|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25315 - (p) 2011

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25315 - (p) 2011 - rectus

|

|

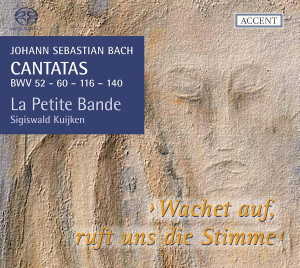

CANTATAS -

Volume 15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

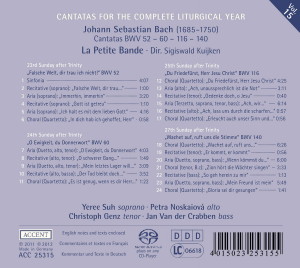

| 23. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Falsche Welt,

dir trau ich nicht!", BWV 52 |

|

14' 51" |

|

| -

Sinfonia |

4'

07"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Falsche

Welt, dir trau ich nicht! |

1' 00" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Immerhin,

immerhin |

3' 20" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Gott

ist getreu |

1' 10" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Ich halt es

mit dem lieben Gott |

4' 16" |

|

|

| -

Choral: In dich hab ich

gehoffet, Herr |

0' 58" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 24 Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "O Ewigkeit, du

Donnerwort", BWV 60 |

|

14' 15" |

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (alto, tenor): O

Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort |

4' 03" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto, tenor): O

schwerer Gang zum letzten Kampf |

1' 49" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (alto, tenor):

Mein letztes Lager will mich

schrecken |

3' 09" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto, bass): Der

Tod bleibt doch der menschlichen

Natur... |

3' 52" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Es ist genug |

1' 22" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 25. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Du Friedefürst,

Herr Jesu Christ", BWV 116 |

|

17' 23" |

|

| -

Choral: Du Friedefürst, Herr

Jesu Christ |

4' 25" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Ach,

unaussprechlich ist die Not |

3' 11" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Gedenke

doch, o Jesu |

1' 40" |

|

|

| -

Trio (soprano, tenor, bass):

Ach, wir bekennen unsre Schuld |

6' 14" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ach, lass

uns durch die scharfen Ruten |

0' 57" |

|

|

| - Choral: Erleucht auch

unser Sinn und Herz |

0' 56" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 27. Sonntag nach

Trinitatis |

|

|

|

| "Wachet auf,

ruft uns die Stimme", BWV 140 |

|

25' 38" |

|

| -

Choral: Wachet auf, ruft

uns die Stimme |

6' 26" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Er kommt,

er kommt |

0' 56" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, bass):

Wenn kömmst du, mein Heil? |

6' 00" |

|

|

| -

Choral (tenor): Zion hört die

Wächter singen |

3' 33" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): So geh

herein zu mir |

1' 13" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, bass):

Mein Freund ist mein |

5' 49" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Gloria sei dir

gsungen |

1' 41" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yeree Suh, soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Jim Kim, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

II

|

|

|

- Ann Cnop, violin

II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minenn, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe, oboe d'amore |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe, oboe d'amore |

|

|

- Emiliano Rodolfi,

oboe, taille

|

|

|

- Rainer Johannsen,

bassoon |

|

|

- Olivier Picon, horn |

|

|

- Alessandro

Denebian, horn |

|

|

- Benjamin Alard, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Beguinenhofkerk,

Sint Truiden (Belgium) - 5-6

December 2011 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25315 - (1 CD) - durata 71'

16" - (p) 2011 (c) 2012 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

These

are four Cantatas

which Bach wrote for

the last four

Sundays before

Advent:

BWV 52 “Falsche

Welt, dir traue

ich nicht!”

[False world, I

trust thee not!] -

23rd Sunday after

Trinity.

BWV 60 “O

Ewigkeit, du

Donnerwort” [O

Eternity, thou

thunderous word] - 24th

Sunday after

Trinity.

BWV 116 “Du

Friedefürst, Herr

Jesu Christ”

[Thou Prince of

Peace, Lord Jesus

Christ] - 25th

Sunday after

Trinity.

BWV 140 “Wachet

auf, ruft uns die

Stimme”

[Awaken ye, the

watchman calls us] -

27th Sunday after

Trinity.

There are 27,

usually 26, Sundays

between “Trinity”

(Trinity Sunday, the

Sunday after

Pentecost) and the

beginning of Advent.

Only exceptionally,

when Easter falls

between the 22nd and

the 26th March, is

there a 27th Sunday.

During J. S. Bach’s

Leipzig years, this

was the case only

twice: 1731 and

1742. The Cantata

BWV 140, for this

27th Sunday was in

fact first performed

in Leipzig in 1731

and probably in 1742

as well.

We have performed

this extra Cantata

in preference to BWV

70 (“Wachet! betet!

betet! Wachet!”)

(“Watch! Pray! Pray!

Watch!”), which Bach

wrote in 1723 for

the 26th Sunday. We

will catch up with

BWV 70 later, so

that our series,

which is intended to

contain a Cantata

for each Sunday of

the ecclesiastical

year, will not lack

this Sunday.

The texts of the

last Cantatas before

Advent recorded

here, are primarily

based, as might be

expected, on the

Gospel readings for

these Sundays, all

of which are taken

from the Gospel

according to St.

Matthew. In these

fragments a sterner,

warning tone can be

heard. As soon as

Advent begins (the

start of the

ecclesiastical

year!), the texts

adopt a much more

positive tone,

because now the

Saviour is expected,

who will turn away

all evil from us, if

we put our trust in

Him.

“Falsche Welt,

dir traue ich

nicht!”, BWV52

(for

the 23rd Sunday

after Trinity), was

first performed on

the 21st November

1726.

