|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25317 - (p) 2005-12

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25317 - (p) 2005-12 - rectus

|

|

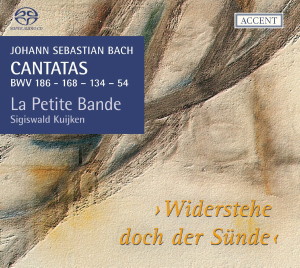

CANTATAS -

Volume 17

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

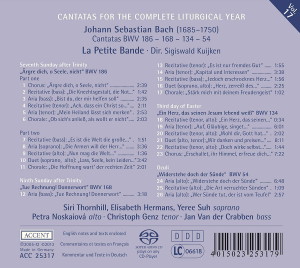

| 7. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Ärgre dich, o

Seele, nicht", BWV 186 |

|

26' 49" |

|

| Part one |

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Ärgre dich, o Seele,

nicht |

2'

38"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Die

Knechtsgestalt, die Not, der Mangel |

1' 42" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Bist du, der mir

helfen soll |

2' 34" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Ach, dass

ein Christ so sehr |

2' 10" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Mein Heiland

lässt sich merken |

2' 53" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ob sich's anließ, als

wollt er nicht |

2' 03" |

|

|

| Part two |

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Es ist die

Welt die große Wüstenei |

1' 50" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Die Armen

will der Herr umarmen |

3' 35" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Nun mag

die Welt mit ihrer Lust vergehen |

1' 36" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, alto):

Lass, Seele, kein Leiden |

3' 42" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Die Hoffnung wart'

der rechten Zeit |

2' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Tue Rechnung!

Donnerwort", BWV 168 |

|

14' 27" |

|

| -

Aria (bass): Tue Rechnung!

Donnerwort |

3' 17" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Es ist

nur fremdes Gut |

1' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Kapital und

Interessen |

3' 37" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Jedoch,

erschrocknes Herz, leb und verzage

nicht |

1' 55" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, alto):

Herz, zerreiß des Mammons Kette |

2' 24" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Stärk mich mit deinem

Freudengeist |

1' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Osterfesttag |

|

|

|

| "Ein Herz, das

seinen Jesum lebend weiß", BWV

134 |

|

25' 55" |

|

| -

Recitative (tenor, alto):

Ein Herz, das seinen Jesum lebend

weiß |

0' 33" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Auf, Gläubige,

singet die lieblichen Lieder |

6' 01" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor, alto):

Wohl dir, Gott hat an dich gedacht |

2' 02" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (alto, tenor):

Wir danken und preisen... |

8' 11" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor, alto):

Doch wirke selbst den Dank in unserm

Munde |

1' 43" |

|

|

| - Chorus: Erschallet, ihr

Himmel, erfreue dich, Erde |

7' 25" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oculi |

|

|

|

| "Widerstehe doch

der Sünde", BWV 54 |

|

10' 52" |

|

| -

Aria (alto): Widerstehe doch

der Sünde |

6' 47" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Die Art

verruchter Sünden |

1' 08" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Wer Sünde tut,

der ist vom Teufel |

2' 57" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

BWV 186

|

BWV 168 |

BWV 134 |

BWV 54 |

|

Siri Thornhill,

soprano

|

Elisabeth

Hermans, soprano

|

Yeree

Suh, soprano

|

Petra

Noskaiová, alto |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

|

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

Christoph Genz,

tenor |

Christoph Genz,

tenor |

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LA PETITE BANDE / Sigiswald Kuijken, Direction |

|

| - Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| - Rachael Beesley,

violin I |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

I |

- Annelies Decock,

violin I |

- Jim Kim, violin

I |

|

| - Katharina Wulf, violin

I |

- Sara Kuijken, violin

II |

- Ann Cnop, violin

II |

- Barbara Konrad, violin

II |

|

| - Sara Kuijken, violin

II |

- Giulio D'Alessio,

violin II |

- Masanobu Tokura,

violin II

|

- Fiona-Émilie

Poupard, violin II

|

|

| - Giulio D'Alessio,

violin II |

- Marleen Thiers,

viola |

- Sara Kuijken, viola |

- Marleen Thiers,

viola |

|

| - Marleen Thiers, viola |

- Koji Takahasji,

basse de violon |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violoncello da spalla

