|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25311 - (p) 2009

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25311 - (p) 2009 - rectus

|

|

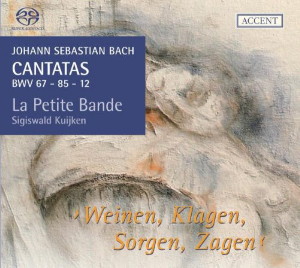

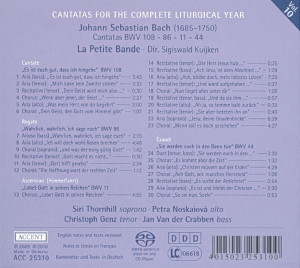

CANTATAS -

Volume 11

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Quasimodogenite |

|

|

|

"Halt im

Gedächtnis Jesum Christ", BWV 67

|

|

12' 57" |

|

| -

Chorus: Halt im Gedächtnis

Jesum Christ |

2' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Mein Jesus ist

erstanden |

2' 35" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Mein Jesu,

heiüest du des Todes Gift |

0'

27"

|

|

|

| -

Choral: Erschienen ist der

herlich Tag |

0' 36" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Doch

scheinet fast |

0' 47" |

|

|

| -

Aria & [Chorus] (bass):

Friede sei mit euch |

4' 43" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Du Friedefürst, Herr Jesu |

0' 54" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Misericordias Domini |

|

|

|

| "Ich

bin ein guter Hirt", BWV 85 |

|

18' 47" |

|

| -

Aria (bass): Ich bin ein

guter Hirt |

3' 09" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Jesus ist ein

guter Hirt |

3' 14" |

|

|

| - Choral (soprano):

Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt |

5' 37" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Wenn die

Mietlinge schlafen |

2' 53" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Seht, was die

Liebe tut |

2' 53" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Ist Gott mein Schutz und treuer

Hirt |

1' 01" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jubilate |

|

|

|

| "Weinen, Klagen,

Sorgen, Zagen", BWV 12 |

|

25' 28" |

|

| -

Sinfonia |

2' 37" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Weinen, Klagen,

Sorgen, Zagen |

8' 07" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Wir

müssen durch viel Trübsal |

0' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Kreuz und Krone

sind verbunden |

6' 25" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Ich folge

Christo nach |

2' 04" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Sei getreu,

alle Pein |

4' 43" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Was Gott tut, das ist

wohlgetan |

0' 52" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I, violoncello piccolo

(da spalla) |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Makoto

Akatsu, violin II

|

|

|

- Ann Cnop, violin

II

|

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Patrick

Beuckels, traverso |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe / oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Vianciane

Baudhuin, oboe / oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Jean François

Madeuf, trumpet (12), Corno (67)

|

|

|

- Yukiko

Murakami, fagotto |

|

|

- Korneel

Bernolet, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Rosario,

Bever (Belgium) - 27/28 April 2009 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25311 - (1 CD) - durata 55'

42" - (p) 2009 (c) 2010 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

This

recording contains

the Cantatas for “Quasimodogeniti”,

“Misericordias

Domini” and “Jubilate”

Sundays; these are

the three Sundays

after Easter.

For Quasimodogeniti

we have two Bach

Cantatas (BWV 67 and

42), and for Misericordias

Domini we have

three (BWV 104, 85

and 112) as we do

for Jubilate

(BWV 12, 103 and

146). All these

pieces bear the

overwhelming mastery

of Bach in

themselves. So our

choice of these

three Cantatas for

the present

recording was made

for no particular

reason.

“Halt im

Gedächnis Jesum

Christ”, BWV

67

(Hold in

remembrance Jesus

Christ) for

Quasimodogeniti

Sunday 16th April

1724.

Although the text of

this Cantata was

printed at the time

(in Texte Zur

Leipziger

Kirchen=Music, auf

die

H.Oster=Feiertage,

Und die beyden

folgenden Sonntage

Quasimodogeniti

und Misericordias

Domini. 1724.

Leipzig, Gedruckt

bey Immanuel

Tietzeni), the

name of the poet

remains unknown;

critical examination

of the style alone

does not permit any

certain conclusion

about the

authorship.

