|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25306 - (p) 2007

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25306 - (p) 2007 - rectus

|

|

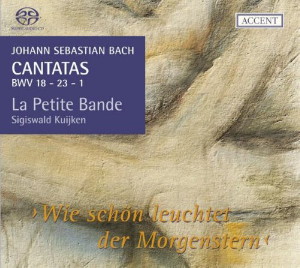

CANTATAS -

Volume 6

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

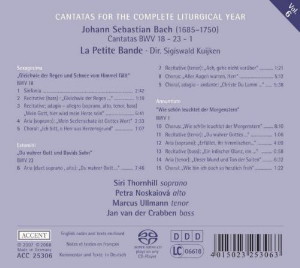

| Sexagesimæ |

|

|

|

"Gleichwie der

Regen und Schnee vom Himmel

fällt", BWV 18

|

|

13' 22" |

|

| -

Sinfonia |

2'

42"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Gleichwie

der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel

fällt |

1' 19" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (soprano, alto,

tenor, bass): Mein Gott, hier wird

mein Herze sein |

5' 41" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Mein

Seelenschatz ist Gottes Wort |

2' 33" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Ich bitt, o Herr, aus Herzensgrund |

1' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Estomihi |

|

|

|

| "Du wahrer Gott

und Davids Sohn", BWV 23 |

|

19' 57" |

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, alto):

Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn |

7' 46" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Ach gehe

nicht vorüber |

1' 21" |

|

|

| -

Chorus: Aller Augen warten,

Herr |

5' 12" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Christe, Du Lamm

Gottes |

5' 38" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annuntiato

|

|

|

|

| "Wie schön

leuchtet der Morgenstern", BWV 1 |

|

22' 17" |

|

| -

Chorus: Wie schön leuchtet

der Morgenstern |

8' 10" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Du wahrer

Gottes und Marien Sohn |

1' 06" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Erfüllet, ihr

himmlischen göttlichen Flammen |

4' 09" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Ein

irdischer Glanz, ein lieblich Licht |

0' 58" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Unser Mund und

Ton der Saiten |

6' 32" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Wie bin ich doch so

herzlich froh |

1' 22" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Siri Thornhill,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin (solo in 1), viola (18),

violoncello da spalla (18,23)

|

|

| Marcus Ullmann,

tenor |

- Ryo Terakado, violin

(solo in 1), violoncello da spalla (18,23) |

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass-baritone |

- Sara Kuijken, violin

(23), viola (18) |

|

|

- Giulio D'Alessio,

violin (1,23) |

|

|

- Katharina Wulf, violin

(1,23) |

|

|

- Annelies Decock,

violin (1,23) |

|

|

- Mika Akiha, violin

(23), viola (18) |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola

(1,18,23) |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon (1,18) |

|

|

- Bart Coen, recorder

(18) |

|

|

- Dimos De Beun, recorder

(18) |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe de caccia (1), oboe

(23) |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe de caccia (1), oboe (23) |

|

|

- Jérémie

Papasergio, bassoon (18) |

|

|

- Claude Maury, horn

(1) |

|

|

- Helen McDougall,

horn (1) |

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ

415 Hz |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Auditorium

C. Pollini, Padova (Italy) - March

2007 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25306 - (1 CD) - durata 55'

36" - (p) 2007 (c) 2008 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

Cantatas

BWV 18 - 23 -

1

The

Cantatas BWV 18 (As

the rain and snow

fall from heaven)

and BWV 23 (Thou

true God and David‘s

Son) were intended

for the two last

Sundays before Lent,

the “Sexagesima“ and

“Estomihi“ Sundays

(the last was known

as „Quinquagesima“

in the Catholic

calendar).

In the following

weeks, during actual

Lent, no cantatas

were performed in

the Leipzig

churches, apart from

the Feast of the

Annunciation of Mary

on the 25th of March

- even if this Feast

fell within the

period of Lent

according to the

calendar.

