|

|

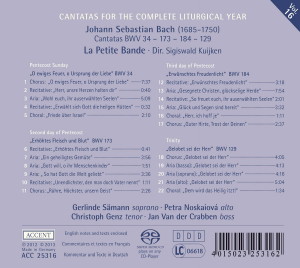

1 CD -

ACC 25316 - (p) 2012

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25316 - (p) 2012 - rectus

|

|

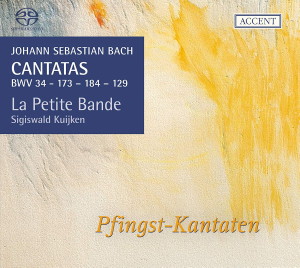

CANTATAS -

Volume 16

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. Pfingstfesttag |

|

|

|

| "O ewiges Feuer,

o Ursprung der Liebe", BWV 34 |

|

16' 08" |

|

| -

Chorus: O ewiges Feuer, o

Ursprung der Liebe |

7'

37"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Herr,

unsre Herzen halten dir |

0' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Wohl euch, ihr

auserwählten Seelen |

5' 09" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Erwählt

sich Gott die heilgen Hütten |

0' 32" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Friede über Israel |

2' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Pfingstfesttag |

|

|

|

| "Erhöhtes

Fleisch und Blut", BWV 173 |

|

13' 41" |

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Erhöhtes

Fleisch und Blut |

0' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Ein geheiligtes

Gemüte |

3' 56" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Gott will, o ihr

Menschenkinder |

1' 51" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, bass):

So hat Gott die Welt geliebt |

3' 36" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano, tenor):

Unendlichster, der man doch Vater

nennt |

1' 11" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Höchster, unsern

Geist |

2' 26" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Pfingstfesttag |

|

|

|

| "Erwünschtes

Freundenlicht", BWV 184 |

|

20' 33" |

|

| -

Recitative (tenor):

Erwünschtes Freudenlicht |

3' 18" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, alto):

Gesegnete Christen, glückselige

Herde |

7' 54" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): So freuet

euch, ihr auserwählten Seelen |

2' 01" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Glück und Segen

sind bereit |

3' 32" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Herr, ich hoff je |

1' 11" |

|

|

| - Chorus: Hirte, Trost der

Deinen |

2' 37" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Gelobet sei der

Herr", BWV 129 |

|

19' 12" |

|

| -

Chorus: Gelobet sei der

Herr |

4' 05" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Gelobet sei der

Herr |

4' 13" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Gelobet sei

der Herr |

4' 16" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Gelobet sei der

Herr |

5' 04" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Dem wird das Heilig

itzt |

1' 34" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Jim Kim, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Sara Kuijken, violin

II

|

|

|

- Ann Cnop, violin

II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Makoto Akatsu, violoncello

da spalla |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Frank Theuns, traverso |

|

|

- Sien Huybrechts,

traverso |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe, oboe d'amore |

|

|

- Dymphna

Vandenabeele, oboe |

|

|

- Jean-François

Madeuf, tromba |

|

|

- Jean-Charles

Denis, tromba |

|

|

- Graham Nicholson,

tromba |

|

|

- Maarten van der

Valk, timpani |

|

|

- Benjamin Alard, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - 1/3 June 2012 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25316 - (1 CD) - durata 73'

23" - (p) 2012 (c) 2013 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

This

CD offers four

cantatas, one for

each of the three

days of Pentecost

(BWV 34, 173 and

184) and one for the

Sunday after

Pentecost, Trinity

Sunday (BWV 29).

Of these four works

only the Trinity

Cantata (BWV 129) is

an original

composition – the

three Pentecost

Cantatas are

‘parodies’, that is

Bach’s own

arrangements of

earlier works. BWV

34 is based on an

earlier Wedding

Cantata (BWV 34a),

BWV 173 on a

previous Birthday

Cantata (BWV 173a)

and BWV 184 on a

previous New Year

Cantata (BWV 184a).

Bach very often

adapted his own

works, and each time

the quality of the

original is

maintained or even

increased (often due

merely to the

quality of the

librettos in the

sacred parody

exceeding the

limitations of

secular occasional

verse).

