|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25308 - (p) 2008

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25308 - (p) 2008 - rectus

|

|

CANTATAS -

Volume 8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

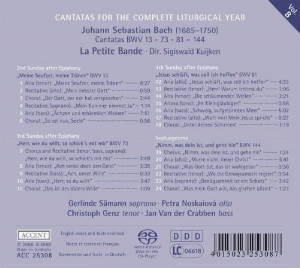

| Second Sunday after

Epiphany |

|

|

|

"Mein Seufzer,

meine Tränen", BWV 13

|

|

22' 11" |

|

-

Aria (tenor): Meine Seufzer,

meine Tränen

|

8' 27" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Mein

liebster Gott lässt mich annoch |

0'

59"

|

|

|

| -

Choral: Der Gott, der mir hat

versprochen |

2' 44" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano): Mein

Kummer nimmet zu |

1' 14" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Ächzen und

erbärmlich Weinen |

7' 51" |

|

|

| - Choral:

So sei nun, Seele, deine |

0' 56" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Third Sunday after

Epiphany |

|

|

|

| "Herr,

wie du willt, so schick's mit

mir", BWV 73 |

|

12' 52" |

|

| -

Chorus & Recitative

(tenor, bass, soprano): Herr, wie du

willt, so schick's mit mir |

3' 48" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Ach senke doch

den Geist der Freuden |

3' 35" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Ach, unser

Wille bleibt verkehrt |

0' 33" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Herr, so du

willt |

3' 47" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Das ist des Vaters Wille |

1' 09" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Forth Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Jesus schläft,

was soll ich hoffen", BWV 81 |

|

16' 46" |

|

| -

Aria (alto): Jesus schläft,

was soll ich hoffen |

4' 33" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Herr!

Warum trittest du so ferne? |

1' 06" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Die schäumenden

Wellen von Belials Bächen |

3' 21" |

|

|

| -

Arioso (bass): Ihr

Kleingläubigen, warum seid ihr so

furchtsam? |

0' 58" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Schweig,

aufgetürmtes Meer! |

5' 02" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Wohl mir!

Mein Jesus spricht ein Wort |

0' 27" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Unter deinen Schirmen |

1' 19" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Septuagesimæ |

|

|

|

| "Nimm, was dein

ist, und gehe hin", BWV 144 |

|

13' 12" |

|

| -

Chorus: Nimm, was dein ist,

und gehe hin |

1' 34" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Murre nicht,

lieber Christ |

5' 41" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Was Gott tut, das ist

wohlgetan |

0' 58" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Who die

Genügsamkeit regiert |

0' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Genügsamkeit

ist ein Schatz in diesem Leben |

2' 42" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Was mein Gott will,

das g'scheh allzeit |

1' 23" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin (leader) |

|

| Christoph

Genz, tenor |

- Jim

Kim, violin |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Makoto

Akatsu, violin |

|

|

- Katharina

Wulf, violin |

|

|

- Mika

Akiha, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe |

|

|

- Koen

Dieltiens, recorder

I |

|

|

- Frank

Theuns, recorder

II |

|

|

- Henry

Moderlak, tromba

da tirarsi |

|

|

- Benjamin

Alard, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - February 2008 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25308 - (1 CD) - durata 65'

01" - (p) 2008 (c) 2009 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

Cantatas

BWV 13 – 73 – 81 –

144

The Cantatas BWV 13

– 73 – 81 – 144 were

written for the second,

third, fourth

and fifth

Sundays after

Epiphany (the

fifth is also known

as Septuagesima).

The Cantatas 73, 81

and 144 were

composed for three

succeeding Sundays

in Leipzig (at the

end of January and

the beginning of

February 1724), and

Cantata 13, on the

other hand, appeared

two years later.

“Meine Seufzer,

meine Tränen”, BWV

13

for the second

Sunday after

Epiphany (the 20th

January 1726).

Bach’s autograph of

this Cantata bears

the title Concerto

da Chiesa.

This reminds us how

Bach himself

specifically liked

to associate his

cantatas with the

Italian concertante

style.