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

- Inka Döring, basse

de violon

|

- Eve François,

basse de violon |

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

- Benjamin Alard, organ |

|

| - Koji Takahasji, basse

de violon |

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe, oboe d'amore

|

- Michel Boulanger,

basse de violon |

|

|

| - Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe |

- Yann Miriel, oboe,

oboe d'amore |

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe |

|

|

| - Daniel Dehais, oboe

|

- Ewald Demeyere,

organ |

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe |

|

|

- Ann Vanlancker, oboe

(Taille)

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ |

|

|

| - Rainer Johannsen,

bassoon |

|

|

|

|

| - Benjamin Alard, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

-

s'Gravenwezel Castle (Belgium) -

July 2005 - (BWV 186)

- Predikherenkerk, Leuven

(Belgium) - Sempember 2005 - (BWV

168)

- Academiezaal, Sint Truiden

(Belgium) - April 2009 - (BWV 134)

- Predikherenkerk, Leuven

(Belgium) - 3/4 December 2012 -

(BWV 54)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25317 - (1 CD) - durata 77'

51" - (p) 2005-12 (c) 2013 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

“Ärgre

dich, o Seele,

nicht,”, BWV 186

for the seventh

Sunday after

Trinity.

A. Dürr describes in

detail how this

cantata for the 11th

July 1723 came about

from an original

Weimar Advent

Cantata of 1716,

that is during

Bach’s first year in

Leipzig.

Because all the

recitatives and the

chorale, which

closes both parts,

were newly added, a

two-part cantata of

more substantial

dimensions was

created.

The aria texts were

adapted, where

necessary, to the

new requirements.

From the original

Weimar text of

Salomon Franck only

the opening chorus

and the aria no. 8

“Die armen will der

Herr umarmen” (The

Lord will embrace

the poor) remain.

The text of the

chorales (nos. 6 and

11) is from the hymn

“Es ist das Heil uns

kommen her” (It is

our salvation

approaching) (P.

Speratus 1523). The

author/compiler of

these various old

and newer parts is

unknown. It is

conceivable that

Bach himself made a

contribution in such

cases.

The first half of

the Cantata (before

the sermon) begins

with an impressive Chorus

(No. 1): The

“Ärgre dich, o

Seele, nicht” (Fret

thee not, O my soul)

is sung after the

oppressive harmony

of the instrumental

introduction by the

four singers, and is

immediately imitated

by the wind

instruments (oboe

and oboe da caccia).

The next three lines

are then set in a

dense Fugato. This

double structure is

repeated in another

key and form, which

leads back to the G

minor of the

beginning.

Noteworthy is the

constant repetition,

in the basso

continuo, of an

ascending

arpeggio-figure of

four quavers each

time. It could be an

expression of

agitation, of the

fretting, how the

mind tries to make

its conflicts known

... The text of this

chorus is calling us

to accept the

Mystery of the

Incarnation of God

in its paradoxical

incomprehensibility:

God, the Supreme

Light disguised as a

servant!

In the following Bass

Recitative (No. 2)

the meaning of these

lines is made clear:

not only does Christ

want to be poor and

ordinary – the

Christian should

also strive to be

like that, but at

the same time

discourage his

egotism.

The Aria

“Bist du, der mir

helfen soll” (Art

thou the one who

will help me)” for

Bass and basso

continuo (No. 3)

is like a courante,

as we often find in

Bach. Is it an

allusion to the

content of the text

“Eilst du nicht, mir

bei zu stehen?”

(Dost thou not

hasten, to stand by

me?) in the second

line of the aria?

The text, set in the

active trochee

metre, implores us

here to seek all of

God’s help.

Our

faint-heartedness

and insularity are

vividly presented in

the succeeding Tenor

Recitative (No. 4),

and in a lyrical

arioso section

Christ’s friendship

opposes it, which

will stand by us in

our sorrow.

This central thought

is developed further

in the following Aria

(No. 5) “Mein

Heiland lässt sich

merken” (My Saviour

lets Himself be

seen). The violins,

in unison with the

first oboe,

accompany the entry

of the soloist and

say farewell to him

at the end in just

as flowery a manner.