The Cantata BWV 1

(How beautifully

shines the morning

star) was written

for this Lady Day

Feast on the 25th

March, 1725.

Thus, in a way,

these three Cantatas

belong to the same

period in the

liturgical year.

"Gleichwie der Regen und Schnee

vom Himmel

fällt" - BWV

18

This

work comes from

Bach‘s time in

Weimar. Later,

probably in 1724,

the composer

performed this

Cantata again in a

slightly altered

form in Leipzig. It

is the Leipzig

version which is

used in this

recording.

The text is taken

from Erdmann

Neumeister‘s third

year-long series of

cantata texts.

Neumeister was the

most important

author of texts for

this new,

concertante style of

composition.

The structure of the

text is a typical

example of the kind

of texts which

combine different

‘layers‘ from

different sources

with each other. In

this case there are

fragments from the

Old Testament,

Lutheran texts (here

a longer quotation

from Luther, next to

a chorale text from

a contemporary of

Luther, L. Spengler

(1524)), and finally

original poetry from

Neumeister.

The instrumentation

of the piece is

idiosyncratic. There

are no violins here,

but four violas, a

violoncello (for us,

of course, a

violoncello “da

spalla“), a bassoon

and basso continuo.

The Leipzig version

recorded here

doubles the two

highest violas

throughout with two

recorders, sounding

an octave higher.

The five-part

instrumental writing

is not exceptional

in Bach‘s Weimar

cantatas, although

four violas (instead

of two violins and

two violas) and

basso continuo is

not commonplace. The

sound colour,

produced by the

recorder doubling in

the Leipzig version,

is absolutely unique

and fascinating.

The Weimar version

was written in G

minor. In the Weimar

churches music at

the time was played

at a high

choir-pitch (about

a=465 Hz, the pitch

at which the organ

was tuned). In

Leipzig, on the

other hand, several

years before Bach

took up his

appointment,

instruments in

general were already

tuned a whole tone

below the organ

(this was tuned, as

in Weimar, at a=c.

465 Hz - the other

instruments at a=c.

415 Hz). Because of

that, the Weimar

cantatas, which Bach

wished to repeat in

Leipzig, were mostly

written out anew by

him and his

copyists, and

actually a tone

higher, so that the

resulting sound, qua

absolute pitch,

(above all because

of the vocal parts)

remains the same.

As a rule Bach used

such rewriting as an

opportunity for a

sometimes very

intrusive revision

of the composition

in question. In the

case of this

cantata, however, he

only added the two

recorders and a

violone, without

altering the actual

composition. In this

adaptation, he

certainly had in

mind a musical idea,

the coherence of

which I would like

to describe briefly

(and purely

hypothetically) thus.

From the remaining

original parts of

this cantata one can

conclude that, for

the performance of

this piece in

Leipzig, the violas

and the violoncello

did not for once

receive the new

parts (transposed

up), and played at

the old Weimar

pitch. They must

also, as in Weimar

earlier, have been

tuned at the high

choir pitch. Only in

Leipzig the

newly-introduced

instruments

(recorders, violone)

played at the deeper

Leipzig pitch, and

therefore received

the new ‚high

notated‘ parts, in A

minor instead of G

minor.

The sound of the

stringed instruments

changes but clearly

belongs to the

altered pitch - I

assume that is why

Bach deliberately

retained the “more

austere“ sound of

the ‘465‘ pitch from

Weimar with four

violas and

violoncello, and

combined them with

the added

instruments (tuned

to a lower pitch and

sounding milder).

The sound of the

augmented

instrumental

ensemble thus

becomes sharper and

more concise, and,

for example in the

introduction, is

very effective in

the evocation of the

rain and snow, which

Bach sets to music.

We tried out this

original combination

of the two voices,

and found it worked

very convincingly.

It is with great

pleasure, therefore,

that we retained it

in this performance.

