|

|

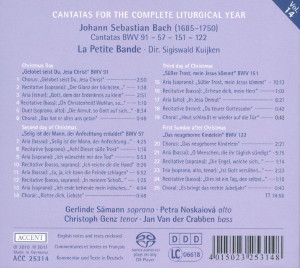

1 CD -

ACC 25314 - (p) 2010

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25314 - (p) 2010 - rectus

|

|

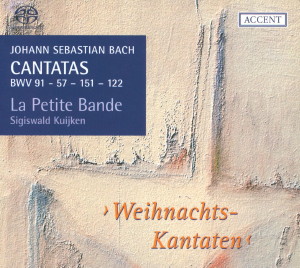

CANTATAS -

Volume 14

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. Weihnachtstag |

|

|

|

"Gelobet seist

Du, Jesu Christ", BWV 91

|

|

17' 51" |

|

| -

Chorus: Gelobet seist Du,

Jesu Christ |

2'

50"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Der

Glanz der höchsten Herrlichkeit |

1' 38" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Gott, dem der

Erdenkreis zu klein |

2' 51" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Oh

Christenheit! |

1' 10" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, alto):

Die Armut, so Gott auf sich nimmt |

8' 34" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Das hat er alles uns

getan |

0' 48" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Weihnachtstag |

|

|

|

| "Selig ist der

Mann, der Anfechtung erduldet",

BWV 57 |

|

24' 09" |

|

| -

Aria (bass): Selig ist der

Mann |

4' 25" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Ach!

Dieser süße Trost |

1' 16" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Ich wünschte

mir den Tod |

5' 53" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass, soprano):

Ich reiche dir die Hand |

0' 26" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Ja, ja, ich kann

die Feinde schlagen |

5' 52" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass, soprano):

In meinem Schß liegt Ruh und Leben |

1' 25" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Ich ende

behende mein irdisches Leben |

4' 04" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Richte dich, Liebste,

nach meinem Gefallen |

0' 48" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Weihnachtstag (St.

Stephanus) |

|

|

|

| "Süßer Trost,

mein Jesus kömmt", BWV 151 |

|

18' 59" |

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Süßer Trost,

mein Jesus kömmt |

10' 13" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Erfreue

dich, mein Herz |

1' 02" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): In Jesu Demut |

6' 21" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Du teurer

Gottessohn |

0' 42" |

|

|

| - Choral: Heut schleußt er

wieder auf die Tür |

0'

42" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. Sonntag nach

Weihnachten |

|

|

|

| "Das neugeborne

Kindelein", BWV 122 |

|

13' 06" |

|

| -

Chorus: Das neugeborne

Kindelein |

2' 21" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): O Menschen, die

ihr täglich sündigt |

5' 15" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Die

Engel, welche sich zuvor |

1' 14" |

|

|

| -

Trio (soprano, alto, tenor):

Ist Gott versöhnt und unser Freund |

2' 23" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Dies ist

ein Tag, den selbst der Herr gemacht |

1' 10" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Es bringt das rechte

Jubeljahr |

0' 43" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Jim Kim, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Makoto Akatsu, violin

II, violoncello da

spalla

|

|

|

- Katharina Wulf, violin

II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Frank Theuns, transverse

flute, recorder

|

|

|

- Dimos de Beun, recorder |

|

|

- Katharina Andres,

recorder, oboe

|

|

|

- Rodrigo

Gutiérrez, oboe |

|

|

- Jean-François

Madeuf, horn |

|

|

- Lionel Renoux, horn |

|

|

- Koen Plaetinck, timpani |

|

|

- Benjamin Alard, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Augustinus

Kerk, AMUZ, Antwerp (Belgium) -

19/21 December 2010 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25314 - (1 CD) - durata 74'

56" - (p) 2010 (c) 2011 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

These

four Christmas

cantatas were

written in Leipzig.

BWV 91 (Christmas

Day) and BWV 122

(the Sunday after

Christmas) are from

1724, while the

other two, BWV 57

(for the Second Day

of Christmas, the

Feast of St.

Stephen) and BWV 151

(for the Third Day

of Christmas) were

written in 1725.

Both the works from

1724 are so-called

Chorale Cantatas.

There are two types

of this genre: the

first simply takes

over an existing

hymn completely as

the text without

further arrangement.

In the second the

poet uses an entire

existing hymn text

as a basis, where he

retains certain

verses of the

original (at least

the first and last

verses), and reworks

other verses with

new words, so that a

text emerges, which

gives rise to a new

musical setting

(with arias and

recitatives). Our

Cantatas BWV 91 and

BWV 122 from 1724

belong to this

second type.