The compiler of the

text, or the poet,

has gathered up his

material from

various sources:

Paul‘s Second Letter

to Timothy (Ch. 2,

8), St. John‘s

Gospel (20, 19) and

old chorale texts by

Nikolaus Hermans

(1560) and Jakob

Ebert (1601). The

Gospel Lesson for Quasimodogeniti

Sunday is St. John

20, Ch. 19-31: Jesus

appears to his

disciples after his

Resurrection.

Thomas, who was not

there, did not

believe his friends

when they told him

about it, and said

that he would only

believe it if he saw

and could touch

Jesus‘s wounds

himself. A week

later Jesus appeared

again to the

apostles and told

Thomas that he

should place his

hand in the wounds,

whereupon Thomas

cried out loudly and

said that Jesus

would be my Lord and

my God. Then Jesus

spoke the famous

sentence “Because

thou hast seen me,

thou hast

believed: blessed

are they that have

not seen, and yet

have believed.”

So belief is – or

rather the difficulty

of believing – the

main theme of this

work, wholly in

accord with the

thoughts in the

Gospel Lesson.

The motto is the

quotation taken from

Paul‘s Second Letter

to Timothy “Halt

im Gedächtnis

Jesum Christ, der

aufgestanden ist

von den Toten“

(Hold in remembrance

Jesus Christ, who is

risen from the

dead). The faithful

are encouraged not

to think and behave

like Thomas. These

words by St. Paul

are sung in the

opening chorus

(No. 1).

Although this is not

a chorale text, Bach

treats it as if it

was. He lets these

words wander through

the piece like a red

thread (as in a

cantus firmus), and

actually uses it as

a musical motif,

which we clearly

recognise as the

famous “O Lamm

Gottes unschuldig”

(O innocent Lamb of

God). Through this

association of ideas

Bach, for his part,

will lead us to the

ulterior thought,

that Christ was

innocent when he

suffered death on

the Cross – and then

rose from the dead.

The opening chorus

is monumentally laid

out and deeply

thought through. The

richly coloured wind

group characterises

the sound of the

whole: a corno

da tirarsi

(literally a

‘pull-horn’, also a

‘telescopic horn!’)

introduces the

cantus firmus and

later reinforces the

soprano. It is

joined by a

transverse flute and

two oboes d‘amore,

which are placed in

dialogue or in

unison with the

vocal quartet or the

strings. The

instrumental

introduction almost

always anticipates

the following vocal

sections. Here Bach

plays with the

words. Thus he uses

the opening word “Halt”

(Hold) with a double

meaning. On the one

hand in the sense of

hold, keep,

always stay there

(which he achieves

through the long

held note at the

beginning of the

cantus firmus before

the related chorale

motif (O Lamb of

God) enters), and

meanwhile, on the

other hand, there is

the imperious effect

of the cry “Halt!”.

At the same time he

isolates it from the

next word, and

repeats it three

times clearly

separate, as a

triple signal. This

is actually also

appropriate here: halt,

go no further in

thy thoughts, stand

still ...

The “Hold in

remembrance”

is clearly

strengthened by this

“wordplay”.

Musically an

insistent figure

results from three

exclamations,

between which the

oboe begins to play

several ‘forlorn’

notes – a motif

which is broken off

(yes, a broken-off

thought: the “Halt”

stops so abruptly!)

After the third and

last “Halt”,

however, the broken

oboe motif finally

continues in regular

quavers (the picture

of reinstated

remembrances, which

holds the right

track?) After seven

bars like this, in

which the strings

have a contrapuntal

dialogue with

material from the

cantus firmus “Lamb

of God”, the

bass takes over the

cantus firmus and

the horn the running

quavers.

We hear this course

in three lightly

modified versions

one after the other,

first in the

instrumental

introduction and

then twice with the

singers. Then, in

bar 33, the vocal

ensemble starts a

kind of double fugue

with the basso

continuo, with the

cantus firmus as the

subject and the

running quavers as

the counter-subject.

There follows a

tutti section, in

which the woodwinds

double the singers

in a contrapuntal

web (like the

strings with each

other previously).

The higher strings

undertake the

running quaver motif

again, and the basso

continuo and the

horn have a dialogue

with the cantus

firmus material.