The original forms

of the Cantatas for

the second and third

days of Pentecost

(BWV 173 and 184)

originated in

Köthen, where Bach

was Kapellmeister to

Prince Leopold of

Anhalt-Köthen. As a

Calvinist this

Prince did not want

any “modern” festive

cantata music in the

services. Only for

the birthday of the

Prince and for the

New Year did the

Prince require a

Festival Cantata

from Bach. These

works were conceived

with more modest

settings,

appropriate for the

court orchestra.

On the settings

of the Cantatas

BWV 173 and 184:

The original Köthen

versions have been

designated today as

BWV 173a and 184a;

Bach was able to

take the score of

BWV 173a and the

separate voices

books of BWV 184a

with him to Leipzig.

In the subsequent

reworkings for the

sacred parody form

(also with new

texts!) he changed

nothing in the

instrumental

settings, just the

vocal setting of

both cantatas being

expanded from two

(only the soprano

and bass, in Köthen)

to four (the

complete vocal

quartet in Leipzig).

The instrumentation

in Köthen is

identical to the

original version of

BWV 184a (the score

of 173a also

tallies, though not

quite so explicitly

in detail): it is

for transverse

flute, 2 violins,

viola, cello and

basso continuo. As a

string bass only

violoncello

was indicated, and

also no ‘doubling’

of the two violin

parts was included,

and since only a

single wind

instrument, the

transverse flute,

was selected (no

oboes, trumpets, or

the like) it can be

concluded that in

these pieces all the

instruments were

used singly, as in

chamber music. With

the Leipzig parody

version nothing – as

mentioned – was

changed. We have in

our recording

completely respected

this limited

instrumentation –

including the use of

the violoncello

(da spalla) as

the only double

bass.

In both the other

cantatas, the string

section is as usual,

with 2 x 2 violins.

As the violoncello

da spalla was

available, it

doubles the normal

double bass (8 ft

violone) in the more

strongly set

sections of BWV 34

and 129.

“O ewiges Feuer,

o Ursprung der

Liebe”, BWV 34

(O Eternal Fire,

O Wellspring of

Love)

This cantata was

composed for a

Pentecost Sunday,

probably in the

1740s, based on the

Wedding Cantata BWV

34a written in 1726,

which had the same

initial text, but

which has not come

down to us complete.

The text author is

unknown. From the

eight parts of the

original version we

find just three

parts used in the

Pentecost version of

only five parts: the

No. 1 remained as

the opening piece,

the original No. 5

in the Wedding

Cantata (after the

ceremony) is No. 3

in the parody and

the No. 4 (then the

conclusion of the

first part) is the

final chorus in the

parody. The piece is

magnificently set:

strings with oboes

as well as three

trumpets, with

timpani.

The Gospel reading

for the Pentecost

Sunday is from St.

John 14 (23-31): an

excerpt from Jesus’s

farewell discourse

to his disciples

(the sending of the

Holy Ghost, and the

benediction for

peace). In the

Epistle reading we

hear from the Acts

of the Apostles what

happened in the

house of Mary: the

sound of wind, how

the fire appeared,

the flaming tongues

which sat upon each

of them, how they

were all filled with

the Holy Ghost and

suddenly spoke every

language.

No. 1 (Chorus)

“O Eternal Fire”:

The text of the

original version had

only to be adapted

slightly for this

new use. From the

flames of love (at

the wedding), the

flames of the Holy

Ghost came

seamlessly upon the

apostles.

As always, Bach also

finds here the

leading

compositional

elements in the

text. Right at the

beginning a

long-held trumpet

note suggests the

“eternal”. (This

long note we find

almost permanently

somewhere in the

score, sometimes in

this, sometimes in

that part). In

between, the “flames

of fire” blaze

up, represented by

the first violins

with incessant, fast

semiquavers. The

oboe and other

instruments help to

give the entire

fabric a very

concertante and

festive image. After

the long

introduction, the

singers finally

enter in a similar

way, with long

sustained notes

alternating in all

parts throughout the

movement, and with

running semiquaver

figures. At the

words “Ursprung

der Liebe”

(Wellspring of Love)

the associated motif

is presented

imitatively in the

order

soprano-alto-tenor,

that is from high to

low - the love comes

like the Holy Ghost

from Heaven. Such

allusions as regards

content are

omnipresent in Bach,

but never dominant –

the music is so much

more than

descriptive. On the

words “Feuer”

and “Liebe”

we find for the most

part active melismas

in the vocal parts,

which then run

parallel with the

first violins. On “entzünde”

(ignite) a very

appropriate

ascending line

appears (what else

would we expect?).

