|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25307 - (p) 2007

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25307 - (p) 2007 - rectus

|

|

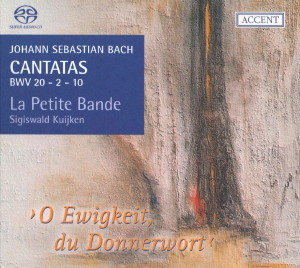

CANTATAS -

Volume 7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

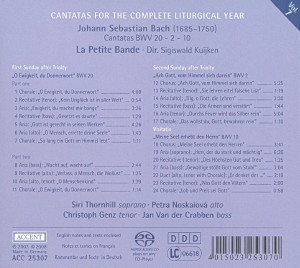

| First Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

"O Ewigkeit, du

Donnerwort", BWV 20

|

|

26' 19" |

|

| Part

one |

|

|

|

-

Choral: O Ewigkeit, du

Donnerwort

|

4'

08"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Kein

Unglück ist in aller Welt zu finden |

0' 54" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Ewigkeit, du

machst mir bange |

3' 26" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Gesetzt,

es dau'rte der verdammten Qual |

1' 29" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Gott ist gerecht

in seinen Werken |

4' 26" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): O Mensch,

errette deine Seele |

1' 43" |

|

|

| - Choral:

So labg ein Gott im Himmel lebt |

1' 11" |

|

|

| Part two

|

|

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Wacht auf, wacht

auf, verlornen Schafe |

2' 44" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Verlass, o

Mensch, die Wollust |

1' 25" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (alto, tenor): O

Menschenkind |

3' 39" |

|

|

| - Choral:

O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort |

1' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Second Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Ach Gott, vom

Himmel sieh darein", BWV 2 |

|

18' 12" |

|

| -

Chorus: Ach Gott, vom Himmel

sieh darein |

5' 25" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Sie

lehren eitel falsche List |

1' 19" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Tilg, o Gott,

die Lehren |

3' 30" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Die Armen

sind verstört |

1' 44" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Durchs Feuer

wird das Silber rein |

5' 04" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Das wollst du, Gott,

bewahren rein |

1' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Visitatio |

|

|

|

| "Meine Seel

erhebt den Herrn", BWV 10 |

|

19' 54" |

|

| -

Chorus: Mein Seel erhebt den

Herren |

3' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Herr, der du

stark und mächtig bist |

6' 26" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Des

Höchsten Gut und Treu |

1' 25" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Gewaltige stößt

Gott vom Stuhl |

3' 04" |

|

|

| -

Duet (alto, tenor) &

Choral: Er denket der

Barmherzigkeit |

2' 19" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Was Gott

den Vätern alter Zeiten |

2' 00" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Lob und Preis sei

Gott dem Vater |

0' 58" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Siri Thornhill,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I (leader) |

|

| Christoph

Genz, tenor |

- Makoto

Akatsu, violin I |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

II |

|

|

- Veronica

Kuijken, violin II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Michel

Boulanger, basse de violon |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe |

|

|

- Yann

Miriel, oboe |

|

|

- Jean-François

Madeuf, tromba solo (20,

no.8), trombone (2, nos.1 and

6)

|

|

|

- Mike

Diprose, tromba da tirarsi |

|

|

- Matthew

Spedding, trombone |

|

|

- Massimiliano

Costanzi, trombone |

|

|

- Ercole

Nisini, trombone |

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - Juli 2007 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25307 - (1 CD) - durata 64'

25" - (p) 2007 (c) 2008 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

"O

Ewigkeit, du

Donnerwort"

- BWV 20

Bach began his

second year of

office in Leipzig

with this Cantata.

It is, at the same

time, the first

Cantata of the year

of his so-called

“Chorale Cantatas”,

those works which

were all based on a

complete chorale

text from the rich

treasury of existing

Lutheran chorales

(in the other

Cantatas Bach mostly

used only one or at

the most a pair of

chorale verses). In

1724-1725 Bach wrote

41 such Chorale

Cantatas (Trinity‚

24 to Easter‚ 25).