“Gelobet seist

Du, Jesu Christ”,

BWV 91

(“Blessed art

Thou, Jesus

Christ”)

This chorale cantata

for Christmas Day of

1724 uses as a basis

the seven-verse hymn

by Martin Luther

(from 1529), with

the same opening

text. The anonymous

poet took over the

first and last

verses of Luther’s

hymn word for word

as the beginning and

end of the whole. He

also used the second

verse verbatim, but

he mixed it with new

lines of his own

(Recitativo No. 2);

the other verses are

transformed into

arias (Nos. 3 and 5)

and a recitativo

accompagnato (No.

4).

The Luther hymn, “Gelobet

seist Du, Jesu

Christ”

(Blessed art Thou,

Jesus Christ) was an

integral part of the

Christmas Day

service; we may

presume that the

text and melody were

very well known to

the faithful, so

that they could

follow the course of

the composition

better than we can,

who today, for the

most part, no longer

feel this

familiarity.

The first stanza (No.

1, Chorus)

tells how the host

of angels rejoice at

the birth of Jesus

to the virgin

(Mary). Naturally,

festive, colourful

music is suitable

here. In addition to

the voices and

strings, Bach brings

in two high horns in

G with timpani,

besides the frequent

use of the oboe

trio.

At the beginning of

the 12-bar

instrumental

introduction a

‘pedal note’ on G is

heard (i.e. for 12

bars, the same G

note is held or

repeated, without

other notes

interfering). Bach

combines this, in an

imitative way, with

a rapid ascending

scale motif (in

semiquavers) and a

descending arpeggio

motif (in quavers),

and the horns hold a

long G major chord.

Thus, gradually, a

joyful jumble

develops, but

transparently

conceived. Then the

horns themselves

take over the rapid

semiquavers, with a

more ‘circular’

motif. These various

motif elements are

found, by the end of

the movement, in a

richer and more

inventive variety in

all the parts. The

hymn text is

presented in five

separate blocks,

line by line (four

lines and a final

Kyrie eleison). The

soprano sings the

wellknown chorale

melody in long equal

notes (without

instrumental

doubling; the melody

hides itself, so to

speak, rather

discreetly in the

general jubilation),

while the three

lower voices take on

the existing

instrumental motifs

and develop them

further. In the

fourth line (“Des

freuet sich der

Engel Schar” –

“for which the

Angelic Host

rejoices”) attention

is drawn to how

lively is the joy of

the Angelic Host.

No. 2 is a Recitativo

for soprano

and basso continuo,

which, as already

mentioned, includes

the second stanza of

Luther’s hymn,

framed by new

additional verses

from the Baroque

poet. As in many

similar cases (the

process was familiar

to Bach), it is made

clear in the

composition which

are the new and

which are the old

lines. Bach sets the

Luther quotations to

the old Chorale

tune, which he

treats

contrapuntally (the

basso continuo plays

the repeated

fragment of the

Chorale twice as

fast as it occurs in

the hymn and at

differing pitches).

In contrast, the new

verses are treated

in a free secco

style. The Chorale

text and the newer

commentary by the

poet form a Baroque

to and fro, which

very skilfully

combines the old and

the new (the Kyrie

eleison of Luther at

the end of each

verse is omitted

here).

No. 3 is an Aria

for tenor with

the three oboes and

basso continuo,

whose text is a

reworking of the

third and fourth

verses of Luther’s

hymn. The new text

has two parts (A and

B) each of three

lines belonging

together, which Bach

repeats as a mirror

image (AB / BA). The

piece sounds like a

kind of chaconne,

with its typical

dotted rhythm. Bach

took inspiration for

the material of the

motif from the first

line: “Gott, dem

der Erden Kreis zu

klein…” (God,

for whom the earth

is too small ...).

The dotted oboe

motif in the opening

bars (in canon with

the three following

each other) is

directed to the

heavens (upward),

but the similarly

dotted reply of the

continuo in the

second bar points

downward – the

combination of the

two is surely Bach’s

suggestion of the

“All” of the earth,

which for God is too

small. In a charming

Baroque contrast to

this is the third

line: “(dieser

Gott) will in der

engen Krippe sein”

(this God) wants to

be in the narrow

manger). Likewise,

the tenor soloist

takes over the

expressive motifs of

the oboes (in which

his own

embellishment upward

to heaven should be

noted!). At the

start of the second

part the tenor sings

“Erscheinet uns

das ew’ge Licht…”

(to us appears the

eternal light...),

these words

naturally set to a

descending scale.