This is the last of

the three cantatas,

which Bach wrote for

the 23rd Sunday

(1715 in Weimar,

then in Leipzig in

1724 and 1726). The

reading from St.

Matthew (Ch. 22,

15-22) for this

Sunday contains the

passage in which the

Pharisees ask Jesus

a clever trick

question, whether it

was lawful to give

tribute to Caesar,

to which Jesus

replies, “Render

therefore unto

Caesar the things

which are Caesar’s”–

an answer that was

perfect and

indisputable.

The ever anonymous

poet of this 1726

Cantata is outraged

by the cunning and

hypocrisy of the

Pharisees. He urges

the Christians, in

contrast, to lead a

righteous life and

to renounce the

falsehood (“sich der

Falschheit ab zu

kehren”); that is

his main theme.

How often in cantata

poetry the first

half (in this case,

the recitativo secco

No. 2 and the Aria

No. 3) treats the

theme from rather a

negative viewpoint,

while in the second

half positive

statements prevail.

(Already in the

B-part of the Aria

No. 3 the affekt

becomespositive).

In this cantata Bach

gives the entire

poem to the soprano.

(Only the final

Chorale by Adam

Reusner, 1533, is

sung by a vocal

quartet). The

decision to use the

soprano voice for

everything is

perhaps explained by

the fact that here

the poet speaks

throughout in the

first person - as

someone who is

anxious and dejected

and looks for

support.

Traditionally those

emotions are more

connected with a

woman. The soprano,

even though with

Bach it was mostly

sung by a boy, is

thus in this case

the most suitable

interpreter of the

role, just as, in

other cases, the

Voice of God is

always entrusted to

the bass. One could

also take it that

the poet here allows

‘the soul’, or the

‘bride’ (in the

mystical sense), to

express her feelings

of dejection; in

this case anyway a

soprano was usual.

The poem starts

immediately with a

long monologue

recitative that

could never be set

as an aria or a

chorus. So Bach

places here, as the

opening movement, a

festive instrumental

Sinfonia (No. 1),

with oboes,

bassoons, horns and

strings. This is an

earlier version of

the first movement

of the Brandenburg

Concerto no 1. Why,

in 1726, Bach did

not reuse the

already existing

1721 ‘Brandenburg

version’ but

reverted to an even

earlier version is

not documented.

(Note in passing

that in this earlier

version of the piece

no part for violino

piccolo or for the

violoncello is to be

found). Bach first

made this fine

modification of the

treble and bass

parts in his

revision of the

complete Concertos

for the Margrave of

Brandenburg.

Why exactly this

piece as an

‘Overture’? A

possible clue could

be that in this

concerto movement,

right at the

beginning, the two

horns contribute a

rather strange

sequence to the

developing music of

the other

instruments, which

Bach could have

easily left out,

without altering the

character of the

piece. In fact it

sounds like a

totally unexpected

hunting call in

triplets without any

organic relation to

the context –

completely remote

and sounding like a

strange collage! Did

Bach want to draw a

picture of falsehood

with a false

element? Who knows?

Perhaps I am trying

unnecessarily to

discover a definite

reason. In his later

Cantatas Bach very

often used a

Sinfonia as an

introduction, taken

from earlier pieces.

Probably he did not

focus very

consciously on the

related cantata

texts. In the first

place these

Sinfonias possibly

served to give the

service a greater

solemnity,

especially when

there was no

suitable vocal

movement capable of

taking over this

function.

After this Sinfonia

the sung part of the

Cantata begins. The

soprano starts with

a long and

passionate Recitativo

secco (No. 2),

in which the poet

presents his

pessimistic

feelings. Everything

in this world is

hypocrisy and

falsehood, “O

jämmerlicher Stand!”

(O wretched state!)

(at the same time he

shows his

familiarity with the

Old Testament, in

which he refers us

to an example of

this falsehood: Joab

kills Abner in

Samuel II. Ch. 3, v

27).

There follows an Aria

(No. 3), with

string

accompaniment:

”Immerhin, immerhin

/ Wenn ich gleich

verstoßen bin”

(However, however, /

If I am immediately

rejected). The poet

now sums up: this

false world is my

enemy, God is my

friend. Bach bases

the theme and rhythm

of this aria on the

poet’s words. The

regular, imitative

opening motif of the

violins (an

ascending broken

scale) clearly shows

the alienation, the

rejection. On the

other hand, after

the string

introduction, the

soprano calls out to

us the word

“Immerhin”, as

directly as

possible. The

rhythmic shape of

the ‘Immerhin’ then

becomes the second

building block of

the whole aria.

Everything is

exclusively in the

minor. The only

section of text, in

which the major key

is briefly used, is

“O, so bleibt doch

Gott mein Freund /

der es redlich mit

mir meint” (Oh, if

God still remains my

friend / it really

means everything to

me). The word

‘Freund’ is later

illustrated by Bach

with an appropriate

vocalise, in

combination with the

two previously

mentioned building

blocks of the piece.

So at this point

everything comes

together.

After this aria any

pessimism fades

away, and in the

following Recitativo

(No. 4) ...

”Gott ist getreu /

er will, er kann

mich nicht

verlassen” (God is

true / He will, He

can not forsake me)

the “Gott ist

getreu” is heard

right at the

beginning as a kind

of ‘arioso’. It is

repeated once more

in the middle of the

recitative, and

appears at the end

three more times in

dialogue with the

basso continuo.

The following Aria

(No. 5) (“Ich

halt es mit dem

lieben Gott / Die

Welt mag nur alleine

bleiben” – I am

beside my dear God /

The world, however,

may just be left)

celebrates the

rediscovered trust

in God in a

delightful way. The

soprano is framed by

three oboes and the

basso continuo, in a

continuous ensemble.