Among Bach’s Chorale

Cantatas two types

may be

distinguished. In

the first, the

existing text is

used word for word

and complete,

without any

addition. In the

second, on the other

hand, all the verses

would have been

edited later, but

occasionally poured

into some

combination and/or

new poetic form.

The Cantata BWV 20

belongs (like most

of the Chorale

Cantatas) to the

second type. From

the twelve verses of

the hymn by Joh.

Rist of 1642

(printed in 1682

representing a

shortened version of

the original 16

verses) the unknown

editor combined the

fourth and fifth

verses into one

(Recitativo secco

no. 4). The original

text of the first,

eighth and twelfth

verses were retained

(nos. 1, 7 and 11 in

Bach’s composition).

All the others were

reworked from Rist.

This work was first

heard on the 11th

June 1724.

The text of this

Cantata follows

closely the Gospel

for the First Sunday

after Trinity (St.

Luke 16, 19-31),

which presents to

the faithful the

stern parable of the

poor, ill Lazarus

and the rich man.

The latter allows

Lazarus to die in

misery on his

doorstep, while he

himself lives it up

sumptuously. But

after he also dies

and is buried with

all honours, he

suffers the worst

torments of hell and

sees Abraham afar

off with Lazarus in

his lap. In misery

he begs Abraham for

his help, but the

latter explains that

what had befallen

him was only what he

deserved, and that

on earth he had

received his share

of good things and

Lazarus bad things -

therefore Lazarus

now is comforted,

but he (the rich

man) is tormented

for ever. Hereupon,

the rich man begged

Abraham to send a

messenger to his

five brothers on

earth, to warn them

lest they also come

to this place of

torment, but Abraham

answered that they

had Moses and the

Prophets, and if

they will not listen

to them, then a

message from the

dead will not

persuade them.

For the beginning of

this new cycle Bach

composed an

extremely

theatrical, highly

calculated Cantata

to this text.

Accordingly, he

employed the form of

an overture in the Opening

Chorus (to the

original text of the

first verse of

Rist’s hymn). At fi

rst one thinks that

an opening opera

ouverture in

the purest French

style is being

heard! In the

twelfth bar,

however, with

violent repeated

semiquavers in the

strings, which sound

threatening, the

voices enter. The

soprano, supported

by the slide

trumpet, sings the

chorale melody. This

fi rst line is

simply and

transparently

harmonised. On “Donnerwort”

(word of thunder)

the three lower

voices take on the

pointed rhythm of

the instruments

(through which the

meaning of these

words is strongly

emphasised). The

Overture continues,

and in the

twenty-third bar the

second line starts

(again with repeated

semiquavers), in

which the words “...das

durch die Seele

bohrt” (that

bores through the

soul) are

illustrated anew,

musically and

vividly, by the

lower voices and the

strings. The third

line, “O Anfang

ohne Ende” (O

Beginning without

end), is calmer,

combined with the

continuing Overture.

The instruments

close the slow part

of the ouverture

form after six more

bars, and commence

the customary faster

fugal movement

(Vivace in 3/4

time). Three

contrasting motifs

are interwoven here

by the instruments.

The vocal ensemble

develops the next

three lines in three

sections. Here Bach

portrays, as we

would expect, the

concept of “Traurigkeit”

(sorrow) and “(Ich

weiss) nicht wo

ich mich hinwende”

(I know) not whither

I can turn) very

effectively and full

of affekt.

Five bars later this

middle section

breaks off with a

sudden dissonance (a

fermata increases

the effect here).

Then a return to the

binary time of the

opening follows,

with each time sharp

“interjections” from

the instruments, an

“anticipation“ of

the following text

(seventh line) “mein

ganz erschrokken

Herz erbebt”

(full of fear my

heart trembles), and

now the singers also

take up the

“frightened” rhythm.

