|

|

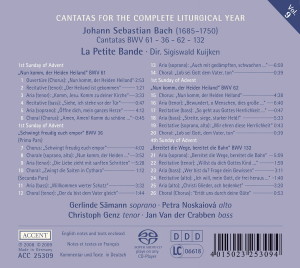

1 CD -

ACC 25309 - (p) 2008

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25309 - (p) 2008 - rectus

|

|

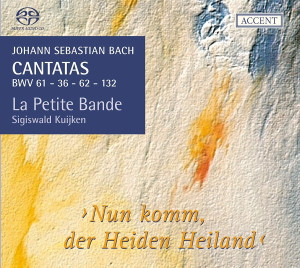

CANTATAS -

Volume 9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| First Sunday of Advent |

|

|

|

"Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland", BWV 61

|

|

13' 40" |

|

| -

Ouvertüre (Chorus): Nun komm,

der Heiden Heiland |

2' 53" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Der

Heiland ist gekommen |

1'

21"

|

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Komm, Jesu,

komm zu deiner Kirche |

3' 33" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Siehe, ich

stehe vor der Tür |

0' 47" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Öffne dich,

mein ganzes Herze |

4' 12" |

|

|

| - Choral

(Chorus): Amen, Amen! Komm du

schöne Freudenkrone |

0' 45" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| First Sunday of Advent |

|

|

|

| "Schwingt

freudig euch empor", BWV 36 |

|

27' 37" |

|

Part

one

|

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Schwingt freudig euch

empor |

4' 02" |

|

|

| -

Choral (soprano, alto): Nun

komm, der Heiden Heiland |

3' 52" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Die Liebe zieht

mit sanften Schritten |

5' 28" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Zwingt die Saiten in Cythara |

1' 12" |

|

|

| Part

two |

|

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Willkommen weter

Schatz! |

3' 32" |

|

|

| -

Choral (tenor): Der du bist

dem Vater gleich |

1' 44" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Auch mit

gedämpften, schwachen Stimmen |

6' 59" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Lob sei Gott dem Vater, ton |

0' 39" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| First Sunday of Advent |

|

|

|

| "Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland", BWV 62 |

|

19' 09" |

|

| -

Chorus: Nun komm, der Heiden

Heiland |

4' 38" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Bewundert, o

Menschen, dies große Geheimnis |

6' 40" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Si eght

aus Gottes Herrlichkeit und Thron |

0' 47" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Streite, siege,

starker Held! |

5' 33" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano, alto):

Wir ehren diese Herrlichkeit |

0' 43" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Lob sei Gott, dem

Vater, ton |

0' 39" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Forth Sundaz of Advent |

|

|

|

| "Bereitet die

Wege, bereitet die Bahn", BWV

132 |

|

16' 13" |

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Bereitet die

Wege, bereitet die Bahn |

5' 09" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Willst

du dich Gottes Kind... |

1' 59" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Wer bist du?

Frage dein Gewissen |

3' 11" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ich will,

mein Gott, dir frei heraus bekennen |

1' 40" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Christi Gleider,

ach bedenket |

3' 20" |

|

|

| -

Choral (Chorus): Ertöt uns

durch deine Güte |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin (leader) |

|

| Christoph

Genz, tenor |

- Katharina

Wulf, violin |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Giulio

D'Alessio, violin |

|

|

- Ann

Cnop, violin,

viola

|

|

|

- Marleen

Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Makoto Akatsu, violoncello

da spalla |

|

|

- Marian

Minnen, basse de violon |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe |

|

|

- Vianciane

Baudhuin, oboe |

|

|

- Marleen

Leichner, cornetto |

|

|

- Mélanie

Flahaut, fagotto |

|

|

- Ewald

Demeyere, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - 11/12 December

2008 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Günter

Appenheimer, Tonstudio Van Geest

(Germany) | Kohei Seguchi |

Eckhard Steiger, Tonstudio Van

Geest (Germany) |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25309 - (1 CD) - durata 76'

39" - (p) 2008 (c) 2009 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

Advent

Cantatas BWV 61,

36, 62 and 132

The season of Advent

includes the four

last weeks before

Christmas: Jesus

Christ “arrives”

(Latin: advenit).

The church year

begins with the four

Advent Sundays as

preparation for the

birth of Christ,

which is celebrated

on the 25th

December.

In the Lutheran

churches in

Leipzig

cantatas were only

performed on the first

Sunday in Advent in

Bach’s time. In

Weimar, however,

there were, in the

years which Bach

spent there, cantata

services on all

four Sundays

in Advent. For the

second, third and

fourth Sundays in

Advent, therefore,

only Weimar

cantatas have come

down to us, among

which those for the

second and third

Sundays have just

the text preserved.