The three oboes play

together the whole

time in the same

three-part rhythm.

It is natural to see

in this the Trinitas

of the Christian

God. That no other

instruments were

involved (apart from

the basso continuo)

illustrates quite

clearly the intimate

connection of the

soul (soprano) with

her beloved God. In

the Aria No. 3,

which is about the

‘false world’, the

strings were active.

Yet here the ‘false

world’ is abandoned

and the strings are

replaced by oboes.

Wind instruments

were often

associated with the

spiritual, here

‘spirit’ also means

breathing!

What is remarkable

about this aria is

that Bach sets the

solemn text like a

noble dance. The

soprano sings for

the most part

syllabically, so

that the text can be

understood very

clearly, and only

the words “(ich)

halt (es)” und

“(lieben) Gott” are

given a long

sustained note. This

is no coincidence.

In the B-part of the

aria, with the lines

“Also kann ich

selber Spott / mit

den falschen Zungen

treiben” (Thus can I

myself ridicule the

false tongues), the

soprano moves

completely away from

the framework with

some faster figures,

while the Trinitas

oboes steadfastly

continue on their

own way.

With this the poet

ends his Cantata

poem. As a closing

Chorale (No. 6)

Bach uses the first

verse of “In dich

hab ich gehoffet,

Herr” (In Thee is my

hope, Lord) (1533,

Adam Reusner) in a

simple four-part

setting. The vocal

quartet is

reinforced by all

the instruments

which took part in

the Sinfonia.

“O Ewigkeit, du

Donnerwort”, BWV

60

(for the 24th

Sunday after

Trinity, the 27th

November, 1723)

Bach composed two

cantatas for this

opening text – BWV

60 is

chronologically the

first of the two,

and the second, (BWV

20), followed seven

months later, on the

11th June 1724, the

First Sunday after

Trinity. It has

already appeared in

Volume 7 of our

series (ACC 25307).

The Cantata title is

the opening text of

the hymn “O

Ewigkeit, O

Donnerwort” (O

Eternity, O

Thunderous word) by

Johann Rist from

1642. Where Cantata

BWV 20 presents all

twelve verses of the

poem (it is a

so-called Chorale

Cantata), in BWV 60,

recorded here, only

the first verse is

used, and in a very

unusual way, as we

shall see.

The Gospel for this

24th Sunday after

Trinity deals with

the episode of the

‘raising from the

dead of the daughter

of Jairus’ in St.

Matthew (Ch. 9,

8-26).

The librettist,

unknown as ever,

does not go into the

miracles of Jesus,

but takes the

opportunity to

reflect on his own

death and

resurrection. He

chooses the dialogue

for his dramatic

form. First ‘fear’

and ‘hope’ stand one

against the other,

and later the voice

of God himself

speaks of fear.

The action of the

Cantata was set by

Bach for alto

(Fear), tenor (Hope)

and bass (Vox Dei)

with the

participation of one

horn, two oboes

d’amore, strings and

basso continuo. The

soprano only appears

in the four-part

closing Chorale.

The first movement

is headed “Aria”

(No. 1). The

piece, however, also

contains, next to

the actual solo

voice, the chorale

of the title as a

cantus firmus. It is

a strange duet –

neither a normal

aria nor a normal

chorale.

At the beginning we

hear 13 bars of

instrumental

introduction, in

which, above a

long-held bass pedal

note (Eternity!),

the upper strings

express the thunder

with repeated (at

first deep) notes.

Against that the

oboes make rather

melodic

interjections with

breaks in between,

sometimes imitative,

then again in

parallel thirds or

sixths. It could be

thought that, with

these horizontal

interjections, Bach

was sketching the

moving cloud cover.

(Such associations

must not be made,

yet personally, and

to my increasing

astonishment, I see

how Bach gets

information from the

texts, which he

often quite

schematically, or

even naïvely,

translates into

compositional

elements). After the

long pedal note the

instrumental bass

takes up the

repeated ‘thunder

notes’ of the

violins and viola.

In bar 13 the bass

becomes calm again,

and the strings play

piano. Then, in bar

14, the cantus

firmus enters with

the first line of

text (sung by the

alto – Fear – with

the horn doubling).

The number 14 is one

of the clearest

“Bach-numbers” (that

is B + A + C + H, in

figures 2 + 1 + 3 +

8). Who knows

whether there is not

also a conscious

allusion here, as if

Bach wanted to

indicate how much he

associated himself

with these opening

words. Under this

cantus firmus

opening the

instruments continue

with the elements

already described,

changing

continuously. After

an interlude of six

bars the second line

of the Chorale

follows, and, after

an even shorter

interlude, the third

line. Only then the

tenor (Hope) begins

his aria with the

words “Herr, ich

warte auf dein Heil”

(”Lord, I wait for

Thy Salvation”: a

quotation from

Genesis Ch. 49.18 -

also Psalm 119, v.

166). These are his

only words. During

the eight remaining

lines of this very

pessimistic Chorale

verse, this same

contrasting and

hopeful message from

Genesis is heard

continuously. On the

“warte” the tenor

almost always sings

long sustained notes

or longer vocalises,

which illustrates

the duration of the

waiting. The whole

instrumental

introduction is

later repeated as an

epilogue.

There follows a Recitativo

(No. 2) for

alto and tenor. Fear

(alto) again loses

itself even further

in dark thoughts

about the pains of

death and “der

Sünden große Schuld”

(of the great guilty

sins). On the other

hand Hope (tenor)

speaks another

language from its

point of view: I

offer up my life to

God, “Er gibt ein

Ende den

Versuchungsplagen”

(He puts an end to

the torments of

temptation). As

always, Bach shows

himself here a

master of

recitative.