The B section of the

chorus “Lass

himmlische

Flammen/Durchdringen

und wallen”

(Let heavenly flames

/ penetrate and

surge) is more

lyrical for the

voices, while the

violins nevertheless

continue to play

their fast figures

almost constantly,

as a kind of

connecting thread.

The long note on

“Ewigkeit” also

remains present in

the most varied

colours.

The dynamic metrical

foot of the text in

this very energetic

and festive movement

is remarkable: “O

Ewiges Feuer, O

Ursprung der

Liebe” is

written in the

amphibrach foot

(short-long-short),

which with constant

repetition makes a

very binary

impression, very

close to the dactyl.

We find this binary

accentuated in the

music from the

start.

After this masterful

opening movement

there follows a Secco

recitative (No. 2)

for the tenor with

the new text from

the 1740s: God wants

to be with the

people, he will

mercifully enter

their hearts and

thereby sanctify

them.

There follows a

wonderful, almost

sounding like

Christmas, Aria

for alto and

muted strings (No.

3) with two

flutes (probably

played by the

oboists at the

time). The reason

for this ‘Christmas’

feeling is simply

that in the original

version (BWV 34a)

the text reads:

“Happy are you, you

chosen sheep.” The

groom, for whom the

wedding cantata was

written, was

probably a

theologian or

pastor, who also had

“sheep to put out to

pasture” – hence

this pastoral

‘shepherd music’,

which reminds us of

Christmas and which

Bach adopts

unchanged in his new

version. The sheep

here are the souls

whom God has chosen,

through the sending

of the Holy Ghost

(Pentecost!) to

‘live’ thereby, and

to watch over them

as a good shepherd.

The theme of the

‘Good Shepherd’

incidentally appears

again in the Gospel

reading for the

third day of

Pentecost.

Right at the

beginning a long

held note in the

viola part stands

out as a bourdon, a

fifth against the

pulsating bass note.

Who does not

recognize the

bagpipes here (or

rather a lighter

Musette)? The two

transverse flutes

double the violins

an octave higher,

and only in the

B-part of the aria –

“Wer kann ein

größer Heil

erwählen” (Who

can choose a greater

salvation) – are

they once used

independently as a

preliminary

portrayal, which the

violins answer

immediately. The

decision to use the

flutes in this

context is clear. In

the original, they

are played on the

‘shepherd flutes’,

here in the parody

these gentle wind

instruments also

embody the ‘breath’,

the Spirit.

After this

particular aria a

short Secco

recitative (No. 4)

for the bass

returns. This

explains how God

will now pour out

his blessings on the

“heiligen Hütten”

(sacred

dwellings – human

souls), in which

there will come: “Friede

über Israel”

(Peace upon Israel)

(Psalm 128: 6).

With these words the

closing movement

(No. 5)

begins. The Vox

Dei (normally

taken by the bass

soloist) here

solemnly expresses

this benediction for

peace, by the full

vocal quartet, in

two adagio

bars. The careful

listener will hear

how both outer

voices (first

trumpet and

continuo) display a

counter-movement

which opens out:

think of the two

open hands as a sign

of blessing.

The ‘blessing’ leads

directly into the

final music of the

cantata, a kind of

gavotte for every

part (“Dankt den

höchsten

Wunderhänden”

– Thanks for the

lofty hands of

wonder) in alla

breve time. The

figure for “Dankt”

is a rapidly

ascending scale –

the image of

thanksgiving –

upwards, skywards.

In the original text

of the wedding

cantata at this

point was: “Eilt

zu denen heiligen

Stufen” (Hurry

to those sacred

steps). Since Bach

adopted the music

almost unchanged, we

know that the fast

rising figure

originally stemmed

from the word “eilt”.