This very complex

piece (a

complete description

would be too long,

and hardly possible

to follow without a

score) is so

extremely varied;

the most amazing

construction, which

intends to stamp the

chief thoughts of

this Sunday‘s

liturgy deeply into

our minds.

Without an

intervening

recitative, the

Cantata continues

with an Aria

(no. 2) for

tenor and strings.

The poet points to

the terrible inner

division: “Mein

Jesus ist

erstanden –

allein, was schreckt

mich noch?”

(My Jesus is risen –

but, what frightens

me still?). Why do I

not stand firm in my

faith and still by

so many things would

be frightened (“...

doch fühlt mein

Herze Streit und

Krieg”) (...

still my heart feels

strife and war)?

Also I wish, like

Thomas, to see the

resurrected Jesus (“...erscheine

doch, mein Heil”)

(...yet appear,

my Saviour),

although my faith “des

Heilands Sieg kennt

...” (knows

of the Saviour‘s

victory). The mind

‘knows’ (or tries to

‘know’, makes a big

effort), though the

heart doubts and

knows fear and

distress.

Bach makes use of

the course of the

two first lines

clearly and

consistently: on “erstanden”

(risen) an upwards

run, and for “Allein,

was schreckt mich

noch” (But,

what frightens me

still), a sudden

skipped beat: a

sharply dotted

rhythm. Here also in

the introduction is

a precise portrayal

of the coming vocal

episode. Both

elements, the rising

line and the dotted

figure, are set in

the most varied

combinations in this

aria, which is by

and large restless.

Next comes a long Secco

Recitativo (nos. 3

and 5) for

alto, interrupted by

a Chorale (no. 4,

text by Hermans,

1560), in which the

poet addresses Jesus

himself about our

inner conflicts: how

is it possible that

“mich noch Gefahr

und Schrecken

trifft” (I

still meet danger

and terror) if Thou

hast overcome death?

We sing to Thee the

hymn of praise “Erschienen

ist der herrlich

Tag, usw.“

(Now dawns the

glorious day etc.)

(this is the

Chorale, no. 4, an

old Easter hymn),

but nevertheless my

enemies do not let

me rest in peace!

From here on,

however, the poet at

last thinks

positively, and

finally expresses

his confidence (“Ja,

wir spüren schon

im Glauben / Dass

du, O

Friedensfürst /

Dein Wort und Werk

an uns erfüllen

wirst” – Yea,

we already feel in

our faith / that

Thou, O Prince of

Peace / will fill us

with Thy word and

work).

After this triple

structure (nos.

3-4-5) there again

follows a three-part

text: the complex Aria

(no. 6) with

woodwind and

strings. In the

Baroque way, the

poet takes up the

last words of the

previous Secco

Recitativo: he now

brings on stage the

risen Jesus, and in

fact with those

welcoming words,

which he (according

to St. John‘s

Gospel) also

directed at the

disciples when

appearing to them: “Friede

sei mit euch”

(Peace be with

thee). Here, as

usual, the divine

words are sung by

the bass, the Vox

Dei (the Voice of

God). The poet lets

Jesus say these

words three times

(in St. John‘s

Gospel three

appearances are also

reported). After

each of these

‘greetings’, he

allows the group of

the faithful – in

the shape of the

three other singers

– to arrive with

their own poetic

reaction to the

word. They praise

Jesus, who helps

them to struggle and

to calm the fury of

their enemies (“hilft

uns kämpfen und

die Wut der Feinde

zu dämpfen”),

who refreshes both

spirit and body (“...erquicket

Geist und Leib

zugleich”),

and they beg for his

help to enter into

His glorious Kingdom

through death (“um

den Tod

hindurchzudringen

in dein Ehrenreich”).

Bach has ‘darkened’

the original

structure coming

from the poet in so

far as he allows an

instrumental

introduction to

precede the setting,

as already

anticipated by the

commentary of the

assembled company,

and anyway adds

another (fourth!)

greeting through the

Vox Dei as a

conclusion to the

whole. Musically the

impression of a

four-part structure

arises through this

(four times the

sequence of assembled

company / Voice of

God), while

earlier the text

produces a triple

change of Voice

of God/assembled

company.