Particularly vivid

in the second

intervention of Fear

is the Andante on

“martert diese

Glieder” (tortures

these limbs). The

response of the long

tenor vocalise with

continuo on

“ertragen” (endure)

is the perfect

counterbalance.

The Aria (No. 3)

is a duet,

accompanied by a

solo oboe d‘amore

and a solo violin.

Fear and Hope (alto

and tenor) talk to

each other, without

any real dialogue in

the sense of a

fruitful exchange of

ideas. The listener

will determine for

himself which words

correspond best to

his feelings. The

two solo instruments

clearly show the

different layers of

thought. The oboe

theme is obviously

connected with Fear,

and the violin, with

its ascending and

descending scales,

certainly

illustrates the

opening text of

Hope: “Mich wird des

Heilands Hand

bedecken” (The hand

of the Saviour will

protect me). The

predominantly dotted

rhythm of the

continuo plainly

belongs to the world

of Fear: “Mein

letztes Lager will

mich schrecken” (My

deathbed wants to

terrify me). When

finally Fear asserts

“Das offne Grab

sieht greulich aus”

(The open grave

looks hideous) and

Hope continues with

“es wird mir doch

ein Friedenshaus”

(It is for me a

house of peace) Bach

shows us das Grab in

the obbligato

instruments up to

six times, with

three clear notes.

Between two equal

notes at the same

pitch there is

another played

short, a fourth

lower – the image of

a pit between two

borders? At least

that is how it

occurred

spontaneously to me.

In Recitativo

(No. 4), Fear

is no longer

confronted by Hope,

but their dark

thoughts about death

and hell are

interrupted by the

Voice of God himself

(the bass). After

the first part of

the recitative sung

by Fear (“Der Tod

bleibt doch der

menschlichen Natur

verhasst, und reißet

fast die Hoffnung

ganz zu Boden” -

Death still remains

odious to human

nature, and drags

almost all hope to

the ground), the

Voice of God, out of

nowhere, suddenly

pronounces, in a

peaceful, singing

manner (‘arioso’ is

required by Bach), a

sentence from the

Apocalypse (14:13)

“Selig sind die

Toten” (Blessed are

the dead). This

theatrical divine

interjection is

repeated after each

of the ensuing

thoughts from the

still depressed

Fear. In each of

these three

interventions this

is the whole

Apocalypse

quotation, until the

third time it is

finally completed:

“Selig sind die

Toten / die in dem

Herrn sterben / von

nun an” (Blessed are

the dead / who die

in the Lord / from

now on). This last

(complete) arioso

section ends with a

wonderful vocalise

on „sterben“, which

is followed by a

simple ”von nun an”.

This third divine

intervention finally

convinces the rigid

Fear: ”Wohlan! soll

ich von nun an selig

sein / so stelle

dich, O Hoffnung,

wieder ein / Mein

Leib mag ohne Furcht

im Schlafe ruhn /

der Geist kann einen

Blick in jene Freude

tun.”“(Well then!

from now on will I

be blessed / so take

thy place again, O

Hope / My body may

rest asleep without

fear / the spirit

can catch a glimpse

of that joy).

Thus, ultimately,

the “Donnerwort” has

overcome the fear.

Without another aria

the closing

Chorale (No. 5)

follows, which Bach

takes from another

hymn: “Es ist genug”

(It is enough) by

Joachim Burmeister

(1662). The original

beginning (“Es ist

genug” : a, b c# d )

Bach ‚distorts‘

melodically in an

unexpected way to

‘a, b c# d#’! The

resulting,

incredibly strange

tritone motif just

intensifies the

bitterness of the

text “es ist genug”.

When, with the third

line of the text

(“Mein Jesus kömmt”

– My Jesus comes)

the same distorted

phrase recurs, it

gets another

harmonisation and

achieves, it seems

to me, a quite

different effect.

Jesus will end the

misery of this world

with his power, He

will crush the evil.

On the third from

last line of the

Chorale, “mein

großer Jammer bleibt

danieden” “(My great

misery remains

behind me) Bach,

with a chromatic

descending bass

line, then gives us

one of his boldest

harmonic phrases,

(the misery behind

me?). Here the

extreme limit of

correct four-part

harmony is achieved

(or even exceeded?).

“Du Friedefürst,

Herr Jesu Christ”,

BWV 116

This Chorale Cantata

was written for the

26th November 1724

(the 25th Sunday

after Trinity in

this year). It is

based on a

seven-verse hymn by

Jacob Ebert (1601).

The anonymous text

editor used verses 1

and 7 of the old

hymn verbatim, and

reworked the second,

third and fourth

verses (they are

Nos. 2, 3 and 4 of

the Cantata). The

fifth and sixth

verses he reworked

as well, combining

them in a single

paraphrase (No. 5 of

the Cantata).

The Gospel reading

for this Sunday is

St. Matthew 24,

15-28 – certainly

not a pleasant text.

It is very

worthwhile to read

it again before

listening to this

Cantata. Matthew

talks about the

abomination of

desolation (as

announced by the

prophet Daniel),

which mankind will

meet prior to the

Day of the Last

Judgment. A disaster

will then occur

greater than any

mankind has yet

known, warns Daniel.

The Cantata text

writer, however, has

hardly incorporated

allusions from the

St. Matthew reading.

He follows, as I

said, the hymn, in

which, above all,

forgiveness, and

especially help in

distress, is prayed

for, during all

these terrible

events that we can

encounter in our

lives – especially

for protection in

times of war (No.

