|

|

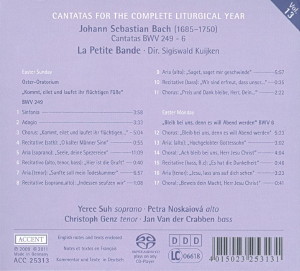

1 CD -

ACC 25313 - (p) 2009

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25313 - (p) 2009 - rectus

|

|

CANTATAS -

Volume 13

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oster-Oratorium (Easter

Sunday)

|

|

|

|

"Kommt, eilet und

laufet ihr flüchtigen Füße", BWV

249

|

|

42' 18" |

|

| -

Sinfonia |

3'

58"

|

|

|

| -

Adagio |

3' 33" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Kommt, eilet und

laufet ihr Flüchtigen Füße |

5' 04" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano, alto,

tenor, bass): O kalter Männer Sinn |

0' 55" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Seele, deine

Spezereien |

11' 09" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto, tenor,

bass): Hier ist die Gruft |

0' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Sanfte soll

mein Todeskummer |

6' 57" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano, alto):

Indessen seufzen wir |

1' 08" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Saget, saget mit

geschwinde |

5' 57" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Wir sind

erfreut |

0' 35" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Preis und Dank |

2' 22" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Osterfesttag (Easter Monday)

|

|

|

|

| "Nleib bei uns,

denn es will Abend werden", BWV

6 |

|

16' 43" |

|

| -

Chorus: Bleib bei uns, denn

es will Abend werden |

5' 23" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Hochgelobter

Gottessohn |

3' 02" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ach bleib bei uns,

Herr Jesu Christ |

4' 04" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Es hat die

Dunkelheit an vielen Orten |

0' 46" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Jesu, lass uns auf

dich sehen |

3' 23" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Beweis dein Macht,

Herr Jesu Christ |

0' 41" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yeree Suh, soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I, violoncello da spalla

|

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Annelies Decock,

violin I |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Ann Cnop, violin

II

|

|

|

- Masanobu Tokura,

violin II

|

|

|

- Sara Kuijken, violin

II |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Michel Boulanger,

basse de violon |

|

|

- Jean-François

Madeuf, tromba |

|

|

- Jean-Charles

Denis, tromba |

|

|

- Graham Nicholson,

tromba |

|

|

- Koen Plaetinck, timpani |

|

|

- Frank Theuns, transverse

flute, recorder

|

|

|

- Ann Vanlancker, recorder,

oboe

|

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe, oboe d'amore |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe da caccia, oboe d'amore |

|

|

- Rainer Johannsen,

bassoon |

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Academiezaal,

Sint-Truiden, (Belgium) - 23/27

April 2009

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25313 - (1 CD) - durata 59'

00" - (p) 2009 (c) 2011 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

This

recording contains

works for Easter

Sunday (BWV 249) and

Easter Monday (BWV

6). BWV 249 and BWV

6 come from the same

annual cycle (1725).

The Leipzig

congregation heard

these two pieces for

the first time on

two consecutive

days. Only BWV 6,

“Bleib bei uns, denn

es will abend

werden” (Abide with

us, for evening

approaches) was

intended by Bach to

be a church cantata.

The other work goes

back to cantatas for

secular occasions

and shows us in an

exemplary way the

skill of Bach and

his text poet at

remodelling

(parody).

EASTER ORATORIO

“Kommt, eilet

und laufet, ihr

flüchtigen Füße”,

BWV 249

(Come,

hurry and run, on

your flying feet)

(Easter Sunday,

1725)

The original secular

source for the

Easter Oratorio (BWV

249a, “Entfliehet,

verschwindet,

entweichet, Ihr

Sorgen” - Flee,

disappear, escape

your cares) was

heard five weeks

before Easter 1725,

as the “Shepherd

Cantata” (Pastorale)

for the birthday of

the Duke Christian

von

Sachsen-Weissenfels.

On Easter Day of the

same year, the 1st

April, 1725, the

church version of

this Pastorale was

performed: the

Easter Oratorio.

The poet Picander,

who worked closely

with Bach, was the

author of both

versions.