The text is by Georg

Chr. Lehms, who was

the court poet in

Darmstadt between

1710 and 1717. Lehms

wrote four years of

cantata texts, of

which Bach set a

good dozen from the

first year (Gottgefälliges

Kirchen-Opffer,

1711). Lehms’s

style, typical of

the Baroque, is

‘artificial’. He

combined themes from

the obligatory

church lessons with

sought after

illustrative

language.

The poet has only

retained certain

‘echos’ from the

lessons for the

Second Sunday after

Epiphany (the

Epistle to the

Romans 12, 6 and the

story of the

Marriage at Cana

from John). Jesus’s

remark to Mary in

the Gospel according

to St. John, “my

hour is not yet

come”, was

directed at the

disciples, who at

first waited in vain

but finally had full

confidence in God’s

help. At the same

time, a portrait of

the wine and

waterpot from

the wedding at Cana

was also used (cup

of grief, wormwood

juice, wine of joy).

Bach has interposed

the two chorales

(nos. 3 and 6 in the

Cantata, texts from

1626 and 1646).

The Cantata is

divided into two

parts, the first

dealing with the

painful waiting and

imploring, the

second (from the

middle of no. 4, “Doch,

Seele, nein” –

“Yet no, o soul”)

with confidence in

trust in God.

The first movement

is a wonderfully

emotional tenor

aria (“Meine

Seufzer, meine

Klagen” – “My

sighs, my tears”)

with two recorders,

oboe da caccia and

basso continuo. The

key of D minor is

very appropriate for

this Lamento.

Both recorders

support each other

almost continually;

the oboe da caccia

is used rather as a

violin part set

against the solo

singer. It has

frequent long

melismas, and as

such is nearly the

most important

soloist. The opening

motif of the singer,

introduced by the

two recorders,

illustrates the

sighing and weeping,

while the oboe da

caccia immediately

takes on its

individual solo

role. In the second

part, the repeated

motifs on “täglich

Wehmut”

(“daily melancholy”)

and “Jammer”

(“grief”) are

particularly

expressive. The

descending line for

the tenor on “Weg

zum Tode”

(“way to death”),

and the chromaticism

for the recorders on

“So muss uns

diese Pein”

(“so must this pain

for us”) should also

be noted.

There follows a secco-recitativo

for alto

(“Mein liebster

Gott” – “My

dearest God”), which

is very lyrical in

colour. The closing

‘a tempo’ on “flehen”

(“implore”)

illustrates for us,

through widely

jumping intervals,

the futile search in

all directions: God

is nowhere to be

found...

The alto goes

further in a figured

Chorale with

string

accompaniment (no.

3). The

Chorale is doubled

by the wind

instruments and sung

quite simply; each

verse is separate.

The text, by Joh.

Heermann (1626),

insinuates how God

(almost with

‘malicious

pleasure’) withdraws

His trust from the

faithful. A cheerful

gavotte-like dance

music can actually

be heard in the

strings. God enjoys

Himself without

pity, while mankind

seeks Him hopelessly

and in vain. This mise

en scène is

almost unbearable,

the contrast being

shown incredibly

sharply; one almost

thinks of a ‘dance

of death’ from

earlier times.

Afterwards, the

soprano takes on the

lament for the loss

of trust in the secco

recitativo (no. 4).

“Mein Jammerkrug

ist ganz mit

Tränen angefüllet”

(“My cup of grief is

completely filled

with tears”), wrote

Lehms. And then at

last comes the

longed-for turning

point: Enough now, o

my soul, remember

that God can change

lamentation into

joy...

Though someone who

now hopes for a

joyful aria will be

disappointed. In the

Aria (no. 5)

pain and lamentation

is still

(tremendously

urgently) portrayed

– and only in order

to explain how even

this cannot help “der

Sorgen Krankheit”

(“the disease of

sorrow”). The bass

portrays “Ächzen

und erbärmlich

Weinen”

(“Groaning and

pitifully weeping”)

with impassioned

intervals; an

instrumental descant

with a strange sound

(both recorders in

unison doubled by a

solo violin)

combines with the

solo voice after a

long introduction.

The second part of

the text again takes

up the positive

outlook which comes

from trust in God.

There appears “ein

Freudenlicht in

der Trauerbrust”

(“a light of joy in

a heart of sorrow”),

in which plaintive

intervals give way

to more peaceful

lines, but with an

unaltered basic

tempo in the basso

continuo – the

picture of changes

in destiny,

presented on the

ever unchanging

course of time.

