|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25312 - (p) 2009

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25312 - (p) 2009 - rectus

|

|

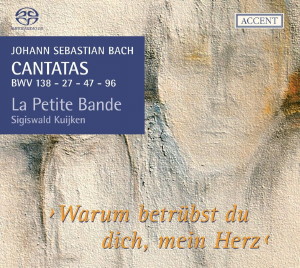

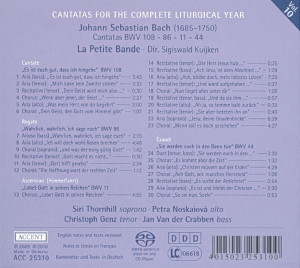

CANTATAS -

Volume 12

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

"Wer weiß, wie

nahe mir mein Ende", BWV 67

|

|

14' 43" |

|

| -

Choral: Wer weiß, wie nahe mir

mein Ende |

4' 23" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Mein

Leben hat kein ander Ziel |

0' 48" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Willkommen! will

ich sagen |

4' 30" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Ach,

wer doch schon im Himmel wär! |

0'

42"

|

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Gute Nacht, du

Welgetümmel! |

3' 12" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Welt, ade! Ich bin dein müde |

1' 08" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Wer

sich selbst erhöhet, der soll

erniedriget werden", BWV 47 |

|

20' 06" |

|

| -

Chorus: Wer sich selbst

erhöhet, der soll erniedriget werden |

5' 18" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Wer ein

wahrer Christ will heißen |

8' 21" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Der Mensch

ist Kot, Staub, Asche und Erde |

1' 32" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Jesu, beuge doch

mein Herze |

4' 07" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Der zeitlichen Ehrn will ich gern

entbehrn |

0' 48" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Warum betrübst

du dich, mein Herz", BWV 138 |

|

16' 41" |

|

| -

Choral & Recitative (alto):

Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz |

4' 44" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass, soprano,

alto) & Choral: Ich bin

veracht |

3' 23" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Ach

süßer Trost |

0' 55" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Auf Gott steht

meine Zuversicht |

5' 05" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ei, nun!

So will ich auch recht sanfte ruhn |

0' 26" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Weil du mein Gott und

Vater bist |

2' 08" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Herr Christ,

der einge Gottessohn", BWV 96 |

|

18' 22" |

|

| -

Choral: Herr Christ, der

einge Gottessohn |

5' 13" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): O

Wunderkraft der Liebe |

1' 18" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Ach, ziehe die

Seele mit Seilen der Liebe |

7' 12" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Ach,

führe mich, o Gott |

0' 48" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Bald zur

Rechten, bald zur Linken |

2' 51" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ertöt uns durch dein

Güte |

1' 00" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Makoto Akatsu, violin

II

|

|

|

- Ann Cnop, violin

II

|

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Bart Coen, flauto

piccolo |

|

|

- Frank Theuns, traverso |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe / oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Vianciane

Baudhuin, oboe / oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Jean François

Madeuf, trumpet (12), Corno (67)

|

|

|

- Oliver Picon, horn |

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Academiezaal,

Sint-Truiden (Belgium) - 21/22

September 2009 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25312 - (1 CD) - durata 69'

52" - (p) 2009 (c) 2011 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

From

the Cantatas, which

J. S. Bach, as

Thomaskantor, wrote

in Leipzig for the

15th to the 18th

Sundays after

Trinity, we have

chosen for our cycle

(which is to include

one Cantata for each

Sunday), the

following:

- BWV 138 “Warum

betrübst du dich,

mein Herz?” (5th

September 1723 –

15th Sunday after

Trinity)

- BWV 27 “Wer weiß,

wie nahe mir mein

Ende?” (6th October

1726 – 16th Sunday

after Trinity)

- BWV 47 “Wer sich

selbst erhöhet, der

soll erniedriget

werden” (13th

October 1726 – 17th

Sunday after

Trinity)

- BWV 96 “Herr

Christ, der einge

Gottessohn” (8th

October 1724 – 18th

Sunday after

Trinity)

Cantatas BWV 27 and

BWV 47 both date

from the same year,

1726, and were also

performed for the

first time on

consecutive Sundays.

Note: On

musical grounds we

have departed from

the chronological

sequence on this CD,

and start with BWV

27, followed by BWV

47, BWV 138 and

finally BWV 96.

“Warum betrübst

du dich, mein

Herz?” - BWV 138

On the 5th September

1723 (the 15th

Sunday after

Trinity) Bach was

still in the first

year of his

appointment in

Leipzig. He first

started there after

Trinity Sunday (the

Sunday after

Whitsun). The

Cantatas composed

during this initial

time in Leipzig were

the fruit of a

creative spirit

extraordinarily

‘deep mined’, as we

will also see here.

