|

|

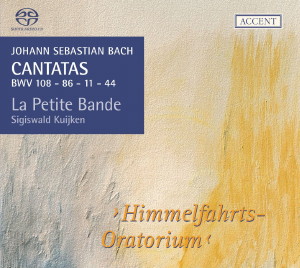

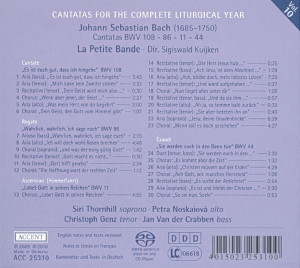

1 CD -

ACC 25310 - (p) 2009

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25310 - (p) 2009 - rectus

|

|

CANTATAS -

Volume 10

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4th Sunday after Easter

(Cantate) |

|

|

|

"Es ist euch gut,

dass ich hingehe", BWV 108

|

|

14' 21" |

|

| -

Aria (bass): Es ist euch gut,

dass ich hingehe |

3' 45" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Mich kann kein

Zweifel stören |

3' 32" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Dein

Geist wird mich also regieren |

0'

30"

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Wenn aber jener, der

Geist der Wahrheit |

2' 27" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Was mein Herz

von dir begehrt |

3' 00" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Dein Geist, den Gott vom Himmel

gibt |

1' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5th Sunday after Easter

(Rogate) |

|

|

|

| "Wahrlich,

wahrlich, ich sage euch", BWV 86 |

|

13' 01" |

|

| -

Arioso (bass): Wahrlich,

wahrlich, ich sage euch |

2' 15" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Ich will doch

wohl Rosen brechen |

4' 48" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Und was der ewig gütig Gott |

1' 42" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Gott

macht es nicht gleichwie die Welt |

0' 30" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Gott hilft

gewiß |

2' 34" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Die Hoffnung wart der rechten Zeit |

1' 12" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Himmelfahrt-Oratorium

(Ascension) |

|

|

|

| "Lobet Gott in

seinen Reichen", BWV 11 |

|

28' 40" |

|

| -

Chorus: Lobet Gott in seinen

Reichen |

4' 55" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Der Herr

Jesus hub seine Hände auf |

0' 25" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Ach Jesu,

ist dein Anschied schon so nah? |

1' 09" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Ach, bleibe

doch, mein liebster Leben |

7' 25" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Und ward

aufgehaben yusehends |

0' 27" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Nun lieget alles unter dir |

1' 05" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor, bass): Und

da sie ihm nachsahen... |

0' 57" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ah ja, so

komme bald zurück |

0' 33" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Sie aber

beteten ihn an |

0' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Jesu, deine

Gnadenblicke |

6' 29" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Wenn soll es doch

geschehen |

4' 27" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6th Sunday after Easter

(Exaudi) |

|

|

|

| "Sie werden euch

in den Bann tun", BWV 44 |

|

17' 44" |

|

| -

Duet (tenor, bass): Sie

werden euch in den Bann tun |

3' 20" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Es kommt aber die

Zeit |

1' 32" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Christen müssen

auf der Erden |

4' 29" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ach Gott, wie manches

Herzeleid |

1' 06" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Es sucht

der Antichrist |

0' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Es ist und

bleibt der Christen Trost |

5' 30" |

|

|

| -

Choral: So sei nun, Seele,

deine |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Siri Thornhill,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin (leader) |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Makoto Akatsu, violin |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Katharina Wulf, violin |

|

|

- Annelies Decock,

violin

|

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Hervé Douchy, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Marc Hantaï, traverso |

|

|

- Yifen Chen, traverso |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe |

|

|

- Vianciane

Baudhuin, oboe |

|

|

- Rainer Johannsen,

fagott |

|

|

- Jean François

Madeuf, trumpet |

|

|

- Joël Lahens, trumpet |

|

|

- Graham Nicholson,

trumpet |

|

|

- Koen Plaetinck, timpani |

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - 30 April / 1

May 2008 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25310 - (1 CD) - durata 73'

23" - (p) 2009 (c) 2010 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

Bach

Ascension Oratorio

and Cantatas BWV

108, 86 and 44

The Ascension of

Christ is

central to the

Christian credo.

Forty days after the

Feast of the Resurrection

(Easter) the

church celebrates

the Feast of the

Ascension; ten days

after that is

Whitsun, when the

sending of the Holy

Ghost from Heaven to

the Apostles is

celebrated (the

illustrations show

the Apostles and the

Mother of God with

small flames around

their heads, as a

symbol of

“enlightenment”!).

One Sunday later

still (Trinity) the

faithful celebrate

the now complete Trinity:

Father – Son –

Holy Ghost.

The cycle, which

began with Advent,

the coming of Jesus

Christ the Son of

God, is complete.

This recording

contains the

Cantatas for the fourth,

fifth and sixth

Sundays after

Easter, and the

Oratorio for the

Feast of the

Ascension, which

occurs on the

Thursday between the

fifth and the sixth

Sunday.