A picture of the

‘works of grace’ in

the second line? On

the words “den

schwachen Geist zu

lehren / den matten

Leib zu nähren” (To

teach the weak mind

/ to nourish the

weary body) the high

instruments cease

their activity and

just play a weak

held note.

The Closing

Chorale of

this first part (No.

6) is

surrounded by

concertante

instrumental

passages, which,

with their

frequently

interrupted

dialogue, reflect

the interrupted

thoughts. “Ob sichs

anliess, als wollt

er nicht / lass dich

es nicht erschrecken

etc.” (Although it

appears that He does

not wish to care for

thee / be not

frightened etc.).

The movement is

vocally simple,

though not

homophonic. The 1523

text reminds us that

we should never

doubt the presence

and word of Jesus.

A meditative Recitativo

accompagnato (bass

and strings, No.

7) introduces

the second part of

the Cantata (after

the sermon). Only if

we withdraw

ourselves from the

world, can the word

of Jesus find a

place in out hearts.

Just as He showed

his compassion (as

described in the

Gospel according to

St. Mark) in the

feeding of the four

thousand, so will He

also stand by us in

our need every time

and bless us.

The Aria for

strings and

soprano (No. 8),

“Die Armen will der

Herr umarmen” (The

Lord will embrace

the poor), begins

with a two-part

prelude in which the

‚embracing‘ is

portayed almost

visually by the

alternating lines.

Rising chromatic

passages in the

violins describe how

we will be received

into God‘s mercy.

Then the alto

again explains with

richer language (in

a recitativo

secco, with

arioso

interjections, No.

9), how the faithful

soul, who always

hungers after

Christ, will receive

a crown from Him in

Paradise.

The Duet (No.

10, for soprano,

alto and all the

instruments)

“Lass, Seele, kein

Leiden von Jesu dich

Scheiden” (O my

soul, let no

suffering separate

thee from Jesus) is

like a joyful dance

(gigue?). The text

and music call

cheerfully for trust

in God and constant

faithfulness. In the

B-part, written in a

rather more

complicated way,

more stress is put

on the Mercy, which

awaits the faithful,

if he frees himself

from the bonds of

the body.

This second part

concludes (No.

11) with the

same colourful

Chorale as the first

part, but setting a

different stanza of

the old hymn.

“Tue Rechnung!

Donnerwort”,

BWV 168

(Give an account

of thyself! Word

of thunder), for

the ninth Sunday

after Trinity

The text of this

cantata from 1725,

for the ninth Sunday

after Trinity (which

was the 29th July),

is by Salomon

Franck: taken from

the “Evangelische

Andachts-Opffer”

(Weimar, 1715), in

which just the

closing chorale

dates from 1588

(Bartholomäus

Ringwalt).

The main idea is:

the believer must

account to the Lord

for his actions. He

has only received

his life from God as

a loan, of which he

must make the best

use possible. But

over and above that,

the Lord will show

him mercy, for Jesus

(the Lamb) has taken

his guilt upon

himself.

This two-layered

message is again

apparent in this

Cantata. The first

half (No. 1 to No.

3) deals with the

idea of the

‘outstanding debt‘,

the second (No. 4 to

No. 6) with the

‘debt crossed out‘.

The poet sometimes

used in these lines

almost technical

terms of finance – a

unexpected effect!

The opening text is

packed straight into

a restless and

imperious Aria

for bass and

strings (No. 1).

A single bass voice

is better suited

than a four-part

vocal ensemble to

shout the

commandment “Give an

account of thyself!“

(see St. Luke 2.16 –

the Gospel reading

for this Sunday), as

if it was the Vox

Domini from heaven.

It is regarded by

the poet as a “word

of thunder“, which

“die Felsen selbst

zerspaltet” (splits

the rock itself) and

which our “Blut

erkaltet” (freezes

our blood). The

rapid running

triplet setting

gives urgent power

to the statement

(mostly in the basso

continuo, taken

several times by the

first violin or by

the soloist, and a

few times even

performed in unison

by all instruments).

The frightening

affekt is created by

the dotted rhythm of

the violins and

viola. The Bpart of

the text (“Ach, du

musst Gott

wiedergeben” etc. –

Ah, thou must give

back to God etc.) is

sung by the bass

alone, with the

continuation of the

triplets in the

continuo and, in

turn, the full

material of the

A-part.

