|

|

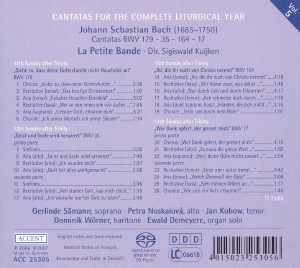

1 CD -

ACC 25305 - (p) 2006

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25305 - (p) 2006 - rectus

|

|

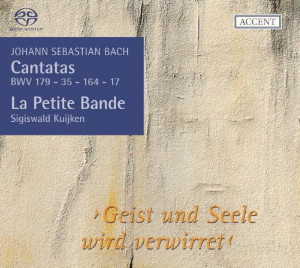

CANTATAS -

Volume 5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

"Siehe zu, dass

deine Gottesfurcht nicht Heuchelei

sei", BWV 179

|

|

15' 23" |

|

| -

Chorus: Siehe zu, dass deine

Gottesfurcht nicht Heuchelei sei |

2'

36"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Das

heut'ge Christentum ist leider

schlecht bestellt |

1' 07" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Falscher

Heuchler Ebendbild |

3' 02" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Wer so von

innen wie von außen ist |

1' 03" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Liebster

Gott, erbarme dich |

6' 21" |

|

|

| - Choral:

Ich armer Mensch, ich armer Sünder |

1' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Geist und Seele

wird verwirret", BWV 35 |

|

26' 06" |

|

Part

one

|

|

|

|

| -

Sinfonia |

5' 50" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Geist und Seele

wird verwirret |

7' 49" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ich wundre

mich |

1' 27" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Gott hat alles

wohlgemacht |

3' 06" |

|

|

| Part

two |

|

|

|

| -

Sinfonia |

3' 46" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ach

starker Gott, lass mich |

1' 19" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Ich

wünsche nur bei Gott zu leben |

2' 48" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

13th Sunday after

Trinity

|

|

|

|

| "Ihr, die ihr

euch von Christo nennet", BWV

164 |

|

15' 56" |

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Ihr, die ihr

euch von Christo nennet |

4' 16" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Wir hören

zwar, was selbst die Liebe spricht |

1' 48" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Nur durch Lieb

und durch Erbarmen |

4' 17" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Ach

schmelze doch durch deinen

Liebesstrahl |

1' 19" |

|

|

| -

Aria [Duet] (soprano, bass):

Händen, die sich nicht verschließen |

3' 15" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ertöt uns durch dein

Güte |

1' 01" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Wer Dank

opfert, der preiset mich", BWV

17 |

|

15' 05" |

|

Part one

|

|

|

|

| -

Chorus: Wer Dank opfert,

der preiset mich |

4' 15" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Es muss

die ganze Welt ein stummer Zeuge

werden |

1' 07" |

|

|

| -

Aria (soprano): Herr, deine Güte

reicht, so weit der Himmel ist |

2' 54" |

|

|

| Part two |

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Einer

aber unter ihnen |

0' 42" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Welch Ubermas der

Gute |

3' 08" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Sieh

meinen Willen an, ich kenne, was ich

bin |

1' 17" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Wie sich ein Vat'r

erbarmet |

1' 44" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerlinde Sämann,

soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I and viola da spalla |

|

| Jan Kobow, tenor |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

I |

|

| Dominik Wörner,

bass-baritone |

- Giulio D'Alessio,

violin II |

|

|

- Ann Cnop, violin

II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Marian Minnen, basse

de violon

|

|

|

- Koji Takahashi, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Marc Hantaï, traverso |

|

|

- Yifen Chen, traverso |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe/taille |

|

|

- Yann Miriel, oboe/taille |

|

|

- Vinciane

Baudhuin, oboe/taille |

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ

and organ solo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schloss

Seehaus, Markt Nordheim (Germany)

- August 2007 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25305 - (1 CD) - durata 73'

55" - (p) 2006 (c) 2007 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

"Siehe

zu, dass deine

Gottesfurcht nicht

Heuchelei sei"

- BWV 179

(for

the 11th

Sunday after

Trinity)

Bach wrote this

cantata in his first

year in office

(1723) for the 11th

Sunday after Trinity

(8th August). Some

15 years later he

used the opening

chorus and the aria

no.5 in his Lutheran

Masses BWV 236 and

BWV 234 (as the "Kyrie"

and the "Qui

tollis").

The opening chorus

is astonishing in

the complexity of

its composition -

even more so, if one

is told how Bach, in

this movement, uses

traditionally strict

compositional

precedents from the

old polyphony as an

illustration of the

text. The Old

Testament saying

from Jesus of Sirach

(1, 34) "Siehe

zu, dass deine

Gottesfurcht nicht

Heuchelei sei, und

diene Gott nicht

mit falschem

Herzen"

("Make

sure that thy fear

of God is not

hypocrisy, and serve

not God with false

hearts")

brings Bach to the

idea that‚

hypocrisy‘ must be

put in a strict

counter-fugue - thus

named in a fugue, in

which each

neighbouring

thematic entry is

the‚ inversion‘ of

the previous one.