Certain Sundays in

the church year are

specially named, and

so named, in fact,

after the opening

words of the Latin

Introitus hymn

for the respective

Sunday services: so

these three Sundays

mentioned above are

Cantate,

Rogate

and Exaudi.

Traditionally the

gospel readings for

the third Sunday

after Easter (the Jubilate

not included here)

up to Whit Sunday

come from fragments

of the great sayings

of Jesus, as noted

by St. John. The

essential passages

(chaps. 12 to 17)

cover the time from

Jesus’s entry into

Jerusalem to the

start of the

Passion.

On “Cantate”

Sunday it comes from

St. John ch. 16, v.

5-15, with the key

passage “Wenn

ich nicht weggehe

von Euch, dann

kommt auch der

Helfer (Tröster)

nicht zu Euch”

(If I go not away,

the Comforter will

not come unto you).

St. John alludes

here to the

forthcoming events

(Passion,

Crucifixion,

Resurrection,

Ascension and

finally Whitsun,

when the Holy Ghost

appears).

On “Rogate”

Sunday St. John ch.

16, v. 23-30 is

read. There it is

written: ”Wahrlich

ich sage euch: was

ihr vom Vater

fragt in meinem

Namen, wird er

euch geben”

(Verily, I say unto

you, Whatsoever ye

shall ask the Father

in my name, he will

give it you).

On “Exaudi”

Sunday (the Sunday

after Ascension Day)

St. John ch. 15, v.

26 to ch. 16, v. 4

is read; here are

rather unwelcome

words: “Man wird

euch aus den

Synagogen

verbannen wegen

eures Zeugnisses

über mich”

(They shall put you

out of the

synagogues, because

of your witness of

me), and, even

worse: “Es kommt

eine Zeit, wo

derjenige, der

euch tötet,

glauben wird, er

tue eine Tat der

Gottesverehrung”

(The time cometh,

that whosoever

killeth you will

think he doeth God

service).

The titles of the

three Cantatas for

these Sundays

indicate their main

themes:

BWV 108 “Es ist

euch gut, dass ich

hingehe” (It

is good that I leave

you) (Cantate)

BWV 86 “Wahrlich,

wahrlich, ich sage

euch” (Verily,

verily I say unto

you) (Rogate)

BWV 44 “Sie

werden euch in den

Bann tun”

(They will

excommunicate you) (Exaudi)

The text of the Ascension

Oratorio (BWV

11) is based on

passages from

various New

Testament books: The

Gospel according to

St. L uke, The Acts

of the Apostles and

The Gospel according

to St. Mark, in

which the Ascension

is described.

“Es ist euch gut,

dass ich hingehe”,

BWV 108

(For Cantate

Sunday, 29th May

1725)

The text of this

Cantata comes from

Christiane Mariane

von Ziegler,

an exceptional woman

who led an eventful

life. She was from a

respected family,

born in Leipzig in

1695, married at 16,

widowed after a few

years, married again

and lost her second

husband after a few

years as well as the

children from both

husbands. Aged 27

she was living again

in the parental

home. She developed

her inborn feeling

for art, played

several musical

instruments and made

her house a meeting

place for artists

from the most

different

directions. Since

the arrival in

Leipzig of the

well-known poet and

theorist Gottsched

in 1724, she created

for herself a

distinctive image

through her literary

talents. In 1728 and

1729 she published

two collections of

poems and in 1731 a

collection of

letters. Her work

then became

academically

recognised, she

married for a third

time in 1741 and

died in Frankfurt in

1760.

Bach set nine of her

cantata texts. She

published these nine

later, in 1728 (“Versuch

in gebundener

Schreib-Art ”).

In this connection,

it must be noted

that Bach sometimes

amended her verses

in his cantatas –

often without even

respecting the

rhymes – he

apparently had other

priorities of

form...

The Cantata starts

with a literal

quotation from St.

John ch. 16, v.7: “Es

ist euch gut, dass

ich hingehe”

etc. (It is good

that I leave you).

Here this is

considered to be the

Word of God,

so Bach puts it, as

he does

occasionally, in the

mouth of a basso

solo as VOX

DEI (the voice of

God), not as an

opening chorus with

the complete vocal

quartet. This piece

(No. 1) is no

ordinary aria,

because the St. John

quotation is not set

as a poem but as a

prose text. It is

also not in the

usual da capo form.

Very often with Bach

such Vox Dei words

are conceived as a dialogue

with an instrumental

soloist. To

the rather

‘imperious’ phrase

of God belongs,

almost

self-evidently, the

tromba (which

clearly suggests the

image of God, and

which, even today,

is also sometimes

dominant, with God

as a human King,

whose authority is

expressed with an

almost military

splendour). This

section of text,

however, has none of

the character of an

Old Testament

Commandment – quite

the opposite: it is

rather a mystery for

the listener. The

power and splendour

of the trumpet would

not be appropriate

here. Yet here Bach

also ‘doubles’ the

statement of the

text, dividing it in

a dialogue with ...