Through the

repetition of the

first part of the

text the listener is

directed back to the

earthly vale of

tears.

The Cantata ends

with a simple

four-part Chorale

(no. 6) (text

by Paul Fleming,

1646) on a very

wellknown melody, in

which we are

summoned to be

tolerant and to

trust in God’s

counsel.

“Herr, wie du

willt, so schick’s

mit mir”,

BWV 73

for the third

Sunday after

Epiphany (Leipzig,

23rd January 1724

– thus in the

first year of

Bach’s appointment

as Thomaskantor).

The lessons for this

day are, on the one

hand, another

instalment from the

Epistle to the

Romans ch. 12, 17-21

with further rules

of life, and, on the

other hand, from the

Gospel according to

St. Matthew ch. 8,

1-13.

This passage from

St. Matthew tells of

great multitudes

following Jesus when

he came down from

the mountain. There

came to him a leper,

who had heard the

Sermon, and he knelt

down before Jesus

and said: “Wenn

du willst, Herr,

kannst du mich

reinigen”

(Lord, if thou wilt,

thou canst make me

clean”), whereupon

Jesus put forth his

hand, saying “Ich

will, werde rein!”

(“I will; be thou

clean”).

Immediately, his

leprosy was

cleansed. After

this, a centurion

(an important rank

in the Roman army)

from Capernaum came

to him and begged

him to heal his sick

servant, who lieth

at home. Jesus said

he would come and

heal him, to which

the centurion

answered gratefully

“Herr, ich bin

nicht würdig dass

du zu mir kommst –

aber sprich nur

ein einziges Wort

und mein Knecht

wird genesen sein”

(“Lord, I am not

worthy that Thou

shouldest come under

my roof: but speak

the word only, and

my servant shall be

healed”). Jesus

praised the great

faith of the

centurion and said

to him “gehe,

wie du geglaubt

hast” (“Go thy

way; and as thou

hast believed”) –

and his servant was

healed in the

selfsame hour.

The anonymous poet

took his material

from this Gospel

story. Both stories

had a strong effect

on the minds of the

people, for it

illustrated the

mystery of faith in

a vividly didactic

way. Here the poet

surprises us by not

speaking in the

expected

‘proverbial’ way

(recovery from

illness through

faith), but

symbolically aims at

the faith in Jesus

and the omnipotence

and goodness of God

as the “Weg zur

Genesung”

(“path to recovery”)

of our “geistigen

Krankheit”

(“spiritual

sickness”) in the

hour of our death,

as A. Dürr so

strikingly puts it.

Bach’s setting is

very close to the

poem and uses its

structure. The text

of the Opening

Chorus (no. 1)

is a typical

‘collage’. The first

verse of Kaspar

Bienemann’s Chorale

“Herr, wie du

willt” (“Lord,

as Thou wilt”) (from

1582) is interrupted

three times by the

Baroque author with

pathetic pleas and

cries, which the old

verses bind into the

whole as if under a

dome. Bach ‘helps’

this idea by

allowing the

instruments to build

up a strong unified

web with the vocal

parts. The

instrumental opening

immediately shows us

the oboe motif,

which is present

throughout the piece

(here again the dome

idea!), and

characteristically

is always

accompanied by the

upper strings. The

basso continuo only

appears when the

trumpet (here the

slide trumpet)

suddenly projects

the four opening

syllables (“Herr,

wie du willt”)

of the old chorale

melody as a signal.

After three such

individual signals,

the trumpet finally

plays the whole

first phrase of the

melody. Here also

the full vocal

ensemble enters at

last, rather simply,

with the first two

lines of the chorale

in four-part

harmony. The trumpet

reinforces the

soprano line. An

intermezzo by the

oboes, lasting a bar

and a half,

separates the first

two lines. The

intermezzo also

serves, after the

second line, as a

transition to the

first recitative ‘commentary’

(here from the

tenor). Abruptly, we

are thrown, through

an unexpected

modulation, into the

‘new’, Baroque lines

(“Ach! aber ach!”

– “Ah! woe is me!”);

but the recitative

is only a

mock-recitative,

because the oboes

and trumpet (with

the upper strings)

meanwhile go on with

their rhythmical

contributions, and

so suggest to us

time and again “Herr,

wie du willt”

without saying a

word. With

insertions from the

instruments a free

declamation is not

possible.