Above all, Bach

emphasised in this

aria the contrast

between earthly toil

and distress on the

one hand (the

struggle, the

refreshment after

the fatigue, the

hope of the Kingdom

of Heaven), and on

the other hand the

universal wish for

peace through Jesus,

who towers over all

this. To heighten

the theatrical

effect he opens the

aria with a powerful

prelude for strings,

which portrays above

all the struggle.

This immediately

connects with the

first Vox Dei

greeting “Friede

sei mit euch”,

which is framed by

the transverse flute

and the two oboes.

After this ‘struggle

music’ they form

redeeming ‘heaven

music’ in a dense,

three-voice web,

which is accompanied

by a very spare

basso continuo. The

three other singers

(the assembled

company of the

faithful, in the

poet‘s words)

respond to the wish

for peace with “Wohl

uns, Jesus hilft

uns kämpfen” (Happy

are we, Jesus helps

us in the struggle)

etc.: the strings

unfold their warlike

motifs again and the

singers join in with

a lively imitative

counterpoint. Now

comes the second

wish for peace and

again the

three-voice

response: “Wohl

uns, Jesus holet

uns zum Frieden /

Und erquicket in

uns / Müden Geist

und Leib zugleich”

(Happy are we, Jesus

leads us towards

peace / and

refreshes both

spirit and body when

we are tired) (note

the long held notes

on “Müden”,

during the

continuing ‘warlike

notes’ of the

strings). Finally

the third wish

for peace, set for

bass with the high

wind, is followed by

the last commentary

of the assembled

company with the

strings “O Herr,

hilf und lass

gelingen” (O

Lord. Help us and

let us succeed) etc.

At the close as

already noted, Bach

puts an additional

greeting “Friede

sei mit euch”.

This device lends

the whole structure

a clear progression

from war and

strife to peace:

God‘s help for the

faithful (in the

libretto it was just

the other way

round).

At the same time, it

must be pointed out

that the

distribution of the

voices, which we

find here, can very

well be taken as an

argument that Bach

used only four

soloists for his

cantata

performances. Had he

actually had several

singers per register

at his disposal,

then the three-voice

writing (soprano,

alto, tenor), which

we find in the

polyphonic sections

between the bass

‘greetings’, would

hardly be

explicable, because

a full four-voice

choir would

certainly have been

natural here, if it

had been in

existence!

The Cantata closes

with a simple

four-part Chorale

(no. 7) to the

text of J. Ebert

(1601) “Du

Friedefürst, Herr

Jesu Christ”

(Thou Prince of

Peace, Lord Jesus

Christ), in which

the chief message is

that the Christian

should turn to Jesus

as a “starker

Nothelfer”

(strong Deliverer),

in whose name he

cries to the Father.

“Ich bin ein

guter Hirt”, BWV

85

(I am a good

Shepherd) for

Misericordias

Domini Sunday, the

15th April 1725.

The leitmotif of

this Cantata‘s text

also comes from St.

John‘s Gospel (ch.

10, 11-16), which is

read on this Sunday:

I am a good

Shepherd, and give

my life for my sheep

– where the ordinary

shepherd would allow

the attack of the

wolf on the sheep

and then these would

be killed.

The poet of this

text is also

unknown.

The Cantata begins

with the quotation

from St. John “Ich

bin ein guter

Hirt, etc” (I

am a good Shepherd,

etc) (no. 1).

As expected, such a

word of God is

spoken by the bass

alone (Vox Dei).

In this short aria

there is a dialogue

between a solo oboe

and the singer. (The

shawm, typical

‘shepherd

instrument’, is

regarded as the

archetype oboe).

In the introduction

we hear the theme in

the instrumental

bass, as it is later

heard five times in

the course of the

piece by the bass

singing “Ich bin

ein guter Hirt”

(the instrumental

bass actually plays

it in its original

form a total of

fourteen times.

Perhaps a hidden

Bach signature, the

sum of B+a+c+h, or,

‘converted’,

2+1+3+8, which makes

14? It would not be

the only time).

The oboe, after a

long held first

note, plays the

descending run of

semiquavers, which

will be the

fundamental

component of the

composition: the

Shepherd watches

from above, because

he is above

...! The run occurs

for the first time

on the words “lässt

sein Leben ...”