So one sees how

music can be very

variable in its

naïve

representations. The

orchestra in this

final movement is

almost the central

figure. The vocal

part is entirely

built on the festive

concertante

instrumental

movement and

embedded in it.

This Cantata

exceptionally

contains no chorale,

and does not include

any references to a

church hymn. It is

purely music for a

festival, of which

thanksgiving is the

focus, not

moralizing thoughts,

as we usually

encounter in many

church hymns.

“Erhöhtes Fleisch

und Blut”,

BWV 173

(Exalted Flesh and

Blood), for the

second day of

Pentecost was

probably written in

1724. Our surviving

version, however,

dates from even

later (between 1727

and 1731). In the

latter case a

printed text of the

Cantata was

published, probably

on the occasion of a

repeat performance.

This cantata is also

a reworking of a

Birthday Cantata (“Durchlauchtster

Leopold” – His

most Serene Highness

Leopold – from 1717

or 1722) for Bach’s

former employer,

Prince Leopold in

Köthen.

Bach’s score has

been obtained from

BWV 173a (Köthen),

the separate parts

having been lost.

The piece was

originally for only

soprano and bass

soloists, but for

the Leipzig parody

the alto and tenor

were added. The text

author is also

unknown here. The

music of the

original version has

been retained (with

some adjustments for

the new text). Bach,

however, left out

two arias from the

original composition

(ex-Nos. 6 & 7),

so that the parody

is limited to six

movements. This

cantata also has

neither the

structure of a

chorale nor was one

added later.

The

Gospel for Pentecost

Monday is St. John 3

(16-21): “God so

loved the world that

He gave His

only-begotten Son”.

The Epistle reading

comes from Acts 10

(42-48): It is about

Peter’s speech (“As

Apostles we must

testify that it is

Jesus who was

ordained by God to

be the Judge”), and

the subsequent

outpouring of the

Holy Ghost on all

the attending

audience (even the

Gentiles among

them!). In the text

some hints of these

readings are to be

found.

The Cantata begins

with an Accompagnato

recitativo (No. 1)

for tenor with

strings. In the

original version

this recitative was

set for soprano: a

solemn short

prologue in honour

of Leopold. Here,

however, man is so

to speak addressed

solemnly, and

congratulated that

he is now sanctified

in flesh and blood,

erhöht

(exalted) by God’s

Spirit and

Fatherhood. The

brilliant upward

rising vocalise on “erhöhtes”

could not be left

out ...

There follows an Aria

(No. 2) for the

tenor (in the

first version

likewise for

soprano) with two

transverse flutes,

strings and basso

continuo. The upper

instrumental line is

played by the violin

and two flutes in

unison. This creates

a special sound,

sweet and

affectionate. In

both versions the

text deals with the

heavenly gifts, of

which Leopold (or in

our cantata: mankind

in general) is now

part. Festive but

still intimate,

flower-filled sounds

urge us to celebrate

and give thanks, in

order to “Gottes

Treue

auszubreiten” (spread

God’s faithfulness).

No. 3 is not

called an Aria,

but is rather a

short vivace

for alto

with string

accompaniment.

Because God wants

mankind to do great

things, the text

declares “Mund

und Herze, Ohr und

Blicke bei diesem

Glücke und so

heil’ger Freude

nicht ruhen”

(mouth and heart,

ears and eyes should

not rest with this

happiness and such

holy joy). As in the

original version in

which the bass sang

this fragment with

an almost identical

text, this piece

contains here an

additional

invitation to

thanksgiving and

praise. It is about

God’s intentions

toward mankind, but

the music is rather

strict and metered

(Bach writes staccato

for both violin

parts).

A Duetto (No. 4)

for soprano and

bass now

follows, with

strings and flutes -

a gentle,

minuet-like music

delights the

listener. While the

two soloists in the

original version

almost as

allegorical figures

congratulated and

sang to the Prince

Leopold, here

instead of Leopold

God himself is

praised for his

goodness (“God so

loved the world”,

see the Gospel

reading!). This duet

is very peculiar in

its structure. Each

of the three

(six-line) ‘verses’

of the duet is set

in a different key,

and each is a fifth

higher (G Major – D

Major – A Major).