The piece begins

with a lively

instrumental

introduction - a

Sinfonia, from which

one can very well

understand that the

thematic material

has a descriptive

meaning. The large

intervals and the

general picture from

the unison opening

motifs easily remind

us of the snowfl

akes falling from

the sky. From that

one can also

understand that the

more melodic

horizontal lines of

the two upper voices

are themselves

supposed to depict

the sky from which

the flakes are

falling on the

ground. Did Bach

want to show this

idea even more

clearly in Leipzig

through the addition

of the recorders at

the octave? I

certainly think so.

A recitativo

secco for Bass

follows – the real

textual beginning of

the Cantata. Erdmann

Neumeister literally

borrowed here a long

fragment from the

Old Testament, in

fact Isaiah ch. 55

(v. 10 and 11),

where God himself,

in the fi rst

person, explains to

us how we must

interpret his word.

The choice of a

recitative for bass

solo here, as in

other instances, is

well understood to

be an illustration

of setting to music

the “Vox Dei“, God‘s

voice, which

addresses us

directly. No other

polyphonic

composition to the

same text has ever

had such a vivid

effect as this

extremely

declamatory

recitative.

Note, for example,

the descriptive

madrigalism on the

words ,,...

feuchtet die Erde“

( ... waters the

earth). A descending

line describes the

rainfall. Then note

how, suddenly, with

the indication of a

striding andante

tempo, the words ,,und

macht sie

fruchtbar und

wachsend, dass sie

gibt Samen zu säen

und Brot zu essen“

(and makes it bring

forth and bud, that

it may give seed to

the sower and bread

to the eater) are

given a timeless

weight. Also towards

the end of the text

Bach stipulates

andante once more (...

sondern tun, das

mir gefället,

etc.“) (... but it

shall accomplish

that which I please,

etc.). Voice and

basso continuo are

very imitative here;

no doubt a picture

of continual

obedience.

After this solo

recitative, there

follows a complex

accompanied

recitative. Erdmann

Neumeister writes a

sequence of four

prayers, and, each

time, interrupts

them with a

quotation from

Martin Luther‘s

Litany, ,,Du

wollest deinen

Geist und Kraft

zum Worte geben“

(Thou wouldst give

Thy Spirit and

Strength to Thy

Word). The whole

forms a kind of

excorcism of the

dangers, which

threaten believers

and can separate

them from the true

faith.

Where Neumeister‘s

verse was conceived

in the usual

accompanied

recitative style

(the tenor and bass

taking over

alternately, partly

accompanied by

long-held string

notes, partly in a

declamatory, arioso

dialogue with the

strings), Bach makes

clear use of the

Litany presentation

of the Luther texts.

Luther‘s words are

quoted by the

soprano, “recto

tono“ (on a single

note), with an

accompaniment of

nervous quavers in

the basso continuo

(organ and

‚violoncello‘,

sic!). Finally the

whole vocal ensemble

with instrumental

support answers the

soprano with „erhör

uns, lieber Herre

Gott!“ (Hear

us, dear Lord God!).

Noteworthy and very

effi cient are the

dissonant harmonic

phrases for „...des

Teufels Trug“

(by the devil‘s

deception), and to

illustrate the word

„berauben“

(to rob) in the

first bass phrase

(alternating

movement in the

instruments and

voice) and also „Verfolgung“

(persecution); the

latter was almost

“painted“ (in the

second tenor phrase,

where the tenor

voice seems to chase

the instrumental

bass away).

In this text we are

today struck by

Luther‘s unequivocal

and violent „Und

uns für des Türken

und des Papstes

grausamen Mord und

Lästerungen, Wüten

und Toben

väterlich behüte“

(And from the Turk‘s

and the Pope‘s cruel

murder and

blasphemies, rage

and fury, protect us

like a father). Bach

also supports these

fighting words very

effectively in the

basso continuo,

where the

violoncello runs

free with wild

figures.

Finally, „irregehen“

(to err) is

illustrated by a

long vocalise for

the bass, which

gives the impression

of a plaintive

search.

After this

astonishing

accompanied

recitative comes the

only aria in this

Cantata (most

cantatas have

several arias).