Yes, with whom?

Above all, I would

say, with our

‘soul’, with our

inner selves. Here

there is a dialogue

between the oboe

d’amore and

the Vox Dei. Grant

me the naïve thought

that, with the

decision to use a d’amore

instrument for the

Voice of God, Bach

actually wants to

remind us of the Love

of God. The Baroque

artist does not shy

away from such

simple associations,

and neither does

Bach.

The instrumentation,

with the bass

striding steadily

wider, clearly

suggests the

‘going’, thus the

‘going away’ here.

On the words hin gehe

and sende

Bach writes long

onamented melismas

for the singer. They

had already been

announced in the oboe

d’amore-introduction, and strengthen the vivid picture, thus

creating even more

strongly the

unconscious echo in

our inner self.

The whole piece is a

wonderful

combination, on the

one hand, of a

distinct description

of the passage of

time (the ‘march’ in

the basso continuo)

and, on the other

hand, an extremely

lyrical dialogue

between the two main

voices.

No. 2 is an Aria

for Tenor,

with a solo violin

and basso continuo.

Here the poetess

(Mariane von Ziegler)

‘answers’ the Voice

of God. (Though here

Bach ‘doubles’ the

text with the help

of the solo violin,

which plays in

dialogue with the

tenor). The poetess,

without in the least

doubting the Word of

God – thus also

comforted, declares

that she will share

in the Redemption

through the

Ascension of Jesus.

“Mich kann kein

Zweifel stören

...” (No doubt

can disturb me). The

busy violin part

illustrates well the

doubting search, and

the tenor in his

melismas likewise

describes the

concept of Zweifel

(doubt) and stören

(disturb): unusual

intervals follow one

after another in the

vocalise – until

suddenly there is a

standstill on a long

note for the words “ich

glaube”. The

violin also imitates

this point of rest

in its part. The

meaning of the words

“gehst du fort”

(goest thou away)

and “Erlösten”

(the redeemed) are

also portrayed.

Under the dialogue

there beats a

regular tempo, which

for the first ten

bars again and again

falters through a

quaver rest on the

third beat: the

doubt? the

disturbance?

This rhythmical form

in the bass line

accompanies the

whole aria, and in

large measure

decides the affekt

of the piece.

No. 3, Secco

Recitative for the

tenor, now

follows, with a

typical Baroque

expression, “durch

Dein Hingehen wird

also der Geist zu

mir kommen”

(thus, through Thy

going, the Spirit

comes to me). It is

a skilful

introduction to No.

4 (Chorus):

once again a literal

quotation from St.

John’s Gospel (ch.

16, v. 13). It is a

three-part verse,

which Bach also

clearly structures

in three parts: “Wenn

aber jener, der

Geist der

Wahrheit, kommen

wird, der wird

euch in alle

Wahrheit leiten. /

Denn er wird nicht

von ihm selber

reden, sondern

das, was er hören

wird, das wird er

reden; / und was

zukünftig ist,

wird er

verkündigen”

(Howbeit when he,

the Spirit of truth,

is come, he will

guide you into all

truth: for he shall

not speak of

himself; but

whatsoever he shall

hear, that

shall he speak: and

he will shew you

things to come).

This text is once

again rather

enigmatic and

abstract in its

middle section; I

think that here St.

John is suggesting

the ineffable core

of the mystical

Trinity: “der

Geist wird nicht

aus sich selber

reden, sondern nur

das vermitteln,

was er vom Vater

und dem Söhne hat

...” (the

Spirit will not

speak his own words,

but only transmit

what he has from the

Father and the Son).

This relatively long

prose fragment is a

subject matter which

is not simple to set

– it is a

theological

statement, for which

neither poetic

metaphorical language

nor lyrical excess

would have led

directly to a

musical setting.

Bach treated the

three sections of

the St. John

quotation in three

short rather

objective sounding

fugatos, each with

its own theme – of

which the third is

clearly derived from

the first. The

natural word accents

of this Lutheran

translation of St.

John’s text are

strictly respected

in Bach’s setting.

Thus he writes

music, which appears

rather

‘instrumental’, of

great intellectual

power and beauty,

but which can also

fascinate

‘unpractised’ ears.

The instruments here

are just used to

double the voices –

only the basso

continuo at the

beginning of the

second and third

sections is briefly

heard independently

under the theme.

Now follows an Aria

for Alto,

Strings and Basso

Continuo (No. 5)

“Was mein Herz

von dir begehrt /

Ach, das wird mir

wohl gewährt”

etc. (What my heart

desires from Thee /

Ah! that will

certainly be granted

to me). The text by

Mariane von Ziegler

consists of three

verses of two lines

in trochaic metre

(long/short).