The unknown poet of

this Cantata had

fallen back on an

old church hymn from

Nuremberg (1561),

which is sometimes

attributed to Hans

Sachs (without any

real basis). He only

used the first three

verses of this

14-verse hymn, and

in fact verbatim (in

movements 1-2-6

according to the

Neue Bach-Ausgabe;

A. Dürr, in his

Cantatas of J. S.

Bach, divides the

NBA no. 2 into two

numbers, and thereby

has seven numbers

altogether, against

six in the NBA. We

adhere to the NBA

numbering). All the

verses of this

church hymn have

five lines.

The three verses of

the old church hymn

used intend to

summon the faithful

to a deeper trust in

God. The later

Baroque poet, who

laid out this

Cantata, each time

‘answers’ this call

in his contribution

to the text. At

first with a real

complaint about his

currently wretched

situation; but as of

the third movement

he concerns himself

with his trust in

God. The libretto of

this Cantata,

therefore, holds up

a mirror to the

faithful, and urges

them, despite

difficulties and

distress, to rely

only on God. This

connects with the

Gospel reading for

this Sunday (St.

Matthew 6, 24-34):

the exhortation not

to live with little

faith and timidly,

but to trust that

God in his goodness

holds our life in

his hand, comes from

the Sermon on the

Mount.

In the verse of the

Baroque poet we find

clear allusions to

this Gospel reading.

In both the first

movements Bach kept

strictly to the

structure of the

libretto. The old

hymn text is

fundamentally set

polyphonically and

assigned to the

vocal quartet, the

new poem presented

alternately by the

individual soloists

in recitative style

(accompagnato and

also sometimes

secco).

In the process, in No.

1 each of the

three opening lines

is first announced

by the tenor, before

it is sung by the

full vocal quartet.

Before this tenor

announcement there

is each time an

instrumental

introduction for

every line, in which

the strings play the

tenor motif. In

contrast we hear

completely different

material from the

oboes. The first

oboe presents the

old chorale melody

of the respective

lines, and the

second plays with it

a chromatic

descending sighing

motif. When,

finally, the

four-part version of

the line begins, the

soprano sings the

old chorale melody

already played by

the first oboe, and

the bass, reinforced

by the continuo,

brings in the

sighing motif of the

second oboe as a

lamento.

Bach’s treatment of

these three opening

lines is a

marvellous, striking

example of his

constructive

invention, in which

nothing is left to

chance or to a

so-called moment of

inspiration, but

rather everything is

carefully weighed

and realised in the

best way possible.

This is emphasised

time and again. So,

for example, the

main motif, which is

first presented by

the first violins

and interprets the

words “Warum

betrübst du dich,

mein Herz”, is

extended as a

connecting thread

through the whole

structure; it is

taken up in the

following entries in

succession about

3x12 times.

The compact

structure of the

first three lines is

now followed by the

above mentioned

commentary of the

poet, set by Bach as

an recitativo

accompagnato for the

alto “Ach, ich bin

Arm, mich drücken

schwere Sorgen”.

With long-held notes

the strings will

present the

emotional lament

(Lamento) of the

poet with a

chromatic descending

basso continuo in

regular tempo. At

the same time the

two oboes repeat a

motif, which

illustrates very

well the “heavy

cares”. This

particular motif

then serves in the

vocal bass as a

crossover to the

four-part setting of

the last two lines,

which are sung

simply (“Vertrau du

deinem Herren

Gott/Der alle Ding

erschaffen hat”).

Next No. 2

brings us the second

verse of the

original hymn,

likewise enriched in

a new poem by the

Baroque poet.

Noteworthy here is

the poetic structure

(which incidentally

Bach in turn follows

down to the last

detail), where, in

the first verse,

each of the three

old lines poses a

question, which the

poet ‘answers’, but

we find the process

reversed in this

instance; now the

Baroque poet asks

three sorrowful

questions, to which

the answers had

already been given

in the lines of the

original hymn. This

antithetical

symmetry is a

typical and much

favoured Baroque

figure.