(gives his life),

which clearly

expresses the let

go, the giving

up. The aria

proceeds with a

lyrical flow, in

horizontal

polyphonic lines,

occasionally in a

six-part texture.

There follows an Aria

for Alto (no. 2)

with basso continuo

and obbligato Violoncello

piccolo –

therefore a Violoncello

da spalla

(shoulder cello),

here at a higher

pitch (G d a e‘, an

octave below the

violin pitch: the

possible fifth

string, for deep C,

is not called for

here and can be

omitted). The part

is actually entirely

imagined in the

violin idiom.

Bach used here the

contents of the text

as the foundation

for his composition.

He set himself up so

to speak as an

instrument which

must play the

introduction, whose

main theme is the

‘guarding’. As the

sheepdog constantly

circles round the

sheep in order to

watch over them, so

the Shepherd Jesus

cares for his sheep,

mankind. We find

this constant

‘encircling’ clearly

expressed musically

in the almost

unbroken semiquavers

of the solo

instruments. When

these are

occasionally silent,

the vocal soloist

takes them over with

a long vocalise on

the words “...

die ihm niemand

rauben wird”

(whom no one will

carry off): as if

Jesus is represented

as the watching

sheepdog.

In the following Chorale

Arrangement (no.

3) the

librettist uses the

first verse of a

psalm-hymn by

Cornelius Becker

(1598): “Der

Herr ist mein

getreuer Hirt”

(The Lord is my true

Shepherd). The two

oboes (again the

‘shepherd

instruments’)

present the melody

in a slightly varied

form in dialogue

over steady quavers

in the basso

continuo. In the

fourth bar the

continuo also takes

on the start of this

theme, while the

first oboe plays the

other important

motif (made up),

which later appears

time and again from

both oboes as a

‘framework’ for the

whole (this reminds

us anew of the

constant ‘guarding’,

as in the previous

aria). The soprano

soloist sings the

four lines twice in

separate blocks, in

which the melody is

slightly varied.

In the Accompagnato

Recitativo for

tenor (no. 4)

with strings, which

now follows, the

poet portrays the

scene in Baroque

language: the

‘hireling’ sleeps

(the ‘hired’

shepherd) and does

not keep watch, but

the good Shepherd

watches over his

sheep and leads them

to “wo die

Lebensströme

fließen”

(where the streams

of life flow). If

then “der

Höllenwolf kommt,

die Schafe zu

verschlingen”

(the wolf from hell

comes, to devour the

sheep) the Shepherd

will scare it off.

As is usual in such

an accompanied

recitative, some of

the strings also

illustrate it here:

thus the ‘watching’

(as lively fast

triplets) and the

‘flowing streams’

(as a horizontally

downward figure).

This is also

illustrated at the

close by the tenor

with the sudden,

large, upward

interval as revenge

is taken on the wolf

from hell.

The tenor

immediately goes

further with an

Aria (no. 5):

“Seht, was die

Liebe tut / Mein

Jesus hält in

guter Hut / Die

Seinen feste

eingeschlossen”

(See what love can

do. / My Jesus holds

with kindly care /

his flock securely

in his keeping).

Once again it is

noteworthy how Bach

is prepared to

arrange the contents

of the text like an

instrument, not

because he wishes to

portray every

episode (as if he

must above all be

‘painterly’, in

order to make a

story clear for the

listeners), but only

– as I believe at

least – so that the

medium used would be

sensibly measured

for or even

‘attached’ by

himself out of the

subject, even if

this was not perhaps

immediately apparent

from the first

hearing. What and

how the material is,

is just as important

as how Bach makes

use of it. Both

aspects are

inseparable and

therefore it is,

because of this

among other things,

impossible to

express in words the

true greatness of

his art, or indeed

of art in general.

(We also find in

many religions the

impossibility of

expressing the true

Name of God.)

The three string

parts (both violins

and viola) play

in unison, thus with

one sound. This idea

comes from the text

“feste

eingeschlossen”.

It would be normal

for the three to be

different from each

other. The start of

the text “Seht”

(See) is given

emphasis by Bach

letting the tenor

repeat it three

times separately

before continuing.