There follows a

passionate Recitativo

Accompagnato for

tenor (No. 2),

2 oboes d‘amore and

basso continuo. The

believer recognizes

that God has given

him everything “zum

Verwalten / und

treulich damit

hauszuhalten” (to

administer / and

faithfully to look

after) – and how he

‘callously’ dealt

with it. He now

fears God‘s

punishment (“Wie

kann ich dir,

gerechter Gott,

entfliehen?” – How

can I escape Thee,

righteous God?). Why

do we find the oboes

d‘amore in this

Accompagnato instead

of the usual

strings? Bach‘s

reasons are

sometimes very

simple and natural:

the ‘d‘amore-idea‘

perhaps only points

to God‘s love, from

which He actually

bestows all his

gifts, as the text

emphasises. In

addition Bach

‘displays‘ in this

passage the

mountains, the hills

and the lightning,

of which the three

last lines speak.

The following Aria

(No. 3) also

for tenor has the

same

instrumentation. Is

it too far-fetched

to suppose that the

unexpected,

uncomfortable and

continuous unison of

the two oboes may

illustrate the

“Kapital und

Interessen” (capital

and interest) of the

text? The Aria is a

perfect trio

movement, in which

Bach refrained from

further

word-illustrations.

After this aria the

poet finally takes

the side of the

frightened being:

the Recitativo

secco for the bass

(No. 4)

announces that the

believer‘s debt has

been “quittiert”

(cleared) through

“des Lammes Blut”

(the blood of the

Lamb). There is,

however, a moral

obligation attached

thereto, and he

should also strive

from now on “den

Mammon klüglich

anzuwenden” (to use

the wealth of Mammon

wisely), and he will

“in Himmelshütten

sicher ruhn” (rest

safely in heaven‘s

dwellings).

A short Duet

(No. 5) for

soprano and alto

with basso continuo

(“Herz, zerreiße des

Mammons Kette” –

Heart, break the

chains of Mammon)

follows. That this

text is set as an

imitative duet

clearly indicates

that the faithful

should emulate this

effort. A figure is

repeated 27 times by

the basso continuo

(3x3x3, Eternity?),

which again

expresses very well

the ‘breaking’ of

the chain.

The simply set Closing

chorale (No. 6),

with the 1588 text,

summarizes once

again the whole idea

running through the

Cantata.

Salomon Franck‘s

text for this

Cantata is an

example of how the

Baroque imagery can

sometimes push to

the limit what we

now think of as

‘poetic‘ – and

occasionally even

beyond it, so we

might describe it as

‘shoddy work‘ or

even ‘kitsch‘. De

gustibus et

coloribus non

disputandum est!

(There is no

accounting for taste

and colour!). It is

certain that Bach,

in his great wisdom

did not allow that

to stop him from

setting this text to

music with his best

creative power.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

”Ein

Herz, das seinen

Jesus lebend

weiß”, BWV 134

(A heart, that

knows that his

Jesus lives) for

the third day of

Easter 1724, here

in the later

version of 1731

This piece is also,

like the Easter

Oratorio, a parody

of an earlier

secular Cantata for

a special occasion,

and, in fact, of a

1719 New Year’s

Cantata for Prince

Leopold von

Anhalt-Köthen,

Bach’s employer from

1717 to 1723. Prince

Leopold was a

Calvinist, which

meant that, in the

church services at

his court, there was

no place for

elaborately

conceived Cantatas,

as was usual with

the Lutherans. In

practice, there were

in Köthen only two

annual occasions

when Bach was

required to provide

a (non-religious)

Cantata: at New Year

and for Prince

Leopold’s birthday.

The texts for these

occasional pieces

were written mostly

by Christian

Friedrich Hunold

(1681-1721, his

pseudo nym was

Menantes). They were

so-called Serenatas,

a kind of short

opera libretti,

which were

undoubtedly staged

(if only minimally)

with gestures. At

that time they

called for

professional

singers, who were

able to perform the

sung texts with the

appropriate

conventional

gestures.

The model of our

church cantata (BWV

134a, “Die Zeit,

die Tag und Jahre

macht” (Time,

that makes days and

years) was a

dialogue between two

allegorical persons:

Die Zeit (Time)

(sung by the tenor)

and Die göttliche

Vorsehung (Divine

Providence) (Alto).