(BWV 70a “Wachet!

Betet!”

(Watch! Pray!) for

the second Sunday in

Advent is a

reconstruction based

on the Leipzig

Cantata for the 26th

Sunday after

Trinity. From it we

know that it, in

turn, is based on

the Weimar Cantata

for the second

Sunday in Advent. We

intend to use this

Leipzig Cantata (BWV

70) for the latter

Sunday.

So, for listeners to

this cycle of

recordings, we have

decided, in spite of

everything and “as a

compromise”, to

include four

cantatas for the

whole Advent season,

three Cantatas from

the first Sunday

in Advent (BWV 61,

62 and 36), together

with the sole

surviving Cantata

for the fourth

Sunday in Advent

(BWV 132). Cantatas

BWV 61 and 132 come

from Weimar, BWV 62

and 36, on the other

hand, are from

Leipzig.

The fact is that

there is a

difficulty for

today’s listener due

to the following

correlation: most

organs in Bach’s

time (including

those in both Weimar

and Leipzig) were

tuned to a pitch

which was about a

semitone higher than

our “official” pitch

today of A=440 Hz.

In Weimar

and many other

places it was usual

that the

instrumentalists and

singers played at

this high pitch of

the organ (A=about

465 Hz). Composers,

therefore, took this

practical aspect

into account with

the notation of

their compositions.

In the process some

wind players have to

transpose their

lowtuned instruments

(mostly oboes in the

French tradition)

correspondingly

higher. They got,

therefore, notes

written higher than

those of their

colleagues, because

they “sounded”

lower. In Leipzig,

however, the

decision had been

taken a couple of

years before Bach’s

employment that the

whole ensemble

(singers and

instrumentalists)

should play a tone

lower, that is to

say, they should

sing and play with

the organ (thus

about A=415 Hz) – in

which the organist

got notes which were

written a tone lower

than his colleagues,

but ‘sounded’ a tone

higher.

This variable pitch

has also been

retained in our

recording. Each

string player,

therefore, plays on

two instruments: on

one tuned higher

(465 Hz) for the two

Weimar Cantatas BWV

61 and 132, and on

one tuned lower (415

Hz) for the two

Leipzig Cantatas BWV

62 and 36. The wind

players also use

instruments which

were usual in Weimar

and Leipzig at the

time.

This results in a

clear distinction

between the

Cantatas, depending

on whether they are

performed in the

Weimar or the

Leipzig manner – the

higher pitch of the

Weimar Cantatas

displaying a rather

more austere and

more archaic

colouring.

“Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland”,

BWV 61

(Now come, thou

Saviour of the

Gentiles), Weimar

1714 (for

the First Sunday

in Advent)

The title on the

autograph is: “Concerto

à 5 Strom. 4 Voci.

Domin: 1 Adventu

Xristi. JSBach”.

The instruments are

“Due Violini, due

Viole, Violoncello

è Fagotto / Sopr.

Alto, Tenore è

Basso /

col’Organo”.

Dated 1714.

The text for the

Cantata is by

Erdmann Neumeister

(1671-1756).

Neumeister is valued

as the creator of

the well-known

cantata form, in

which arias and

recitatives

alternate, as in

Italian chamber

cantatas and in

opera. From 1704 ten

annual cycles of

church cantata texts

by him were

published.

The Opening

movement (no. 1)

of the work (“Nun

komm, der Heiden

Heiland”) is the

first verse of the

well-known hymn “Veni,

Redemptor Gentium”

by St. Ambrose

(Milan, end of the

4th century) in

Luther’s translation

of 1524. This song

is, above all, one

of the best loved

Christmas hymns in

the Lutheran

tradition.

Neumeister retained

Luther’s four-line

verse verbatim, and

continues with his

own poetic work.

In this Cantata Bach

clearly illustrated

the first Sunday in

Advent as the start

of the church year,

by combining this

opening text with

the form of a French

overture. This form

stems from French

theatre music of the

second half of the

seventeenth century,

and displays a

symmetrical

three-part

structure: starting

with a very clearly

scanned part in even

time (thus binary:

vertically crossed

C, or 2, or 2/2 as

the time signature)

in a slower tempo

and a dotted rhythm;

there follows a

faster fugato

section in triple

time, and finally a

return to the first

tempo (frequently

with the same

material as in the

opening section).

Bach, like most

composers throughout

Europe at that time,

had loved and

cultivated this

form, as is shown by

his four well-known

“Orchestral

Suites”.