Neumeister wrote: „Mein

Seelenschatz ist

Gottes Wort. /

Außer dem sind

alle Schätze /

Solche Netze, /

Welche Welt und

Satan stricken /

Schnöde Seelen zu

berücken. / Fort

mit allen, fort,

nur fort ...“

(The treasure of my

soul is God‘s word.

/ Apart from that,

all treasures are /

such nets / as the

world and Satan

weave / to enchant

base souls ...).

The upper

instrumental voices,

which, with the

soprano and basso

continuo, weave the

three-part web of

this aria, are

undertaken by the

four violas in

unison and the two

recorders at the

octave. Bach

intended this

explicitly; this

combination of

sounds is extremely

strange, and very

surprising. Perhaps

the sixfold doubling

on the presentation

of „Seelenschatz“

(treasure of my

soul), therefore on

the wealth, should

be pointed out. The

text „Fort mit

allen, fort, nur

fort“ (Away

with them all, away,

only away) Bach sets

with a rising scale

fragment, which, in

a dense canon, is

repeated in the

three parts; the

idea of driving

away.

Once again we can

only be astonished

how, with so many

illustrations of the

text which display a

kind of ‘naïvety‘,

the music does not

descend to being

anecdotal, but

quietly develops its

own unified course.

L. Spengler‘s simple

chorale „Ich bitt, O

Herr...“ (I beg, O

Lord...), harmonised

in a simple way by

Bach, concludes this

particularly rich

piece.

"Du wahrer

Gott und

Davids Sohn" -

BWV 23

Cantata for

“Estomihi“ Sunday

(Quinquagesima) -

Leipzig, the 7th of

February 1723.

Bach performed this

Cantata as his

audition piece, when

he applied for the

post of Thomaskantor

in Leipzig. Begun in

Cöthen, it went

through various

stages before

achieving its final

form. In 1723 it

rang out in Leipzig

with the

reinforcement of

four trombones in

the closing

movement. For later

revivals in 1728-31

these trombones were

dropped. We have

stayed with the

later version.

The unknown author

used, in part, texts

from two lessons.

The Epistle for

Estomihi Sunday was

I. Corinthians, ch.

13, v. 1-13 (Paul

the Apostle‘s famous

text about love),

and the Gospel was

St. Luke, ch. 18, v.

31-42, in which

Jesus announces that

he is going to

Jerusalem and that

he will suffer

there. St. Luke then

tells the story of

the blind man who,

on the road to

Jericho, recognised

Jesus as “David’s

son“, and was healed

of his blindness.

The writer pays no

attention whatsoever

to Paul‘s text, or

to St. Luke’s story

about Christ‘s

intention of going

to Jerusalem etc..

Nevertheless, how

Bach makes room in

his composition for

the narrative of

this prophecy, will

be referred to

below.

The true poetry of

this Cantata deals

only with the story

of the blind man,

who immediately

recognised Jesus as

God‘s son, and was

thereby healed. Thus

ought the Christian

be freed through his

faith; the Christian

begs God for mercy

and strength.

In the text we fi nd

many quotations from

Holy Scripture: from

St. Mark ,,...du

...bist ja

erschienen / Die

Kranken und nicht

die Gesunden zu

bedienen“

(...Thou ...didst

indeed appear/to

serve the sick and

not the healthy),

and from Psalm 145 ,,...Aller

Augen warten, Herr

/ Du allmächtger

Gott, auf dich“

(All eyes wait, Lord /

Thou Almighty God,

for Thee). The text

closes with the

chorale from the

“Agnus Dei“: ,,Christe,

du Lamm Gottes“

(Christ, Thou Lamb

of God).

With the opening

duet, which takes

the place of an

opening chorus, we

are invited, by the

poet and the

composer, to become

absorbed in the

scene, in which the

blind man recognises

Jesus on the road to

Jericho as “David’s

son and the true

God“.

The movement is

marked “Molt’

adagio“ (so to be

played very slowly).