The eighth and last

line “dass mir

die Zung am Gaumen

klebt” (so

that my tongue

sticks to the roof

of my mouth) is

clearly shown by the

horizontal

polyphonic tension

in the vocal and

instrumental parts.

This opening

movement contains

many more beauties.

Note for instance

how, on the words of

the third line “O

Anfang ohne Ende”

(O Beginning without

end) several

instruments always

spin out long

sustained notes

(Eternity!), whether

in the bass or the

wind or the upper

strings.

After this

overwhelming

movement there

follows a reworking

of the second

original verse in a

Recitativo

secco for tenor.

The text aims to

remind us in almost

a macabre way, that

such pain has an end

on earth, but that

the pain of hell is

“without release”.

How rhetorical are

the sudden slow

staccato quavers in

the bass for “ewig

dauernd”

(lasting for ever),

a moment of

“non-motion” – time

stands still!

There follows a

passionate tenor Aria

(no. 3), in C

minor, 3/4 time,

with string

accompaniment. This

is a kind of

complaint “Ewigkeit,

du machst mich

bange / Ewig ist

zu lange” etc.

(Eternity, thou

maketh me afraid /

For ever is too long

etc.). As in the

opening chorus Bach

uses long-held

notes, to portray

the concept of

“eternity”,

alternating between

all the parts. The

unease of an anxious

mankind is suggested

continually by

sighing

appoggiaturas. For “Flammen”

(flames) the tenor

presents rapid

semiquavers in a

long vocalise. “Pein”

(pain) gets a long

melisma with large

and difficult

intervals. For “es

erschrickt und

bebt mein Herz”

(it terrifies me and

makes my heart

tremble) we hear a

distant echo of the

same thoughts

described in the

opening chorus.

The Recitativo

secco (no. 4)

for the bass repeats

the idea of the

previous recitative,

but goes more richly

and more fully into

the description of

earthly suffering

(which can last

incredibly long, but

will stop at some

time) and the

eternal punishments

of hell, “die

Zeit, so niemand

zählen kann /

fängt jeden

Augenblick / zu

deiner Seelen

ew’gen Unglück /

sich stets vom

neuem an”

(Time, which no one

can count / catches

every moment / of

eternal misery for

thy soul / eternally

renewed). The myth

of Sisyphus is not

far away!

In the next Aria

(bass, three oboes

and basso continuo)

(no. 5) the

description of hell

is not extended. We

are assured how just

God’s judgement is:

“Gott ist gerecht

in seinem Werken /

Auf kurze Sünden

dieser Welt. Hat

er so lange Pein

bestellt / Ach

wollte doch die

Welt dies merken

/” etc. (God

is just in His

works; / for brief

sins in this world /

He has decreed such

long pain; / Ah!

Would the world but

take note of this! /

The time is short,

death swift, / think

on this O child of

man! Etc.). In truth

a miserable

prospect; how

distant is God’s

mercy here.

Bach goes so far as

to set this text to

cheerful music. Thus

(it seems to me) the

instruments

illustrate God’s

indestructible joy

in himself and his

purpose - the three

oboes in “close

harmony” symbolise

the Holy Trinity

well, with carefree

interaction, in

which they are

joined by the basso

continuo and the

solo singer. The

rhythmic staccato

arpeggio motif in

quavers at the start

of the basso

continuo surfaces

again and again, and

easily anticipates

the scansion of the

text “Gott-ist-ge-recht”

or “Die-Zeit-ist-kurz”,

even if it is not

yet there.

Here the chief idea

of the Gospel lesson

really comes

through; the

eternally valid

“Judgement”.

There follows here

(almost like an

epilogue) the Aria

(no. 6) “O

Mensch, errette

deine Seele /

Entfliehe Satans

Sklaverei”

etc. (O Man, save

thy soul / escape

from Satan’s slavery

etc.). The alto

soloist, with string

accompaniment,

really dances a

courante! Here Sofia

(Wisdom), elegant

and petite, appears

to us from heaven on

high to give us a

golden piece of

advice. Even more

than in the previous

aria this truly

“courtly” music has

a disconcerting

effect - gripping.