The ‘key words’

which Bach has

chosen to influence his

design are:

- in the

first two lines

the word “begehrt”

(desires);this idea

is emphasised by

constantly

breaking therhythmic

impulse (which

incidentally

reminds us

of a

minuet); the

‘desire’ is of

course the

longing

after a

‘something’

which is still ‘missing’,

and with

the

moment of

breaking each

time the

“missing” is

expressed,

that is to say even

through the

failing.

- in the

two following

lines “Überschütte

mich mit

Segen

/ Führe mich

auf deinen

Wegen”

(Overwhelm

me with

blessings / Lead

me in Thy way)

the word

“Überschütte”;

as if looking

forward, there

is a

long spun

out line

in continuous

rhythm – a

highly

imaginative

description. It

is already

indicated by

the first

violin in the

middle of the

fifth bar, and

repeated

often

throughout the

whole piece.

- in the

last two lines (“Dass

ich in der

Ewigkeit /Schaue

deine

Herrlichkeit”

– That I,

through all

Eternity

/ behold Thy

Glory) the word

“Ewigkeit”,

which is

underlined by

the soloist with

a long-held

note.

Incidentally,

this note was

already present

in

the

instrumental

introduction,

but, on first

hearing,

we do not

know its meaning

until later.

With

these three main

components Bach

devises an endless

number of

combinations in this

aria. Noteworthy

also is the

beautiful upward

swinging figure on “Schaue”

(behold) (the eyes

will be led upwards

as it were!). This

aria does not have

the traditional da

capo form in the

treatment of the

text; though it

comes full circle

with the

instrumental opening

repeated as the

‘ending’.

A simple Chorale

(no. 6) closes

the Cantata (1653,

Paul Gerhardt). It

emphasizes very

appropriately the

way shown by the

power of the Holy

Ghost.

“Wahrlich,

wahrlich, ich sage

euch”, BWV 86

For Rogate

Sunday, the 14th

May 1724.

The words in St.

John ch. 16, v. 23 “Wahrlich

ich sage euch: so

ihr den Vater

etwas bitten

werdet in meinem

Namen, so wird

er’s euch geben”

(Verily, I say unto

you, Whatsoever ye

shall ask the Father

in my name, He will

give it you), which

is found in the

Gospel reading for

this Sunday, is the

leitmotif of the

whole Cantata. The

anonymous poet

emphasizes the

absolute confidence

in the validity of

this statement by

Jesus which the

Christian ought to

have. But still it

indicates best how

little it is given

to mankind to know when

exactly the

gift will take

place; only God

knows this best...

The St. John text is

presented first by

the Bass Solo

(No. 1),

accompanied by the

four strings. Again

we hear the Vox Dei

– here it is woven

into five voices for

the most part. The

piece is conceived

in the strict old

polyphonic style,

with a ‘Quinta Vox’

as the only sung

part. The main

theme, which follows

the prosody of the

words exactly, is

always bound

compositionally to

its counter-subject

(Dux and Comes). A

superb example of

Bach’s unsurpassed

contrapuntal style!

There follows an Aria

(no. 2) for

Alto, with violin

solo and basso

continuo: “Ich

will doch wohl

Rosen brechen /

Wenn mich gleich

die Dornen

stechen” (Yet

I will gladly pick

roses / even though

the thorns prick

me). With this

picture the poet

declares that if the

Christian who gets

into difficulties

trusts in God

(behind the thorns,

roses!), then God

keeps his given

word. The violin

part is very active,

with passaggi

and arpeggi

surely symbolising

the work, the

difficulty (although

Dürr’s

interpretation could

also be valid: he

sees in this violin

part more the

radiance of God over

all earthly

hardship). In

addition the voice

in the A-part has

quite a lot of

broken lines (the picking,

pricking?) -

in the B-part, on

the other hand, (“Denn

ich bin der

Zuversicht, dass

mein bitten und

mein flehen / Gott

gewiss zum Herzen

gehen ...” –

Then I am confident

that my prayers and

my pleading / to God

will surely go to

His heart) the line

is more supple and

lyrical.

After this comes a Chorale

arrangement (No.

3) for soprano

with two oboes

d’amore and basso

continuo of verse 16

of the hymn “Come

here to Me, saith

the Son of God” by

Georg Grünwald

(1530): “Und was

der ewig gütig

Gott / In seinem

Wort versprochen

hat” etc. (And

what the eternally

just God / has

promised by his

word). The joyful

three-part

instrumental

movement contains

the chorale melody

in long notes, like

a cantus firmus –

thus one could think

of the Trinity,

which protects

mankind.

A Secco

Recitativo for

Tenor (No. 4)

wants to stress the

faithfulness of God

even more, and

actually does so

through a negative

comparison with the

“world / which

promises much and

does little” (“...

Welt / die viel

verspricht und

wenig hält”).

The recitative leads

directly into the Tenor

Aria (No. 5)

with strings “Gott

hilft gewiss”

(God’s help is

certain), whose affekt

was already

announced in the

last line of

recitative through “Lust

und Freuden”

(pleasure and joy).