The first verse (G

Major) is sung by

the bass alone, and

accompanied by the

strings alone. The

second verse (D

Major) is taken by

the soprano, the two

flutes join in, and

the violins in unison

with the viola play

the bass part as a

so-called Bassetto,

an octave higher

than the violoncello

and organ would have

done. Only the last

verse (A Major) is

sung by both the

soloists, the two

flutes in unison

play the minuet

upper voice over the

strings with basso

continuo, and the

first violin

suddenly takes off

on its own with

rapid ornaments (diminutions

of the old-fashioned

kind). The reason

for this may well be

that Bach, with

these fast

concertante notes,

wishes to indicate

the “offenbartes

Licht”

(revealed Light),

which is mentioned

in the text. However

that may be, it

results in a

beautiful

intensification in

the course of this

third part.

There follows a Recitativo

for 2 (Duetto)

(No. 5) for

soprano and tenor

and basso continuo

(originally for

soprano and bass,

because there was

then only soprano

and bass). The text

hardly had to be

adapted for the new

version, only in the

first verse, which

is in the original:

“Durchlauchtigster,

den Anhalt Vater nennt”

(Most serene one,

whom Anhalt calls

Father). In our

parody this is: “Unendlicher,

den man doch Vater

nennt”

(Eternal one, whom

one calls Father).

(You will notice

that the rhythm of

the prosody remains

unchanged!). The

rest of the

Recitativo verses

could remain

unchanged. This

Recitativo is

atypical, because it

is more a measured arioso

than a free

recitativo. This is

especially true from

the sixth bar on

when the recitativo

disappears and a

beautiful web of

three voices

(soprano, tenor,

basso continuo)

emerges. The tenor

follows the soprano

in clear imitation,

below which the

basso continuo

proceeds with

regular quavers

until shortly before

the end of the

singing it comes

into its own and

finally brings the

instrumental

postlude to a close

with a high soaring

figure (see the

text: “soll sich

der Seufzer Glut

zum Himmel

schwingen” –

the fervour of our

sighs ascends to to

heaven). In this

Recitativo a few

bars earlier the

continuo part is

already even higher

(because of the

textual content!),

so that it could

certainly be

concluded that the

five-string

violoncello (da

spalla) was

intended. The

sister-Cantata BWV

184 confirms this

instrumentation.

The Cantata ends

with a Chorus

(No. 6) for

the full vocal

quartet and all

instruments (in the

original version,

where only two

singers

participated, this

movement was also

called ‘Chorus’.

Here it can clearly

be seen that the

word ‘Chorus’ did

not at all

correspond at the

time to the present

meaning.)

In this piece we

encounter the gentle

tutti sound of the

individual strings

with both flutes.

The music for this

text points

‘inwards’ (“Rühre,

Höchster, unser

Geist” – Stir,

O Lord, our spirit)

is courtly, elegant,

in turn minuet-like

and delightful. Left

over from the

original version are

the sections where

the soprano and bass

dialogue without the

alto and tenor, to

which in the new

version Bach simply

added ‘all voices’

in the tutti-sections,

without much

individuality

(rather like the

inner voices in the

French orchestral

style, which yes is

not far away in this

final part).

“Erwünschtes

Freudenlicht”,

BWV 184

(Light of joy

desired)

Newly arranged for

the third day of

Pentecost, 30th of

May 30, 1724, in

Leipzig, this

Cantata is a parody

of a lost cantata

from Köthen. It is

so to speak a

sister- Cantata of

BWV 173, which has

been discussed

above, and which, in

1724, was given the

day before in

Leipzig. Like BWV

173, it was also

performed again in

1731, as the date on

the printed text

indicates.

The setting is very

similar. The

original version was

probably (like BWV

173) only sung by

the soprano and

bass. The separate

voices of the new

sacred version are

kept. Here you can

see that Bach simply

reused the Köthener

instrumental parts

(only the organ part

was rewritten, as it

had to be transposed

down a tone), and

the partbooks of the

(now four) singers

were rewritten with

the new text. We do

not know who carried

out the

rearrangement of the

text.

The Cantata begins

with a Recitativo

accompagnato (No.