The bass begins with

a dark lamentation

(“Ich bin veracht”,

which dies away with

the question “Wie

kann ich nun mein

Amt mit Ruh

verwalten / Wenn

Seufzer meine Speise

und Tränen das

Getränke sein?”. The

answer in the old

text (set in four

parts as before) is

positive: “Er kann

und will dich lassen

nicht / Er weiss gar

wohl was dir

gebricht” etc. Bach

sets the hymn text

(so the first three

lines of the second

verse) strictly

homophonically, so

that it is easy to

understand – each

time the oboes play

a short lively

figure between the

three lines (here

again as an

antithesis to the

accompagnato of the

alto in No. 1, where

they illustrated the

“heavy cares”). The

soprano steps in

here with an

accompagnato with

strings. Her lament

concludes with the

questioning cry “Ist

jemand, der sich zu

meiner Rettung

findt?”. The answer

is given by the last

two lines of the old

verse: “Dein Vater

und dein Herre Gott,

etc”. This original

text is again set by

Bach for four

voices, but this

time in an imitative

way: the tenor, bass

and alto sing the

text in a fugato.

The soprano takes

the simple old hymn

simultaneously with

the alto: one must

conclude that these

repeated statements

in the text will

give rise to the

repeated help of God

as well. Now the

last lamenting lines

of the poet fall to

the alto (in a

recitativo secco),

which end once again

with a plea: “Ach!

Armut, hartes Wort,

wer steht mir denn

in meinem Kummer

bei?”. A comforting

answer follows again

in the two lines of

the hymn “Dein Vater

und dein Herre Gott,

etc”, in which Bach,

mind you, modifies

the sequence of the

fugato entries.

Thus in a very

elaborate way are

the first two verses

of the 1561 hymn

presented to us.

After the comforting

thoughts of the last

lines, which we have

just heard, the poet

regained his

confidence, and

changed from his

lament to words full

of hope. In the Secco

for tenor (No. 3)

a positive composure

clearly shines

through: God helps

me – if not today,

then tomorrow...

This recitativo

secco leads

seamlessly into the

Aria (No. 4)

for bass and

strings. Here the

regained confidence

has completely

penetrated the mind

of the poet. Bach’s

music again totally

reflects this happy

state of mind. It

sounds like a kind

of stylised

‘Polonaise’, in

which, above all,

the first violins,

the bass soloist and

the basso continuo

frequently imitate

each other (to a

lesser extent the

middle voices also

participate). Both

the ‘stationary’

chief motif and the

more rapid figures

jump in a varied way

from one part to

another. Noteworthy

are the long

vocalises, which

each time must

indicate the

permanence; on

‘walten’ (“mein

Glaube lässt ihn

walten”), and on

‘nagen’ and ‘plagen’

(“Nun kann mich

keine Sorge nagen,

nun kann mich auch

kein Armut plagen”,

as it is put in the

text). Also the

words ‘Freude’ (joy)

and ‘erhalten’

(provide), (both in

the B-part of the

aria), are ‘painted’

by the composer as

matching

rhetorically;

‘Freude’ through a

threefold rising

motif (matched by

the first violin),

and ‘erhalten’ with

two long-held notes.

After this catharsis

the alto (Recitativo

secco, No. 5)

proclaims in a short

summary, how we can

bid farewell to our

cares, and further

“wie im Himmel

leben” ...

Then follows the Closing

Chorale (No. 6),

(the third verse of

the old church hymn

of 1561). That

invitation “to live

as if in heaven” was

not left ‘unused’ by

Bach. This hymn

verse is presented

by the singers in a

simple homophonic

four parts, and

meanwhile the

instruments enjoy

themselves in a

festively figured

movement, in minuet

tempo; the picture

of heavenly joy...

“Wer weiß, wie

nahe mir mein

Ende”, BWV 27

(for the 16th

Sunday after

Trinity, the 6th

October 1726)

This is the last of

four Cantatas, which

Bach wrote for this

Sunday (the first in

Weimar in 1713, the

other two in Leipzig

in 1723 and 1724).

The theme of the

Gospel reading (St.

Luke 7, 11-17) is

the raising from the

dead of the young

man from the city of

Nain. The unknown

text poet has here

used this theme only

as an opportunity to

articulate his own

thoughts about life

and death – above

all it is about him

and a good end to

his own life. He

longs to be received

afterwards into the

peace of God, and

therefore directs

all his actions

toward this moment.

He will be ready for

it at any time.

“Mein Leben hat kein

ander Ziel / Als

dass ich möge selig

sterben / Und meines

Glaubens Anteil

erben” he says in

the Recitativo (no.

2). From this

perspective, the

poet welcomes death,

asks for it and bids

the world adieu.

Such thoughts are

far from us today,

in a time when we

often view death

thanklessly as an

‘enemy’, yet they

were commonplace in

the Lutheran climate

of Bach’s time. In

my opinion Bach

alone is able to

touch on this

profound central

point like no other,

in which life and

death meet in a

mystical unity.