The first part of

this vivid Cantata

closes with a simple

Chorale (no. 7).

The text is

literally the eighth

verse of J. Rist’s

hymn of 1642, which

again sums up the

essence of

everything that has

been said before.

In the second part (Seconda

Pars) of

this work - probably

played after the

sermon - the poet

shows us how we can

avoid paying the

price of eternal

torments in hell.

No. 8 is an Aria

for bass, trumpet,

oboes and strings, “Wacht

auf, wacht auf,

verloren Schafe /

Ermuntert euch vom

Sündenschlafe,”

etc. (Wake up, wake

up, lost sheep /

arouse thyselves

from the sleep of

sin, etc.).

Here the ‘Vox Dei’

rings out -

traditionally a bass

singer and trumpet

symbolise the voice

of God the Father -

as carrier of a

Divine commandment.

It cannot be more

clearly conveyed

than by a dotted

rhythm (at the same

time similar to an ouverture),

as it is portrayed

here.

On the words “eh

die Posaune

erschallt”

(before the trumpet

sounds) Bach

achieves the right

spatial effect with

the echoing

interplay between

the trumpet and the

other instruments,

while the bass lets

his vocalise ring

out.

In the following Recitativo

Secco (no. 9)

the alto comments

more closely on this

commandment. We must

“Wollust dieser

Welt verlassen, /

Pracht, Hof-fart,

Reichtum, Ehr und

Geld” (abandon

the lust of this

world, splendour,

pride, riches,

honour and money).

These slogans are

scanned strongly and

separately, in which

the basso continuo,

in a very obvious

portrayal, performs

an extreme

fluctuating,

uncertain line,

which, in the

language of Baroque

music, is often used

to depict a ship

almost sinking in a

stormy sea. Life

should be lived as

if every day was the

last; “man kann

noch diese Nacht

den Sarg vor deine

Türe bringen”

(even on this night

the coffin could be

brought to your

door).

With the Duetto

(no. 10) for

alto, tenor and

basso continuo we

find ourselves for

the last time in the

disconcerting

atmosphere which

dominated the end of

the first part of

this Cantata. Once

again we hear the

warning “Voice of

God” - but now with

two voices! (A

“unison” which is

really “two” - does

Bach not mean the

Son and Holy Ghost

here, in his inner

imagination? -

Maybe...) “O

Menschenkind / Hör

auf geschwind /

Die Sünd und Welt

zu lieben...”

(O Child of man,

cease quickly / from

loving sin and the

world...). The music

has a strange

“objective” but kind

aspect here, as in

Aria no. 8. So the

pointedly

“artificial” dryness

at the beginning,

where the start of

the text “O-Mensch-en-kind”

is recognised in the

bare, staccato,

ostinato motif of

the continuo - and

also “hor-auf-ge-schwind”,

and later “dass-nicht-diePein”

(that not the pain)

and “...am-reich-en-Mann”

(in the rich man).

The movement seems

to be almost

wrathful in its

abstract

construction. Above

all, the basso

continuo never gives

up its sternness -

in the solo voices

it is approached

more expressively

with a firm

authority, even up

to the extreme

chromaticism on the

words “Heulen

und Zahnklappen”

(wailing and

gnashing of teeth),

as well as “betrüben”

(oppress). “Qual”

(torment) and “Tröpflein

Wasser” (drop

of water) receive

supple and

appropriate figures.

The Cantata BWV 20 (no.

11) ends with

the original twelfth

verse of the hymn

from 1642 (1682).