The Easter Oratorio

was first given the

title “Oratorio” by

Bach himself for a

repeat performance

in the 1740s. It

differed from the

other Bach-Picander

Oratorios in that no

Evangelist appears

here to perform the

Gospel sections, and

also there are no

chorales.

The Pastorale (BWV

249a) for Duke

Christian was based

on a tradition,

which had its origin

in antiquity and was

handed down via the

Renaissance.

“Shepherds” act out

a scene, which is

appropriate for a

celebration. The

form is one of a

small opera, with

alternating

recitatives, arias

and ensembles.

(Pieces of this kind

can be presented

with a minimum of

scenic means, or

even performed just

with conventional

gestures.)

With the reworking

of the Shepherd

Cantata into the

sacred Cantata the

structure and also

the musical

composition of the

work remain

unchanged. The new

libretto was so

written that in each

fragment the prosody

of both versions is

parallel, and thus

the existing music

of the first version

fits seamlessly.

Naturally the

recitatives were

newly composed. The

four shepherds of

the original

Pastorale became

four holy

characters: Maria

Jacobi (soprano),

Maria Magdalena

(alto), and the

Apostles Peter

(tenor) and John

(bass).

The original

“Shepherd Play” thus

became at Easter an

“Easter Play”. At

that time it was

also in fact

traditional, in the

Easter church

service, for the

holy characters

sometimes to come on

to the stage, where

they ‘perform’, as

they approach the

sepulchre and

discover with

astonishment that it

is empty. Was Bach’s

work also performed

in this way? For me

I don’t know of any

indication for this.

Possibly (or even

probably, in this

case) Bach and

Picander at the

outset considered

that the form of the

original Pastorale

should be

‘compatible’ with

the sacred parody

five weeks later. If

this is so (which I

accept), the text

and musical setting

were conceived in a

kind of ‘double

bookkeeping’, as a

joint exercise. Such

‘mix-and-match’

invention is the

most amazing

achievement, which

shows how, at the

time, artistic

‘craft’ and

technical ability

were developed and

also treasured so

highly. We are here

far removed from the

idea of a rather

spontaneous,

individualistic

artist, who wishes

to divulge to the

public all the most

personal emotions

for the sake of

their egos... Also

the frequently

occurring parodies

of this kind from

the ‘secular’ to the

‘sacred’ testify

that, in Bach’s

time, there was not

such a distinction

between the two.

Incidentally, a year

later (1726) Bach

and Picander wrote a

third work as a

parody of the

original Pastorale:

the secular Cantata

”Verjaget,

zerstreuet,

zerrüttet ihr

Sterne” (Dispel,

scatter, destroy

them, you stars),

likewise for a noble

birthday. Sadly,

however, this score

has gone missing.

Very clearly the

intention in the

Easter Oratorio was

not so much to

present the Gospel

text literally with

appropriate

commentary, but much

more to perform a

kind of devotional

event within a

traditional

framework, in order

to strengthen the

religious ideas of

the believers and

their faith. The

aspect of

‘catechesis’ is

always present as

well!

Both versions

display a festive

instrumental

setting, and begin

with instrumental

music, which is like

a concerto.

The Sinfonia

(no. 1) is for

three trumpets and

timpani, two oboes

and bassoon, strings

and basso continuo.

This instrumentation

was very typical for

festive occasions,

both sacred and

secular.

This Sinfonia in 3/8

time was most

probably once the

first movement of an

instrumental

concerto. Bach uses

the sound colours of

the different

families of

instruments very

skilfully, which

also on occasion,

split up into

‘individual

families’, to show

off their typical

colours.

There follows an Adagio

(no. 2): the

second movement of

the concerto? The

trumpets, timpani,

oboes and the

bassoon are silent,

and one of the

oboists takes up the

transverse flute (a

quite natural thing

at the time). This

movement has a

completely different

feeling. The flute

plays a highly

decorated lyrical

line, supported by

the strings, which

bear the harmonic

changes with a

repetitively

repeated rhythmic

figure. This Adagio

ends with a

‘question mark’ in

the music, to which

the next movement,

so to speak,

provides the answer:

No. 3 is a

rearrangement of the

presumed finale of

the concerto – and

at the same time the

actual Opening

chorus of both

versions of the

work. Here the four

protagonists make

their appearance,

who call to each

other – and in a

figurative sense to

everyone – to hurry

to the grave of

Jesus “for our

Saviour has risen

from the dead”. So

this is a kind of

prologue to the

action. In the first

version of the

sacred Cantata

(1725), this

fragment was a duet

between Peter and

John; in a later

performance Bach

decided to let the

two women to take

part as well, which

presents no problem

for the text. We

have used the later

version.