Presumably he wrote

many more such

suites, but sadly

only these four have

come down to us.

With these

“overtures” it is

usually a question

of purely

instrumental music,

in which the sound

colour comes above

all from the mixture

of strings with

oboes and bassoon

(flutes arrived for

the first time later

in the development

of the overture, for

example with

Telemann and J. Ph.

Rameau). This

“French” sound, and

the compositional

style connected with

it, was in the

Baroque era a basic

element of music in

all the courts of

Europe, and was also

an important

cultural asset of

the international

bourgeoisie.

If Bach, therefore,

used a “French

Overture with

vocal

participation”

as the instrumental

basis for the

beginning of this

Cantata, this gave

rise to familiar

feelings for most

listeners; here was

an expression of

both celebration and

magnificence.

A further reason for

Bach to choose the

overture form here

may have been the

fact that he was

required, as

official

Kapellmeister in

Weimar, to deliver a

church cantata every

month, and this

Cantata was the first

of the series.

The four lines of

the first verse of

Luther’s hymn were

spread out in the

overture as follows:

the first two lines

were set to the

first part of the

overture (Nun

komm, der Heiden

Heiland / Der

Jungfrauen Kind

erkannt – Now

come thou Saviour of

the Gentiles / known

as the Virgin’s

child), the third

line to the faster fugato

middle section (Des

sich wundert

alle Welt – to

the astonishment of

the whole world) and

the last line to the

third, again slower,

part of the overture

(Gott solch

Geburt ihm

bestellt – a

birth so ordered by

God). That Bach very

skilfully, in the one

line (the third),

doesn’t speak of the

exalted and the

Divine but of the

worldly “now”,

brought the verse

alive, with the four

singers doubling the

instruments in the fugato.

Bach used Luther’s

hymn in this opening

chorus, because

every parishioner

knew it, but

nevertheless very

skilfully. The

melody of the first

lines (Nun komm

der Heiden Heiland)

is initially heard

in the instrumental

bass, before it is

sung by each of the

singers individually

(actually in the

sequence Soprano

– Alto – Tenor –

Bass). The

descending sequence

of voices

undoubtedly

illustrates the

“descent” of God to

our world through

the birth of Christ.

Between the alto and

the tenor

performance of this

opening line the

melody is heard once

again in the

instrumental bass.

The second line is

only sung once,

actually

homophonically by

the four voices, to

the known melody.

The fugato

theme of the middle

section is clearly

derived from the

original song melody

on the text “Des

sich wundert

alle Welt”.

This text is

repeated very

frequently, and

thereby illustrates

the crowd of people,

who remain

astonished.

The closing line of

the verse is sung

like the second line

in a simple

homophonic

four-voice setting

to bring the

overture to an end.

After this splendid

movement the

Neumeister texts

begin: a Secco-Recitativo

for tenor (no. 2).

The poet clearly

shows, how God,

through the birth of

Jesus, had accepted

us as being of his

blood, and “allowed

his light to shine

upon us with his

full blessing”. Bach

abandons the secco

character in favour

of an

arioso-dialogue

between the tenor

and the basso

continuo in this

passage, in which

the poet suddenly

turns directly to

God; the intimacy of

contact with God is

illustrated here.

This recitative

leads us to the

following Aria

(No. 3), in

which the tenor,

accompanied by all

the strings, sings “Komm,

Jesu, komm zu

deiner Kirche

– Come, Jesus, come

to Thy church”.

Violins and violas

play in unison. The

movement throughout

is strictly three-part.

(Ought we to assume

that here the whole

Trinity is

meant, God the

Father, Son and Holy

Ghost?) The main

outline of the topic

is predominantly descending

(God comes down from

heaven to us below).

Above all the basso

continuo line

displays this

characteristic time

and again. A simple

festiveness

prevails, which is

already rather

“Christmassy”. In

the B-part (minor

key) of the aria the

poet Neumeister goes

so far as to ask

Jesus “gesunde

Lehre zu erhalten

– to maintain sound

teaching” through

his appearance.

According to A. Dürr

(Die Kantaten von

J. S. Bach, 1971)

this is a clear

allusion to the

emerging Pietism.

No. 4 is a

vivid Accompanied

Recitative for

Bass and

strings. The strings

are plucked instead

of being bowed (pizzicato

is the familiar term

for this method of

playing). The text

comes from the Revelation

of Saint John: “Behold,

behold, I stand at

the door, and

knock: if any man

hear my voice, and

open the door, I

will come in to

him, and will sup

with him, and he

with me”. The

“knocking” can be

heard in the pizzicato,

the repetitions

metrically strict.