The movement is

musically identical

to the Chorale at

the end of the first

part, only the text

is different. The

first six lines

repeat word for word

the six opening

lines of the first

verse - but then it

differs: “Nimm

Du mich, wenn es

dir gefällt / Herr

Jesu, in dein

Freudenzelt”

(Take Thou me, if it

pleases Thee / Lord

Jesus, into Thine

pavilion of joy).

"Ach

Gott, vom Himmel

sieh darein" - BWV

2

Bach wrote

this work for the

Second Sunday after

Trinity in 1724, the

18th June. It was

performed a week

after the previous

Cantata in our

recording, BWV 20,

mentioned above. It

is also a Chorale

Cantata.

The text is based on

Luther’s translation

(reworking rather,

from 1524) of the

twelfth Psalm.

Luther extended this

short Psalm into a

hymn with six verses

each of seven lines.

The first and last

of these Lutheran

verses were adopted

unchanged, the

others were altered

by an anonymous

editor from Bach’s

time for the

recitatives and

arias, in which,

here and there, a

line is quoted with

the original word

order. (We will see

that Bach then

treated these lines

in a particular

way).

Bach had often

attached great

importance to

providing

contrasting

compositions from

one Sunday to the

next. As an absolute

opposite to the

“modern” opening

chorus of BWV 20,

which the

congregation had

heard on the

previous Sunday,

here was an

“old-fashioned”

Cantus firmus Motet

as the first

movement. The

text portrays for us

the lonely and

disillusioned

faithful, who beg

their Lord for His

help and mercy in

this wicked world.

The Cantus firmus

(the chorale melody)

is taken in “double

length” notes (as

very often

traditionally) by

the alto, with long

pauses between the

lines. The three

other voices always

anticipate the motif

of each line in

“simple” note

values. One after

another they join in

with their

respective motif,

and only when all

three have

introduced this

motif

polyphonically, does

the Cantus firmus

join in with the

chorale section

which has been

“presented”. This

process is repeated

seven times, until

the end of the

verse. In the second

and fourth sections

(second and fourth

lines) Bach has

“adapted” the Cantus

firmus a little (for

“und lass dichs

doch erbarmen”

[and grant us Thy

Mercy] and “verlassen

sind wir Armen”

[we poor ones are

forsaken]), so that

the melody on “erbarmen”

and “Armen”

really displays a

plaintive

chromaticism. This

modest alteration

immediately gives

the whole opening

movement an affekt

of pain. (In the

closing chorale of

the Cantata (no. 6)

one hears the

original “neutral”

form in the soprano

- without

chromaticism!).

This “opening motet”

shows Bach as the

absolute master of

the “old” style. So

the consecutive

fragments which

follow are combined

in an astonishing

way into an

ever-flowing, strong

counterpoint, in

which the basso

continuo is

sometimes

independent, but

also sometimes in

unison with the bass

singer or supporting

him an octave lower.

Through this colla

parte doubling of

the vocal part by

the strings, oboes

and above all by the

trombone quartet an

archaic sound is

achieved, that is

fantastically

appropriate for the

affekt and

the style of the

movement.

After this

impressive first

movement there

follows a Recitativo

secco for tenor

- a

paraphrase of

Luther’s second

verse. Here the

troubled believer

expresses in more

detail his critical

thoughts about

faithless mankind.

The Baroque poet has

again used two

verses of Luther’s

original almost word

for word. This is

not set by Bach in a

free recitative

but in a measured

Adagio tempo.

He makes use of the

old chorale melody,

as it was in the

hymn to these words,

and even allows it

to be played

canonically each

time by the

continuo. It deals

with the opening

words, “Sie

lehren eitel

falsche List”

(They teach vain,

false cunning) and “Der

eine wählet dies,

der andre das”

(The one chooses

this, the other

that). The other

(new) lines are set

in the usual secco

style, with all the

familiar Baroque

characteristics of

declamation and

textual

interpretation.

The Aria (no. 3)

for alto, solo

violin and basso

continuo follows: “Tilg,

O Gott, die Lehren

/ So dein Wort

verkehren”

(Destroy, O God, the

doctrines / which

pervert Thy Word).