It has the very slow

gait of a (funeral)

march, with the

instruments (2 oboes

and basso continuo)

playing stately

semiquaver triplets

over marching

quavers. Twice, for

two bars, (see

below) the

instruments have a

different theme from

the two singers. The

two oboes are

densely intertwined

in the swirl of

their playing, as

are the vocal parts

(soprano and alto)

in their way. The

two ‘pairs‘ meet

in their difference,

like the blind man

and Jesus. Only

on the words ,,...

mir gleichfalls

Hülf und Trost

geschehen“ (to

me likewise may help

and comfort be done)

do the vocal parts

take for a moment

the same theme as

the oboes (playing gleichfalls

with the same motif

- a picture of

compassion? Without

any doubt... !).

When one of the

singers in the duet

sings ,,... mein

Herzleid“ (my

heart’s grief), it

is always to a

chromatic rising

line. Does this not

show that the

heart‘s grief is

‘directed on high‘,

worshipping God? On

the other hand we

are moved by the

frequent sighing,

sinking fi gure for

,,Erbarm dich“

(have mercy). It is

clear from the

speech in the

Gospel, that the sad

marching “molt’

adagio“ is intended

to be a sign of the

journey to the end

(Jerusalem, the

Crucifixion). We

will meet later yet

another wordless

allusion to this, in

part of the lesson

not developed by the

poet.

The following

recitative for

tenor, two oboes,

strings and basso

continuo can be

viewed as a kind of

‚close-up‘ of the

blind man, as he

explains his plea

further. The

melismas on “fasse“

and “lasse“

well illustrate his

‘turning back‘, his

conversion to the

faith as it were,

after the

recognition of

Jesus.

As mentioned, this

fragment also

contains a wordless

allusion to the

journey of Jesus to

Jerusalem and to the

tragic hidden end.

The two oboes play,

throughout this

accompanied

recitative, the

chorale melody ,,O

Christe, du Lamm

Gottes“ (O

Christ, Thou Lamb of

God), which was

certainly well-known

to the Church

authorities. It must

surely be accepted

that the praying

listeners instantly

recognised this

melody, and

therefore thought

about the

accompanying text.

During this

recitative the

Crucifxion of Jesus

in Jerusalem floats

anew before our

eyes.

After this

“double-layered“

accompanied

recitative the

full-voiced vocal

quartet sing a

highly calculated

choral movement,

which is structured

as a free rondo. The

quotation from Psalm

145 ,,Aller

Augen warten, Herr

/ Du allmächtger

Gott, auf dich“

(All eyes wait, Lord

/ Thou Almighty God,

for Thee) Bach takes

as a (four-part)

ritornello,

introduced by the

instruments. This

ritornello is never

repeated in the same

form, but always set

differently,

although using the

same motif material.

There is heard

throughout, (mostly

hidden in the bass),

the start of the

chorale ,,O Christ,

du Lamm Gottes“,

like a wordless

reminder of the

unused text of St.

Luke.

The poet very

skilfully takes up

in this section the

picture of ‘eyes‘

from the psalm, in

which he uses the

eyes as the subject

of his developing

metaphor. Bach makes

use of these ‚new‘

verses as the

‘couplets‘ of his

rondo. They are

always performed as

horizontally

contrapuntal duets

for tenor and bass,

in which the

instrumental setting

is for the most part

reduced. The whole

has a moving lyrical

character, full of

life.

As the fourth and

final movement of

the Cantata there

now comes, in a very

refined form, a

working of a chorale

(marked “Adagio“ at

the beginning), in

which the chorale ,,Christ,

du Lamm Gottes“,

so often ‘hidden‘,

finally sees the

light of day. This

movement was first

performed in Leipzig

(in 1723, although

in B minor and

reinforced with four

trombones), after

the composition of

the first three

movements had been

finished.