The movement has an

A-B-A form, and the

tempo is similar to

a Passepied; after

24 bars of cheerful

introduction the

voices enter, with

the instruments

participating more

modestly. The

figures on “eilet –

hurry” and “laufet –

run” are very

appropriate. In the

B-part, (“Lachen und

Scherzen begleiten

die Herzen, denn

unser Heil ist

auferweckt” -

Laughing and joking

accompany our

hearts, for our

Saviour has risen

from the dead), only

Peter and John sing,

with a reduced

accompaniment, in

which “Lachen”

receives an

appropriate

semiquaver figure,

and on “Heil” both

sing a long

vocalise.

As an example of the

parody process, I

make here a short

comparison between

the secular version

of the B-part and

the sacred

reworking, in order

to illustrate how

well the poet can

supply a new text

for the existing

music. The Pastorale

text says “Lachen

und Scherzen /

Erfüllet die Herzen

// Die Freude malet

das Gesicht”

(Laughing and joking

/ fills our hearts /

our face is a

picture of joy) –

the metre in the

first two lines is

dactylic in

character (‘dactyl’

– long short short.

long short short

etc. and

‘amphibrach’ – short

long short, short

long short etc.) and

in the third line

iambic (short long,

short long etc.).

The reworking

respects this

introduction

exactly: “Lachen

und Scherzen

/ Erfüllet

die Herzen

// Die Freude

malet das

Gesicht”.

In the following Rezitativo

secco (no. 4),

in Baroque fashion,

the two Marias are

placed opposite the

two Apostles. The

women reproach the

men for a certain

unloving nature.

They had not hurried

to the sepulchre as

early as the women,

who had to go first

to set a good

example (we also

read in the Gospel

account, that the

women had run there

first). The two men

defend themselves by

saying that they,

meanwhile, had from

their tears for

their Saviour (after

his Crucifixion)

intended an

annointing for his

body, “which (as the

two Marias replied)

is now in vain

because He is risen”

... Here, therefore,

to the delight of

the faithful the

gospel account is

treated in a relaxed

way.

The Aria (no. 5)

for soprano (Maria,

the mother Jacobi),

transverse flute and

basso continuo, adds

to the idea of the

annointing, which

had just been

expressed by the two

men: “Seele, deine

Spezereien sollen

nicht mehr Myrrhen

sein…” (My soul, thy

spices should no

more be myrrh) – the

soul now should

rather bring laurel,

the symbol of

victory. Jesus has

triumphed through

his resurrection! In

this aria the flute

plays in dialogue

with the soprano the

‘fragrance of

spices’ in elegant

figures.

The

same piece in the

original Pastorale

had a text, in which

the shepherdess

Doris declares that

she can no longer

withhold “the

hundred thousand

flatteries which

well up in her

breast”. She wants

to run to the

Goddess Flora to ask

her to bind a wreath

for Duke Christian’s

birthday, (as it is

still winter and

nature has produced

no flowers ...).

From pleasant

“flatteries” came

fragrant “spices” -

and the music fits

like a glove, not

only with regard to

the prosody, but

also the content.

A short Rezitativo

secco (no. 6), gives

the word to three

other characters:

they arrive at the

tomb, and see the

stone moved aside

from the open

entrance; Mary

Magdalene tells how,

with Mary Jacobi,

they met an angel

earlier, who

announced to them

the resurrection of

Jesus. Peter and

John go into the

tomb, as the Gospel

tells us; now Peter

sees “mit Vergnügen

das Schweißtuch

abgewickelt liegen”

(with pleasure that

the veil lies

unwound). Again it

is noticeable that

the poet quotes here

the longest-held

tradition of the

Christian community;

only because of that

he can say that

Peter finds the veil

“with pleasure” ...

the whole thing is

like an ‘epilogue’

to the universally

known events of

Easter.

