Lass auch

uns dein Zion sein”

is also presented on

a new motif by all

voices entering in

imitation, this time

beginning with the

bass and ending with

the soprano (with

instrumental

doubling). In this fugato,

the recorder also

enters as the fifth

voice before the

motif is combined in

fugato in the

four vocal parts

descending from

soprano to bass.

Following this

second fugato,

Bach concludes the A

section with a

homophonic repeat of

the text of both

verses divided

clearly into

separate elements by

intermittent

answering phrases on

the strings. The

recorder and violin

additionally play in

dialogue utilising

the second motif.

Without doubt,

Bach’s selection of

entry sequences in

this A section is a

clear example of

‘tone painting’. At

the beginning (“Himmelskönig

sei willkommen”),

we hear the entries

in descending order

(the King descends

from heaven), and

then the order is

reversed from bottom

to top in the verse

“Lass auch uns

dein Zion sein”

pointing the way up

to heaven (let us

also partake of

heaven!) and then

back down to earth

where we are

actually based

during our lifespan.

Finally, the entire

depicted image is

consolidated in the

homophonic

conclusion of this

section.

The B section also

begins in a

homophonic texture

in the vocal quartet

with the words “Komm

herein” [bide

with us]. The

instruments answer

with the initial

motif in the

recorder part from

section A. The next

verse “Du hast

uns das Herz

genommen” [Our

hearts are in your

keeping] is

presented above a

protracted pedal

note, further

extended in a

fourvoice canon with

the initial verse Himmelskönig,

sei willkommen

and augmented by

additional

instrumental entries

without text in the

upper strings,

recorder and

violoncello. On this

last cello entry,

the soprano

re-enters with the

second verse Lass

uns doch dein Zion

sein which is then

immediately

presented in fugato

by alto, tenor and

bass. At this point,

the same procedure

as at the beginning

of the B section is

repeated, but this

time a whole tone

lower: Komm

herein is sung

in a homophonic

texture followed by

the pedal note for Du

hast uns das Herz

genommen /

Himmelskönig sei

willkommen.

The B section

concludes with a

brief piano passage

in which the line is

repeated in a

homophonic

structure;

simultaneously, the

recorder adds a

swift ascending

figure up to its

highest note: the

heavenly Zion!

Section A is then

repeated in full.

This chorus has a

remarkably

concentrated

structure: it

probably takes far

longer to read the

above description of

the compositional

process than to

actually listen to

this movement. This

is frequently the

case with Bach: we

can pinpoint his

working methods

which provide a

fascinating subject

for research, but

the music itself

passes by so swiftly

with exceptional

intensity in a mere

few moments.

The next movement is

a Recitative

(No. 3) for bass

who undertakes the

role of Vox Dei

as is so often the

case with Bach: the

text originates from

Psalm 40, verses 8-9

(“Siehe, ich

komme, im Buch ist

von mir

geschrieben.

Deinen Willen,

mein Gott,

tue ich

gerne“ [Lo, I

come, I am with you,

for so it is written

of Me: I delight O

my Lord, my God, my

God, I delight to do

Thy will]). From the

words Deinen

Willen, the

secco recitative is

superseded by an

ariosa dialogue

marked Andante

between the bass

singer and the basso

continuo with a

walking rhythm

(perhaps evoking the

“Komme“ from

the beginning of the

text?).

In the ensuing Aria

(No. 4) for bass

and strings

(without recorder),

the librettist

provides a

commentary for the

previous Psalm text:

“Starkes Lieben /

das dich,

großer Gottessohn

/ von dem Thron /

deiner Herrlichkeit

getrieben”

[Love unending,

‘Twas for love that

God’s own Son came

to us, Down from His

exalted station. The

King of Heaven has

not come down to

rule as a secular

monarch.

In this movement,

the violin enters

into a permanent

dialogue with the

bass soloist; the

other strings

illustrate “Getrieben

werden”, the

sense of being

driven, through

quaver runs filling

out the harmony in a

swift Andante.

On a few occasions,

the instrumental

bass line imitates

the principal theme

augmented by the two

violas, creating a

three-voice texture

of thematic motifs.

This is followed by

a further Aria

(No. 5)

without a preceding

recitative scored

for alto solo,

recorder and basso

continuo. The

text continues where

the words of the

previous movement

left off, urging

Christians to devote

themselves in their

faith entirely to

the King of Heaven:

“Leget euch dem

Heiland unter /

Herzen, die ihr

christlich seid”

[Bow your heads

before your Saviour,

Ever keep as pure as

He]. The Aria is

marked Largo (and

the second section Andante,

although the tempo

cannot be very

different).

The recorder which

was absent from the

preceding aria now

assumes a solo role.