1) for tenor

with two flutes and

basso continuo. The

flute parts of the

original version fit

the new text of the

sacred version

exactly, as if in

the original text

the words had also

been of “light” or

“flames”. One might

assume that the

(secular) Köthener

version was a New

Year’s Cantata, in

which case the

“light of joy”

simply hinted at the

New Year festival,

at the candles and

torches, or at the

light of the New

Year. In any case,

the short,

continuously

repeated flute

motifs are to be

interpreted as an

auditory record of

flickering candle

flames – childlike

and simple as Bach

is so happy to do.

The Gospel reading

of the day (St. John

10, 1-11) above all

relates that Jesus

is the “Good

Shepherd”, and it

immediately follows

that a movement with

shepherd flutes can

be expected. One can

quote further

associations with

flutes, as we shall

discuss later.

The text of the

Rezitativo is a long

monologue, in which

the believer is

called on to thank

and honour God, who

concludes a new

covenant with

mankind through

Jesus, for which the

solemn symbol of the

poet is a “Light of

Joy desired”. Man

should follow that

light to the grave.

This accompagnato

is very close to the

style of a measured

arioso, and

before the end (with

“Drum folgen wir

mit Freuden bis

ins Grab” -

That is why we

follow with joy to

the grave) Bach

actually writes ‘arioso’.

From then on, the

tenor does not sing

recitative but

melody with

melismas. The flutes

are silent and the

basso continuo

continues with quiet

striding quavers. In

the last verse

(which is set again

in a more recitative

style), the flutes

return with their

‘flame’ images.

Now comes an Aria

(duet) (No. 2) for

soprano and

alto, with all

the instruments in a

flowing 3/8 time

(similar to the

French Passepied

dance) in a free

rondo form. “Gesegnete

Christen,

glückselige Herde”

(Blessed Christians,

blissfully happy

flock). The flutes

double the first

violin in the tutti

sections. In the

interludes, they are

more independent and

bring rapid scale

motifs (the joy of

the shepherds, but

perhaps also the

flicker of the Holy

Ghost at Pentecost). These

motifs are later

taken over by the

first violin. The

text again

paraphrases what has

been said in the

preceding long

monologue, this time

in a shorter form.

What is new though

is the idea of the

B-part “Verachtet

das Locken der

schmeichlenden

Erde” (Despise

the enticements of

flattering earth).

The vocal parts are

almost throughout

kept homophonic

(that is in the same

rhythm, in intervals

of a third and a

sixth). This creates

again a rather

traditional and

simple Christmas

feel. In the B

section of the aria

(“Verachtet das

Locken”) the

scene changes. The

pair of flutes

dialogue with the

two singers, but

then for a short

time they are

replaced by the

first violin and the

singers alone for

the words “dass

euer Vergnügen

vollkommen kann

sein” (that

your pleasure could

be perfect). Then a

short version of the

instrumental

introduction to the

A-part is heard as a

ritornello, and the

singers repeat the

B-text. Where

previously on “schmeichelnden

Erde” there

was a long vocalise,

here there is an

even longer vocalise

on “Locken”,

in an elaborate

dialogue with the

instruments. The

entire A-section is

then repeated. No.

3 is a Secco

Recitativo for

tenor. The

text continues to

develop the idea of

the shepherd and the

happy flock, but

also points to the

redemption of the “Sündenbanden”

(bonds of sin) by

the “Held aus

Juda” (hero

from Judah) (Jesus’s

journey to hell to

free the sinners)

and the “Kraft

von Gottes Arm

über die Feinde” (the

power of God’s arm

over the enemy). It

finishes with a

double image: “Hier

schmecket die

Herde die edle

Weide, und dort

hoffet sie

volkommne

Himmelsfreude” (Here

the flock tastes the

noble pasture, and

hopes for perfect

heavenly joy there).

At the word “Himmelsfreude”

the Secco Recitativo

suddenly becomes a

delightful dialogue

between the tenor

and basso continuo

(violoncello and

organ) - an image of

shared happiness?