The light shines

down from on high,

and at the same time

the three oboes

interject short

phrases, clearly

illustrating brief

flashes of light.

The word “ew’ge”

(eternal) is

illustrated by a

long sustained note

for the voice.

During the last

repetition of the

second line, just as

reasonably, there is

a long emotional

vocalise on “fassen”

(to hold)

(suggesting the

“embrace” here).

This aria again

shows Bach’s

absolute mastery of

text treatment – so

penetrating and

refined, yet still

so understandable

for the less

specialized

audience.

A recitativo

accompagnato for

bass and

strings follows this

(No. 4),

which reworks the

fifth verse of

Luther’s hymn. It is

an official call to

Christendom to

welcome the Creator.

(It is assigned to

the bass, in order

to emphasize the

paternal authority

of the Church?).

Where the poet

writes, “er

kömmt zu dir um

dich für seinen

Thron / Durch

dieses Jammertal

zu führen” (He

comes in order to

lead thee to His

Throne / through

this vale of tears),

Bach gratefully

takes the

opportunity to

develop this latter

line as a complex

chromatic web in

adagio tempo (“Jammertal”

– “vale of tears”!);

what is remarkable

is how, despite all

the sadness, the

main movement is

upwards, where God’s

Throne is to be

found!

There follows a Duet

for soprano and

alto with all

the violins in

unison (No. 5):

a reworking of

Luther’s sixth

verse: “Die

Armut, so Gott auf

sich nimmt / Hat

uns ein ewig Heil

bestimmt” (The

poverty, which God

assumes, / hath

ordained an eternal

salvation for us).

Into this movement

also Bach has woven

a great and

eloquently beautiful

richness, which

reveals how

devoutly, how

profoundly he

considered his text

from every angle, in

order to make it

musically

comprehensible. The

basso continuo

presents a steady Andante-Bass

(the eternal course

of time!): striding

quavers support the

entire structure.

The violins play

almost endlessly a

repetitive dotted

rhythm, which

probably indicates

the hard, laborious

life of Jesus (the

poverty that God “auf

sich nimmt ohne

Unterlass”

(assumes without

respite)). That

there are two voices

singing in duet

provides several

opportunities to

illustrate the

symbolism of the

text. In the first

place it illustrates

quite simply the

plural form (“…hat

uns ein ewig Heil

bestimmt”

(...hath ordained an

eternal salvation

for us)). The layout

also makes possible

fascinating and

harmonious frictions

between the two solo

parts, which are in

accordance with the

text (for example

the plaintive

dissonance between

the two voices on “Armut”,

both at the

beginning and again

later). Also the

opposite, as a

contrast, perfect

peaceful harmony is

illustrated by

thirds and sixths

(for example on “ein

ewig Heil” (an

eternal salvation)

or on “ein

Überfluss an

Himmelsschätzen”

(a profusion of

Heaven’s gifts)).

This duet is even

more eloquent in the

B-part of the aria,

where the notation

really illustrates a

theology. The poet

now addresses the

faithful directly

and tells them: “Sein

(Jesu) menschlich

Wesen machet euch

den

Engelsherrlichkeiten

gleich / Euch zu

der Engel Chor zu

setzen” (In

taking human form He

(Jesus) makes thee

like the glorious

Angels / placing

thee in the Angelic

choir). This double

nature (man compared

to angels) is

suggested by the

same two voices: the

human beings on the

one hand are

depicted in the

soprano by shaking

syncopations and at

the same time in the

alto are

characterised by a

slow rising

chromatic line. This

line undoubtedly

points to the rise

of human beings

towards angelic

glory, from which

the words come; then

both the separate

lines alternate

between the two

voices. Angelic

glory always has a

rising semiquaver

line. In this B part

of the aria the

dotted rhythm

ostinato in the

violins is sometimes

dropped, and is even

now and then

transferred to the

basso continuo.

Further changes

also occur in the

parts: as, for

example, the

ascending chromatic

line is found in the

violin part and in

the basso continuo.

Another feature is

that, in the course

of the B-part, Bach

uses the vocal

beginning of the A

section again, but

with the B-text.

A simple chorale

(No. 6) on the

original text of

Martin Luther’s

seventh verse closes

this

wellproportioned

cantata. As a last

feature it should be

noted how Bach

includes the two

horns and timpani –

initially discreet,

but, in the final

Kyrie eleison, with

a strikingly festive

and ornamented

figure (pointing

upwards!).