5).

The work is scored

for two oboes

(because of the

chosen key of A

major these are

oboes d‘amore here),

strings, four-part

vocal ensemble and

basso continuo. A

‘corno’ (horn) is

brought in for the

1st and 6th

movements, to

strengthen the

Chorale melody in

the soprano.

The Cantata begins

with a full-scale

tutti movement

(No. 1) with a

pronounced

concertante

character. In the

instrumental

introduction, before

the entry in bar 16

of the four singers

with the first line

of the Chorale,

there is a very

active dialogue

between the basso

continuo and the

other parts. The eye

is especially caught

by the the numerous

rising motifs and

bridge passages,

alternately in the

upper parts and the

continuo. I believe

these are inspired

by the last line of

this verse: our cry

to Jesus’ Father, –

(a prayer to heaven,

thus upward). The

continuous very

agile concertante

figures of the first

violins illustrate

well the oppressive

difficulties which

afflict mankind.

This is in strong

contrast to the

melodious and

homophonic choral

singing of the two

first lines, “Du

Friedefürst, Herr

Jesu Christ / Wahr’

Mensch und wahrer

Gott” (Thou Prince

of Peace, Lord Jesus

Christ / Truly man

and truly God). The

instruments continue

their concertante

playing, and, after

a long interlude,

the tenor, the bass

and the alto climb

up one after the

other to the words

of the third line,

“Ein starker

Nothelfer du bist”

(A powerful helper

art Thou), with the

same motif that we

heard at the

beginning of the

movement from the

oboes and strings.

The fugatolike

successive entries

of this text

illustrate well

God‘s everlasting

help. The fourth

line is also taken

by the three lower

voices with the same

instrumental motif,

in which there is a

long, active

vocalise on “leben”

but a long, held

note on “Tod”. This

is another example

of how Bach

carefully derives

the elements of his

composition from the

words of the poem.

So it is the same in

the next two short

lines: “Drum wir

allein / im Namen

dein” (So we alone /

in Thy Name), where

he sets the words

‘Drum’ and ‘wir

allein’ literally

alone, sung

homophonically by

the three lower

voices. The final

line of the verse is

then, like the first

two, simply and

clearly presented by

the four singers all

together. This

monumental movement

is rounded off with

a repeat of the

whole introduction.

This is followed by

an Aria (No. 2)

for alto, with

obbligato oboe

d‘amore and continuo

in the Baroque

reworking of the

second original

verse of the

Chorale. “Ach,

unaussprechlich ist

die Not” (Ah,

unspeakable is the

distress), sings the

poet. The cry ‘Ach’

in the introduction

is taken by the oboe

as the initial

motif. Its three

ascending notes,

rapidly following

each other, (f#, g#,

a), reproduces

perfectly what the

voice does with an

impassioned cry on

this ‘Ach’. After

the highest note of

‘Ach’ the melodic

line falls. From

this low point, it

soars by the degrees

of a diminished

seventh chord, again

upwards, in order

then to sink once

more in a pure triad

sequence. So this

theme reflects the

great and passionate

variety of the first

line of the poem. In

this movement the

oboe and voice

repeat themselves in

widely different

variations, but the

instrumental bass

does not do this at

all, rather it

repeats its own

melodic line, which

often expresses the

upward surge, the

distress of the

soul. On ‘Not’ Bach

from time to time

writes a long

sustained note, in

the middle of the

continuously running

web; even ‘Angst’

gets a long,

chromatically

rising, line with a

tremolo. This

plaintive note is

then imitated by the

oboe d‘amore, which,

throughout the

piece, appears to

strengthen and share

the emotions of the

singer. The basso

continuo

relinquishes its

rather lyrical rôle

only twice, in order

to portray briefly,

with a staccato

arpeggio figure, the

‘Dräuen’ (the rage,

the threat) of the

‘erzürnten Richters’

(angered judge). The

alto clearly

illustrates both

words in a long

vocalise.

A short Recitativo

(No. 3) for

tenor contains the

paraphrase of the

original third verse

of the Chorale. As

with several

recitatives in other

cantatas, Bach

writes here, as a

brief introduction

in the basso

continuo, the

beginning of the

chorale melody (“Du

Friedefürst, Herr

Jesu Christ”),

clearly recognisable

as a signal. After

this the tenor sings

his first line

(“Gedenke doch, o

Jesu, dass du noch

ein Fürst des

Friedens heißest” –

Remember Thou, O

Jesus, that Thou art

also called a Prince

of Peace) in a

recitativo secco as

usual, supported by

simple harmony. This

process is then

repeated, with the

bass playing the

Chorale opening

again in a new key,

before the tenor

concludes with the

question “will sich

dein Herz auf einmal

von uns wenden?”

(will Thine heart

suddenly turn away

from us?).

The following,

touching Terzetto

(No. 4) for

soprano, tenor and

bass, with basso

continuo, is the

paraphrase of the

fourth original

verse “Ach, wir

bekennen unsre

Schuld” (Ah, we

admit our guilt).

The ‘Geduld’

(patience) and the

‘unermesslich

Lieben’ (love beyond

measure), about

which the guilty man

is asking here, are

perceived throughout

the entire

composition as an

enigmatic idea. In

this long and

uniformly extended

piece an incredibly

patient and almost

immeasurable

peacefulness

predominates. None

of the three singers

even raises the

voice individually,

everything flows

along horizontally

and with restraint.

The singers sing

continually as a

unit of three – one

could almost believe

that Bach wished to

compare the divine

Trinity with a human

reflection.