After the tenor has

finished his

declaration, we

come, through an

instrumental

transition (again

with the beginning

of the chorale

melody!), to the

third and fourth

lines of the old

chorale, which once

more – with the

involvement of the

strings and trumpet

– are sung in

four-part harmony.

After that, there

follows again the

oboe intermezzo and

the wordless signal

“Herr, wie du

willt”, which

leads though to the

second solo

commentary (bass).

This time we land

more gently on the

next new-Baroque

text (“Du bist

mein Helfer” –

“Thou art my

helper”), in which

the content is also

more sensitive. This

‘bass’ declamation –

like the tenor’s

before – is

meanwhile combined

with the familiar

instrumental motifs.

Bach retains the

alternating

structure; lines

five and six of the

old chorale now

follow, presented in

homophonic four-part

harmony. With a

slight

‘displacement’ we

are then led to the

last new-Baroque

section of the text.

The soprano notes

how often we wrongly

understand God’s

deeds and blessings

as curses and

punishment, instead

of recognising the

eternal healing

power of God’s will.

In addition, this

declaration is

accompanied by the

oboe motifs, and the

signals for “Herr,

wie du willt”

by the trumpet and

the high strings.

And in case we have

still not understood

these signals

correctly, we get

them three times –

this time with text

– sung in four-part

homophonic harmony

(also played by the

instruments as

before). Bach cannot

leave it here, but

with the sudden

appear ance of a

dissonance on the

very last “willt”

(which is only

resolved by the

instruments later)

reminds us that

God’s will is

sometimes

incomprehensible –

or apparently false

– to us; in

cauda venenum

– the sting is in

the tail – thus we

can understand the

technique used here

by Bach.

After this very

special opening

chorus there comes a

Tenor Aria (no.

2) “Ach,

senke doch den

Geist der Freuden

herzen ein!”

(“Ah, pour then Thy

spirit of joy into

my heart”) with

obbligato oboe and

basso continuo. The

piece is built on

the deliberate

combination of

descending (“Ach,

senke doch”)

and rising lines

(which indicate Freude

well).

Throughout there is

a very lively

counterpoint. In the

first part of the

text both the upper

voices (oboe and

tenor) interact with

each other in a

concertante fashion

and are accompanied

by a functional

basso continuo,

which directly

depicts the rising

line and is repeated

from time to time in

the course of the

aria. In the second

part, however, the

basso continuo is on

equal terms with the

oboe and the tenor.

It repeatedly takes

on – alternately

with the tenor and

the oboe – the

descending motif

from the first part

(on “senke doch”

there), in which the

motif is used in the

context of the wavering

joy from

“spiritual

sickness”. The joy

here becomes sick

and feeble, and thus

“descends”. At the

same time Bach

illustrates the wanken

(to waver) and the zagen

(to be timid) with

chromatic

syncopations for the

tenor over a steady

bass rhythm. One can

only be astonished

at how Bach time and

again takes his

formal elements from

the text, and never

becomes lost in

fragmented, dry

‘instructions’.

There follows a

short secco

recitativo (no. 3)

for bass, which

leads directly into

the Bass Aria

(no. 4) with

strings. The secco

portrays mankind,

which never wishes

to think of death.

The Christian,

however, “in

Gott gelehrt,

lernt sich in

Gottes Willen

senken und sagt: Herr,

so du willt”

(“who knows about

God, learns to bow

before God’s will,

and says: Lord,

as Thou wilt”).

These words both

begin the aria and

are repeated sixteen

times by the singer

during the course of

the piece, and

actually are clearly

declaimed like a

passacaglia rhythm

on a steady bass. To

‘answer’ this

‘passacaglia motif’,

“Herr, so du willt”,

Bach time and again

uses a faster

downward motif in

the strings. Perhaps

the calm, obedient

reverence of

Christians before

God’s will? It

sounds roughly like

that to us. As a

third element (the

third building block

of the whole), Bach

uses the rhythm of

the opening

syllables, “Herr,

wie du willt”,

repeatedly in the

strings, but now in

double time, with a

large interval jump

(occasionally an

octave), followed by

two repeated notes.