This German

translation of the “Agnus

Dei“, like the

Latin version, has a

three-part

structure. Twice the

plea ,,.. erbarm

dich unser“

(have mercy on us)

rings out, and then

closes with ,,Gib

uns dein‘ Frieden“

(grant us Thy

peace). With the

three sections of

this fragment Bach

leads the way every

time. To start with,

we find the sad

“stride“ of the

opening piece again

(even “Molt‘ adagio“

is found there!) -

the Lamb of God is

brought to mind

here, as it is led

to the sacrifice.

The two oboes

clearly line up ‚on

one side‘, as if

they were privileged

witnesses to the

events, which will

be suggested by the

strings and basso

continuo. The

figure, which the

two oboes present,

is a repeated

‘questioning‘ and

sorrowful, rising

short motif (almost

a “visualisation“ of

those who do not

understand, of the

astonishment of

those who are

witnesses to the

Crucifixion of

Jesus?) The singers

sing with that the

four-part chorale,

more homophonic, but

with expressive

harmonic changes,

compared to the

above-mentioned

‘questioning motif‘

which the two oboes

scatter in the f rst

part of the text,

and then a

plaintive, chromatic

and sinking scale

fragment in the

combined material.

In the second ,,Christe,

O Lamm Gottes“

the tempo indication

changes. Here Bach

writes “Andante“, no

longer “Adagio“ - a

somewhat more

flowing tempo comes

in, though the

emphasis on the

“stride“ remains.

This fragment of the

well-known chorale

melody is now

repeated three times

as a fugue (first by

the soprano, then by

the oboes in unison

and then by the

first violin), and,

combined with a

short head-motif, is

soon extended to all

the voices.

Then the last

section begins (,,Christe,

du Lamm Gottes ...

gib uns dein‘

Frieden“)

(Christ, Thou Lamb

of God ... grant

us Thy peace),

in which the chorale

melody is performed

by the soprano alone

with the first

violin, while the

busy ‘solo-like‘

oboes make a

syncopated contrast

to the regular

stride of the

continuo. In this

whole new material

Bach hides

additionally the

figure of a scale

spanning about an

octave. This figure

is imitated in turn

by the first violin

and the basso

continuo. The image

of peace, which

comes down diffusely

from heaven to

earth?

This elaborate

meditative movement

was used by Bach in

1725, in the second

version of his St.

John Passion, as a

closing chorus in G

minor (although

without the

trombones), but was

later removed from

this Passion. With

the revival of

Cantata BWV 23 in

1728-31 (beginning

in C minor) this G

minor version found

a new use - as

already mentioned,

we present this

version of this

particularly

impressive piece in

our recording.

"Wie schön

leuchtet der

Morgenstern" -

BWV 1

(For the Feast of

the Annunciation,

the 25th of March

1725)

This number 1 of the

BWV

(Bachs-Werke-Verzeichnis)

(Catalogue of Bach‘s

works) in no way

means that this was

Bach‘s first Cantata

or perhaps his first

composition. The BWV

catalogue is not

arranged

chronologically at

all.

This Feast Day of

the 25th March

celebrates the

remarkable story, in

which the Angel

Gabriel appears to

the young Mary, in

order to tell her

that she will give

birth to the Son of

God. Nine months

later, on the 25th

of December, the

church celebrates

the birth of Jesus -

Christmas.

There are

innumerable

depictions in the

visual arts of these

two themes: the

Annunciation to Mary

and the birth of

Jesus Christ (in

which, more often

than not, portrayals

of the three Kings,

their coming and

their adoration of

the Child are

interwoven). In

music we find far

more works, which

join together

Christmas and the

Annunciation.

Cantata

BWV 1 is a chorale

cantata. Such a

cantata is

characterised by a

single Lutheran

hymn. This appears

throughout, so that

either the whole

text of the hymn is

used with all its

verses, or, with the

‘new poet‘, the old

hymn is only partly

quoted word for

word. Mostly (which

applies to this

Cantata) in this

final form the first

and last verses

retain the original

wording, and in the

intervening verses

they are combined in

a paraphrase.