As an introduction

the basso continuo

sets out the coming

mood. The rhythmic

figure of four notes

(syllables) is

repeated six times,

which we will

hear onstantly

in the vocal prosody

during the whole

Terzetto, for

example, in “und

bitten nichts “ (and

ask for nothing) or

also with “als um

Geduld” (save Thy

patience). The basic

structure of the

piece is AB-A. An

interlude (a

transposition of the

introduction)

separates the A-part

from the B part.

Here then the new

text, “Es brach ja

dein erbarmend Herz”

(It broke even Thy

merciful heart), is

brought together

(instead of one

after the other) by

the three singers in

rather a painful

harmonic twist over

an exceptionally

homophonic pedal

note. In the process

‘Herz’ gets a long

sustained note in

the two highest

voices. With “als

der Gefallnen

Schmerz” (when the

pain of the fallen)

the passage becomes

a long chromatic

moment, and

‘Schmerz’ now gets a

similar long

sustained note (this

time in the two

lower voices),

resulting in a

painful affekt. When

Bach repeats this

B-text once more

about twenty bars

later, it is indeed

done in the same

way, but on

‘Gefallnen’ there

follows this time a

more complex

vocalise – a

descending

semiquaver figure

(the ‘Fallen’!) in

all three voices.

This leads into a

long, extended

‘Schmerz’, now in

all three voices. A

replay of the

complete

introduction leads

us to the much

expanded da capo of

the A-part. Then the

full introduction is

heard for the third

time as an epilogue.

I would like to

describe this unique

movement as a

‘spiritual

madrigal’; there are

not many comparable

pieces in Bach‘s

works.

The alto, who was

not used in the

Terzetto, follows

now Recitativo

accompagnato (No.

5) with the

reworked fifth and

sixth verses of the

old Chorale. The

poet beseeches God

for mercy and

understanding during

the difficult

trials. Expressly

“Friede” (peace) is

sought “für ein

erschreckt geplagtes

Land” (for a

frightened and

troubled land).

The cantata

concludes with

simple four-part Chorale

(No. 6) with

the seventh original

and last verse of

the hymn of J. Ebert

from 1601: “Erleucht

auch unser Sinn und

Herz” (Enlighten

also our soul and

heart).

“Wachet auf, ruft

uns die Stimme”,

BWV 140

for the 27th

Sunday after

Trinity (25th

November 1731)

As mentioned, not

every year has 27

Sundays between

Pentecost and

Advent. Bach only

experienced this

twice during his

Leipzig period

(1723-1750). So one

may reasonably

assume that he was

particularly pleased

to have to compose a

cantata for this

Sunday, which does

not occur every

year. He probably

also repeated the

work on the next

occasion (only

eleven years

later!).

The readings for the

27th Sunday follow

those of the

previous Sundays.

The First Epistle of

Paul the Apostle to

the Thessalonians

urges them to be

ready for the Day of

the Last Judgment,

and St. Matthew Ch.

25 (1-13) relates

the parable of the

ten virgins, who

were invited to his

wedding by the

bridegroom. Five of

them were so foolish

as to bring no oil

for their lamps in

case it would be

needed at night. The

five others,

however, had been

wise enough to think

of it. Then, when

the bridegroom does

not arrive until the

night, the first

five ask their

friends to share

their oil with them,

but they refuse and

hurry away to the

feast. The foolish

young women only now

go in search of oil

and so arrive too

late for the

wedding. There the

bridegroom denies

them entry: “I know

you not, who are

you?” This story is

intended to show how

man should always be

prepared to meet

Jesus (the

bridegroom), that is

to be ready for the

moment of the Last

Judgment. Thus the

parable fits

perfectly into the

series of warnings

about the end of

time that, time and

again, we find for

the last few Sundays

before Advent.

The picture of the

bridegroom in the

parable from St.

Matthew was already

present in the Song

of Songs, that part

of the Old Testament

not recognised by

some branches of

Christianity. At the

same time this

picture also

describes the bridge

to Advent, when

Jesus (the groom)

will arrive.

In addition, this

Cantata is a Chorale

Cantata, like BWV

116 discussed above.

Bach had not quite

finished his

year-long cycle of

Chorale Cantatas in

1725 (started on 1st

Sunday after

Trinity, 1724, with

BWV 20 „O Ewigkeit,

du Donnerwort“), and

he attempted to

complete it in later

years. The Cantata

BWV 140 of 1731 is

one of the later

Chorale Cantatas.

The original, on

which the anonymous

author leant, is

initially similar to

a hymn by Ph.

Nicolai (1599). This

has only three

verses. The text

editor, also

anonymous, decided

to retain all three

of them verbatim

(movements 1, 4 and

7), and then to add

four new fragments

of text (nos. 2, 3,

5 and 6), in which

he sings, in his own

way, of the mystical

union of the

bridegroom with his

bride. Unlike most

of the Chorale

Cantatas, there is

here no ‘reworking’

of older verses, but

the poet has fitted

in an appropriate

complementary

structure.

The work is laid out

on a large scale,

with a festive

instrumentation:

besides the vocal

quartet it includes

a horn, three oboes

(two “normal” and a

Taille, that is an

Alto-Oboe), a

bassoon and strings

with basso continuo.

The violin group is

provided with an

important part for

Violino piccolo,

which increases the

richness of sound

from the whole.

Movement No. 1

(Chorale)

contains the 12

verses of the first

Chorale strophe of

1599. It is

presented by the

singers in clearly

separated sections.

As in many other

cases, in this piece

the soprano sings

the Chorale melody

with long notes,

doubled by the horn.