In the Opening

Movement (No. 1)

of the Cantata the

poet uses an old

chorale verse (the

first verse of the

hymn “Wer weiss, wie

nahe mir mein Ende”

by Ämilie Juliana

von

Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt,

from 1686). As was

the case with the

Cantata BWV 138, the

poet here inserts

his own lines

between the six old

chorale lines of

this verse, and thus

fashions a very

meaningful dialogue

with the old text.

As usual, Bach sets

the old text for

four voices and the

new text as

recitative for the

various singers. The

movement starts with

a short instrumental

introduction for two

oboes, the strings

and the basso

continuo – twelve

bars, of which the

first six have a

pedal note on C.

These bars form one

of the most

beautiful examples

of the ‘correct’ use

of the dark

character of the key

of C minor. The

basso continuo sets

the calm 3/4 time

signature, the

remaining strings

play a repeated and

hesitant phrase with

descending quavers.

Over this structure,

the two oboes, one

after the other in

imitation, play a

lyrically plaintive

motif. Where the

sinking quaver

phrases of the upper

strings are heard,

the basso continuo

undertakes the

mirror image of the

same figure, rising

instead of

descending.

Undoubtedly the two

versions of the same

quaver motif

represent the death

(laying in the

tomb?) and the

prayer (the rising

phrase).

Incidentally, after

two bars of the

rising phrase the

violins also join in

with a rising figure

(this time in

semiquavers). When

finally in the

thirteenth bar the

vocal ensemble

enters with the

first line of the

hymn “Wer weiß,

wie nahe mir mein

Ende” (a corno

da tirarsi doubles

the chorale melody),

the descending

figures appear again

in the upper

strings. After this

first chorale line

the soprano emerges

(under the

continuing string

figures and oboe

dialogue). In a

measured recitative

she gives the poet’s

answer to the first

line of the hymn:

“Das weiß der liebe

Gott allein” etc.

From here on the

movement develops as

mentioned above.

Chorale lines and

the poet’s new lines

alternate (in

recitative by the

alto and afterwards

by the tenor, but

still sung a tempo),

until the end of the

verse. Finally, as

an epilogue, the

instrumental

introduction is

repeated.

This wonderful

architecture is

followed by a simple

Recitativo for

tenor (No. 2),

which expresses the

main thoughts of the

poet: “Mein Leben

hat kein ander Ziel,

als dass ich möge

selig sterben”, and

again “Ende gut

macht alles gut!”.

A highly unusual

instrumentation in

the Aria for

alto, oboe da

caccia and

obbligato organ

with string bass

(No. 3) makes

these thoughts

clear. The first two

lines of this aria

have been borrowed

by the poet from the

cantata text by

Erdmann Neumeister

(1700): “Willkommen

will ich sagen /

Wenn der Tot ans

Bette tritt”. In the

B-part the aria

further states:

“alle meine Plage

nehm ich mit”, which

gives the composer

the opportunity for

an expressive

chromaticism. Why

did Bach choose such

a strange

instrumentation for

this piece? I

venture to give an

answer: could not

the organ be a

symbol of heavenly

music here, and the

‘oboe da caccia’ an

instrument blown by

an angel? The poet

here is yearning for

the next world. The

introduction to this

Aria (before the

singer enters) is

very detailed, and

contains the whole

compositional

material of the

piece.

In the following Recitativo

accompagnato for

soprano and

strings (No. 4)

the poet once again

expressed his

yearning and

impatience for the

mystical union with

the Lamb of God.

With the twice

repeated cry “Flügel

her!” (yes, the

impatience comes

through thus far!)

the violins are

heard in two rapid

rising scale

passages. A more

naïve or simpler

description cannot

be imagined – here

Bach is very simple,

and it works

wonderfully.

The bass follows

with his Aria

(No. 5) with

strings “Gute

Nacht, du

Weltgetümmel”; the

piece initially

displays a kind of

dance-like dignity

(Polonaise, slow

Minuet?), for the

words “Gute Nacht”,

but soon comes the

expected description

of ‘tumult’ with

rapid, violent

semiquaver figures.

The whole Aria comes

alive with the

confrontation of

these two

contrasting

features, and ends

with “gute Nacht”...

In the Closing

Chorale (No. 6)

(1646, J. G.

Albinus) “Welt, Ade!