“Selig ist der

Mann”, BWV

57

(Blessed is the

man)

This work was

written for the

Second Day of

Christmas 1725. The

26th December is

also the Feast of

St. Stephen, the

first martyr of the

church. As we read

in the Acts of the

Apostles, he was

stoned to death. The

text of the Cantata

BWV 57 deals with

this theme of

martyrdom, thus it

is not connected

with the Christmas

story.

The cantata is

written for two

soloists (soprano

and bass), who take

part in a dialogue

as the soul and

Jesus (as also, for

example, in Cantata

21 “Ich hatte viel

Bekümmernis” (I had

much distress). Only

in the simple final

chorale is the full

vocal quartet

required. The

instrumentation

consists of two

oboes and taille

(alto oboe) with

strings.

The text of this

Cantata is by G.

Chr. Lehms

(1684-1717), who

wrote texts for

several annual

cantata cycles,

which were set by

composers such as J.

Chr. Graupner, among

others. “Selig

ist der Mann”

comes from Lehm’s

1711 annual cycle.

No. 1 is an Aria

for Basso with

all the instruments

– so there is no

opening chorus.

Lehm’s libretto

begins with a

quotation from the

Epistle of James (1,

12): “Selig ist

der Mann, der die

Anfechtung

erduldet; denn

nachdem er

bewähret ist, wird

er die Krone des

Lebens empfangen”

(Blessed is the man

that endureth

temptation: for when

he is tried, he

shall receive the

crown of life). This

fragment is actually

very appropriate for

the story of

Stephen, and we can

understand Lehm’s

choice in starting

with it. That Bach

sets this text for

bass solo can be

compared with other

passages in other

cantatas, where the

bass clearly

represents the VOX

DEI. God’s voice

does not actually

speak directly here,

but the Epistle of

James, as part of

the Scripture, still

has a Divine

Authority, which is

traditionally

entrusted to a bass

(the archetype of

the Good Lord with

the long beard, in

Heaven?).

The key is G minor –

the key of the

deep-felt passion,

the unimaginable

abyss. Die – rather

than give into

temptation: that is

the profound power

of martyrdom. The

movement has a

five-part fabric:

the four

instrumental voices

and the bass soloist

are completely

equal. Bach would

not be Bach, if he

did not let the form

of his motifs be

determined by the

text. The term ‘Anfechtung’

(temptation) gives

rise to the opening

motif, which is

repeated in the

upper voices three

times consecutively,

answered immediately

as a mirror image in

the basso continuo.

The repeated and

simultaneous reuse

of the two

contrasted forms of

the main motif (the

original and its

mirror image)

clearly indicates

the antithesis, the

conflict – what is

temptation other

than an inner

conflict?

Other rhetorical

beauties of this

aria are the long

sustained notes on selig

– bewähret –

erduldet

(saved – tried –

endured), which time

and again suggests

the duration. At the

end of the

instrumental

introduction,

incidentally, this

sustained note had

already been heard

in the basso

continuo, in

combination with a

plaintive, downward

chromatic line in

the upper voice (the

pain of martyrdom?).

This combination, by

the way, is

occasionally

repeated later. The

setting of the word

‘Krone’

(crown) for the last

time, shortly before

the end, is

intentionally vivid.

A Recitativo

secco (No. 2)

follows for soprano,

“the soul” (Anima).

She is oppressed, “findet

im Ach und Schmerz

(ihr) ewig’s

Leiden” (she

finds in lamentation

and grief (her)

suffering for ever).

Lehms cleverly added

his lines to some

quotations from St.

Matthew (with the

“rauen Wölfen”

(savage wolves) and

with the “recht

verlassnes Lamm”

(quite abandoned

lamb)). In the

absence of the

consolation of

Jesus, sings the

Anima, “So

müsste Mut und

Herze brechen/und

voller Trauren

sprechen” (so

must my courage and

my heart break / and

I sing full of

sorrow):

With this colon, the

No. 3 in the

libretto is

introduced, a Soprano

Aria with

strings, in which

the Anima continues

her previous

thoughts: “Ich

wünschte mir den

Tod / Wenn Du,

mein Jesus, mich

nicht liebtest”

(I would wish to die

/ if Thou, my Jesus,

loveth me not).

Musically, this aria

is the

counterweight, or

rather the parallel

piece, to the bass

aria (No. 1, G

minor): the same

tempo, as well as

the ¾ time. The main

emotion here is

clearly the sadness

and the longing (I

wish to die) – hence

the choice of the C

minor key.

In addition, this

aria is a model of

pure five-part

writing, but a

thematic separation

remains between the

instruments and the

soprano: the main

motif of the

instruments at the

beginning is never

sung by the soprano

(Anima) –

illustrating both

the isolation, and

the loneliness of

the unhappy soul ...