(Incidentally it

should be noted here

that such a

doubling, in the

case of a setting of

the vocal parts for

choir, would really

be unnecessary. So,

is not such

doubling, which

occurs very often,

an additional

argument in favour

of the one to a part

performance?) At the

beginning of the

piece, with short

staccato notes, the

basso continuo

emphasizes, strongly

and continuously,

the pace of the 3/4

time. Played

alternately by the

strings and winds,

the upper

instruments repeat a

dotted rhythm, which

is just as striking.

Four bars later the

rôles are reversed.

The bass takes over

the dotted rhythm,

and the second

violins and viola

(alternating with

the 2nd and 3rd

oboes) play the

staccato beats. At

the same time an

ascending motif, at

first syncopated,

awakens (“Wachet

auf!”) in the 1st

violin and piccolo

violin, which play

the entire ‘opening

chorus’ in unison,

in a lively dialogue

with the dotted

rhythm. After one

bar the first oboe

imitates the upper

violins. The

contrasting

successive entries

of this faster motif

will be a main

connecting thread

for the instrumental

setting throughout

the piece. From time

to time longer

semiquaver passage

work develops from

this in the upper

violins, sometimes

discreetly joined by

the first oboe, and

supported by the

continuo in regular

quavers. During the

whole course of the

piece the entire

‘orchestra’ only

uses alternately the

building blocks

mentioned above.

After 16 bars the

choral cantus firmus

starts in the

soprano and horn

parts. Below this

the alto, tenor and

bass develop a

motif, which is

clearly derived from

the beginning of the

Chorale. After a few

bars of instrumental

interlude the second

line of the Chorale

text is heard: “Der

Wächter sehr hoch

auf der Zinne” (The

watchman is very

high on the

ramparts). Bach

cannot resist

playing a simple

game with this text.

The lines of the

three lower singers

rise up with these

words and hold a

long note on high.

In addition the

first oboe and the

upper violins

present a similar

line, while in the

second violins and

the second oboe the

same line is even

played briefly

(almost for fun!)

upside down (the

watchman comes down

again???). Bach,

like an imaginative

painter, uses every

such available

opportunity – and

that only makes his

music richer. The

third line of the

Chorale verse (“Wach

auf, du Stadt

Jerusalem”) (Awaken

ye, thou city of

Jerusalem), like the

second, after the

entry of some

instrumental bars,

has the cry of ‘Wach

auf’ set

homophonically, and

repeatedly, so that

it can not be

ignored.

The 12 lines of the

verse should be read

in four groups each

of three lines. In

order to make this

division clear, Bach

makes the interludes

after each three

lines considerably

longer than usual.

After the first

three lines, the

music (including the

introduction) starts

all over again from

the beginning, but

now to the words of

the fourth, fifth

and sixth lines,

exactly as is the

case in the old

Chorale. After a new

interlude (12 bars

instead of 16) the

next group of three

lines (7, 8, 9)

begins. On this

occasion line 9

stands out, which

contains only the

word “Allelujah”.

Here the alto, tenor

and bass, for the

only time, develop a

faster motif, which

(although somewhat

hidden) contains the

syncopated

‘awakening’ quaver

figure of the upper

violins from the

fifth bar. In the

last three lines

(10, 11, 12) it

should be noticed

how Bach, at the

beginning of the

last line, (“Ihr

müsset ihm entgegen gehen”

– You must go to

meet Him), allows

the “Ihr” to be

called out twice on

its own, and

homophonically,

before he goes on

with the movement.

Thereby, He meets

us, the listeners,

with greater

certainty: You, yes,

that is us!

After the last line,

the whole

introduction is

repeated as an

epilogue.

This great movement

could almost be

described as a

novel. Yet, in the

end, this is only a

triviality, because

the power and beauty

of the composition

is fantastic, even

without this

description. Bach

goes far beyond the

finest analysis.

In the simple Recitativo

secco (No. 2)

for tenor the

Baroque text editor

announces the

arrival of the

bridegroom, and the

“Töchter Zions”

(daughters of Zion)

– in the broadest

sense, all of us –

are invited to the

wedding feast (as

mentioned, on the

threshold of

Advent!).

In the following Aria

Duetto (No. 3)

the poet presents

the soul (soprano)

and the bridegroom

(bass). In the

A-part of the text

the soul asks “Wenn

kömmst du, mein

Heil?” When comest

thou, my salvation?

To which the groom

replies, “ich komme,

dein Teil” (I come,

as part of thee) and

the soul replies,

“Ich warte mit

brennendem Öle” (I

wait with burning

oil, an allusion to

the reading from St.

Matthew). In the

B-section they both

almost take the

words from each

other‘s mouth (the

soul: “Eröffne den

Saal zum himmlischen

Mahle” (Open the

hall to the heavenly

banquet); the groom:

“Ich eröffne den

Saal zum himmlischen

Mahle” (I open the

hall to the heavenly

banquet), then

again, the soul,

“Komm, Jesu” (Come,

Jesus), and the

groom at the end:

“Komm, liebliche

Seele” (Come, sweet

soul)). In this duet

of great beauty we

are witnessing the

preparation for the

mystical union. It

almost seems to us

that we hear the

Song of Songs.