The bass (as Vox

Dei, the voice

of God) likewise

declaims the text in

a deliberate way.

How the word “knock”

is treated is

noteworthy!

This recitative

leads us on to No.

5, a short,

touching Aria

for Soprano

with basso continuo

(here it is

specified: Violoncello

– in our version

therefore

violoncello da

spalla – with

organ). The poet

departs from the

Revelation text,

which he has

abbreviated: the

soprano sings: “Öffne

dich, mein ganzes

Herze – Open

thou, my whole

heart”. That this

text is given to a

high voice allows us

to suspect that Bach

connected these

words with the

“annunciation” (the

message of the angel

to Mary, that she

would bear God’s

child), and with

Christmas (the

birth). Mary is

invisibly present

here, in my opinion,

as the greatest

example of the

“opening” of the

hearts of mankind to

the coming of God.

The A-part of the

aria (in a calm

three-four time with

striding quavers) is

dominated by the

rhythmic prosody of

the words “öffne

dich”. The

basso continuo

presents this set

phrase at the

beginning of the

six-bar instrumental

introduction; a

short ascending

line, which with a

rest at the end

stays “open”.

Clearly here the

picture of an “opening

door” is

suggested! For the

B-part the time

changes from three

to four, though with

striding

“andantequavers”.

The soprano here is

independent of the

bass as before, up

to the words “O,

wie selig - O,

how blessed”, where

the bass again comes

to the fore, and the

section ends in a

close dialogue. A

repetition of the

A-part follows (the

so-called da

capo).

This Cantata closes

with an atypical Chorale

(No. 6) “Amen,

Amen! / Komm du

schöne

Freudenkrone,

bleib nicht lange!

/ Deiner wart ich

mit Verlangen

– Amen, Amen! /

Come, thou crown of

joy, delay no

longer! / Thee I

await with longing”.

Erdmann Neumeister

borrowed here the

second half of the

last verse of the

hymn “Wie schön

leuchtet der

Morgenstern –

How beautifully

shines the morning

star” by Ph. Nicolai

(1599). Bach, by

analogy, similarly

used only the second

half of the

corresponding

chorale tune. This

short piece is no

simple movement for

four voices, but a

figured composition

with a contrapuntal

structure and a

festive character.

On the final chord

the violins play a

high g’’’; symbol of

joy at the Coming...

“Schwingt freudig

euch empor”,

BWV 36

(Raise thee up

with joy), Leipzig

1731 (also

for the First

Sunday in Advent)

This Cantata has a

long, interesting

history, and is a

good example of

Bach’s working

methods.

Its source is a secular

feast cantata

from 1725 (with the

same opening text,

BWV 36c) for the

birthday of a

popular teacher, who

cannot be identified

with certainty. Bach

later altered this

composition twice

more for other

“secular” occasions

(BWV 36a “Steigt

freudig in die

Luft – Soar

joyfully in the air”

in Cöthen, 1726, and

BWV 36b “Die

Freude reget sich

– Joy awakens” in

Leipzig, 1735?) and

finally as a church

cantata in

Leipzig, 1725. For

the last the opening

chorus and the three

arias were taken

with suitable texts

from the secular

versions, and only

the closing chorale

was added (actually

the last verse of

the hymn by Ph.

Nicolai of 1599, “Wie

schön leuchtet der

Morgenstern”,

which we have also

come across as the

close of Cantata

61). By 1731 Bach

had given the piece

the shape in which

it is mostly

performed today. To

the earlier 5

movements of the

church cantata of

1725 (numbered

“today” 1, 3, 5, 7

and 4) were added

three new ones

(movements 2, 6 and

8). The Cantata was

divided into two

parts (before and

after the sermon),

and each part closes

with a simple

chorale.

The result is, for

Bach, a unique form

of cantata

composition, in

which there is no

recitative. The same

is also found in the

strict Chorale

Cantatas, where each

verse of the

selected church hymn

is set in a

different

harmonisation. After

the splendid opening

chorus, arias

alternate with

choral

harmonisations –

though with chorale

texts which do not

come from the same

hymn. The (new) 2, 6

and 8 come from the

Lutheran translation

of the old hymn “Veni,

Redemptor Gentium”

by St. Ambrose (see

also Cantatas BWV 61

and 62), and the

closing chorale of

the first part (No.

4) is by Ph.

Nicolai, as noted

above.