The main

instrumental motif,

as it is heard in

the first violins at

the beginning,

corresponds entirely

to the words, not

yet spoken, “Ich

wünschte mir den

Tod” (I would

wish to die): a

rising line in the

first bar (the

hopeful wishes),

then an abrupt fall

downwards (the

death?). This image

is repeated

continuously, in the

basso continuo as

well. When, finally,

the Anima herself

sings these words,

the picture is less

clear: it is indeed

only conditional (“ich

wünschte mir… wenn

nicht...” (I

would wish ... if

not ..)), they do

not indicate the

conclusive reality.

At the beginning of

the B-part the basso

continuo, which so

far has been limited

to a quiet quaver

figure and an

andante bass still

indicating the

duration, is

suddenly more

active. It pushes

itself forward with

versions of the

violin motif from

the opening bars.

Meanwhile, the first

violins are in

parallel with the

Anima “Ja, wenn

du mich annoch

betrübtest”

(Yes, if Thou still

makes me sad). The

aria ends with a

repetition of the

A-text, but the

setting is not

identical.

A short Recitativo

secco for duet

(No. 4)

follows, in which

Jesus (bass) extends

hand and heart to

the unfortunate soul

‘die Hand und das

Herze anreicht’ –

to which the soul,

deeply soothed and

grateful, replies: “Ach,

süßes Liebespfand

/ Du kannst die

Feinde stürzen /

Und ihren Grimm

verkürzen”

(Ah, sweet pledge of

love / Thou can

bring down the

enemies / And

shorten their

wrath).

In the following Aria

for the Bass

and strings (No.

5) Jesus is

portrayed (as the

soul has already

announced) as one

who, in the battle,

can vanquish the

enemies, who always

proceed against the

soul. Stylish

martial music in the

A-section of the

aria suggests this

quarrel to us: a

trumpet-like motif

in repeated

semiquavers springs,

to and fro, from the

violin parts and the

basso continuo. In

the B section of the

text, however, this

battle motif

disappears

altogether. Here

slower sighing

figures

(appoggiaturas)

predominate, “Bedrängter

Geist, hör auf zu

weinen” (Cease

crying, afflicted

soul) in accordance

with the text. The “Kummerwolken”

(clouds of

sorrow), which will

disappear soon, are

aptly described in a

four-part

instrumental fabric

consisting of

horizontal lines

entering

canonically. The

painter Bach

overlooks nothing...

In the Recitativo

Duet (No. 6)

with basso continuo

the dialogue between

the soul and Jesus

is terminated. Jesus

promises the soul

eternal rest and

life. She responds

to these words with

a long impassioned

monologue, in which

she sings of her

longing for that

life after death in

vivid language: “Ach,

striche mir der

Wind schon über

Gruft und Grab”…

“Wohl denen, die

im Sarge liegen

und auf den Schall

der Engel hoffen”…

(Ah, the wind

strikes me already

over tomb and grave

... Happy are those

that lie in their

coffin, and hope to

hear the sound of

angels ...)

In this eager

expectation, the

soul (soprano)

continues in the

subsequent Aria with

solo violin and

basso continuo (No.

7): “Ich ende

behende

mein irdisches

Leben”

(I swiftly end my

earthly life) (note

in the text the

dactylic Amphibrach

foot:

short-long-short in

constant

repetition!). This

aria, in its

apparently relative

simplicity,

contains, on the

other hand, numerous

masterly features.

Bach transformed the

binary character of

the text into a

stirring fast triple

time, similar to a

passepied, wholly in

keeping with the

feeling that is

alive here in the

Anima. The solo

violin part

initially displays,

not by chance, a

downward movement:

the end of life,

‘down to death’. The

rest of the violin

part alternates

between rather

circular movements

and the downward

movement already

described. When the

Anima enters, it is

remarkable how her

singing expresses a

certain

indifference; death

does not deter her,

quite the opposite.

With all this joy

(actually more the

anticipation of joy)

the key is

nevertheless still G

Minor (the agitato

key, the hidden

abyss – as we have

already seen at the

beginning of the

Cantata). Bach

paints his words

carefully: for “Freuden”

(joy) there is

always an ascending

interval or a longer

rising line; on the

other hand, on “Scheiden”

(to depart) the

movement is

downwards. On “verlang”

(yearn) there is a

long held note (the

duration,

repeated!),

sometimes a more

complex portrayal.