The first violin has

an intensive

dialogue with the

solo voice, the

other strings

supporting them. The

B-part of the aria

states more

precisely: “Wird

gleich die Hülfe

aufgeschoben /

Wird sie doch drum

nicht aufgehoben”

(If the help is put

off / it does not

mean that it will

not happen); once

again we are bidden

to have patience and

trust.

This Cantata is

closed with a simple

Chorale (No. 6):

verse 11 of the hymn

“Now has salvation

come to us” by Paul

Speratus (1523) “Die

Hoffnung wart’ der

rechten Zeit / was

Gottes Wort

zusaget” (Hope

awaits the right

time / for what the

Word of God

promises) – which

once again

summarizes the main

theme.

“Lobet Gott in

seinen Reichen”,

BWV 11

(Ascension

Oratorio, 1735)

For the Feast of the

Ascension Bach has

left us four

liturgical works,

and all of them were

written in Leipzig

(1724, 1725, 1726

and 1735). The

Ascension Oratorio

is thus the last of

the series.

By 1735 Bach had

composed several

oratorios, with

texts largely from

the hand of

Picander, whom we

also know as the

librettist of the

St. Matthew Passion

(mind you, at that

time the Ascension

Oratorio was not

included in the

collected edition of

Picander’s poetry;

which gives rise to

some doubt about his

authorship). These

Oratorios are not

fundamentally

different from the

‘normal’ cantatas.

It is typical that –

as in the Passions –

an Evangelist

(the tenor) appears,

who recites the

words of the episode

from the Gospels.

Then around these

words the whole web

of the work is

developed further,

with arias,

accompanied

recitatives,

choruses and

chorales. Thus there

emerged the

Christmas Oratorio

(which in reality is

a series of six

cantatas), the

Easter Oratorio (a

modification of an

earlier Easter

Cantata) and this

Ascension Oratorio.

The assembled text

use quotations from

the Gospels of St.

Mark and St.

Luke, as well

as the Acts of

the Apostles.

These fragments are

thus adopted

literally and/or

combined; in

addition to that it

had separate verses

composed, as

‘commentary’ or

moments of prayer.

As a third layer of

text there are

included – as in all

cantatas – old

church hymns

(chorales). The

first part closes

with a simple

Chorale – the second

part, in contrast,

with a wide-ranging

concertante piece,

which encircles a

Chorale.

In this church

piece, which was

first heard on the

19th May 1735, Bach

borrowed much from

his earlier works –

which it is known he

often did, and which

is no discredit, for

the new version

always fits

perfectly into the

new surroundings.

- The

opening chorus

is an adaptation

of the opening

chorus from a

secular cantata

“Froher Tag,

verlangte

Stunden”

(Happy Day,

longed-for

hours), written

for the

dedication of

the renovated

School of St.

Thomas in

Leipzig in

1732), the music

of which is

lost.

- The two

arias are

adaptations from

arias of a

wedding cantata

of 1725 “Auf,

süß

entzückende

Gewalt”

(Up, sweet

delightful

force) with a

text by

Gottsched. The

music of the

original has

also gone

missing.

The

Opening chorus

(No. 1) of

this Ascension

Oratorio has as

‘new’ text “Lobet

Gott in seinen

Reichen”

(Praise God in his

kingdoms) – a text

in trochaic metre,

which appears to

come from an old

psalm, but yet is by

the librettist

(Picander?). The

music fully matches

the contents of the

text with trumpets

and drums. A richly

colourful

instrumental

introduction

precedes the

homophonic entry of

the solo voices, who

soon let the “Lobet”

ring out one after

the other in

imitation, giving a

three-dimensional

effect, as if

several singing

angels were in the

sky. In the second

half, at “Sucht

sein Lob recht zu

vergleichen“

(Seek to compare His

praise properly),

the “seek” is

illustrated in the

soprano part with

shaking syncopation.

The whole works in a

very concerto-like

and brilliant

fashion.

Then follows the

first Secco Recitativo

for the Evangelist

(No. 2), after

St. L uke ch. 24, v.

50 and 51: “Der

Herr Jesu hub

seine Hände auf“

(The Lord Jesus

lifted up his

hands). Here the

basso continuo

depicts the blessing

with a rising phrase

and, at “da er

sie segnete”

(as he blessed them)

with a downward

phrase. This is an

extremely simple

description, yet

Bach did not wish to

do without it!

Jesus blessed his

disciples and scheidet

von ihnen

(parted from them),

as it is told in the

text. The Ascension

itself is not yet

mentioned here – the

poet will imagine

the departure

for the first time

in a passionate

accompanied

recitative (No. 3)

and a touching aria

text (No. 4).