When the words “Mein

Jesus hält”

(My Jesus holds) are

heard for the first

time, Bach writes

three similar notes

strung together

(‘recto tono’). He

repeats this, when

on the words “Und

hat am

Kreuzesstamm”

(And had on the

Cross) the music

changes to the key

of the fifth, and

then continues with

a long vocalise on “vergossen”

(spilt), which is

repeated shortly

afterwards in rather

an extended form.

The ‘bleeding’ is

thus made noticeable

as an event in time

and space. The

melodic invention of

this movement seems

very ‘pastoral’: the

Shepherd inspires

the music ...

As a close to this

rather intimate

Cantata (there is no

great choral

movement!) we get a

verse from the hymn

“Ist Gott mein

Schild und

Helfersmann”

(God is 9 my Shield

and Helper) by Ernst

Chr. Homburg (1658):

“Ist Gott mein

Schutz und treuer

Hirt” (God is

my Protection

and True Shepherd) (chorale

no. 6). The

leitmotif of the

Shepherd is used as

a synthesis for the

last time. The

melody is no typical

simple chorale, but

rather the product

of a clearly later

aesthetic: it widens

out like a four-part

Baroque aria, with

evermoving voice

leading.

“Weinen, Klagen,

Sorgen, Zagen”,

BWV 12

(Weeping,

wailing, worrying,

fearing) is one of

Bach‘s early

Cantatas.

It was composed in

Weimar for the Jubilate

Sunday 22nd

April 1714, though

Bach performed it

again in Leipzig on

the 30th April 1724,

as is verified by

some sources. The

Weimar score is in F

minor, the Leipzig

notation was in G

minor. The

‘objective’ pitch

actually gives much

the same result,

because in the

Leipzig church,

music was made in a

lower key than

previously in

Weimar; but the

notes are

differently placed

in the instruments

(for example, the

open strings of the

stringed instruments

in the Leipzig G

minor are tuned to

different notes than

in the higher Weimar

F minor!), so one

has in fact the

impression of

another key. We have

chosen, for

practical reasons,

the Leipzig version,

and also decided to

keep the

instrumentation (as

well as the voices)

for this Cantata one-to-a-part.

In my opinion, this

corresponds more to

the style and

tradition in similar

pieces.

This Cantata feels

very typical of the

young Bach. For one

thing, in his Weimar

period he was

inclined towards a

definitely older

tradition (for

example the

five-part strings),

for another his

tremendous

imagination and the

directly expressive

power unfolded there

in full maturity,

which still

surprises us today.

The text comes from

the famous cantata

poet Salomon Franck,

with whom Bach

worked directly

after his

appointment as

concertmaster in the

Weimar court (BWV

182, 12 and 172).

Franck was born in

1659 in Weimar, and

also died there in

1724. After studying

law and theology he

became the Court

Librarian. As a poet

he wrote many

cantata poems from

1694, in which he

was sometimes

conformist. In his

later texts we find

him using the

familiar cantata

form, with

alternating arias

and recitatives, but

in the beginning he

confined himself to

bible texts combined

with his own verses.

Thus “Weinen,

Klagen, Sorgen,

Zagen” belongs

to his earlier

method of working.

The opening text

follows closely the

Gospel reading for Jubilate

Sunday (St. John,

ch. 16, 16-23), in

which it is said “Ihr

werdet weinen und

heulen” (Ye

shall weep and

lament). Then

follows a literal

quotation (from the

Acts of the Apostles

this time: ch. 14,

22) “Wir müssen

durch viel Trübsal

in das Reich

Gottes eingehen”

(We must through

much tribulation

enter the Kingdom of

God). Then come

three aria texts

from his own pen,

one after the other,

without intervening

recitatives (the

schemas with

recitatives are

mostly only found in

the later works). A

chorale verse by

Samuel Rodegast,

1675, the last verse

of his hymn “Was

Gott tut, das ist

wohl getan”

(What God does, that

is well done) closes

the work.