Because of that this

motif almost works

as a signal

throughout the whole

aria. On the words “Todesschmerzen”

(“pains of death”)

and “Seufzer”

(“sighs”) the

strings also involve

themselves in the

repeated sighing

figures of the

singer. On the words

“so lege meine

Glieder in Staub

und Asche”

(“so lay my limbs in

dust and ashes”) the

key (we had just

arrived in D major)

slides rapidly

towards the minor

key. With the text “so

schlägt, ihr

Leichenglocken”

(“so tolls thy death

knell”) a mournful

pizzicato suddenly

rings out from all

the strings. The

death knell... Under

the last repetition

in the text of the “Herr,

so du willt”

the faster

semiquaver motif in

the strings finally

rings out one time

in an upward instead

of a downward

direction, as if it

now wishes to devote

itself to the will

of God on high.

As a conclusion (no.

5) there is

sung simply a verse

(the last) from the

Chorale “Von

Gott will ich

nicht lassen”

(“From God I never

wish to depart”) by

Ludwig Helmbold

(1563); the text is

a fitting summary of

the basic idea of

the Cantata.

“Jesus

schläft, was

soll ich

hoffen”, BWV 81

for the fourth

Sunday after

Epiphany, 30th

January 1724.

The lesson for

this Sunday is

from the Gospel

according to St.

Matthew 8, 23-27.

Jesus enters into

a ship with many

of his disciples

to cross the sea.

A great tempest

arises. Jesus is

asleep and does

not even wake up.

The disciples were

fearful and awoke

him. He must save

them, but He says

to them: “Ihr

Kleingläubigen,

warum

seid ihr so

furchtsam?”

(“O ye of little

faith, why are ye

fearful?”). Then

He arose and

rebuked the winds

and the sea, and

there was a great

calm.

This legendary

picture of Jesus’s

divine power

inspired the

(anonymous) author

to write his poem.

In Baroque

theatrical style

he devises a

symmetrical plot

around this heroic

theme. In the

first episode

(nos. 1 to 3) it

takes place in the

absence of

the hero; in the

second (nos. 5 to

7) it develops in

his presence.

Between the two

episodes he quotes

verbatim the key

words in the

Gospel story: “Ihr

Kleingläubigen”

(“Ye of little

faith”) (no. 4).

A lamento-like Alto

Aria (no. 1)

“Jesus schläft,

was soll ich

hoffen”

(“Jesus sleeps,

what should I

hope”) opens this

Cantata. The mood

is dejected,

lonely as the poet

sees the abyss of

death open up

before him. The

music illustrates

the sleep,

but at the same

time sadness

and helplessness.

Two recorders

double both violin

parts an octave

higher almost

throughout the

piece; though in

one place they go

their own way. The

tone of the

recorder is often

connected with

pain and sadness,

loneliness and

sorrow (see, for

example, the tenor

arioso in the St.

Matthew Passion: “O

Schmerz! Hier

zittert das

gequälte Herz”

(O pain! Here

trembles the

suffering heart”).

Small fragments of

the motif with

narrow intervals

and long held

notes for the

voice (on “schläft”

– “sleeps”, and “offen”

– “opens”)

emphasise the

melancholy

atmosphere; the

combined sound of

quiet strings and

recorders is

extremely

effective. A few

times the long

motionless notes

are played by the

instruments

(recorders or

strings). As was

to be expected,

the concept is

appropriately

illustrated in the

music, for example

“Todes Abgrund”

(“the abyss of

death”) with

descending and “hoffen”

(“hope”) with

ascending lines.

The following secco

recitativo for

tenor (no. 2)

is a passionate

complaint and

question (“Herr,

warum trittest

du so ferne?”

– “Lord, why goest

Thou so far

away?”). The

devoted listener

can note how every

word, every phrase

receives its own

typical

expression. It is

remarkable, for

example, how the

section “...den

rechten Weg zu

reisen”

(“the correct road

to travel”)

suddenly brings

repose in the

middle of this

expressive stress,

after which, with

the cry “Ach,

leite mich”

(“Ah, lead me”),

it becomes

dramatic again.