Every interval in

the process is used

in the other

direction (for

example rising

fifths become

descending fifths,

etc.). Because the

rhythm also remains

unchanged in this

‘inversion‘, the ear

recognises this

‚new‘ theme as a

similarly equal

‘building block‘ of

the fugue.

Undoubtedly, in my

opinion, this 'inverted'

imitation interprets

the ‘hypocrisy. This

is none other than a

false, feigned

(from the 'inversion')

imitation of the 'truth'?

This �rigorous

counter-fugue is 36

bars long. Then a

new subject comes

into play, based on

the words "diene

Gott nicht mit

falschem Herzen"

("serve

not God with false

hearts"),

which Bach sets for

6 bars as a pure

canon at the fifth.

That means that the

new motif comes in

here six times in

succession

canonically, in

itself unchanged,

but each time a

fifth 'higher'

(as if on a planned

circle of fifths);

for the first time

beginning on g, till

the last time six

fifths 'to

the right',

beginning on f

sharp. This

progression, of pure

canon in a sequence

of rising fifths,

illustrates well (in

sharp contrast to

the counter-fugue

for 'hypocrisy')

the ‘clear, forever

repeating – and

climbing! - command‘

which is pronounced

in this section of

the text. This

canonic section

breaks off after 6

bars (note also the

proportion: 36 bars

of ‘hypocrisy‘

compared to 6 bars

of ‘clear

proclamaton‘...; not

only ‘longer‘

against ‘shorter‘,

but also 6x6 = 36!

What is Bach playing

at here??? - only a

fondness for

mathematics?). From

then until the end

he follows a freer

and more expansive

contrapuntal

treatment of already

used material. At

the same time the

typical madrigalism

on ‘false hearts“

should be noted;

chromatic notes

following one

another (rising and

falling) to

illustrate clearly

the ‘unsafe‘, the

‘false‘...

After this

impressive opening,

which depicts the

“motto“ of the

cantata so

artistically and

vividly, the (still

anonymous) Baroque

poet starts with his

initially fiery

language.

The secco recitative

for tenor (no. 2)

presents an

extremely negative

picture of a

‘lukewarm‘ and

hypocritical

Christian, with many

allusions to the

scriptures (among

others the Sunday

Gospel). The

(iambic) rhythm runs

undisturbed through

the verses; �these

are of unequal

length one from the

other, and thereby

appear irregular and

hesitant - the

‘agitation‘ of the

poet?

The text of the

following aria is

similarly stretched,

where the tenor

(with oboes and

string

accompaniment)

develops the

portrait of the

hypocrite further,

and sums up: "Heuchler,

die von aussen

schön/Können nicht

vor Gott bestehn"

(Hypocrites, though

outwardly fair /

Cannot exist in

God‘s presence). The

text is trochaic, as

one would expect for

such an aria. The

instrumental upper

voice (oboes and

first violins in

unison) and the solo

singer carry on a

dialogue with

similar motifs,

alternately and

sometimes at the

same time.

In the secco

recitative for the

bass (no. 4) the

poet decides instead

to abandon his

negative position,

and to show

positively how the true

Christian ought to

be. This section is

also coloured by

allusions to the

scriptures (as is

the soprano aria

which follows).

Purely declamatory

‘secco‘ lines

alternate very

meaningfully in this

recitative with more

‘arioso‘ statements

of the main ideas

(for example at the

end: "So

kannst du Gnad und

Hülfe finden",

"Thus

canst thou find

grace and help").

The soprano aria "Liebster

Gott, erbarme dich"

("Beloved

God, have mercy")

(no. 5) is a

four-part weave (2

oboi da caccia,

soprano and basso

continuo) of

exceptional tone

colour and design.

As when a ritornello

returns the opening

phrase time and

again throughout the

aria, at different

pitches however, a

five-bar bass line

rising bar by bar

(like an archaic

basso ostinato)

supports the

dialogue between the

two oboi da caccia,

to be joined

sometimes by the

soprano. In the last

verse ("Ich

versink in tiefen

Schlamm",

"I

am sinking in deep

mire")

the usually rising

bass line also sinks

to the earth. A few

bars later the solo

voice, for her part,

is also quite

explicit �with the

sinking line of "Jesu,

Gottes Lamm, ich

versinkt"

("Jesus,

Lamb of God, I am

sinking").

The madrigalism can

hardly fail in this

context.

The closing chorale

follows: "Ich

armer Mensch, ich

armer Sünder"

("I

am a feeble man, a

feeble sinner", the

first verse of a

song by Christoph

Tietze, 1663).

Bach‘s harmonisation

of this simple

melody is shaped

very expressively,

as the main idea,

“have mercy“,

requires.