This is followed by

an Aria (No. 4)

for tenor with solo

violin and basso

continuo. The

dialogue continues,

this time between

the tenor and the

solo violin,

supported by a

flowing quaver bass,

in 3/4 time. A

similarity to a

polonaise can be

noted from the

musical setting. The

text of the aria is

connected to the

previous recitative:

“Glück und Segen

sind bereit / Die

geweihte Schar zu

krönen”

(Happiness and

blessedness are

ready / to crown the

sacred throng). On “krönen”

there is always a

little decorative

motif which reminds

us (at least on

paper) of a crown.

The whole aria is a

moment of serene

contemplation. It is

played with no

action, nothing

dynamic.

Then follows a Choral

(No. 5), a new

movement, which was

set as a Secco

Recitativo in the

original BWV 184a.

It is the eighth

verse of “O

Herre Gott, dein göttlich

Wort” (O Lord

God, thine divine

word) by Anarg von

Wildenfels (1526).

The content of this

verse takes up again

the idea of the

shepherds. May God

always stand by and

lead to salvation

those who believe in

him.

One might have

expected that this

Choral would close

the Cantata, but

there follows a

solemn Chorus

(No. 6), which

resembles an elegant

and charming

gavotte. This

movement was the

closing movement of

the secular

original. The

original

incidentally was

used again by Bach

in later years

(1733) as the finale

of his so-called

“Hercules” Cantata “Lasst

uns sorgen, lasst

uns wachen”

(Let us tend, let us

watch) (BWV 213).

Here also, as in the

sister Cantata BWV

173, it is clear

that initially the

soprano and bass

were the only

singers. Bach only

adding the alto and

tenor in the A-part

as simple inner

voices. The B

section remains a

duet for soprano and

bass. The flutes

double the first

Violin with

additional

embellishments

(simple diminutions

with faster note

values). The basic

idea of the Choral

and the whole work

is in other words

repeated: May God

forever remain the

Good Shepherd.

“Gelobet sei der

Herr, mein Gott”,

BWV 129

(Blessed be the

Lord, my God), for

the Trinity

Sunday, 1726 (or

1727).

The Trinity Sunday

Feast can be said in

the Christian faith

to form the epilogue

to the entire arc,

which in the first

half of the church

year spans from

Advent through

Christmas – Epiphany

– Good Friday –

Easter – the

Ascension to

Pentecost, when God

as the ‘Crown of His

work’ sends us the

Holy Ghost. The

Trinity is now

complete: God as

Father, Son and Holy

Ghost. It is

celebrated on this

Sunday immediately

after Pentecost as a

‘whole’, a unity.

After this end point

when the Trinity is

completed, the

services in the

second half of the

church year are used

for all kinds of

reflections on and

from the Holy

Scriptures, always

within the main

sweep of the first

half. The Sundays of

the second half are

simply named

according to their

order: first,

second, third (etc.)

Sunday after

Trinity. There are

usually 26 Sundays,

and only

exceptionally 27

(when Easter falls

early in the

calendar year),

until the year

begins again with

Advent.

Bach’s position as

Kantor of the St.

Thomas School in

Leipzig began on the

first Sunday after

Trinity in 1723.

Cantata BWV 129 is a

chorale cantata.

Bach, on the first

Sunday after Trinity

in 1724, as he began

his second annual

cycle of Cantata

compositions,

decided to compose a

full year of

cantatas in which an

existing chorale

text with all its

verses would be

taken as the basis,

either completely

verbatim or

partially

paraphrased. The

first and last

verses always

retained the

original wording.

(Sometimes choral

sermons were also

given, that is

sermons, which are

based on only a

single chorale

text). This plan,

however, only lasted

until Easter 1725.

In later years, Bach

tried, with similar

chorale cantatas, to

fill the gap that

had remained open

from Easter to

Pentecost 1725, so

that finally a

complete annual

cycle of cantatas of

this type would

exist.

Cantata BWV 129 is

one of these later

‘fillers’. The

chorale text by

Johann Olearius

(1665) here is

retained verbatim

for all five verses.

The first stanza

sings of God the

Father, the second

of the Son, the

third of the Holy

Ghost. The last two

verses then praise

the one God existing

in three persons.

The piece is richly

set with an

orchestra of 3

trumpets with

timpani, transverse

flute, 2 oboes and

strings with basso

continuo.