In the B section of

the aria the violin

plays its earlier

motifs again, but

the Anima imitates

(almost carelessly)

a few times, on “ich

sterbe” (I’m

dying), the

dying-affekt in a

short, almost

plaintive

interjection; it

culminates, finally,

on the question of “was

schenkest Du mir?”

(what givest Thou

me?) now that I am

giving myself to

Thee? Here the

little word “was”

(what) is used very

effectively as an

isolated

interjection. The

aria ends by analogy

with this abrupt

question mark.

An answer to this

question is not

given directly,

rather it can be

distilled from the

following closing Chorale

(No. 8). Here

Bach has intervened

in Lehms’s libretto:

he did not set the

final Chorale text

provided by Lehms,

but chose another

Chorale (by

Ahasverus Fritsch,

1668), which

connects more

clearly with the

question in the last

aria. It is a

Chorale in a joyous

triple time “Richte

dich, Liebste,

nach meinem

Gefallen…“

(Depend, beloved, on

my pleasure ...).

“Süßer Trost,

mein Jesus kömmt“,

BWV 151

(Sweet comfort,

my Jesus comes)

This cantata was

heard in 1725 on the

first day after the

St. Stephen cantata

(BWV 57) discussed

above, that is the

27th December, the

third day of

Christmas. As with

BWV 57 Bach took the

text from Lehms

annual cycle of

1711.

Here we are again

totally in the

Christmas

atmosphere. The

transverse flute and

the oboe d’amore

represent the

shepherds and the

rural life of

Bethlehem (think of

the numerous

paintings from the

Baroque period).

The No. 1 is

a Soprano Aria,

beginning in 12/8

time, which Bach has

marked Molt’adagio.

We hear a kind of Siciliano,

very stylized and

introverted. The

flute delights in

meditatively playing

around with the

melody, which will

be sung later by the

soprano. The oboe

d’amore quietly

doubles the first

violins, which, in

parallel thirds and

sixths with the

second violins and

viola, conjure up an

idyllic, very

‘Christmassy’

harmony, discreetly

supported by some

bass notes.

Sometimes it happens

that the improvising

flute and the upper

line come together

in a moving unison,

in which even the

basso continuo

becomes lyrical and

adds to the rural

ambiance. The Text

by Lehms: “Süßer

Trost, mein Jesus

kömmt / Jesus wird

anitzt geboren!

...” (Sweet

comfort, my Jesus

comes / Jesus is

born today!...) is

put in the mouth of

the soprano, so that

we think

instinctively of the

Virgin Mary, though

here it is not the

pregnant woman about

to give birth, but

rather the eternal

Mother of God, who

is astonished by her

motherhood, and

gratefully thinks

about and enjoys it.

At the same time, in

the context of

Christian mythology,

these thoughts

should also live at

the heart of

Christendom;

gratitude for the

comfort, which the

Christ Child brings

us.

With the B-part of

this aria the

character changes

completely. Lehms

writes: “Herz

und Seele freuet sich

/ Denn mein

liebster Gott hat

mich / Nun zum

Himmel

auserkoren”

(Heart and soul

rejoice / For my

dearest God / hath

now chosen me for

Heaven), and Bach

appropriately marks

the score Vivace.

Instruments and

voices scan this new

text, and the

soprano launches

into a suitable

vocalise on “Freuet”

(Rejoice), which is

immediately taken up

by the flute. So

both compete in

joyful figures, in

which the flute, in

an ascending

passage, points to

the word “Himmel”

(heaven). The da

capo of the A-part

brings us back again

into the earlier

meditative world of

the beginning.

There follows (No.

2), a Recitativo

secco for bass,

in which the

listener finds

explained the whole

theological

background to the

theme – what the

birth of Jesus

means, or should

mean, for the

Christian. In the

last line it is

summarized as

follows: “Gott

wird ein

Mensch und will

auf Erden / Noch

niedriger als wir

und noch viel

ärmer werden”

(God becomes a man

and intends on earth

/ to become both

more humble than us

and much poorer).

In the following Aria

(No. 3) for

alto with oboe

d’amore and strings,

it is striking how

the melodic line of

the main motif time

and again is placed

in the low levels,

how the line

repeatedly points

downward (the

humiliation!) until

on the word “Trost”

(comfort) it

suddenly goes

upwards. Bach

achieves, in this

rhetorical manner, a

discreetly increased

and ideal unity

between the

fragments, which

follow one after the

other. This aria is

a long, constantly

developing Andante,

through which the

feeling for the time

is expressed

intensely, and thus

for the steady

progress of human

life, which should

be lived with

Christian composure.