Etc.” (World,

farewell!) just this

once Bach inserts an

existing multi-voice

setting of the

chorale melody, and

in fact uses a

five-part

harmonisation by

Johann Rosenmüller

from 1652. The basis

for this curious

fact is lost for

ever, yet this more

archaic movement

certainly fits in

here perfectly. In

addition, this

indirectly gives us

interesting

information about

the vocal setting.

The second soprano

in Rosenmüller’s

five-voice setting

is only found in the

instrumental

doubling, that is,

it was not sung. If

now Bach actually

had a choir of about

sixteen singers for

his Cantata

performances and had

not used a solo

vocal quartet, he

would certainly not

have had to leave

out the second

soprano ...

“Wer sich selbst

erhöhet, der soll

erniedriget

werden”,

BWV 47

This Cantata is the

third of the three

which Bach wrote for

this 17th Sunday

after Trinity; it

was first performed

on the 13th October

1726 – thus a week

after the Cantata 27

mentioned above.

We know the text

poet of this

Cantata: Johann

Friedrich Helbig

(1680-1722), the

Council Secretary

for Eisenach at the

time that G. Ph,

Telemann was the

court Kapellmeister.

Helbig wrote a

complete year’s

cycle in 1720, and

Telemann set almost

all of them.

BWV 47 is the only

Cantata that Bach

composed to a text

by Helbig. He had

possibly taken it

from Telemann’s

compostion, or from

Helbig’s printed

year’s cycle. The

main thought is

presented as a

‘motto’ in the

opening movement of

the Cantata. It is

the end of the

Gospel lesson for

the relevant Sunday

(St. Luke, 14, 11):

“Wer sich selbst

erhöhet, etc.”. The

poet develops in the

next two movements

his ‘sermon’ about

the arrogance of

mankind, which is in

complete contrast to

the humility of

Christ. There

follows a moment of

prayer (Aria No. 4)

“Jesu, beuge doch

mein Herze, etc.”,

and it closes with a

chorale verse, that

is with the eleventh

church hymn “Warum

betrübst du dich”

(Nuremburg 1561)

from Cantata BWV

138.

Bach has poured the

prose text of St.

Luke (“Wer sich

selbst erhöhet,

etc.”) into a

monumental Tutti

movement (No. 1).

The two oboes,

strings, four vocal

parts and basso

continuo form a web

which is most

cleverly structured

and has great

variety and inner

regularity. It

begins with a long

instrumental

introduction of 44

bars, in which all

the material is

reviewed.

At first one

believes that an

instrumental

concerto is being

heard. The attentive

listener, however,

will soon recognise,

in the first four

bars, the idea of

the ‘high-low’

confrontation

(‘raise up’ against

‘abase’). Disjointed

individual phrases

alternate in

different registers,

until in the fifth

bar a more

horizontal quaver

figure emerges,

which serves as an

advance notice of

the later fugue

subject for the

voices. In a purely

‘concertante’ style

Bach develops the

introduction further

using these two main

constituents

(disjointed figures

and horizontal lines

of quavers), until

finally the vocal

fugue enters in the

tenor, over an exact

repetition of the

opening bars of the

introduction.

Bach designed the

fugue subject and

its related

counter-subject

completely within

the limits of the

text, both of them

are, so to speak,

grown from the text.

The first half of

the text (“Wer sich

selbst erhöhet, der

soll erniedriget

werden”) forms the

actual subject in

two times four and a

half bars, and the

second half of the

text (“und wer sich

selbst erniedriget,

der soll erhöhet

werden” forms the

counter-subject of

the same length. The

main idea of St.

Luke’s text, ‘high’

and ‘low’, is used

here pointedly,

carefully and

musically by Bach,

so that the whole

phrase of St. Luke

is set, so to speak,

as a painting in

music. In the actual

theme, the first

half of the text

therefore, the

musical line rises

for “Wer sich selbst

erhöhet” and

descends for “der

soll erniedriget

werden”. The

counter-subject, the

second half of the

text, starts with

“und wer sich selbst

erniedriget” at the

top, so that it can

run downwards and go

upwards again with

“der soll erhöhet

werden”. So after

the introduction of

the subject (in the

tenor), the

following entries of

the subject (first

in the alto, then in

the soprano and

finally in the bass)

are time and again

confronted by the

counter-subject

running in

contramotion. It

results, therefore,

in a thick web of

completely ‘regular’

complemantary

voices. Even the

non-thematic ‘full

voices’, which

appear next to the

subject and

counter-subject,

‘obey’ the text idea

in their musical

portrayal.