The poet of

movements 1-3-5-7

(the movements,

therefore, which

were not

taken from existing

church hymns) is not

known. His style is

very “artificial”,

which, at that time,

was thought to be

positive rather than

negative

(“artificial” meant

“elaborate”

basically). So the

text of the opening

chorus, in

simple words, meant:

Sing to the heavens

with joy – but with

the thought that God

Himself is coming

towards you (this is

clearly the Advent

idea, as contained

in the Lutheran hymn

“Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland”).

The sense of the

text for No. 7

(soprano aria “Auch

mit gedämpften

Stimmen – Also

with muted voices”)

is: one must not

shout at God, in

order to honour Him

– He also hears the

weak voices!

The Baroque word

picture sometimes

almost veils the

direct meaning

through its

elaborate invention.

The Opening

chorus (No. 1)

is pervaded by an

inspired enthusiasm.

In the 13-bar

introduction the two

oboes d’amore and

the first violin

follow soaring lines

(“Schwingt

freudig euch

empor”) with

varied changes from

binary semiquavers

to groups of

triplets. Then the

same main motif is

heard in succession

from the bass,

tenor, alto and

soprano: always with

a rising sweep in

the sequence!

Already this opening

shows, in my

opinion, how this

music was soloistically

envisaged –

madrilesque,

virtuoso. A doubling

of the vocal parts

would only have

darkened what, with

soloists, is so

simple, bright and

clear. With the

B-part (“Doch

haltet ein –

Yet stay”) the flow

correspondingly

falters: the voices

scan vertically and

homophonically in

this section of the

text, while the

instruments continue

as before. Then the

A-text and the

B-text are again

repeated in other

keys, which the

vocalists close with

a jubilant “Es

naht sich selbst

zu euch der Herr

der Herrlichkeit

– The Lord himself

in His Glory

approaches you”). In

the six bars of the

instrumental

postlude the first

violins depict “Es

naht sich der

Herr” with a

last descending

phrase, and “Schwingt

freudig euch

empor, ihr Zungen”

with an ascending

one.

The No. 2

(added in 1731) is

an astonishing threepart

Chorale

Harmonisation

of “Nun komm,

der Heiden

Heiland”. The

librettist used the

first verse of the

well-known church

hymn (see above).

The original melody

for each line of the

verse is treated

contrapuntally by

Bach according to

the relevant words.

The piece is a duet

for soprano and

alto, in which each

voice is doubled by

an oboe d’amore. The

continuo part (organ

and violone) is the

fundamental voice,

which binds together

all the motivic

sections into a

continuous flow. It

is, for a change,

embellished more

richly than the two

upper voices. An

intoxicating

meditative force

comes from this

section. Here the

normal

“expressiveness” of

music no longer

prevails...

There follows an Aria

(No. 3) for tenor

and basso continuo

with obbligato oboe

d’amore (“Die

Liebe zieht mit

sanften Schritten”

– Love lures with

gentle steps). The

clear iambic prosody

of the text

characterises the

dialogue between the

tenor and the oboe.

The tempo recalls an

elegant minuet. The

poet sings of how

the love of God

fills the heart of

man.

As the Closing

Chorale to the

first part of the

Cantata No. 4

follows the sixth

verse of the Nicolai

hymn from 1599, “Wie

schön leuchtet der

Morgenstern”:

“Zwingt die

Saiten in Cythara

– Press hard the

strings in Cythara”)

(in the earlier,

shorter church

version of the

Cantata the seventh

and last verse of

this hymn was used

as the closing

chorale) – the

chorale poet sings

of the Glory of God,

and rejoices in the

Lord.

The Second part

(after the sermon)

begins with an

enthusiastic Basso

aria (No. 5)

with strings and

basso continuo, “Willkommen,

werter Schatz ...

Zieh bei mir ein!

– Welcome, dear

treasure ... draw

near to me!”.

The instrumental

first announcement

of the word “Willkommen”

runs through the

whole piece like a

leitmotif. The

highly-figured first

violin part recalls

the opening movement

of the Cantata. In

love and faith the

heart welcomes the

Lord.

No. 6

follows, likewise a

1731 insertion of a

Chorale

Harmonisation

of the sixth

verse of the

Lutheran “Nun

komm der Heiden

Heiland”: “Der

du bist dem Vater

gleich / Führ

hinaus den Sieg im

Fleisch –

Thou, who art the

father of us all /

lead us to victory

over our flesh” for

tenor, two oboes

d’amore and basso

continuo. The tenor

sings the chorale

melody in slow equal

notes. At the same

time the oboes

d’amore and the

basso continuo

provide a fast,

feverish and

imitative framework

(molt’allegro),

which undoubtedly

portrays the

“eternal power of

God”.