The tenor

adds to this with

a stormy Aria

(no. 3). The

text starts in the

first two lines in

dactylic rhythm;

strictly speaking,

in the amphibrach

metric foot –

short-long-short

– which with

constant

repetition is

similar to the

dactylic long-short-short

– “schäumenden

Wellen

von Belials

Bächen”

(“foaming waves of

Belail’s brook”).

The next two lines

become iambic

(short-long),

where a moral

reflection

interrupts the

description of the

raging waves: “Ein

Christ

soll zwar

wie Felsen

stehen”

(“a Christian

should really

stand like a

rock”). The last

two lines follow

again in the same

rhythm as the

first: “Doch suchet

die stürmende

Flut”

(“but seeks the

raging flood”).

Bach has portrayed

the foaming waves

by letting the

first violins play

rapid rising and

descending lines

continually, while

the lower strings

perform a

wave-like

movement. At

certain points

this suddenly

falters, but

equally suddenly

starts again. This

rapid violin line

anticipates the

vocal part, which

follows it for the

first time on the

word “verdoppeln”

(“redouble”) [at

this point

the velocity

actually doubles

from semiquavers to

demisemiquavers!].

Now comes the

central turning

point of the work

with no. 4 (Arioso

for bass and

basso continuo). As

already mentioned,

the poet here places

verbatim the

quotation from St.

Matthew 8, 26 in the

middle of his text.

At this point, as

Jesus reproaches his

frightened disciples:

“Ihr

Kleingläubigen,

warum seid ihr so

furchtsam” (“O

ye of little faith,

why are ye fearful”)

the bass embodies

the voice of God

(Vox Dei). This

section is composed

as a straight duet

for two bass parts,

one vocal and one

instrumental. It is

a constant ‘one

after the other’

imitation, in which

the listener

receives an

‘earbashing’ Kleingläubigkeit

five times and Furchsamkeit

ten times.

The voice of God

goes further in the

next Aria (no.

5) for bass

with all the

instruments, and

orders – in the

words of the poet –

the aufgetürmten

Meer (mounting

sea) to schweigen

(calm) and der Sturm

und Wind

(storm and wind) to

verstummen (be

silent). Here again

the words yield a

mass of

possibilities for

tone-painting, and

Bach hardly misses a

single one: so, for

example, the rising

line on “aufgetürmtes

Meer”; the

deep, long-held note

on “Meer”;

the short, isolated

and imperious “Schweig,

schweig; the “Verstumme”

(frequently followed

by a pause in the

voice); also the

rising line for “auserwähltes”

(chosen) child (to

Heaven); the

chromaticism at the

close of the second

part on “kein

Unfall je

verletzet”

(“shall never suffer

disaster”). Here the

score is almost a

picture, a painting

for those who can

read it correctly!

A short secco Recitativo

(no. 6) for Alto

and basso continuo

describes, so to

speak, the reaction

of the faithful (the

previous

unbelievers?), who

know that they are

saved when Jesus

speaks: “Wohl mir”

(“How happy I am”).

Note how Bach uses

the enharmonic

change between “Sturm”

(a b flat as the

seventh of c) and “aller

Kummer fort” (b flat

is a sharp, the

tritone of e). In

this way he

modulates cleverly

from C major (“der

Wellen Sturm”)

to b minor, thus

down a semitone:

calming down after

the extravagant (“aller

Kummer fort”)!

This Cantata comes

to a close with a

simple fourpart Chorale

(no. 7), the

second verse of the

song “Jesu meine

Freude” by

Johann Franck

(1653). “Unter

deinem Schirmen /

Bin ich vor den

Stürmen / Aller

Feinde frei”

(Under thy

protection / I am in

the storm / free

from all my enemies)

– well-known to all

Bach lovers from the

Motet “Jesu,

meine Freude”

(“Jesus, my joy”),

though this verse is

set as a five-part

movement there.

“Nimm, was dein

ist, und gehehin”,

BWV 144

This Cantata for

Septuagesima Sunday

was written by Bach

for the 6th February

1724 – thus a week

after Cantata BWV

81, two weeks after

BWV 73.

Why the authenticity

of this Cantata is

doubted by a few

academics is

incomprehensible to

me; Bach’s autograph

score has come down

to us, as well as

several ‘close’

copies.

Stylistically there

can also be no

possible doubt, even

if this Cantata has

no impressive

structure.

Bach himself called

this Cantata “Concerto”,

as is the case with

many other cantatas.