There follows Peter’s

Aria (no. 7),

for tenor with basso

continuo and the

violins, which are

doubled an octave

higher by two

recorders. The veil

is, in Peter’s

lines, the symbol

for the sorrow and

crucifixion of

Jesus: “durch dieses

Schweißtuch wird

mein Todeskummer nur

ein sanfter

Schlummer sein”

(through this veil

the grief of my

death is only a

gentle slumber).

Peter teaches us

here, clearly, that,

thanks to the death

of Jesus, the

believer does not

really die when he

dies, but is only

‘temporarily’

separated from life,

thus ‘slumbers’,

until he also rises

up at the Last Day.

In the B-part of the

Aria the cloth is

really seen as a

cloth, which

refreshes and wipes

away the tears from

the cheeks.

It is also

noticeable here, how

well both versions

fit the same music.

In the Pastorale it

is sung to the

sheep; they must, as

the Goddess Flora

calls for, “rock

themselves to sleep”

during the absence

of the shepherds.

Admittedly the

discrepancy between

the content of the

two subjects is

almost unbearable

for us – yet the

music in both cases

is the perfect

bearer of the

meaning; it takes

the event to a

higher (or must we

say a ‘deeper’)

level... This Aria,

through its

instrumentation and

its motif invention,

comes very close to

the tradition of the

“Sommeils”

(sleep-arias) in

French opera, but

seldom was the right

tone so grippingly

found to place us in

a kind of

dream-state. The

bass proceeds almost

throughout in

regular quavers, in

repeated notes or

small intervals. The

upper voices are

dominated by a

gentle rocking

figure in

semiquavers

frequently repeated.

The tenor soloist

inserts himself into

this web in a

lyrical undramatic

way. Throughout its

length the Aria

gives the impression

of almost timeless

slumbers...

The Recitative

(no. 8)

follows, first a

tempo, then arioso

for the two Marys

(soprano and alto)

and basso continuo.

They long “with

burning desire” for

the hour in which

they can see the

Saviour for

themselves. For the

most part both sing

their sighing

Lamento

homophonically, in

which it stands out

how skilfully

expressive is the

way Bach always sets

the repeated cry of

“Ach!” with a

painful tritone

interval between the

two voices. In the Arioso

section a pure trio

comes from the duet;

the basso continuo

imitates the soprano

and alto with the

same motif material.

The Aria (no. 9)

for alto (Mary

Magdalene), oboe

d’amore and strings

is a piece which

moves serenely:

“Saget mir

geschwinde, wo ich

Jesum finde, welchen

meine Seele liebt”

(Tell me quickly,

where I may find

Jesus, whom my soul

loves). In the

Pastorale it is:

“Komm doch, Flora,

komm geschwinde /

Hauche mit dem

Westenwinde / Unsre

Felder lieblich an”

(Come now Flora,

come quickly /

Breathe with the

West Wind / sweetly

on our fields). The

sense of urgency in

the speaker’s plea

is the same in both

cases, the figures

written for the West

Wind illustrate in

the sacred version

rather the

“quickly”. Thus the

community is here

called upon to look

for Jesus in life.

In the Recitativo

secco (no. 10)

the bass closes the

action: “Wir sind

erfreut, dass Jesus

wieder lebt, etc.”

(We are joyful that

Jesus lives again,

etc.) - the faithful

must now celebrate

together the

resurrection of

Jesus.

This is precisely

what happens in the

Closing Chorus

(no. 11): this

magnificent tutti is

in two parts, of

which the first

ressembles closely

the Sanctus (from

1724, BWV 232, III),

which we find later

in the so-called

B-minor Mass: “Preis

und Dank, Herr,

bleiben dein

Lobgesang…” (Praise

and thanks, Lord,

remain thy hymn of

praise…). Running

quaver triplets,

like the clearly

homophonically

scanned “Preis und

Dank“, characterise

this fragment. The

second part, in 3/8

time, (“Eröffnet,

ihr Himmel, die

prächtigen Bogen /

der Löwe von Juda

kömmt siegend

gezogen” – Open up,

O heavens, the

splendid arches, the

victorious Lion of

Judah draws near) is

a powerful fugato,

which recalls for us

the festive D-major

atmosphere of the

opening Sinfonia.