Like the first tenor

entry, the following

fugue figures are

always accompanied

by the opening

instrumental bars as

well, with the

disjointed figures

for ‘higher’ and

‘lower’. After the

first four bars of

the last entry, sung

by the bass to “Wer

sich selbst

erhöhet”, the

strings double the

remaining vocal

group. Four bars

later there even

comes, at the

culmination of the

fugal episodes, the

entry of a fifth

subject, which is

entirely unexpected.

The two oboes play

the subject in

unison over the four

voices, and actually

now in B major

instead of the G

minor at the start

of the fugue. After

this a new passage

starts, in which the

basso continuo plays

the runnng quaver

figures of the fugue

subject one after

the other for almost

25 bars. In between,

the short, broken

figures of the

instruments

alternate with

equally short vocal

sections, which

carry the fugue

subject in the bass

(with the dominant

basso continuo) and,

in the

‘complementary

voices’, a

three-part ‘stretto’

of the slightly

modified fugue

subject. This always

takes place with the

opening text “Wer

sich selbst

erhöhet”. This

alternating passage

is repeated twice,

and in fact the key

rises in turn as is

appropriate for the

text. After this we

have again arrived

at G minor, and the

whole fugue, which

had started in bar

45, is repeated, but

with some remarkable

variations. So now

the soprano starts,

and the next entries

occur simply in a

downward sequence

for alto, tenor and

bass (yet again the

picture of

abasement).

From the alto entry

the instruments

(strings and oboes)

now also run

together, doubling

the voices colla

parte, until the

oboes distance

themselves in order

to play in turn

their fifth entry in

the full polyphony.

After this, with the

arrival of E flat

major, Bach brings

in again the

concentrated passage

of short alternating

sections and the

‘stretto’ in rising

keys (to the opening

text). Here,

however, with the

second, higher

‘stretto’ insertion

(and without

instrumental

interruptions) is

added a third fugal

episode. The

tenor (main subject)

and the alto

(counter-subject)

are doubled by the

viola and second

violin with the

assistance of the

two independent

oboes. When

afterwards the bass

(with the main

subject) and the

soprano come in, all

the instruments,

colla parte with the

voices, join in an

eleven-bar

transition. This

leads to a ‘hidden’

da capo of the

instrumental

introduction (bars 1

to 45)! I say

‘hidden’, because

the polyphonic vocal

web, which still

continues at this

moment, diverts our

attention from the

da capo entry of the

instruments. Two

bars later, however,

the singers for

their part finally

join the instruments

in a festive tutti.

The instruments play

their introduction

verbatim to the end,

the vocal quartet

sings over them with

all the known

material; a new

creation which leans

towards the

instruments, but in

part proceeds

independently.

With this

combination, this

large-scale choral

work of 228 bars

comes to an end. One

can only marvel at

such a piece, and be

astonished with what

mastery Bach plays

with the rules,

which he imposes on

himself. Freedom

within order, it

allows us to dream!

As Movement No.

2 of the

Cantata there

follows an Aria

for soprano,

obbligato violin

and basso continuo.

“Wer ein wahrer

Christ will heißen /

Muss der Demut

sich befleißen; /

Demut stammt aus

Jesu Reich”. So the

poet begins his

‘sermon’ in the

A-part of the text.

The violin part,

which probably was

originally intended

for obbligato organ,

surely portrays in

repeated rapid

figures the

enthusiasm necessary

for man to proceed

toward humility, in

which the soprano

sings the text with

a pleasantly lyical

and soft line. This

A-part is

long-spun-out, and

makes one

continuously aware

of the chief

message. In the

B-part the tone

changes completely:

“Hoffart ist dem

Teufel gleich / Gott

pflegt alle die zu

hassen / So den

Stolz nicht fahren

lassen”. To arrive

here Bach turns

everything

upside-down. The

opening motif of the

violins is now

played in the

instrumental bass.

‘Arrogance‘ it is

with which the

servant (the bass

accompaniment)

undertakes the chief

rôle! ... And it

does not stop there:

the basso continuo

goes further with a

continuous

domineering staccato

figure! In the

soprano the word

“Hoffart” is now

proudly heard on a

long-held note,

which, after a set

phrase, turns into a

nervous short trill,

which also comes

back in the next two

bars metrically

accented. On

“hassen” Bach writes

two staccato dots,

in order to

emphasize the word;

these two scanned

accents also form

the kernel of the

ostinato rhythmic

figure in the violin

part, which

throughout this

B-part is written

for two voices. This

rather

un-violin-like

writing is perhaps

also indicative of a

previous organ part.

Shortly before the

end of the B-part,

the soprano is

allowed a virtuoso

passage on “fahren

lassen”: the picture

of the detour, the

long journey away

from pride ... The

whole A-part is then

repeated.