The rhythmic and

“eloquent” chief

motif of the basso

continuo,

immediately imitated

by the solo violin,

clearly scans the

core words of the

text: “Tilg, O

Gott, die Lehren”.

This motif is

repeated as a

neverending idée

fixe in the continuo

a dozen times during

the course of the

aria, and is taken

up by the violin and

the solo voice. The

(false) “Lehren”

(doctrines) and the

“verkehren”

(to pervert) are

represented by the

solo violin (less by

the singer) with

many nervous

semiquaver triplets.

When the poet

arrives at the line

“Trotz dem, der

uns will meistern”

(Defy Him, who would

master us), (the

sense of this line

is: “Listen not to

them - God!

- who would tell us

how we should

live”!), Bach

suddenly goes back,

in the vocal line of

the last section, to

the original melody

of the Lutheran

hymn. This line is

actually almost

identical to the

original Lutheran

text - which is why

Bach wishes it to be

heard as in the

original hymn, even

though this fragment

stands as an

isolated foreign

body in the current

musical context.

After this the Bass

takes on the

paraphrased Fourth

Verse of the Hymn

(an Accompanied

Recitative

with strings). Here

at last the

complaints of the

anguished believers

are heard by a

merciful God - the

‘Vox Dei’, full of

mercy, says: “Ich

hab ihr Flehen

gehört (...) Mein

heilsam Wort /

Soll sein die

Kraft der Armen”

(I have heard their

pleas (...) My

healing Word shall

be the strength of

the poor). This

comfort is declaimed

in a flowing Arioso,

in which the string

accompaniment

sometimes imitates

the voice.

The Tenor Aria

(no. 5) “Durchs

Feuer wird das

Silber rein”

(Through fire the

silver is purified)

(with strings and

oboes) follows. The

text of this very

affirmative aria

emphasises how the

true Christ achieved

His spiritual

salvation through

the patient

endurance of His

Cross and suffering.

The constant

simultaneous

repetition of

thematic

combinations of two

widely separated

scale fragments (for

instance the upper

voice against the

basso continuo)

probably suggests

here the “difficulty”,

the apparent paradox

of this stance of

the faithful.

The closing Chorale

(no. 6)

presents the last

verse of Martin

Luther’s hymn in the

original wording,

richly and

affectionately

harmonised.

"Meine

Seele erhebt den

Herrn" - BWV 10

(For the Feast of

the Visitation of

the Blessed Virgin

Mary, the 2nd

July)

This Cantata was

performed on the 2nd

July, 1724, two

weeks after the

above Cantata BWV 2,

(in this year the

Fourth Sunday after

Trinity coincided

with the Festival of

the Visitation of

the Blessed Virgin

Mary, which is

always celebrated on

the 2nd July).

Like BWV 20 and BWV

2 this work is also

a Chorale Cantata.

The text is an

anonymous reworking

of Luther’s

translation of the

Magnificat.

The Magnificat is

one of the best

loved and most

highly valued hymns

in the liturgy.

Every service of

Vespers in the

church closes with

this text. It is the

spontaneous song of

praise for the Lord

by the Virgin Mary,

as it is handed down

in the Gospel

according to St.

Luke (1, 46-56).

The context is as

follows (St. Luke 1,

39-45): Mary

visits her old

cousin Elisabeth,

in a city in the

hills of Judæa.

She salutes

Elisabeth and,

when Elisabeth

heard the

salutation of

Mary, the babe

leaped in her womb

(she is pregnant

with the child, who

one day would be

John the Baptist), and

she said unto

Mary: “Blessed art

thou among women,

and blessed is the

fruit of thy womb.

And whence is this

to me, that the

mother of my Lord

should come to me?

For, Io,

as soon as the

voice of thy

salutation sounded

in mine ears, the

babe leaped in my

womb for joy. And

blessed is she

that believed, for

there shall be a

performance of

those things which

were told her from

the Lord.”