The Aria (No. 7)

for soprano

and basso continuo

with obbligato

violin again

stems from the

original secular

version of the work,

in which the viola

d’amore was

thought of for the

violin part. The

first lines of the

original text are “Auch

mit gedämpften,

schwachen Stimmen

/ Verkündigt man

der Lehrer Preis

– Also with muted,

feeble voices / the

prize of the teacher

is announced”. The

first church version

(1725) was a tone

higher, in A major.

Here Bach returns to

the original key of

G major, and

stipulates the

necessity of a mute

for the violin, so

that the violin

sound is muted and

closer to the

strength of the

viola d’amore’s

sound. Thus the “gedämpften,

schwachen Stimmen”

are in practise

achieved here

musically. In this

aria a very intimate

atmosphere prevails.

The “flowery” violin

part shows us the

gentle exaltation of

the awakened spirit,

which “praises God’s

Majesty”. At the

beginning of the

B-part Bach takes

advantage musically

of the word “schallet

– resounds” by

putting in an “echo

effect”, which

allows us to live

through “schallen”

three-dimensionally.

This aria is one of

the most charming in

all the cantatas of

Bach.

This extended

Cantata closes with

an added simple Chorale

(No. 8) on the

last verse of

the hymn “Nun

komm, der Heiden

Heiland” of

St. Ambrose in

Luther’s version,

from which the two

Chorale

Harmonisations added

in 1731 also come: “Lob

sei Gott dem Vater

ton – Praised

be God, the Father”.

This text

corresponds to the

Latin “Gloria

Patri et Filio et

Spiritui Sancto”

– “Glory be to the

Father, and to the

Son, and to the Holy

Ghost“, with which

today the psalms are

very often ended.

“Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland”,

BWV 62

(Now come, thou

Saviour of the

Gentiles) Leipzig,

1724 (also

for the First

Sunday in Advent)

This Cantata belongs

to the second annual

cycle of the Leipzig

cantatas (as from

Trinity 1724), the

cycle of the

so-called Chorale

Cantatas.

These Chorale

Cantatas are always

based on a particular

church hymn –

not, for instance,

the Gospel or the

Epistle reading for

the appropriate

Sunday. There are

two kinds of this

genre. In the first

the whole hymn text

is simply retained word

for word in

all the verses, in

which each verse is

a through-composed

section and lacks

recitative

completely. In the

second, only the beginning

and the end of the

hymn are

retained, and the

middle verses are

freely shaped into

recitative and aria

by the Baroque poet,

as we know from the

majority of other

cantatas.

Cantata 62 belongs

to the second

category. Of the

eight verses of the

chosen church hymn

(here again the

well-known “Nun

komm, der Heiden

Heiland” by

Luther after the old

hymn “Veni,

Redemptor Gentium”

by St. Ambrose from

c. AD 395) verses 1

and 8 are retained

verbatim, verses 2/3

and 4/5 were

collected by a poet,

who sadly remains

unknown today, and

reworked (Nos. 2 and

3 of the Cantata),

and the sixth and

seventh verses were

shaped in a new form

(Nos. 4 and 5 of the

work).

The Cantata is set

for 2 oboes, strings

and basso continuo,

and a cornett

(Zink), which takes

part in the chorale

melody in the first

and last movements.

The First

Movement (opening

chorus) is a

highly calculated

composition with a

brilliant

concertante

character. The

16-bar introduction

in 6/4 time starts

in the high register

(oboes with violins

and violas in

unison: these

strings represent a

“bassetto”, i.e. a

bass part an octave

higher). In the

third bar the

chorale theme

appears in the basso

continuo, clearly

recognisable by the

long note values. At

the same time the

first violins

separate themselves

from the other

strings and start

figures of scales

and arpeggios, which

last throughout the

piece and lend it a

characteristic

colour. At the end

of the introduction

the chorale theme is

heard again in the

oboes – but this

time twice as fast

as it was in the

bass before (the

Saviour coming

soon?). The singers

enter here: first

the three lower

voices with

imitative entries of

a motif derived from

the chorale theme,

and finally the

soprano (reinforced

by the cornett) with

the original melody

of the first line of

text, which as

before is heard in

the bass with long

notes. On the last

syllable an 8-bar

intermezzo starts,

in which, in the

last two bars, the

opening theme of the

chorale is heard in

the oboes, and in

fact – as at the end

of the introduction

– twice as fast as

in the soprano

previously. There

follows the second

line of the church

hymn in the soprano

(with the cornett,

in long notes as in

the first line),

supported by the

three lower voices

with a free fugato.