Blessings will come

– as promised by the

poet – from poverty

and humility, whose

heavy burden Bach

almost makes us feel

physically through a

certain monotony and

the long duration of

the aria.

The tenor

then concludes with

a simple brief word

of thanks (Recitativo

Secco, No. 4):

“Weil du nun

ganz allein des

Vaters Burg und

Thron aus Liebe

gegen uns

verlassen / So

wollen wir dich

auch dafür in

unser Herze

fassen” (Since

for love of us alone

Thou left the

Father’s mansion and

throne / So we also

wish to take Thee

into our hearts).

The cantata ends

with a simple

four-part Chorale

(No. 5). It is

the eighth Verse of

“Lobt Gott, ihr

Christen

allzugleich”

(Praise God, ye

Christians all

together) by N.

Hermann, 1560. The

basic idea here is

that God, through

the birth of Jesus,

has unlocked the

gates of paradise

again (“der

Cherub steht nicht

mehr dafür”

(the guardian angel

stands there no

more) – so it is

said briefly and

vivdly in the third

line of this verse,

to indicate that

entry is now free

for the devout

Christian).

“Das neugeborne

Kindelein”,

BWV 122

(The little

newborn Child)

It was on the 31st

December, the First

Sunday after

Christmas in 1724,

that this Chorale

cantata was heard.

The text of the

four-verse hymn by

Cyriacus Schneegass

(1597) combined the

Feasts of Christmas

and New Year: ”Das

neugeborne

Kindelein /

Das herzeliebe

Jesulein / Bringt

abermal ein neues

Jahr / Der

auserwählten

Christenschar”

(The little newborn

Child / The beloved

little Jesus /

brings in once again

a New Year / for the

throng of Chosen

Christians), it says

right away in the

first verse.

The author of the

text, who extended

this short hymn with

his own lines, has

remained unknown,

but he has retained

verses 1 and 4 (that

is the first and

last of the

original) for nos. 1

and 6 of the Cantata

texts. The third

verse of the old

hymn he used as no.

4 of the Cantata,

and added his own

lines to it. He has

rewritten the second

original verse, and

used it in the

second and third

movements of the

Cantata as a basic

idea – though then

combined it with the

theme of the Fall of

Man from the Old

Testament, which (as

A. Dürr has noted)

is often found in

Christmas texts.

Movement 5 of the

Cantata is newly

written, but

inspired by the

closing verse of C.

Sneegass, 1597.

Missing in this

cantata text is any

direct reference to

the lessons for that

Sunday – a fact

which we find quite

rarely in Bach’s

cantatas.

Bach has set this

cantata for 2 oboes,

taille (alto oboe)

and strings, but we

must remember again

that at the time

oboes were

particularly used as

‘shepherd’s

instruments’, and

that Christmas and

shepherds are

closely linked with

each other in our

tradition.

The Cantata begins

with a Chorus

(No. 1), in

which all the

instruments take

part. In the 15-bar

instrumental

introduction a motif

is presented, which

is completely

independent of the

old Chorale motif,

and remains so; the

latter is always

sung in the soprano

with long notes (as

is often the case),

while the three

lower voices use a

motif derived from

the Chorale in a

free contrapuntal

style. The G minor

key stands in this

case for an

inward-looking yet

active joy; the

original Chorale

melody is in triple

time (as we meet

again in the final

Chorale). The

opening movement

maintains this

lively character.

The result is an

overall light

dancing affekt (like

a Menuet /

Passepied).

The four lines of

the original verse

are performed in

four distinct

“blocks”, each

alternating with

instrumental

interludes. Each

line has its own web

in the lower voices.

In the last verse

the bass develops an

extended vocalise on

the word “Christenschar”

(throng of

Christians): an

illustration of the

diversity, the size

of the throng?

The following Aria

for Bass (No. 2)

with only basso

continuo is a pure

Bicinium for two

deep parts, one of

which is sung, but

the other is played.

The text is like a

definite exhortation

from God. That is

why Bach has used

the bass voice here,

as it were the VOX

DEI, even if the

text is not verbatim

from the scriptures.

The affekt is

strong, because the

poet puts words in

the mouth of God.

Man sins daily, but

he should still have

had to give joy to

the angels, since

they have announced

the divine comfort

of the

reconciliation. The

composition is

impressive in its

complex two-part

texture, in which

the instrumental

bass forms the

wordless support,

above which the Vox

Dei can distinguish

itself.

After this

particular piece

there follows an

equally unique and

contrasting

fragment: a Recitativo

accompagnato for

soprano (No. 3)

with three high

recorders and basso

continuo (The

recorders were

probably played by

the three oboists).