No. 3 is an Recitativo

accompagnato for

bass with the

strings. The text

poet Helbig

moralises further.

Without too much

poetics he portrays

the arrogant, proud

man. He ought to be

ashamed in the face

of Christ, who

really exercises the

greatest humility.

After “Folge Christi

Spur” the strings

play a series of

rising chords. They

culminate in a long

note on the word

“Gott”. Nothing with

Bach is chance...

The bass follows

with an Aria

(No. 4) with

basso continuo and

two obbligato treble

instruments: oboe

and violin. After

his ‘sermon’ the

poet composes a

prayer: “Jesu, beuge

doch mein Herze”.

The piece is a

wonderful example of

four-part

counterpoint for two

high and two low

parts. The thematic

material ‘shows’ the

bending with

multiple ‘bowed’

figures (clearly

represented in the

opening bars of the

violins. One only

follows the line of

sound ‘visually!);

all parts make use

of the same figures,

always alternately.

With “und den

Hochmut ganz

verfluchen” Bach

again writes

staccato dots in the

middle of the

vocalise on

“Hochmut”, and also

a short trill on

“verfluchen”; small

suggestions for a

description full of

affekt! For the

penultimate line,

“Gib mir einen

niedern Sinn”, the

“Gib mir” is

beautifully set with

repeated descending

figures; God ‘gives’

from on high... In

the last line, “dass

ich dir gefällig

bin”, the long

vocalise by the bass

on “gefällig” is

remarkable. At the

same time the

‘bowed’ motifs are

omnipresent in every

part. The

instrumental

introduction is

repeated at the end,

which closes the

aria reverently.

A simple Chorale

(No. 5 – Nuremberg

1561) summarises

this Cantata.

“Herr Christ, der

einge Gottessohn”,

BWV 96

(18th Sunday

after Trinity)

This Cantata was

first performed on

the 8th October 1724

in Leipzig. In 1726

Bach wrote a second

Cantata for this

same Sunday (then

the 20th October):

BWV 169 “Gott soll

allein mein Herze

haben” (God alone

should have my

heart).

This Cantata BWV 96

is a Chorale

Cantata, that is to

say, the whole text

comes from a single

Chorale text; in

this case an old

church hymn of five

verses from 1524, by

Elisabeth

Creutziger. Chorale

Cantatas either used

the whole text

verbatim, or only

the first and last

verses verbatim,

combined with a

‘reworking’ of the

middle verses in a

newer form. BWV 96

belongs to the

latter category; so

here the second and

third original

verses for

Recitativo no. 2 and

Aria no. 3 have been

reworked. The

Recitativo no. 4 and

the Aria no. 5 were

derived from the

fourth verse. No. 6

is thus the fifth

and last verse of

the old hymn. Each

verse of the old

hymn consists of

seven lines. As so

often, the text

reworker also

remains unknown.

The church hymn

contains a

correlation with two

liturgical events:

on the one hand with

Epiphany (6th

January), and on the

other hand with this

18th Sunday after

Trinity. In the

related Gospel

reading (St. Matthew

22, 34-46) there is

the scene in which

Jesus asks the

Pharisees about the

Messiah, and at the

same alludes to the

latter being called

‘Son’ and also

‘Lord’ of David...

The comparison of

Christ with the

morning star is

pointed out in the

first verse (first

movement here

therefore), clearly

from the Epiphany

(6th january); in

the Recitativo secco

(no. 2) reference is

made to the end of

the Sunday lesson,

in which Christ, who

has now appeared, is

already anticipated

by King David, of

whose line he was

born, and by whom he

was honoured as his

Lord. Further on in

this Recitative, as

well as in the

following Aria (no.

3), the emphasis is

placed on the boon,

which the Coming of

Jesus symbolises for

all the faithful.

The Secco no. 4 and

the Aria no. 5 (both

of them derived from

the original fourth

verse) are a

personal plea from

the poet, who

reworked the text:

may Jesus lead him

in the right way. He

must not let him

stray “bald zur

Rechten, bald zur

Linken”, but guide

him straight to

Heaven’s gate. The

Closing Chorale from

1524 implies

verbatim, in early

Baroque contrast,

how Christ our Lord,

the only Son of God,

“must kill the old

mankind” in us, and

awaken us to a “new

life” - so that we

direct “our souls

only to him”.