The recorder is

frequently utilised

to illustrate the

theme of love, but

is additionally

associated with

sorrow, pain and

death. And all this

is required in this

movement. The aria

discusses life seen

as a whole, i.e.

also including pain

and death. The

lower-pitched

(French) recorder is

exploited to its

full tonal range in

this aria. The

principal motif has

clearly evolved out

of the image

contained in the

text: the line “leget

euch unter”

calls out for

descending movement

with a sinking motif

which recurs

repeatedly in the

two principal voices

of alto and

recorder. The basso

continuo accompanies

in a simple,

regularly paced

line. In section B (“Tragt

ein unbeflecktes

Kleid” [wear

an unspotted robe]),

a new motif without

descending movement

is introduced in the

vocal line; the

recorder however

retains the initial

theme, permitting

both sections of the

text to be

correspondingly

intricately

entwined. A notable

feature is the long

note on “Leget”

depicting immobility

and protraction.

A third Aria

(No. 6) for tenor

and basso continuo

(violoncello and

organ) also follows

without a preceding

recitative: “Jesu,

lass durch Wohl

und Weh /

mich auch mit dir

ziehen! / Schreit

die Welt nur „Kreuzige!”

/ so lass mich

nicht fliehen”

[Jesus, Lord,

through weal and

woe, Keep me ever by

thee. When the world

shrieks Crucify! Let

me never, let me not

deny Thee]. We

immediately

recognise where Bach

has found his

principal material

for the aria in the

basso continuo

introduction: the “Fliehen”

[fleeing] is

represented in swift

semiquaver runs on

cello and organ;

this agitation is

only interrupted at

a few points and

then immediately

resumed. The

agitation stands in

great contrast to

the preceding aria.

Here it is man

speaking who must

follow his path

“through weal and

woe” (“durch Wohl

und Weh”),

fortifying himself

during his

tribulations through

the example of Jesus

Christ. The final

lines have the

following text: “Herr,

vor deinem

Kreuzpanier / Kron

und Palmen find

ich hier”,

which can be

interpreted as

“salvation can be

found by imitating

Christ”.

When these three

consecutive arias

are considered as a

whole, the clearly

imaginative

diversity of the

Baroque stands out

with its extreme and

effective contrasts:

this is Johann

Sebastian Bach again

at work as both

painter and

architect.

No. 7 (Chorale)

is a choral

arrangement in the

style of the late

seventeenth century

à la Pachelbel. The

text (set to a

melody dating back

to the sixteenth

century) was written

by Paul Stockmann

(the 33rd verse of a

church hymn

originating in

1633). He relates

that the suffering

of Christians has

been overcome by the

passion of Jesus and

that they can look

forward to a place

in heaven after

death.

The soprano, doubled

by the recorder and

violin, sings the

choral melody in

extended notes; the

eight verses are

distinctly separated

from one another.

The three lower

voices develop an

intense contrapuntal

texture in which the

motifs of the

following verses are

frequently announced

in shorter

note-values and in

decorated form. The

verses 1, 3, 5, 7

and 8 are thereby

clearly recognisable

in advance in the

lower vocal parts.

The cantata

concludes with the Chorus

No. 8 “So

lasset uns gehen

im Salem der

Freuden” [So

let us then hasten

to Salem rejoicing].

This is an innately

joyful movement in

6/8 time; we

re-encounter the

initial theme almost

unchanged at a later

point in Leipzig in

the opening movement

of the Epiphany

Cantata BWV 5 “Sie

werden aus Saba

alle kommen”

[They will all come

forth out of Sheba]

but incorporated in

a much more festive

and large-scale

format.

Recorder,

violoncello and

(only a single!)

violin begin the

movement as a solo

trio; the violas and

basso continuo (the

organ only plays at

this point) answer

this beginning in

the ensuing tutti

with the theme in

the bass. This is

followed by a

section in fugato

style with the verse

“So lasset uns

gehen” sung by

the four singers

from top to bottom

(SATB) above the

continuo

accompaniment. Three

additional entries

follow on from the

vocal entries played

by the recorder, the

violin (doubled in

the soprano) and

finally the two

middle instrumental

voices (violas) with

the cello at the

octave. The next

verse “Begleitet

den König in

Lieben und Leiden”

[Accompany the King

in love and sorrows]

follows with a motif

in the accompanying

continuo bass line

which has clearly

been adopted from

the principal theme:

this motif is then

taken up by the

soprano. The da

capo of the

instrumental

introduction rounds

off section A.

Section B “Er

gehet voran”

[He goes before] is

led by the

vocalists: here in a

literal

interpretation of

the text, the bass

hastens with the

words “er gehet

voran”. This

could not be

illustrated more

simply: a descending

motif subsequently

appearing in

imitation represents

Christ descending to

earth. This is

contrasted by a

mirrored

counterpoint in the

recorder part (i.e.

ascending)

which recalls the

initial theme. The

simultaneous

utilisation of

ascending and

descending lines

lucidly illustrates

the image in the

text “eröffnen,

breit aufmachen

der Bahn” [He

goes before and

opens the way]. A

further conspicuous

feature in section B

are the long held

notes on the word “Bahn”

[way] in all

voices (including

the instrumental

parts without

text!). The cantata

concludes with a da

capo of

section A. Despite

its modest

instrumental and

vocal forces, this

work possesses an

extremely

concentrated and

monumental structure

which is rich in

imaginative tonal

images.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation:

Lindsay

Chalmers-Gerbracht,

Christopher

Cartwright

|

|