The Gospel lesson

for this

Septuagesima Sunday

is from St. Matthew

20, 1-16, the

controversial Parable

of the labourer of

the eleventh hour,

where it is made

clear how it is in

the Kingdom of

Heaven (and whether

we will go

there...?). Each

receives his due –

however not

according to human

judgement, but

according to divine

purpose, which often

conflicts with our

feelings.

The work begins with

a typical four-part

Motet movement

(no. 1) in the

old polyphonic

style, on the key

phrase of the St.

Matthew passage

“Nimm, was dein ist,

und gehe hin” (Take,

that thine is, and

go thy way”), taken

verbatim by the

(unknown) poet. The

declamation of these

words is respected

in the simplest and

clearest way in

Bach’s composition,

so that this

movement ‘reaches’

the listeners very

directly and with

the vividness

necessary for the

sermon.

The main motif

permeates the entire

text and has an

almost imperious

character. As a

direct counter-motif

Bach uses a

repetitive

combination of the

syllables “gehe

hin” (“go thy

way”) in the fast

tempo (through this

it has an almost

descriptive

function: the

“going” takes place,

so to speak, in

front of our eyes).

In another place he

also uses longer

note values for

these three

syllables, which

gives a calmer

horizontal

polyphony, and

produces rather the

endless ‘width’ and

third dimension for

us, in which we can

and must ‘go our

way’.

This brilliant Motet

movement is followed

by an Aria (no.

2) for alto

and strings, “Murre

nicht, lieber

Christ” (“Do

not grumble, dear

Christian”). The

author of the text

takes his subject

from the First

Epistle of St. Paul

to the Corinthians

9, 24 to 10, 5.

Moreover it is very

close to the Gospel

lesson for the day:

the labourer from

the early hour

complains when the

master pays the

labourer from the

eleventh hour the

same amount. Bach

has given the text

an almost dance-like

sound (the minuet is

not far away) – the

picture of a

definite ‘worldly’,

‘human’ reaction to

God’s requirement?

The ‘complaint’

itself is even

clarified for us by

the repeated quavers

in the bass.

What follows is

noteworthy: the main

four-bar motif on

the words “murre

nicht” is

occasionally used in

exact reverse order

(as in a mirror).

Undoubtedly Bach

also wants to feign

here the ‘reverse’

understanding (the ‘non-complaint’)

by way of contrast.

There follows a

simple Chorale

(no. 3) from a

song by Samuel

Rodigast (1674), “Was

Gott tut, das ist

wohlgetan”

(“Whatever God does,

that is well done”),

after which the

sermon started

perhaps – though

this Cantata does

not have the usual

two-part dimension,

and does not have

the “prima/secunda

pars” marking.

However that may be,

we are further

taught with a Tenor

secco recitativo

(no. 4), that

“moderation”

is a rule for life,

in contrast to “greediness”,

which only causes “grief

and sorrow”.

The monologue ends

with the sung

‘arioso’ conclusion

“Was Gott tut,

das ist wohlgetan”

(the chorale text

just heard), in

which, on the last

syllable and in a

refined way, the

fallacy of ‘our’

frailty should be

compared to God’s

perfect “wohl-tun”.

A Soprano Aria (no.

5), with obbligato

oboe d’amore and

basso continuo,

develops this idea

of moderation

further. In this

quiet three-part

movement the soprano

and oboe d’amore

engage in peaceful

dialogue in perfect

balance. The

instrumental bass

emphasises the

dialogue with a

steady andante pace

(as the ‘andante’

idea so often does

in Baroque music),

and, so to speak,

symbolises time or

even eternity. The

voice ends the aria

with the word “Genügsamkeit”

(“moderation”),

repeated seven times

in various ways

(once

quasi-unaccompanied,

which possibly is

supposed to

represent

non-action).

The Cantata ends

with a further

simple four-part

Chorale (no. 6)

on a text by Albert,

Duke of Prussia,

1547, “Was mein

Gott will, das

g’scheh allzeit”

(“What my God

wishes, should

always be done”).

Note that in the

last verse, on the

last word

(“verlassen” –

“abandon”), Bach

unfolds a complex

polyphonic texture,

to describe well, in

a dramatic

‘roundabout’ way,

“abandon”.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|