Musically the Opening

movement (No. 1)

is a highly

calculated

structure, merely

because the old

chorale verse

consists of seven

lines. At the

beginning Bach wrote

vivace; the piece is

in 9/8 time (in

which 9 is three

times three), and

here “Herr Christ,

der einge

Gottessohn!”

certainly embodies

perfection, as it

had already existed

centuries earlier in

mensural notation.

The relationship

with Epiphany and

also thereby with

Christmas is clearly

recognisable in

Bach’s composition.

The piccolo recorder

undoubtedly

describes the

shining morning star

(symbol of the

newborn Jesus child)

with its extremely

high figuration, and

the whole character

of the piece is

unmistakably

pastoral. After an

instrumental

introduction comes

the first line. The

vocal parts are

simply set, in that

the alto sings the

old chorale melody

with long notes

(doubled by a

‘corno’ and the two

oboes), during which

the three others

freely imitate the

opening motif of the

instrumental

introduction (as it

is presented by

the oboe and

the first

violin). The

following

lines are set

in a similar

way, and each

one is

connected to

the previous

one by an

interlude in

the character

of the

introduction.

The music for

both the first

lines is

repeated for

the third and

fourth lines;

then follows

the three last

parts in the

manner

described

above.

For the fifth

line (“Er ist

der

Morgensterne”)

Bach lays out

the harmonic

structure so

that the key

is rapidly

raised by a

tone

(undoubtedly

indicating the

rising morning

star); for

that he must

allow himself

some freedom.

The prevailing

chorale melody

is accordingly

raised by a

semitone,

otherwise this

charming ploy

would not have

been possible.

After the last

line there

follows a

greatly

reduced

version of the

introduction.

The Recitativo

secco (No. 2)

for alto

follows, in

which, first

of all, the

Coming of

Christ is

recalled. On

the words “im

letzten Teil

der Zeit zur

Erde sinket”

the secco

declamation

changes to a

more arioso

kind of

singing, in

which the

voice and

basso continuo

imitate each

other with the

descending

figure, as

expected. The

remaining

lines of this

reworked verse

are again

declaimed in

the secco

style.

The Tenor

Aria (No. 3)

with obligato

transverse

flute and

basso

continuo, a

reworking of

the original

verse of the

old hymn, has

at the

beginning the

verb “ziehe”

as the

“keyword”:

(The text

reads: “ Ach

ziehe die

Seele mit

Seilen der

Liebe”. Bach

meets it

precisely and

simply. Three

adjacent notes

(going up and

also sometimes

going down)

form the

descriptive

figure, which

is regularly

repeated, in

the three

parts. This is

the ‘drawing’,

upwards as in

every

direction, the

hand of Jesus

leading us

...! The text

is set in the

dactylic

sounding

Amfibrachus, a

dynamic

metrical foot

(short/long/short),

which, with

steady

repetition,

has a strong

binary effect

(2/4 or 4/4

time). Bach

uses this

characteristic

feature

deliberately,

does not

avoid the more

certain force given

to the expression,

which was already

perceptible through

the many repetitions

of the text. For

colourful words like

“kräftig” (mighty)

and “entbrennen”

(flare up), Bach

writes longer

figurations for the

voice and

(analogously) in the

flute part. Time and

again the basso

continuo makes a

great effort to

present the figure

of “ziehen”.

No. 4 is a

short Recitativo

secco for soprano,

which leads into Aria

No. 5 (bass and

strings); as

mentioned, both are

from the original

fourth verse

‘reworked’. The

secco limits itself

to communicating the

text, without

particular ploys or

‘descriptive’

elements: “mit

deiner Hilfe, Jesu,

werde ich bestimmt

die Bahn zum Himmel

gehen” – so runs the

sense of this verse.

Instead, however,

the Aria is a true

description of the

text. The “Bald zur

Rechten, bald zur

Linken / Lenkt sich

mein verirrter

Schritt” in the

A-part of the Aria

is a rewarding

opportunity for the

contrasting

portrayal of the

theme, and as such

is used in exemplary

fashion by the

composer. In the

first line of the

B-part (“Gehe doch,

mein Heiland, mit”)

Bach limits himself

to a simple measured

and supporting

illustration of the

‘going’ in the

strings. When it

then goes further,

however, with “Lass

mich in gefahr nicht

sinken” (let me not

sink into danger)

etc., there comes

again into view the

contrasting

portrayal of the

‘right-left’, until

the end of the Aria

(exceptionally, the

A-text is not

repeated, the

strings only repeat

the introduction).

After this very

rhetorical bass Aria

the whole ends with

the simply set Closing

Chorale from

1524 (No. 6

of the Cantata), in

which the basic idea

of the text is once

again summarised.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|