The Accompanied

Recitative (No. 3)

is assigned to the

bass voice, in which

it is accompanied by

two transverse

flutes and basso

continuo. The text

is full of

rhetorical questions

and answers, as was

proper in the

Baroque era. The

flutes, with groups

of soft staccato

semiquavers,

illustrate the “heißen

Tränen die von den

blassen Wangen

rollen” (hot

tears which roll

down pale cheeks);

frequently the

number of these

notes is exactly the

same as the number

of syllables in the

preceding text; so

one can describe,

for example, the

first group as an

‘echo’ of the words

“ist dein

Abschied schon so

nah?” (is Thy

departure already so

close?).

The following Aria

(No. 4) for Alto

with the violins and

basso continuo later

formed for Bach the

basis for his famous

Agnus Dei in

the B minor Mass.

This version of the

aria in the

Ascension Oratorio,

however, is already

(as noted above) an

arrangement from a

missing secular

cantata of 1725. The

Agnus Dei is

a second arrangement

of the original.

The text of the

present aria springs

from the idea of the

Abschied (parting):

“Ach bleibe doch,

mein liebstes

Leben / Ach fliehe

nicht so bald von

mir!” (Ah,

just stay, my

dearest life / Ah,

flee not so soon

from me!) etc. It is

a true Lamento, in

which the solo

singer and the

violin carry on a

close dialogue,

supported by the

slow and steady step

of the basso

continuo. This music

speaks of a mute

‘incomprehension’, a

kind of calm

sadness. The

disciples of Jesus

did not really

understand what was

happening, but would

feel how

irreversible his

parting was, would

beg him to stay,

although they would

see that he is going

away (whither they

still would not know

for the present).

The violins set the

tone in a long

introduction; the

alto starts with the

same violin motif,

but soon stops, in

order to let the

violins continue; he

repeats his opening

and afterwards

resumes the dialogue

with the violins. A

short interlude

leads to the B-part

of the aria, “Dein

Abschied und dein

frühes Scheiden /

Bringt mir das

allergrößte Leiden

/ Ach ja, so

bleibe doch noch

hier” (Thy

farewell and Thy

departure / brings

me the greatest

sorrow / Ah truly,

just stay here for a

while). A new motif

is soon heard in

both parts. For a

while there is a

parallel movement,

but soon the violins

fall back to the sad

Lamento motif from

the A-part; the alto

once again brings in

a new motif answered

by the violins,

after which the

Lamento begins

again. The aria ends

with a quasi da

capo of the

A-part.

Allow a short

examination here of

this particular aria

with regard to its

later re-use as Agnus

Dei. Here the

departure of

Jesus is

described – in the Agnus

Dei, however,

the Ascension has

already taken place,

and this departure

from the world

became to sit on

the right hand of

God, and an existence

as the Lamb of God.

This new connection

corresponds to an

important adaptation

of the Agnus

in the B-minor Mass,

compared to its

position in the

Ascension Oratorio

aria; the alto

begins the Agnus

with a completely new

motif, which does

not stem from

the violin

introduction:

instead of common

experience with the

parting (the aria in

the Ascension

Oratorio) the Agnus

essentially shows a

reality on two

levels – as if

the singer moves in

a different world to

the instruments. The

Jesus who ascends to

heaven becomes for

the faithful the Lamb

of God (Agnus Dei)

in heaven. By using

this aria again as

the Agnus Dei

in the B-minor Mass,

the devout Bach

shows us, in his own

way, how the

Ascension led to the

Glorifcation.

After these two

lyrical moments by

the poet (the

accompanied

recitative and aria)

there is a simple Secco

Recitative (No. 5)

by the Evangelist

(Tenor), which

relates the story

with words from Holy

Scripture (Acts of

the Apostles ch. 1,

v. 9 and St. Mark

ch. 16, v. 9): “Und

ward aufgehaben

zusehends und fuhr

auf gen Himmel;

eine Wolke nahm

ihn weg vor ihren

Augen, und er

sitzet zur rechten

Hand Gottes”

(and he was rapidly

taken up and

ascended unto

heaven; a cloud

received him out of

their sight, and he

sits on the right

hand of God).

There follows a

simple Chorale

(No. 6) “Nun

lieget alles unter

dir” (Now all

is subject to Thee)

by J. Rist (the

fourth verse of the

hymn Thou Prince

of Life,

Lord Jesus Christ,

1641). The hymn is

in triple time; this

gives it an almost

folk-like appeal.

The astonishment

about the

extraordinary events

of the Ascension

(here quite

certainly understood

as an actual

physical happening)

is apparent here.

The Evangelist

(7a) now tells

how suddenly, after

the actual

Ascension, two

men in

white apparel

appeared (as stated

in the Acts of the

Apostles ch. 1, v.

10-11), who

proclaimed to the

Apostles that the

ascended Jesus would

return as they had

previously seen him

go into heaven.