The No. 1,

marked Chorus,

begins with a long

concert-like

instrumental

introduction, in

which the flute and

the two violins play

virtually throughout

in unison with an

almost unbroken

stream of semidein

quavers, and this is

very often

strengthened by the

first oboe, yet in a

simplified way.

Around this stream

two groups hang

about initially

playing

antiphonally: basso

continuo, second

oboe and viola on

the one hand, and

the three trumpets

with the timpani on

the other. In the

nineteenth bar the

soprano enters with

the chorale melody

in regular long

notes, all alone

without the support

of any instrumental

doubling, and sings

the text in clearly

separate blocks. The

other three singers

come in with lively

dynamic

interjections. In

the middle of the

very active and

colourful web of the

surrounding

instruments and

singers, the chorale

melody has not much

chance of being

clearly heard. This

is also due to the

soprano part being

pitched rather low.

It must, therefore,

be assumed that Bach

did not want this

chorale melody to be

placed absolutely in

the centre. Its

presence was in

itself apparently

enough (we can think

of the many hidden

beauties in the

architecture of so

many old churches,

which, because of

the darkness or too

great a distance

from the eye, are

very often hardly

accessible!). To

conclude this very

striking and

impressive movement

(in honour of the

Father!) the

instrumental

introduction is

heard again.

Movement No. 2

(an Aria for

bass with

basso continuo)

stands in stark

contrast to this.

Simply because of

the pure two-part

notation, instead of

orchestral richness,

the composition

emphasises here the

direct and personal

relationship with

the Son (“der

sich für mich

gegeben hat” –

‘who hath given

himself for me’,

according to the

text). This aria

could be understood

as an intimate

dialogue between the

faithful and the

Son.

The third verse of

the hymn of 1665 is

again an Aria,

this time for

soprano (No. 3)

with obbligato

flute, obbligato

violin and continuo.

Here is the praise

of the Holy Spirit:

“des Vaters

werter Geist, den

mir der

Sohn gegeben”

(worthy Spirit of

the heavenly Father,

which the Son gave

to me). The

instruments (first

bass) repeat,

alternating with the

simple main voice

from the beginning,

a short motif which

runs rapidly up and

down.

It seems to me that

this symbolizes the

Spirit, the

‘breath’, the spirit

which from now on

blows where it will.

The soprano never

adopts this

particular image in

her vocal

ornamentation (as on

“gelobet” –

praised, or on “schafft”

– creates), but

maintains an

instrumental role.

The No. 4 is

again a ‘chamber

music’ Aria for

alto with

obbligato oboe

d’amore and basso

continuo. Here, as

already mentioned,

the Trinity is sung

as a whole, after

the Holy Ghost had

approached as the

last to come and

completed the

Trinity. This piece,

therefore, is (as

expected) a pure

three-part fabric in

itself, in which all

the voices are

equally important.

That Bach selected

the oboe d’amore as

an obbligato

instrument could

well be because it

is associated with

the idea of ‘love’,

which is at the

heart of the

Trinity, the deep

bond.

A long, purely

instrumental

introduction (only

two parts) opens the

aria. Are these not

God the Father and

God the Son, joined

later by the Holy

Ghost (the alto

soloist)? This

assumption can

certainly be made.

The aria is written

in a flowing 6/8

time, and has a very

lyrical character.

Note the sudden

unison of the three

parts on the words “Gott

Vater, Gott der

Sohn und Gott der

Heilge Geist”

(God the Father, God

the Son and God the

Holy Ghost): the

unity of the

Trinity.

The last verse of

the hymn (No. 5)

Chorale will

again be played by

the entire ensemble,

thus forming a

tonally symmetrical

counterweight to the

opening movement.

The Chorale is sung

in different blocks

line by line in

simple homophonic

four parts. This

time the flute

doubles the soprano

melody in the upper

octave. The movement

is concertante

throughout for the

instruments, the

trumpet playing the

major role in the

festive interludes.

The text here is

once again the

universal summation

proclaiming: “Gelobet

sei mein Gott

/ In alle

Ewigkeit.”

(Blessed be my God,

For all eternity).

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright

|

|