“Bleib bei uns,

denn es will Abend

werden”, BWV 6

(Abide with us,

for it is toward

evening) (Easter

Monday, 1725)

This Cantata was

performed on the day

after the Easter

Oratorio, the 2nd

April 1725. The

Leipzigers were

really spoilt...

The text is by an

unknown poet. The

main theme is taken

from the Gospel

reading: the

well-known episode

of the journey to

Emmaus (St. Luke 24,

13-29).

Three days after his

death, two disciples

of Jesus were on

their way to a

village called

Emmaus, and they

talked of the

crucifixion of their

Master, when

suddenly a stranger

appeared, who went

with them. They did

not know it was

Jesus, who asked

them ‘What manner of

communications are

these that ye have

one with another?’

They were amazed at

the unawareness of

the stranger, and

told him what had

come to pass in

Jerusalem, how the

chief priests and

the rulers delivered

Jesus to be

crucified, how their

hope for Israel was

destroyed by this,

and how also the

sepulchre was later

found empty by the

women and Jesus

himself was not to

be seen. Then Jesus

said unto them “O

fools, and slow of

heart to believe all

that the prophets

have spoken”, and,

beginning at Moses

and all the

prophets, he

expounded unto them

in all the

scriptures the

things concerning

himself. And they

drew nigh unto the

village, whither

they went: and he

made as though he

would have gone

further. But they

restrained him,

saying, “Abide with

us, for it is toward

evening, and the day

is far spent”. And

he went in to tarry

with them. And it

came to pass, as he

sat at meal with

them, he took bread,

and blessed it, and

brake, and gave to

them. And their eyes

were opened, and

they knew him. They

returned to

Jerusalem, and found

the Apostles

gathered together,

and those that were

with them, saying

the Lord is risen

indeed - and they

told what things

were done in the

way.

This fragment, at

the end of the St.

Luke Gospel, has

been interpreted in

every age throughout

Christendom in

countless

commentaries – which

every reader or

listener feels

affects him in his

own way; here it is

about the deepest

recognition of God’s presence.

The Opening

Chorus (no. 1)

is one of the most

beautiful that Bach

has left us in his

Cantatas. The text

from St. Luke was

illuminated

extremely carefully

by the composer and

from all sides, as

if by a painter, who

had fully immersed

himself in the

subject before he

represented it for

us.

C-minor was already

at the time the

appropriate key for

the depiction of

darker subjects;

actually that is

still also the case

for us today. (Why

certainly remains a

secret of ‘nature’).

So the evening, the

night as a

threatening element,

are of course

depicted in this

key.

Bach has set the

short text section

“Bleib bei uns, denn

es will Abend

werden, und der Tag

hat sich geneiget”

(Abide with us, for

it is toward

evening, and the day

is far spent) in

ABA’-form, in which

the A’ is a

shortened repeat of

the A-part.

The instrumental

introduction of 20

bars has a

pronounced Sarabande

character – that

serious dance, which

with Bach often

carries a profound

content. Two oboes

and an oboe da

caccia, with strings

and basso continuo

puts us in the mood

for the coming text.

The oboes with the

continuo prefigurate

the four-part vocal

ensemble, as it will

appear shortly, and

through this

polyphony Bach has

so to speak

stretched ‘a wire’

across. The violins

and viola in unison

repeat in lightly

pulsing quavers and

held notes the

dominant of the key

(G in C minor, B

flat in the

following E flat

major), describing

the ‘abide’, while

the other

instruments spin

their web. The words

“Bleib bei uns” (as

also in the

‘non-speaking’

picture of the oboe

opening) are set

homophonically, as

if in a strong

united prayer. For

“denn es will Abend

werden” a sinking

figure (the falling

evening!) is played

by the three wind

instruments one

after the other.

With these basic

elements Bach has

built the whole

A-part: the

homophonic Sarabande

entry, the lingering

notes of the

‘bleiben’ and the

sinking motif for

the coming evening.

These elements

alternate in all the

parts, in which the

held notes sung by

the voices are

particularly

effective. The end

of the A-part brings

us to the dominant

key of G minor; here

the time changes

from ¾ to a level ¢,

thus from tertiary

to binary. The

Sarabande character

is now replaced by a

non-dancing,

abstract rhythm.