Here Bach allows the

Evangelist (tenor),

together with the

bass, to present the

words of the two men

as a duet. This is

an example that

shows, in Bach’s

concept, the

Evangelist is not only

the Evangelist

absolutely. He also

sings words which

are outside

his rôle. One can

see in this a

confirmation of the

practice, in

general, of working

with only four

singers and no

chorus in the

modern sense. It

would in fact have

been quite simple

and obvious to give

the rôle of the two

men to two other

singers, if they had

been available...

The duet of the two

men changes in bar 8

to a canon at the

fifth, which

announces “Dieser

Jesus... wird

kommen wie ihr ihn

gesehen habt gen

Himmel fahren”

(This Jesus ... will

return, just as you

have seen Him ascend

to Heaven). The

canon draws a

picture of the later

coming. The

first voice actually

comes back

to the identical

second entry – once

again an example of

how Bach takes his

idea of form from

the content of the

text.

Next, in an Accompanied

Recitative (7b)

with transverse

flutes, the poet

describes, in a

truly Baroque

gesture, devout

mankind, which, with

passionate

impatience, awaits

the imminent return

of Jesus. (Komme

bald, ... sonst

wird mir jeder

Augenblick verhaßt

und Jahren ähnlich

werden – Come

soon, ... else every

moment will be

hateful to me and

the years will be

the same).

After this

accompanied

recitative the Evangelist

(7c) carries

on relating the

Epilogue of the

events, as the

Apostles with

great joy

return to the city

of Jerusalem.

After this narration

of the key events of

the Oratorio, there

follows another kind

of epilogue: an aria

for Soprano solo,

which has obbligato

wind, as does the

closing chorus.

The Soprano Aria

(No. 8) is

accompanied by two

transverse flutes in

unison and an oboe,

with violins and

viola in unison as

an octave higher

‘bassetto’ (the bass

instruments are

silent). Bach had

taken this piece

from the Wedding

Cantata (“Auf!

süss entzückende

Gewalt” – Up!

Sweet delightful

force – of 1725,

text by Gottsched),

from which the

earlier aria No. 3

also came. The

Gottsched text of

this aria was called

“Unschuld,

Kleinod reiner

Seelen”

(Innocence, jewel of

pure souls). These

words had inspired

Bach in 1725 to work

only with the high

instruments (the childlike

innocence?),

and with the bass

instruments an

octave higher than

usual. The text of

this aria is “Jesu,

deine Gnadenblicke

kann ich doch

beständig sehen”

(Jesus, Thy look of

mercy I can still

see constantly);

thus the same

configuration fits

here exactly. The

look of mercy of

Jesus enthroned in

heaven comes from

on high ...

This is delightfully

underlined by the

high ‘close harmony’

without a genuine

bass. The character

of this music is

almost Christmassy,

as if we hear (and

see) the angels

themselves making

music.

The Closing

Chorus (No. 9)

is appropriately

symmetrical with the

opening chorus in

its instrumental

splendour; in this

brilliant web, with

the different pairs

of instruments

passing on the motif

to each other, is

embedded the Chorale

of G. W. Sacer

(1697) “Wenn

soll es doch

geschehen / Wenn

kömmt die liebe

Zeit?” (When

shall it happen /

When cometh the

precious time?) The

melody is sung by

the soprano with

long notes,

augmented by the

wind instruments;

underneath the three

usual voices unfold

a polyphonic

imitative movement.

With “Du Tag,

wann wirst du

sein?” (O day!

When willst thou

arrive?) they take

up the instrumental

figuration more and

more, and sing about

their passionate

longing for the day

of Jesus’s return,

which was promised

at the time of the

Ascension.

Thus

in the great

totality of this

work there is a

vivid and passionate

description of the

wondrous event of

the Ascension, which

tradition has handed

down.

“Sie werden euch

in den Bann tun”,

BWV 44

for Exaudi

Sunday, written in

Leipzig for the

21st May 1724 (a

week after the

above Cantata BWV

86).

After the Feast of

the Ascension the

Sunday liturgy

focuses again on the

great sayings of

Jesus from the

Gospel according to

St. John. On “Exaudi”

Sunday one reads in

ch. 15 (v. 26) to

ch. 16 (v. 4) a

discussion between

Jesus and his

disciples, which

contains: When

the Comforter is

come, whom I will

send unto you

from the Father,

even the Spirit of

truth, which

proceedeth from

the Father, he

shall testify of

me: And ye

also shall bear

witness, because

ye have been

with me from the

beginning (...) They

shall put you

out of the

synagogues: yea,

the time cometh,

that

whosoever

killeth you will

think that he

doeth

God

service. And

these things they

will do unto you,

because they

have not known the

Father, nor me.

But these

things have I told

you, that when the

time shall

come, ye may

remember that I

told you of them.

And these

things I said not

unto you at the

beginning,

because I was

with you). (Only

the underlined

text is referred

to in Cantata 44.

Surely no welcome

message for the

Apostles. The poet

of this Cantata

concludes from this

that, above all, the

devout Christian

must always take

sorrow upon himself.