Bach added to this

duet with basso

continuo a lyrical

and virtuoso part

for Violino piccolo,

which, throughout

the whole piece,

joins both lovers

together like a

tendril with varied

ornamental lines. As

an introduction, the

little violin

straight away plays

the opening lines of

the soul and the

bridegroom one after

the other, and then

develops its

embellishments,

which will continue

to accompany the

dialogue. The

thought occurred to

me while playing

that Bach had chosen

the Violino piccolo

instead of the

normal violin in

order to fly around

almost like a little

cupid in this

duetto. (Perhaps I

exaggerate here, but

less and less can I

escape the

impression that

Johann Sebastian

never shied away

from such Baroque,

theatrical

associations, not

even in his church

works. Unlike today,

there was at that

time no absolute

separation between

the secular and the

spiritual. This can,

for example, be seen

from the fact that

Bach reshaped many

of his ‘secular’

cantatas, often with

really minimal

changes to the

music, for his

‘spiritual’

cantatas.)

The opening motif of

the Duetto is very

reminiscent of the

famous alto aria

with solo violin in

the St. Matthew

Passion “Erbarme

dich”, in which this

aria theme also

leans clearly on the

beginning of the 4th

Sonata (in C minor)

for violin and

obbligato

harpsichord. The two

characters have a

musical dialogue

with each other in

an affekt of

elegance and

intimacy. Some

striking rhetorical

beauties should

particularly be

mentioned: the

repeated long

‘extensions’ on “Ich

warte” in the

soprano; then, at

the beginning of the

B-section, on

“(er)öffne” in both

voices, which now

turns the opening

motif upside down,

clearly suggesting

the invitation to

‘leave open’. Also

in this piece the

entire introduction

of the piccolo

violin with basso

continuo is repeated

as an epilogue.

There follows (No.

4), the second

original verse of

the Chorale

by Nicolai (1599),

“Zion hört die

Wächter singen”

(Zion hears the

watchmen singing),

set for unison

strings (both

violins and the

viola), tenor and

basso continuo.

After the

introduction for the

strings, the tenor

sings – the one well

separated from the

other – the twelve

lines of this stanza

from the Chorale,

sparingly decorated.

From the beginning

the combined violins

and viola form a

delightful,

narrative

counterpart (the

piccolo violin is

silent, because the

part is too low for

this smaller sister

pitched a minor

third higher). This

movement, because of

the inspired and

simple character of

the motifs in the

string section, has

become very famous -

once heard, it long

remains in the ear.

Perhaps Bach, in his

own way, wanted here

to relate to a

traditional folk

song – for instance

the song of the

watchmen, who heard

the daughters of

Zion? This

conjecture appears

plausible to me. The

composer himself

later used this pure

three-part movement

(in which each voice

is absolutely

independent of the

other two) as the

first piece in his

six “Schübler

Chorales” for organ

(BWV 645).

The No. 5 is

a Recitativo

accompagnato

for bass (the

bridegroom) and

strings. The author

continues the scene

of the mystical

union. The bride is

now invited into his

chambers by the

bridegroom, where

she will forget the

fear and the pain

endured.

In the subsequent Duett

(No. 6) the

soul seals the union

with the bridegroom

(“Mein Freund ist

mein, und ich bin

sein” – My friend is

mine, and I am his)

with obbligato oboe

and basso continuo.

Now a little Cupid

flies around no

longer (the Violino

piccolo), but the

Holy Spirit himself

is there (Spiritus –

breath, so a wind

instrument, the

oboe). The piece

displays a noble

excitement, a great

internal joy. At the

beginning of the

A-section, strangely

enough, the

distribution of the

text between the two

characters is

somewhat arbitrary,

because logically,

the soul would have

to sing both of

first two lines

(“Mein Freund ist

mein, und ich bin

sein”) instead of

the second line

being left to the

bridegroom – unless

the bridegroom would

sing “und ich bin

dein” (and I am

thine). In the

original text of the

Song of Songs, from

which the poet

quotes here, it is

clearly “sein” – not

“dein”. Here perhaps

we encounter a

dilemma that Bach,

just this once and

against the text so

to speak, has

resolved in favour

of the music,

contrary to the

spirit of the words

anyway, and

immediately allows

the dialogue to

begin. One could,

however, also argue

that in this deep

union the difference

between ‘mein’ and

‘dein’ has really

disappeared, so that

the bridegroom can

simply continue or

undertake the

sentence of the

soul. The listener

will form his own

opinion about this.

The fact is that in

the B-part the

simple logic

re-enters (here the

poet speaks again,

without being

hindered by any

verbatim quotation

in the text!) - both

characters speak

clearly in their own

names (soul: “Ich

will mit dir” etc. –

bridegroom: “Du

sollst mit mir”

etc).

In this duet,

two-part

instrumental

passages (the

introduction, the

interludes, the

epilogue) alternate

seamlessly with

four-part writing

(this is when the

soul and the

bridegroom are also

involved).

Everything flows as

if by itself, always

inventively fresh.

Let us note how Bach

dwells longer on

“Himmels Rosen”

(heaven‘s roses),

and “Wonne” (bliss)

at the end of the

B-section. It is as

if he would like us,

the listeners, to

share in the

heavenly joys for

longer.

This wonderful

Cantata for the rare

27th Sunday ends (No.

7) with the

original third verse

of the old Chorale

by Philipp Nicolai.

It is set by Bach in

simple four-part

writing. The chorale

melody is doubled

very colourfully by

the horn and Violino

piccolo (in the

upper octave). Why

this piece is

notated in the old

fashioned way in

minims, instead of

the familiar

crotchets, is not

known. Perhaps Bach

intentionally wanted

to retain the

archaic aspect, in

order to increase

the ‘eternal value’

of the old words,

which describe for

us the glory of the

heavenly Jerusalem,

and, at the end of

the hymn, clearly

point to Advent and

even to Christmas:

“Des sind wir froh /

Io, io! / Ewig in

dulci jubilo” (For

this we are happy /

Io, io! / Eternally

in dulci jubilo).

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright

|

|