Here the hymn „Wie

schön leuchtet der

Morgenstern“

(How brightly shines

the morning star) by

Philipp Nicolai

(from 1599) is used

word for word in the

opening and closing

verses, and the five

middle verses are

reworked by an

author who is still

unknown.

In 1724 and 1725

Bach wrote this kind

of cantata

exclusively. Our BWV

1 is the last in

this series.

As noted above,

cantata music was

not to be indulged

in during Lent in

Leipzig. An

exception was made

for the Feast of the

Annunciation. If the

25th of March fell

during Lent, fl orid

concertante music

was allowed to take

place during worship

in the churches of

St. Thomas and St.

Nicolai. One can

imagine that such an

opportunity was very

welcome!

It must be added, as

we have said, that

the Feast of the

Annunciation points

towards Christmas -

the Feast for which

it is known that

music plays a star

role.

This ‘Christmas

connection‘ is quite

clearly visible in

Cantata BWV 1. From

the beginning of the

first movement a

richness of sound

holds sway, which

strongly reminds us

of Christmas

‘shepherd music‘. So

Bach moves us

immediately to the

heart of the text.

But he does so

without any

‘triumphal‘

suggestion about the

birth of Christ (for

instance with drums

and trumpets...) -

we are really there

at the Annunciation!

It is more a

question of

portraying the inner

joy.

We will have a look

at the text of this

first movement (that

is the first verse

of Nicolai‘s

original hymn of

1599). The whole

(nine verses) are

clearly in three

groups, which are

each divided into

three verses. The

first two groups are

written in iambic

and the last one in

trochaic rhythm (Lieblich,

freundlich

etc.: long-short).

The (iambic) opening

verse is already

expressive in its

rhythmic tension.

Although “Wie“

is placed on a weak

beat, it is

pronounced with

emphasis just like

the ,,leuchtet“,

which is similarly

placed ‘across‘ the

iambic short-long

scheme. Read through

the next iambic

verses in exact

rhythm, and you will

come across several

such expressive

‘contortions‘ (Voll

Gnad...

Du, Sohn

David).

Also the sudden

change over to

trochaic, in verse

7, is very

effective, and Bach

gratefully exploits

it in his

composition. In the

ninth verse there is

again “... prächtig“

‘across‘ the scheme.

It is always helpful

to recognise such

‘craftsmanlike‘

features. The same

rhythmic shifts,

when appropriate,

profoundly heighten

and colour the

expression of the

text!

Bach‘s composition

is full of

enlightening details

(thus the continual

active illustrations

of the solo violin,

which undoubtedly

portrays the sparkle

of the morning star,

as the Jesus child

is described here).

The sound of the

wind instruments

(horns, oboes da

caccia), and the way

the pairs engage in

dialogue, has a

strange beauty. The

opening interval,

rising a fifth, of

the chief motif is

reused frequently as

a ‘signal‘

throughout the choir

part, with quite a

lot of entries of

different voices.

The six first

(iambic) verses are

all performed in

dialogue with an

instrumental

intermezzo

separating one from

the other. The

soprano (supported

by the first horn)

undertakes the

well-known chorale

melody with long

note values, while

the three lower

voices use the

opening instrumental

motif as the

foundation for their

contrapuntal

material. In the

second and fifth

verses Bach uses yet

another deliberately

contrapuntal trick,

in that he brings

forward the chorale

melody in the tenor

and the alto, twice

in a row, faster and

in canon at the

fifth, before it is

taken up by the

soprano. With the

seventh verse

(beginning of the

trochaic rhythm) ,,Lieblich,

freundlich,

etc.“ (Lovely,

friendly etc.) the

polyphony suddenly

gives way to

homophony. ,,Lieblich“

is sung by the four

voices at the same

time, which quite

clearly emphasises

the idea! Verses

eight and nine, once

again separated by

an instrumental

intermezzo, partly

lean on new

instrumental

material (once again

undertaken by the

three lower

voices!), without

the typical iambic

upbeat of the iambic

part of the

movement. Thus the

groundwork remains

more or less hidden.