After an intermezzo

– this time 7 bars

long – the third

line “des sich

wundert alle Welt

– at which the whole

world marvels”

begins. As in the

Weimar Cantata BWV

61, this line is

also very freely

developed here by

the vocalists, like

the remaining three

lines. The alto,

tenor and bass

declaim in a fast

syllabic prosody,

combined with a

rapid vocalise: “des

sich wundert alle

Welt” – the

picture of

‘marvelling’

together? This

highly imaginative

lay-out is typical

of the Baroque

method of

composition. After a

10-bar intermezzo

(the two last bars

again bring in the

main theme in the

oboes!), the last

line is heard, whose

melody is the same

as for the first

line. The lower

voices again begin

with a fugato

entry derived from

the motifs, and the

chorale melody

appears in the

soprano as before,

reinforced by the

cornett. On the last

syllables the whole

instrumental

introduction is

repeated, as a

postlude. This

movement is

continuously

controlled and

supported by the

instrumental

ensemble, which

presents itself,

really, as a

concerto movement

and a dynamic

background to great

events – a picture

of an always

“active” human

community, which is

soon to receive the

Saviour?

As the second

movement there

follows Tenor

Aria (no. 2),

which, as noted

above, combines the

original chorale

verses 2 and 3 in a

new poem. In an

infectious 3/8 time

the text “Bewundert,

O Menschen, dieses

grosse Geheimnis

– Marvel, O mankind,

at this great

secret” is brought

nearer to the

listener. This da

capo aria, in rondo

form, is

through-composed

with dance-like joy.

The tenor sings,

typically enough,

long vocalises on

the important “höchster

– highest” and “Beherrscher

– Almighty”. This “grosse

Geheimnis”

concerns the coming

birth of Jesus to

the virgin Mary.

A short Secco

Rezitativo (No. 3)

for bass combines

the original verses

4 and 5 of the

Lutheran hymn. Here

the heralded Son of

God is welcomed,

named and praised in

advance as the Hero

from Judaea.

Melismas on “laufen

– hasten” and “heller Glanz

– bright splendour”

decorate this

recitative.

The following Aria

(No. 4) for Bass

and strings

‘all’unisono’,

“Streite, siege,

starker Held! /

Sei für uns im

Fleische kräftig

– Strive, conquer,

bold Hero! / Be

strong for us in Thy

Incarnation” is

based on the new

working of the

original verse 6.

The united strings

symbolise, as it

were, the power of a

triumphant army. The

whole aria is a

straightforward

twopart web. The

vocal soloist on the

one hand and the

strings with organ

on the other are in

competition. As we

on occasion hear the

Vox Dei

assigned to a bass,

so now we “hear” the

Power of God

at work, in the form

of the bass.

There now follows a

modified repetition

of the original

verse 7 (Accompanied

Recitative for

soprano and alto,

with strings, No.

5). The text

describes the coming

journey to the

manger, where Jesus

is going to be born.

The faithful unite

in their worship

(soprano and alto

sing in absolutely

identical prosody!).

This Cantata for the

first Sunday in

Advent also closes

with the last verse

of the hymn “Nun

komm, der Heiden

Heiland” (No.

6 “Lob sei

Gott – Praised

be God”) – of the

exact text, which

also closes Cantata

36: the doxology Gloria

Patri et Filio et

Spiritui Sancto,

which Luther put

into German.

“Bereitet die

Wege, bereitet die

Bahn!, BWV 132

(Prepare ye the

way, prepare ye

the highway!) Weimar,

1715 (for

the fourth Sunday

in Advent)

This work is the

only surviving Bach

cantata for the

fourth Sunday in

Advent. The

autograph says: “Domenica

4 Adventu Xristi /

Concerto /

Bereitet die Wege,

bereitet die Bahn

/ à 9 / 1 Hautbois

/ 2 Violoni /

1 Viola /

Violoncello / S.

A. T. è B / col

Basso per l’Organo

/ di GS Bach /

1715.” In the

score, however, bassoon

and violone are also

mentioned next to

the named

instruments of the

title page.

(Incidentally the

Italian signature “di

G(iovanni)

S(ebastiano)

Bach” is

noteworthy. The

Italian predominance

in the music of that

time is indeed

obvious).