Here comes a denser

and quite nervous

section, which

expresses well the

distress of the

disciples. This is

rather an

apprehensive prayer,

not to have to go

throught the night

alone, and to invite

the mysterious

stranger, whom they

had come to trust,

to stay with them.

Here also Bach

weaves the long

notes of the

‘bleiben’ through

the whole. We find

it with singers and

instruments doubled

and sometimes

independently

instrumental. In the

last four bars of

this turbulent

B-part we suddenly

hear the four

singers examine the

text homophonically

more clearly than

ever: “Und der Tag

hat sich geneiget,

bleib bei uns, bleib

bei uns!” (and the

day is far spent,

stay with us, stay

with us). There

follows, this time

without instrumental

introduction, a

shortened and

intense version of

the A-part, and this

completes the circle

of this wonderful

composition.

After this follows

an Aria (no. 2)

for alto, with an

obbligato solo part

for oboe da caccia

or viola (as in a

later repeat

performance; we have

opted for the viola

here). “Hochgelobter

Gottessohn/Lass es

dir nicht sein

entgegen/Dass wir

itzt vor deinem

Thron/Eine Bitte

niederlegen//Bleibe

unser Licht/Weil die

Finsternis anbricht”

(Highly praised Son

of God/ let it not

be against Thee/

that we now before

Thy throne/ set down

a prayer//Remain,

Ah! Remain our

light/ because the

darkness

approaches). This

text follows

cleverly the lines

of St. Luke of the

opening chorus. Bach

creates as leitmotif

(perhaps the prayer)

a short rising

figure (the viola,

right at the

beginning, later

taken by the alto).

Alto and viola carry

on a dialogue, which

the string bass

supports with a

regular pizzicato.

Twice the alto

clearly illustrates

the word

“Finsternis”: the

line bends over dark

and rarely occurring

minor notes (F flat

and C flat).

The following Chorale

Arrangement (no.

3) is based on

two hymn verses

written by different

poets (Ph.

Melanchthon, 1579,

and Nik. Seltzner,

1611). The soprano

sings the melody

“Herr, bleib bei

uns, etc.” with long

notes, while the

piccolo violoncello

unfolds a highly

imaginative,

continuous solo part

(the welcome

presence of the

Lord?). This piece

clearly illustrates

that for Bach the

piccolo violoncello

was undoubtedly a

‘da spalla’, that is

shoulder,

instrument. The solo

part of the piccolo

violoncello was

written in the score

of the first violin

(and this is not an

isolated case!) –

incidentally in

Bach’s surroundings

the violoncello was

still described as

an “instrument

played on the arm”.

In the Recitativo

secco for bass

and basso continuo (no.

4) the poet

reflects on the

cause of the

suffering and

darkness in human

life. Neither the

‘great’ nor the

‘low’ act according

to Christian

brotherly love, and

(so he concludes)

“darum auch hat Gott

den Leuchter

umgestoßen” (that is

why God has knocked

over the

candlestick). This

very suggestive

phrase from

Revelations connects

wonderfully with the

main theme of the

Cantata: the

longed-for presence

of God among us, so

that he allows his

light to shine on

us.

Now there comes an Aria

for tenor (no. 5)

with strings and

basso continuo,

“Jesu, lass uns auf

dich sehen” (Jesus

let us gaze on

Thee). The word of

Jesus as the light

of the world is

compared here to the

(overturned)

candlestick. The

opening motif of the

violins can perhaps

be taken as a

description of the

unstable

candlestick. When

afterwards there are

rapid running

triplets and other

figures for the

first violins, this

certainly refers to

the sparkling light

(the tenor solo

confirms this with a

long triplet

vocalise on

‘scheinen’). A

further important

element in this

composition is the

clearly scanned

descending triad,

which occurs

repeatedly from the

beginning in the

middle voices,

remains very present

during the piece and

later is isolated in

the tenor solo, and

is pointedly

combined with the

text “Dass wir

nicht” and also

“Lass das Licht”.

The Cantata closes

simply (no. 6)

with a verse from a

Lutheran Hymn

from 1542: “Beweis

dein Macht, Herr

Jesu Christ / Der du

Herr aller Herren

bist etc.” (Prove

thy power, Lord

Jesus Christ/ who

art the Lord of all

lords).

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|