The instrumental

introduction is

finally repeated

again ‘da capo‘, in

a splendid symmetry

(at the same time it

must be mentioned

that this

introduction

contains 14 bars; we

come across this

figure frequently in

Bach as a kind of

signature. For

instance, 14 is the

sum of the fi gures

2+1+3+8, which

translates

alphabetically to

spell B-A-C-H, and

the product of

multiplying these

figures is 48. This

number, in all sorts

of combinations of

14 and 48, is worked

in often by Bach as

a signature).

The following

recitativo secco

(no. 2) for the

tenor is also the

beginning of the

‚reworking‘ of the

original text by the

anonymous poet from

Bach‘s time. It

points to Christmas,

,,nach dem die

ersten Väter schon

/ So Jahr‘ als

Tage zählten“

(from which the

first fathers

already / counted

the years and days),

and sings of the joy

which Gabriel‘s

Annunciation had

promised.

The following

soprano aria

develops this theme

in a very lively

fashion: ,,Erfüllet,

ihr himmlischen

göttlichen

Flammen /

Die nach

euch verlangende

gläubige Brust!“

(Fill, ye heavenly,

divine flames / the

faithful breast that

longs for Thee!).

The rhythm of the

text is dactylic

here. It is strictly

used, but (a kind

colleague has

pointed out to me!)

this verse is

dominated by the

metrical unit

‘short-long-short‘,

which is known as an

“amphibrach“. The

repetition of this

metrical unit

finally surrenders

to the binary

dactylic feeling

(long-short-short)

though it starts

with an ‘upbeat‘ at

the beginning of the

verse.

The poetic beauty

actually diminishes

a little in the text

of this aria, but

the musical

invention

compensates for this

weakness completely.

The obbligato part

for oboe da caccia

(note again the

‘shepherd sound‘!)

and the light-footed

pizzicato of the

bass instruments

frame the voice in a

charming way.

After that, in a recitativo

secco (no. 4),

the bass emphasises

particularly that

this joy was not

earthly, but came

from the hand of God

- which is why we

ought to be

thankful.

Previously the

soprano, in her aria

(no. 3), had gone

further into the

preceding tenor

recitative, and here

the tenor aria (no.

5) develops a

clarification of the

idea of gratitude,

which had just been

expressed by the

bass: „Unser

Mund und Ton der

Saiten / Sollen

dir / Für und für

/ Dank und Opfer

zubereiten“

etc. (Our mouth and

the sound of our

strings / ought to

bring Thee / for

ever and ever / our

gratitude and our

offerings etc.) (we

should note in

passing the rhyme of

‘dir‘ and ‘für‘, as

it occurs many times

in the poetry of

that time).

For the

instrumentation of

the aria Bach

borrows from the

content of the text.

No wind instruments

interfere here, only

‘mouth and strings‘

(voice and

strings... )! The

piece flows in a

kind of minuet

tempo, as in a

dance-like

ritornello. Rapid

vocalises follow the

words “Gesang“

and “König“

(‘song‘ and ‘King‘),

in the B-part of the

aria, with “König“

starting on a

long-held unwavering

note.

�This Cantata, which

is particularly rich

in colours, ends

with the last verse

of the original hymn

of Nicolai from 1599

- without, on the

other hand, a

compositional

process which

‘distills‘ the

contents of the

text. The text

speaks of ‘A and O‘,

of completeness

therefore, and also

„Klopf ich in die

Hände“ (I clap

my hands). Bach

takes this idea

literally (not

without humour),

giving the second

horn a solo part -

the first doubles

the chorale melody -

which seems to

suggest

‘completeness‘ (with

faster figures) as

well as the hand

clapping (with

repeated notes).

Although Bach‘s

refinement and his

frequently hidden

devices arouse our

admiration time and

again, we must not

‘lose‘ ourselves in

them. Bach‘s vision,

which cannot be

expressed in words,

of the deeper levels

transcend many times

this extraordinary

‘craftsmanlike‘

talent.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation

by Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|