Bach opens the

Cantata with a Sinfonia

(no. 1) for

solo oboe with

five-part string

accompaniment (the

basso continuo is

strengthened by a

bassoon). In this

piece the lamenting

is prepared, which

we hear immediately

afterwards from the

singers. The two

violins sometimes

combine with the

richly ornamented

oboe cantilena, and

the separate viola

part maintains its

simple, regular,

quaver pulse

throughout the whole

piece. The bass

supports the whole

with slow strides

(like pillars under

the harmony). This

section is

reminiscent of the

first movement of

the E major Sonata

for Harpsichord and

Violin; although

this latter movement

is in the major it

shows the same

compositional

method. In its Affekt

this Sinfonia is

also very like the

oboe and strings

Sinfonia from the

Weimar Cantata “Ich

hatte viel

Bekümmernis”

(I am much

distressed) (BWV

21).

There follows the

real beginning of

the Cantata (no.

2, “Chorus”.

This movement is, as

required by the

text, a true Lamento,

entirely in the

tradition of the

preceding

seventeenth century.

The basic structure

is A-B-A. In the

A-part (marked Lente)

the instrumental

bass is a striding

figure of four bars

in 3/2 time, which

is constantly

repeated, a

so-called Ground,

which we find so

often in Purcell for

example, among

others. Here it is

the familiar Lamento

bass, a

chromatic descending

line, which closes

with a V-I (dominant

to tonic) phrase,

before starting

again. The four

upper voices

participate with

homophonic chords on

the first and third

beats, which are

very often

dissonant. The third

beat is left ‘blank’

each time, which

gives a melancholic,

sorrowful, ostinato

feeling to the

instrumental web. On

the second ‘free’

beat one of the four

singers gives a new

impulse to the text

almost every time.

So the beginning of

the Lamento is an

insertion (on the

second beat of the

bar each time) of

the words “Weinen

– Klagen – Sorgen

– Zagen” in a

descending sequence

presented by the

soprano-alto-tenor-bass.

From the third bar

the tenor begins the

sequence again, and

the voices overlap

more and more until

the full four-part

version develops,

which expresses the

words “Angst und

Not” (anxiety

and distress)

homophonically in a

lamenting harmony.

After this the

‘individual’ laments

from all the voices

start again (always

over the same

ground!), in which

very bold harmonic

turns come and go.

An instrumental

interlude (the last

time on the ground!)

leads into the

B-part (un poco

allegro) on

the words “die

das Zeichen Jesu

tragen” (who

bear the sign of

Jesus). This part of

the movement is

opposite to with the

above; a flowing and

very serene

polyphony, without

painful dissonances,

advances, until Bach

suddenly writes Andante,

and again, in a slow

tempo, a chromatic

(this time rising)

figure with trills

enters on the word “Zeichen”;

this short section

leads up to a repeat

of the Lente

Lamento.

Bach remembered the

unusual Lamento of

this Cantata, when

much later he

composed the “Crucifixus”

in the Credo of the

B minor Mass. He

transposed the whole

into E minor, added

two transverse

flutes, which play

together on the

second and third

beats (there is a

rest on the first),

and adapted the

Crucifixus text to

the existing

polyphony. The

instruments play

alone this time in

an introduction on

the ground with the

appropriate harmony.

So while the ground

is repeated 12

times in the Cantata

“Weinen, Klagen”

etc., this figure

appears in the

Crucifixus 13

times in the bass.

Speculatively, it

must be suspected

that Bach

incorporated his

‘name-number’ 14

(the sum of B-A-C-H

in the alphabet),

here deliberately

reduced by 1 (the crucifixus

of the dying Christ)

and thus his secret

signature. Or does

the 13 (instead of

12 in the original

version) have

another meaning?

Now follows an Accompagnato

Recitativo for

alto and strings (no.

3), on the

words from the Acts

of the Apostles (as

tradition wants,

edited by St. Luke),

ch. 14, 22: “Wir

müssen durch viel

Trübsal in das

Reich Gottes

eingehen” (We

must through much

tribulation enter

the Kingdom of God).

With these words –

or so, at least, it

says in the

Scriptures – Paul

and Barnabas

addressed the

Christian faithful

in Antioch, and

emphasized them

constantly to hold

on firmly to faith.

Bach repeats the

idea of the “Trübsal”

four times, each

time with expressive

harmony; the words “in

das Reich Gottes

ein(gehen)”

are sung very

significantly on an

ascending line.