In the closing

movement of the

Serenata the soprano

and bass were added,

with no specific

name or rôle but

only for vocal

strength, so that

the piece could end

with a festive

four-part

madrigal-like

movement.

Bach in 1724 – maybe

under some

time-pressure –

composed the parody

for the third day of

Easter, keeping the

original

instrumental forces

of the 1719 Köthen

Serenata. This

religious

remodelling must

have been

particularly

important to him,

since in 1731 he

brought it out again

and even refined it

here and there with

the new text. This

was then published

(in Texte zur

Leipziger

Kirchen-Music, auf

das heilige Osterfest,

und beyden

nachfolgenden

Sonntagen,

anno 1731

(Texts for Leipzig

church music, for

Holy Easter, and for

both the following

Sundays, 1731), in

which this Cantata

is marked “On the

third day of Holy

Easter, in the

church of St.

Nicolai”).

Even in the final

1731 version,

therefore, the work

is still very close

to the secular

original. As in the

Serenata of Hunold

there is no opening

chorus, and it

starts directly with

a Recitativo secco

for two voices

(unusual for church

cantatas). In the

arias and in the

four-part finale

there is still the

original Köthen

music of 1719.

Furthermore there is

no Chorale in this

work, and the new

poet (unknown) does

not use the readings

for the day – he

only refers to the

crucifixion of Jesus

and the meaning of

that for the

faithful.

The piece is scored

for two oboes and

strings. As in the

original Serenata

the alto and tenor

are the main

vocalists, and the

soprano and bass

only join them in

the final movement.

No. 1, Recitativo

for two voices.

The tenor begins

secco: a heart that

believes in the

living Jesus

“empfindet Jesu neue

Güte / und dichtet

nur auf seinen

Heilands Preis”

(feels new goodness

from Jesus / and

speaks only praise

of its Saviour), to

which the Alto adds

(in cheerful figures

dialoguing with the

continuo) “Wie

freuet sich ein

gläubiges Gemüte”

(how a faithful soul

rejoices). So this

beginning is laid

out like a

theatrical event.

The real opening

music of the Cantata

is a festive Aria

for tenor (No. 2),

with all the

instruments –

dance-like music

(reminiscent of a

Passepied, a faster

Menuet), in ABA

form. With “Auf,

Gläubige, singet die

lieblichen Lieder /

Euch scheinet ein

herrlich verneuetes

Licht” (Up,

believers, sing the

lovely hymns / on

thee a glorious

light shineth anew)

the tenor connects

with the words of

the preceding

recitative, where it

commanded “und

dichtet nur auf

seinen Heilands

Preis” (and speak

only praise of its

Saviour). A lively

3/8 motif enters

three times

imitatively in the

two upper voices

(each time one oboe

and one violin part)

and the basso

continuo. After 24

bars of the

introduction the

tenor takes up the

same motif, singing

on his own. The

three successive

entries of the main

motif remains the

principal theme

throughout the

A-part. The B-part

brings new words and

music, initially in

rather a lyrical

mood, but Bach

readopts the main

motif from the

A-part after a while

(even if it is in G

minor instead of the

original B flat

major). The Da Capo

repeats the full

A-section.

There follows a Recitativo

secco for tenor

and alto (No. 3).

In itself, this text

does not require any

dialogue, but Bach

has cleverly divided

it between the two

protagonists, as was

the case in the 1719

Serenata. In Baroque

pictures we are

reminded that Jesus

died on the cross

for the salvation of

man, and descended

to hell, where even

“Satan furchtsam

zittern muss”

(faint-hearted Satan

must tremble). The

alto speaks directly

to Christ: “Mir

Siegeskronen zu

bereiten / Nahmst du

die Dornenkrone dir”

(to prepare for me a

crown of Victory /

Thou took for

thyself the crown of

thorns). The greater

frequency of the

dialogue towards the

end is very

effective, when the

poet declares how

even the grave and

death are no longer

an enemy of the

Christian.

This recitativo

dialogue leads quite

naturally into the

next Duet (No.