(That is, it had in

the meantime been

announced to Mary by

the angel Gabriel,

that she would bear

a child by the Holy

Ghost, and that he

would be called

Jesus, Son of God.)

Mary immediately

knew the reason

for Elisabeth’s

reaction, and sang

the praises of the

Lord with

the words of the

“Magnificat”

(“My soul doth

magnify the Lord”,

etc.).

This is one of the

most important

“moments“ in the

Christian mythology.

In Bach’s time this

Magnifi cat was sung

in German in the

church service to

the Gregorian melody

in the ninth Psalm

Tone. Bach also used

this bipartite

melody as the

chorale in this

Cantata

(incidentally it

should be noted that

Mozart also used the

same Gregorian

melody in the first

and last movements

of his famous

Requiem).

The text editor of

this Cantata has

quoted unchanged the

beginning of the

German Magnificat

(that is the prose

text of the Opening

Chorus). He

has also retained

the original wording

in the fi fth

movement, which was

so well-known to the

congregation, (Duetto

“Er denket der

Barmherzigkeit”,

etc. [In remembrance

of His Mercy etc.])

as well as in the

seventh movement (Choral

“Lob und Preis”

etc. [Glory and

praise etc.]). This

is the so-called

“doxology”, the

usual closing eulogy

for the Christian

Trinity. In all the

remaining movements,

however, this

Baroque poet has

reworked the

original German

text.

Bach’s composition

begins with a

magnificent Opening

Movement (no.

1: Vivace, G

minor, with strings,

oboes and trumpet

together with a

vocal quartet).

Right at the

beginning of the

movement the tone is

set; festive and

inwardly eventful,

enthusiastic. Under

the dialogue of both

the upper voices

(violins and oboes

in unison) a clear

bass line stands

out, with an

obstinately repeated

“anapest” rhythm (short,

short long, a

figure

full of enthusiasm).

This line is the

“foundation” of the

whole movement. Not

by chance does it,

above all, rise (“Meine

Seel erhebt den

Herren”!) (My

soul doth magnify

the Lord!).

The four sections of

this part of the

text are sung to the

above chorale with

long notes (doubled

by the trumpet), the

first two by the

soprano and the last

two by the alto -

the latter repeats

the complete “Cantus

firmus” a fifth

lower. The other

voices, meanwhile,

contribute to the

lively instrumental

texture. Immediately

after the alto has

completed the last

words of the text

set to the chorale

melody, Bach repeats

the last section of

text, “Siehe,

von nun an werden

mich selig preisen

alle Kindeskind”

(Behold, from

henceforth all

generations shall

call Me blessed), in

a free coda, in

which all the four

singers are equally

engaged. Long

enthusiastic

vocalises on “Preisen”

and “alle”

show Bach’s

involvement with the

text.

A Soprano Aria

(no. 2), “Herr,

der du stark und

mächtig bist”

(Lord, Thou who art

strong and mighty)

follows - a

reworking of St.

Luke’s verse 49. The

affekt of

this brilliant aria

is very close to the

opening chorus. The

still very young

Mary (therefore a

soprano here) thanks

the Lord for all the

great things He has

done to her.

Bach sets the aria

in B major, the

relative major key

for the G minor of

the opening

movement. The rising

main motif and the

concertante style of

writing illustrate

Mary’s enthusiasm

for the might and

strength of God.

In the Recitative

(no. 3) for

tenor we again find

the contents in St.

Luke’s verses 50-51.

These display two

contrasting

thoughts. On the one

hand, God’s mercy is

on them that fear

Him, and on the

other hand, the

power of his arm, if

that is needed,

punishes the

halfhearted

Christians and

scatters like chaff

(“wie Spreu zu

zerstreun”)

the proud and

haughty. Above all,

this second thought

is portrayed by Bach

in this Baroque kind

of recitativo

secco (for

example the virtuoso

vocalise on “zerstreun”

[scatter]).