The alto takes this

further in an Aria

(no. 4) with

obbligato oboe and

basso continuo.

Salomon Franck again

takes the main motif

of his text from the

Holy Scripture: “Kreuz

und Krone sind

verbunden”

(Cross and Crown are

joined together),

see Revelations ch.

2, 10, where St.

John says: “seid

getreu bis in den

Tod, so will ich

euch die Krone des

Lebens geben”

(be thou faithful

unto death, and I

will give thee the

crown of life); “Kampf

und Kleinod sind

vereint”

(struggle and

treasure are

united). He alludes

so to the First

Epistle to the

Corinthians (ch. 9,

24). There Paul says

that, in the

stadium, all the

athletes run, but

only one receives

the prize – the Kleinod.

Again, the

continuing effort

needed to “reach the

Kingdom of God” is

described.

The alto and the

oboe develop their

dialogue over a calm

walking bass. A

couple of times they

interfere with each

other in their

‘conversation’. The

music does without

descriptive elements

to a large extent,

and remains abstract

in its layout. With

some effort,

however, one can

imagine in the

opening motif the

horizontal and

vertical lines of

the Cross, expressed

through its sudden

downward fall (of a

seventh) and the

immediate return to

the higher tessitura

in the middle of the

opening horizontal

motif.

Without an

intervening

recitative it is

followed by the Aria

for Bass (no. 5)

with two violins and

basso continuo. The

portrayal of the

difficult

requirements finally

gives way here to

the resolve of the

faithful to set out

on the road: “Ich

folge Christo

nach, von ihm will

ich nicht lassen”

etc. (I follow in

the steps of Christ,

I will not abandon

Him etc.). A

constantly recurring

rising line from all

the parts involved

one after the other,

heard at first

canonically,

illustrates the

words “Ich folge

Christo nach”.

This aria breathes

life into the firm

intention, “Christi

Schmach zu küssen,

und das Kreuz

umfassen” (to

kiss Christ’s

humiliation, and

to embrace his

Cross), as the poet

phrases it. We hear

a concertante

structure with two

high and two low

parts; in the

instrumental

interludes the

traditional trio

sonata appears not

to be too far away.

Again without a

recitative being

pushed in between

(we hardly ever come

across this in the

later recitative

cantatas) a third Aria

(no. 6)

follows, this time

for tenor and basso

continuo, with

obbligato tromba

(da tirarsi),

thus a ‘slide

trumpet’! The text

reads “Sei

getreu, alle Pein

/ Wird doch nur

ein kleines sein”

etc. (Be true, all

suffering / will

then be only a small

thing etc). Here we

encounter again

Bach’s deep

immersion in the

text. The “Sei

getreu” is

almost performed by

the basso continuo,

in that it repeats

it as a continual

obbligato motif,

that actually

submits itself to

the vocal part as in

true

‘service’, at the

same time always

remaining at a

distance and never

being concurrent.

The tenor voice on

the other hand is

very lyrically

melodic and is

central to events;

it attracts all

attention to itself

and also transmits

the text. Finally

the tromba frames

the whole with the

wordless performance

of the slightly

ornamented chorale

melody “Jesu

meine Freude”

(Jesus my joy). For

the experienced

listener this was

immediately

recognisable. The

profound closeness

of this (hidden!)

text with the sung

text is obvious.

Incidentally, the

sentence from

Revelations comes

through at the

beginning of this

aria, which we have

already heard in the

alto aria (no. 4): “seid

getreu” (...

so I will give you

the crown of life).

So this aria is an

example, of how Bach

is able to bring

three absolutely

independent lines

together in one

unique and wonderful

whole – a kind of

Trinity.

The Closing

Chorale (no. 7)

is a simple movement

“Was Gott tut,

das ist wohlgetan”

(What God does, that

is well done), by

Samuel Rodigast,

1675, to which Bach

exceptionally added

an independent

instrumental descant

in the high

register, which was

presumably meant for

the tromba da

tirarsi (the sources

which have come down

to us do not show

clearly who should

play it). Does it

not symbolise the

royal, divine

accompaniment to our

journey through

life?

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|