This Cantata comes

from Weimar, and is

clearly

characteristic of

the situation there

with regard to

pitch. The “Hautbois

– oboe” part is a

minor third higher

than the other

parts. The “Hautbois”

was introduced into

Germany by the

French oboists, who

had to flee from the

homeland on account

of their Protestant

religion. The normal

French pitch was

actually a minor

third lower than the

high choir pitch of

the organ in the

North.

The text of the

Cantata is by

Salomon Franck, the

famous Weimar

cantata poet. In

1715 there appeared

a collection by him,

“Evangelisches

Andachts-Opffer”,

which contains this

Cantata. Salomon

Franck turned his

attention to the

Gospel lecture for

the fourth Sunday in

Advent: the evidence

of John the Baptist.

The lecture also

contains the

paraphrase from the

Old Testament of

Isaiah 40: “Bereitet

die Wege –

Prepare ye the way”.

The piece starts

with a very virtuoso

Soprano Aria (No.

1) with oboe,

strings, bassoon and

basso continuo. The

“Prepare ye the way”

is suggested

musically by the

frequently repeated

entry of the main

motif. The soprano

has to sing a really

very long and

difficult vocalise

on the word “Bahn

– highway”, which

cannot indicate

anything other than

the long road which

the Christian must

travel in Imitation

of Christ. The oboe

part forms, as it

were, the main duet

with the soprano,

which often

illustrates the “Bereiten

– prepare” and “Nachfolgen

– imitate”. Three

times in the course

of the piece the

unaccompanied

soprano cries out,

as an inspired

herald: “The Messiah

comes!”

In the Secco Recitativo

(No. 2) for

tenor the appeal,

from Isaiah, to the

individual Christian

is referred to: “Willst

du dich Gottes

Kind und Christi

Bruder nennen

– Wouldst thou call

thyself a child of

God and a brother of

Christ”. In this

long recitative free

“secco” fragments

alternate with

measured “arioso”

phrases, where

singer and

instrumental bass

play together on the

same level as a

duet. On the words “Wälze

ab die schweren

Sündensteine –

Roll away from the

heavy rocks of sin”

Bach writes in both

parts a curved

melodic line, which

clearly illustrates

the “rolling away”.

There follows an

ostinato Bass

Aria (No. 3)

with obbligato

violoncello (“da

spalla” with us) and

basso continuo

(organ and 8’

violone). The

keystone of the

composition is the

continually repeated

rhythmic form, which

corresponds to the

syllables of the

phrase “Wer bist

du? - Who art

thou?”. The poet

takes this question

(in the Gospel: the

Jews’ question to

John) as a

leitmotif, in order

to force on the

listeners the

selfsame question.

Admittedly in the

B-part of the aria

he even allows a

negative judgment: “ein

Kind des Zorns in

Satan’s Netze

– a child of evil in

Satan’s meshes”. For

the section “Kind

des Zorns”

Bach uses a harsh

chromaticism. That

this aria is

allotted to the bass

is again clearly

meant to show that

the listener

recognises, in the

bass, the voice of

God (Vox Dei)

and fears it.

In the following Accompanied

Recitative for

Alto (No. 4)

the hypocritical

soul repents, so

that he, who “has

broken the

covenant”, may beg

God for His mercy

and His help. On the

important words and

ideas of the text

Bach skilfully

writes appropriate

dissonances.

The alto follows his

words with a short Aria

(no. 5) with a

solo violin and

basso continuo. The

poet reminds the

listener of what

gifts of Christ were

given through

baptism in the “Christi

Blut- und

Wasserquelle –

Christ’s source of

blood and water”:

they are given “zum

neuen Kleide rotes

Purpur, weisse

Seide – new

clothes of purple,

white silk”. The

alto part, simply

set against the

running figures of

the violin, must

surely portray the

rustling clothes

(and even the

rushing waters of

the source) – in

each case,

therefore, the gift

of God.

In the printed

edition of this

Cantata text by

Salomon Franck the

work closes with a chorale

verse (No. 6)

by Elisabeth

Creutziger (Weimar

1513). In Bach’s

score, however,

there is no longer a

closing chorale (any

more?). Very

probably the last

page of the

manuscript has gone

missing. Presumably

it was a loose page

of paper as the last

page of the

surviving manuscript

is fully written.

The same chorale

text was used by

Bach as the closing

chorale in another

Cantata (BWV 164, “Ihr,

die ihr euch von

Christo nennet

– Thou, who the name

of Christ hath

taken”, 1716). We

have, therefore,

also used this

untransposed version

as a closing chorale

for BWV 132 (as is

usual today). This

does not assume that

Bach would have

ended this Cantata

with an aria which

has a pronounced

chamber music

quality like the

previous piece (No.

5).

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|