4) with

strings and basso

continuo. The alto

and tenor always

sing at the same

time their praise

and thanks with

almost competitive

enthusiasm. In the

B-part of the piece

terms like ‘Sieg’

(victory) and

‘Streit’ (strife)

stand out in the

text. In the

original Serenata

these were also the

main ideas, and the

music was

appropriately

conceived. The first

violins throughout

the piece play

vigorously active

figures, with

positive support

from the others. The

text here is: “Der

Sieger erwecket die

freudigen Lieder /

Der Heiland

erscheinet und

tröstet uns wieder /

Und stärket die

streitende Kirche

durch sich” (The

victor gives rise to

the cheerful hymns /

The Saviour

appeareth and

comforts us again /

And through Himself

strengthens the

struggling Church).

Note the

trumpet-like figure

on “Der Heiland

erscheinet”, sung

impressively twice

by the tenor.

In the following Recitativo

secco (No. 5) for

tenor and alto

the tenor first asks

for continued

support and comfort,

so that near to

death we only “die

for a time”, and

through that we

“enter into Thine

Glory». The alto

then continues with

renewed thanksgiving

and praise, in which

the basso continuo

in the final bars,

after offering only

functional harmonic

support for the

recitativo secco up

till then, suddenly

becomes active in

the moving

statement.

The Cantata then

ends with a

monumental festive Closing

chorus (No. 6)

in ABA form. As in

the original 1719

Serenata, the alto

and tenor, now with

the participation of

all the instruments,

are framed by the

soprano and bass.

The movement is

reminiscent in time

signature (3/8) and

tempo to the tenor

aria (No. 2) – again

a kind of Passepied.

After 32 bars of

concertante

introduction full of

illustrative

ascending motifs the

tenor and alto one

after another begin

with: “Erschallet,

ihr Himmel / Erfreue

dich, Erde” (Ring

out, ye heavens /

Rejoice, O earth).

The

vocalinstrumental

tutti joins in with

“Lobsinge dem

Höchsten / Du

glaubende Schar”

(Sing praises to the

Highest / Thou

faithful throng).

The A-part then

further develops in

organic variety the

motifs and contrasts

which had been

introduced. The

B-part brings in a

new text and

atmosphere. The

tenor and alto

(still the main

people), supported

only by the basso

continuo sing here:

“Erschauet und

schmecket ein jedes

Gemüte / des

lebenden Heilands

unendliche Güte”

(Each soul beholds

and tastes / the

eternal goodness of

the living Saviour),

in which, after four

bars, the first oboe

includes the full

principal motif from

the A-part in a long

solo. The next line,

“Er tröstet und

stellet als Sieger

sich dar” (He

comforts us and

reveals himself as

the victor), is

heard in the four

voices in an

imitative style,

doubled by the

instruments (the

oboe solo spans like

a bridge over this

turning point of the

line when it also

doubles the

soprano). As in the

previous A-part,

this B-part also

develops with ever

new variations of

the existing

elements, until a

homophonic coda with

surprising prosody

suddenly merges into

the Da Capo of the

A-part, so the whole

is rounded off

symmetrically.

Widerstehe doch

der Sünde",

BWV 54

(Stand firm

against sin)

It remains debatable

whether this cantata

from Weimar (1714)

was intended for

Oculi-Sunday (that

is the third Sunday

in Lent), or more

likely the seventh

Sunday after Trinity

(See Dürr, J.S.

Bach, Die Kantaten

p. 292 ff.). The

text is suitable for

both occasions. The

poet G. Chr Lehms

(“Gottfälliges

Kirchen-Opffer”,

Darmstadt 1711)

takes ideas from

both the Epistle

readings. This

Cantata is a

wonderful example of

Bach‘s early work.

From March 1714 Bach

had to provide the

Weimar court with a

Cantata every month,

under his contract

as concertmaster. In

the course of that

he had often used

the rather archaic

five-part writing

for the strings (2

violins, 2 violas

and bass, here, in

my opinion,

Violoncello da

spalla), in which

every part could

well have been

played by a single

string. Thus, in

this cantata as well

and moreover: only

one singer, the

alto, is involved.

This Cantata with

only three movements

is a permanent

reminder that we

should not give way

to sin, because that

leads to death. The

only bright spot is

the remark just

before the end:

“[die Sünde], wenn

man ihren schnöden

Banden mit rechter

Andacht

widerstanden, hat

sie sich gleich

davon gemacht” ([the

sins], if one can

withstand their vile

bonds with true

devotion, one has

caused them to

flee). Thus what

happens is up to us.