As in the preceding

movement where a

strong judgment is

heard from the

depths, here we are

surprised from the

heights, through the

message (from the

soprano), that the

angels now rejoice

with us over our

salvation. God has

again opened

Paradise to us,

after he had

expelled us from it;

for this we should

also be grateful.

The soprano sings

the lines in a

flowery recitative

style, during which

the Chorale melody

is heard clearly

from the highest

recorder, supported

closely by the other

two in “close

harmony”, truly the

angel choir singing

for us.

There follows a Trio

(No. 4) for

soprano, alto and

tenor (with

violins and viola in

unison) – all

supported by an

endless repetitive

motif in the basso

continuo (roughly

equivalent to an

English Ground,

familiar to us from

the seventeenth

century). The

character of this Ground

is similar to a

Siciliano. As Alfred

Dürr correctly

points out, Bach

deliberately used

the middle pitch

register after he

had, in the two

previous numbers,

symbolically used

the low and high

registers (in the

bass Bicinium, No.

2, as the voice of

God, whereas the

soprano in No. 3, is

‘accompagnato’ with

recorders, the

singing of angels).

In fact, in this

passage the

connection between

high and low is

established: God

(the Infant Jesus)

has become a man,

who can now even

fight against the

devil. This all

takes place in the

middle – of our

life.

Exactly as it

appears in the text,

we also find two

levels musically

combined with each

other. As mentioned,

the poet has used

the four original

lines of the third

verse verbatim, but

has also composed

four new lines in

the same metre.

Soprano and tenor

sing this new text

and thus form a

perfect duet,

supported by the

basso continuo. To

this the alto,

doubled by the

violins and viola,

adds clearly

separate sections of

the old Chorale text

with the original

melody, and

transforms the duet

into a trio at these

points. As the old

Chorale verse

displays a formal

entity (with each

pair of lines

rhyming as usual and

with their own train

of thought), so does

the new text. Here

the rhyme is

similarly formed,

and the lines follow

one another with an

inner logic.

Alongside the first

new line (in the

soprano and tenor)

the alto still sings

the first line of

the old Chorale

verse, in which the

newly composed line

always explains the

old line, heard at

the same time.

Similarly, the

second, third and

fourth lines are

each combined in the

poem. Both the old

and the new text

express confidence

in the protection of

God (the Infant

Jesus).

The following Recitativo

accompagnato (No.

5) for bass

and strings is an

added text by the

Baroque poet,

inspired by the

fourth (thus the

last) Chorale verse,

which will follow

verbatim later as

the end of the

cantata. With its

exclamation “O

... etc”

repeated five times,

this poem seeks to

achieve the effect

of worship. It

springs from the

poet’s own feelings.

The old Chorale

texts are generally

less subjective,

they are directed to

the community with

more collective

thoughts. We follow

Bach’s ornaments on

“O sel’ge Zeit”

(O blessed time),

and the important

role of the strings,

for example with the

harmonic tension on

“Trübsal”

(sorrow), and the

beautiful variation

at the end, after “und

Gott der Lippen

Opfer bringt!”

(and bring God

offerings from our

lips).

The poet achieves

some particularly

successful phrases

in this fragment:

for example “O

Glaube, der sein

Ende sieht” (O

faith that sees its

end): that faith,

which even from the

beginning is mostly

asked or almost

demanded from us by

others, can be ended

here, since we now see

that the Son of God

came to us (in other

words, what one can

see, perceive one

must no longer

accept as faith!).

As a poetic picture

this line has a

direct effect, and

here I must allow

myself a personal,

continuing thought,

which is important

to me, though it

comes outside the

actual framework of

the Cantata text.

Quite generally, for

people trying to

understand the Mystery

of the Existence,

it is (in my

opinion) a release

no longer to have to

understand this

mystery so much as a

faith, and then have

to be dependent on

this ‘faith’, as

long as it still

finds the strength

in the heart to

survive. It is

sufficient to open

ones eyes to take in

the truth, to see

how this mystery of

life is visibly

present in the

smallest as in the

largest phenomenons

in this world, and

how it is at the

root of everything.

“Your faith will

save you” (as many

religions preach

time and again), but

rather it becomes

clear how other,

more personal ways

lie open to the

experience, if we

want it ... (but of

course such thoughts

probably played no

rôle for Bach as one

of the devout

Lutherans of his

time.)

The Chorale (No.

6) is, as

already mentioned,

the final verse of

the old hymn, set

simply in four parts

for all the

participants: an

inwardly joyful song

in triple time,

completely

appropriate for the

Christmas-New Year

period.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|