The Antichrist

persecutes him, but

to no avail though,

because he is like a

palm tree. Ever more

weight hangs from

its branches; ever

higher and

straighter grows its

stem. Exactly in

that way the

Christian soul

grows, so that he

withstands his

persecution. The two

chorales also, which

are combined in the

libretto, follow the

same thoughts.

The quotation from

St. John (ch. 16, v.

2) is divided into

two parts by Bach.

Initially, (No.

1, a Duet for

Tenor and Bass

with two oboes,

bassoon and basso

continuo), he only

uses the phrase “Sie

werden euch in den

Bann tun”

(They will

excommunicate you).

The piece in C

minor, a sad key, is

a five-part

composition (three

instrumental and two

vocal parts). In the

three-part

introduction the

oboes present the

main theme, the

tenor and bass enter

one after the other

with the same

material. On “Bann”

there is every time

a long-held

note, which becomes

disssonant (the Bann,

the

excommunication!)

and the line tries

as it were to close

down. Once

again an example of

how the text

inspires Bach’s

method of

composition.

Without a transition

we come upon the

second phrase of the

St. John quotation (No.

2, Four-part tutti

piece for all

the singers and

instrumentalists) “Es

kommt aber die

Zeit, dass, wer

euch tötet, wird

meinen, er tue

Gott einen Dienst

daran” (The

time cometh, that

whosoever killeth

you will think that

he doeth God

service). Over a

continuously busy

instrumental bass

the four singers

scan this

threatening text

homophonically,

imitated by the

instruments to

increase the effect.

The little word “dass”

is emphasized in

isolation, which is

particularly

curious. Then the

text “wer euch

tötet” follows

quite quietly (piano),

and suddenly loud

again (forte)

comes “wird

meinen, er tue

Gott einen Dienst

daran”. Next

the whole section “es

kömmt” (etc.)

is repeated in a

complex polyphony,

with a graphic

chromaticism on “tötet”.

This No. 2 is one of

the most vivid

passages in Bach’s

cantatas.

There follows a

delightful Aria

(No. 3, for

Alto with Oboe and

Basso Continuo): “Christen

müssen auf der

Erden Christi

wahre Jünger sein”

(Christians on earth

must be Christ’s

true disciples), an

addition by the poet

to the main theme.

The true Christian

should be ready to

bear persecution and

discrimination (torment,

excommunication

and suffering)

to the end. A steady

rhythm (the

steadfastness?)

supports the

three-part movement,

which reminds us of

a dance (Chaconne,

Polonaise?). In the

B-part a long-held

note comes again on

“Bann” and “Pein”

– but also once on “selig”

(blessed)!

No. 4 is a Chorale

arrangement

for tenor and basso

continuo – a true

sleight-of-hand,

which one comes

across only in J. S.

Bach. The tenor

proclaims the four

lines of the old

Chorale melody quite

simply; the lines,

however, are

separated from each

other with an

interlude in the

basso continuo,

which repeats the first

Chorale line,

lightly amended

chromatically and

with the respective

closing cadence, seven

times in

various keys.

The text of the

Chorale is by M.

Moller, 1587 – it

fits in particularly

well in this

context.

This old hymn text

allows the poet to

follow it with a

Baroque recitative (No,

5, Secco

Recitative for

Bass). He

brings the

Antichrist, who

seeks in vain to

destroy the

faithful, onto the

stage. (Here comes

the simile of the

palm trees,

mentioned above,

which grow ever

higher through

increasing weight).

The next Aria

(No. 6, for

Soprano and

all the instruments)

glorifies the

loyalty of God. He wacht

von seine Kirche

(keeps watch over

His church). The

aria is very highly

charged and dynamic.

In the B-part a

picture from nature

is brought to the

simile: “Denn

wenn sich gleich

die Wetter türmen

/ So hat doch nach

den Trübsalstürmen

/ die Freudensonne

bald gelacht”

(For when the storms

also build up / yet

after the storms of

sorrow / the sun of

joy has soon shone

brightly). As

expected, Bach

reaches into his

reserve here; the türmen

is vividly portrayed

in the score and

acoustically for our

ears; above a

steadily pulsating

bass note successive

sixth chords climb

upwards; as soon as

the top is reached

the bass itself

becomes fully

chromatic. The voice

also contributes to

the picture, with an

rising set phrase.

The Freudensonne

which “lacht”

is drawn with fast

triplets in the

vocal part,

supported by the

basso continuo. This

combination is

repeated once again

just before the

expected “da capo”.

The Closing Chorale

(No. 7) is by

Paul Fleming (1642):

the 7th verse of the

hymn “In allen

meinem Taten” (In

all my deeds) – “So

sei nun, Seele,

deine / Und traue

dem alleine / Der

dich erschaffen

hat” (So now

be His, my soul, /

and trust none other

/ than He who

created thee). It is

presented simply in

four parts (the tune

is also known as “O

Welt, ich muss

dich lassen” –

O world, I must

leave thee).

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|