Bach immediately

makes us afraid at

the very beginning

of the opening piece

(No. 1). Without

preparation a

dissonant chord is

heard, which has a

penetrating effect

through constant

repetition, is then

briefly resolved

before immediately

returning to the

dissonance – a

symbol of sin, which

holds us – with only

small breaks – in

its power. The

rising motif, which

is first heard in

the second violins

depicts well the

arduous and

painstaking

‘withstanding‘

(rising seventh,

arriving on the

dissonance!). It is

at once imitated in

canon by the first

violin a tone

higher. The alto

begins with the same

image: “Widerstehe

doch der Sünde, /

Sonst ergreifet dich

ihr Gift” (Stand

firm against sin, /

else its poison

overcomes thee). The

two violins and the

alto are the three

active parts which

imitate each other

and intertwine. The

violas and basso

continuo, however,

just repeat the

slowly changing

harmony with

constant emphasis.

On “ergreifet“ there

is a dense weave in

the active parts –

the entanglement and

intertwining in sin.

“Widerstehe“ finally

receives twice a

very long-held note

by the alto – the

withstander, the

‘non-giver-up‘. Bach

is here again a

painter at work,

enigmatic but

masterful! In the

B-part of the aria

(“Lass dich nicht

den Satan blenden

etc” (Do not let

Satan blind thee

etc.) the alto

supplies new melodic

material. Meanwhile,

the basso continuo

takes over the

opening motif

interplaying with

the violins, and

then the A-part is

repeated. This

aria is one of

Bach‘s most

remarquable

creations.

The following Recitativo

secco (No. 2)

is an extended

contemplation by the

poet. He explains

that sin is only

superficially

attractive, but in

reality “ein leerer

Schatten und

übertünchtes Grab”

(an empty shadow and

a whitewashed grave)

and a “scharfes

Schwert, das uns

durch Leib und Seele

fährt” (sharp sword,

which pierces us

through body and

soul). The

“Sodomsäpfel”

(apples of Sodom)

are, according to

old evidence,

fruits, which look

as if they are

edible, but when we

touch them, they go

up in smoke and

ashes, like

deceitful sin. At

the end of

Recitativo the image

of the “scharfes

Schwert das uns

durch Leib und Seele

fährt” is given to

the basso continuo.

Faster, always

rising, figures in

semiquavers (meaning

the attack?) appear

one after another

until they end up in

a decline.

Then the Closing

Aria (No. 3)

is heard, with the

five strings, in

which the two

violins and the two

violas all perform

in unison. The

result is pure

fourpart writing,

with three higher

parts (violins,

violas, vocal

soloist) and the

basso continuo. The

aria is a strict

fugue-like web, in

which the various

motifs alternate and

are combined in

fugal imitation. The

instrumental bass

underneath seems at

first to play a

quasi ‘objective‘

quaver accompaniment

– in which, however,

this gesture is also

certainly thematic,

for on the words

“denn dieser hat sie

aufgebracht” (since

he has brought this

forth) we find

exactly this motif

again. The

descending chromatic

main theme on “Wer

Sünde tut” (Whoever

committeth sin) acts

as the principal

motif, on “Teufel“

(Devil) there is a

long melisma, which

could actually be

regarded as a

snake-like motion

(the snake as a

diabolical symbol!).

In the B-part text

of the aria (“Doch

wenn man ihren

schnöden Banden /

Mit rechter Andacht

widerstanden etc” –

if one can withstand

their vile bonds

with true devotion

etc.), the vocal

part frees itself

from the previously

strictly limited

material, and the

whole structure is

made rather less

severe. The sin,

which “sich gleich

davongemacht” (at

once fled away), is

even illustrated in

striking figures by

the strings and the

basso continuo.

This work, with its

very chamber music

quality, ends here

without a Chorale.

In later cantatas

for solo voice, we

will find several

examples in which,

at the close, three

singers join up with

the soloist, to

round the piece off

with a prayer.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation:

Lindsay

Chalmers-Gerbracht,

Christopher

Cartwright

|

|