The Bass Aria

(no. 4), which

follows next,

“adapts” the next

two verses of St.

Luke’s text. How God

has put down the

mighty from their

seats, and exalted

them of low degree.

(Yes, the young

enthusiastic Mary is

overjoyed by the

hidden power of

God.)

This aria is set for

bass and basso

continuo alone - it

contains one of

Bach’s most figured,

concertante continuo

parts. The original

source has only “continuo”,

without any further

instructions about

instrumentation. It

is clearly

discernible that

this apparently very

solo-like part is

conceived for the

“8-foot violone”

tuned Cgda

(transcribed by us,

in the interests of

greater clarity, for

“basse de violon”

(bass violin), the

important larger

version from those

days of today’s

cello), in which,

above all, it uses

the deeper part

of the tessitura

of this instrument.

Accordingly, in this

piece, a

“violoncello” is out

of the question

(incidentally the

whole Cantata - like

most of the others -

contains no

violoncello part).

For the vocal part a

bass is the

best-suited to

illustrate the might

of the Pantocrator -

the power of God the

Father. The whole

aria is performed in

the low register,

and throughout Bach

wishes to make hell

plain (the “Schwefelpfuhl”,

the sulphur pool),

and the whole

content of this text

is linked to the

deeper forces. The

vocalises of the

bass soloist

occasionally

illustrate the text

in a direct, vivid

way, as on the “Gewaltige”,

(the mighty) “hinunter

in den

Schwefelpfuhl”

(into the sulphur

pool) and on “bloß

und leer”

(bare and empty).

No. 5 (Duet and

Chorale) is,

as we have

mentioned, the

original version by

Luther of St. Luke’s

verse 54, namely the

(prose) text “Er

denket der

Barmherzigkeit und

hilft seinem

Diener Israel auf”

(In remembrance of

His Mercy, He hath

holpen his servant

Israel) (the Latin

text “suscepit

Israel” etc.

in the Magnificat).

Bach wrote it for

alto and tenor, with

basso continuo - in

which the chorale

(without words) can

also be heard on the

slide trumpet with

long notes, as a

memory of the main

text.

Musically,

mercy is portrayed

here as being tied

in with the sorrows

of mankind, through

countless painful

“sighs”

(appoggiaturas).

Thus Bach shows us

“mercy” as

“compassion”. The

piece is almost a lamento,

sung under the

“umbrella” (in the

chorale the

trumpet!) of God’s

help.

The Accompanied

Recitative (no. 6)

for tenor and

strings is once

again a free

reworking of St.

Luke’s text (verse

55). Here the

connection to the

Old Testament is

established, which

is God’s promise to

Abraham and Sara,

that Sara would, in

spite of her age,

give birth to a son,

namely Isaac, whose

lineage (from St.

Matthew 1, 1-16)

eventually leads to

the birth of Jesus.

(Here it should

briefly be noted

that St. Matthew’s

Gospel is different,

in that there Joseph

is Mary’s husband

and there is no

mention of a “dove

from the Holy

Ghost”).

The recitative is secco

until the words “Sein

Same musste sich

so sehr / Wie Sand

am Meer...”

(His seed would

multiply like the

sand on the

seashore), when the

strings enter with a

portrayal, which

reminds us, with

soaring flakes, of

the spreading

lineage of Abraham.

Like so many

cantatas, this one

closes with a simple

Chorale (no. 7).

It is as is said in

the literal

phraseology of the

old German text for

the doxology “Lob

und Preis sei dem

Vater und dem Sohn

und dem Heiligen

Geiste” etc.

(Glory be to the

Father and to the

Son and to the Holy

Ghost etc.). Until

the last section of

text, “Und von

Ewigkeit” etc.

(and world without

end etc.), the

movement is

relatively simple

and homophonic - but

then it closes with

a beautiful

horizontal

polyphonic final

phrase.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|