"Geist

und Seele wird

verwirret"

- BWV 35

(for

the 12th

Sunday after

Trinity)

This Cantata was

composed for the

12th Sunday after

Trinity in 1726 (8th

September). It is a

solo cantata for

alto. The

instruments involved

are: 2 oboes, alto

oboe (known as

“taille de hautbois“

or tenor oboe),

strings and ‘organo

obbligato‘ –

i.e. a concertante

organ.

The text is by Georg

Christian Lehms

(1684-1717), from

1710 Court Poet and

Librarian at the

Court of Darmstadt.

Lehms was a

versatile poet,

writing opera

libretti and secular

poems. From his four

cantata cycles

various cantatas

were set by Chr.

Graupner and J. S.

Bach among others

(Bach 10 works in

total).

The lessons for this

12th Sunday after

Trinity have a

deeper meaning, and

lead the poet and

listener into the

inner contemplation

of God‘s nature and

his miracles. Lehms

combines in his

poetry the epistle

and the gospel

lessons: The Second

Epistle of Paul the

Apostle to the

Corinthians (ch. 3,

v. 4-11), where the

Apostle describes

the glory of God and

the effect of His

spirit on mankind in

the new alliance,

and the recovery of

the deaf and dumb in

the Gospel according

to St. Mark. Many

allusions find their

way back in his

text; a closing

chorale is omitted.

This Cantata is

purely an extended

Baroque reworking of

the main themes, a

passionate monologue

by the poet - and as

such Bach puts it in

the mouth of one

single singer, the

alto.

This Cantata is also

a kind of organ

concerto. Only in

the two secco

recitatives (numbers

3 and 6) the organ

accompanies as usual

- in all the other

movements, however,

it plays a

significant solo

role. It remains

uncertain whether

Bach had been moved

to use again just

for this cantata an

earlier instrumental

composition (from

the Cöthen period?).

It seems to me that

the leitmotif of

God‘s miracles

(which runs through

the whole text) may

have been the basis

of this decision.

What other sound

than the sound of an

organ could ever

illustrate more

suggestively this

idea of the

miracles? In church,

organ music, which

sounds literally

‘from above‘, was

the original symbol

of ‘music from

heaven“.

As a result of this

double decision, the

whole text was

delivered as an alto

monologue, and the

constant and

conspicuous role

assigned to the

organ earns this

Cantata a quite

special place in

Bach‘s church music.

The Cantata is in

two parts, and was

probably played

before and after the

sermon.

The first part

starts with an

instrumental

movement, entitled ‘concerto‘.

The setting is very

colourful. The

concertante organ is

not only accompanied

by the usual string

band, but

additionally by 2

oboes and a ‘taille‘

(alto oboe). This

‘concerto‘ is based

on an earlier, lost

work (oboe

concerto?) of which

only 9 bars are

known, in fact in an

adaptation for

harpsichord and

strings together

with a single oboe.

This movement was

the first movement

of the lost

concerto.

The first aria

follows. It is

certain that this

piece, a kind of

‘siciliano‘ in 6/8

time, was originally

the second movement

of the concerto. The

alto voice

interposes itself

into the existing

ensemble, the

re�arrangement of

the aria being made

with immense skill.

The opening verse

proclaims: "Geist

und Seele wird

verwirret / Wenn

sie dich, mein

Gott betracht‘ /

denn die Wunder,

so sie kennet /

(...) Hat

sie taub und stumm

gemacht".

("Spirit

and soul are

bewildered / When

they contemplate

Thee, my God. / For

the miracles of

which they have

knowledge / (...)

have rendered them

deaf and dumb.")

The dumbness from

astonishment is the

kernel here. In the

original siciliano

movement it was a

fact that the

repeated bars quite

obviously broke the

continuity (the 'interruptio'

was a favourite

stylistic device).

This episode fits in

well with the text

(the bewilderment,

the dumbness!). With

the entry of the

voice after the

opening ‘tutti‘

ritornello the web

of sound changes

suddenly and

completely. The

basso continuo group

falls silent, and

the strings and

taille take over, in

unison and lightly,

the bass an octave

higher. This

produces a

fascinatingly

transparent

five-part texture

from 2 oboes, organ

(right hand only),

alto voice and

“bassetto“. This

sound picture

alternates with the

colour of the

opening ritornello,

until finally (in

conclusion to part

A) the sound of the

tutti comes in under

the voice.

In part B the ‘rejoicing‘

of the people is

strikingly suggested

by a trumpet-like

motif ringing out in

a dialogue between

the organ and the

voice, in which the

woodwind and the

higher strings

answer each other

rhythmically. After

these three

‘festive‘ bars the "...hat

sie taub und stumm

gemacht"

("have

rendered them deaf

and dumb")

has a very

suggestive effect,

in the way Bach has

set them to music.

In the secco

recitative that

follows the poet

tries to indicate

the eternal,

incomprehensible

wonder of God - the

recovery of the

dumb, the deaf and

the blind is given

as an example "und

ihre Stärke ist

auch der Engel

Chor nicht mächtig

auszusprechen" ("and

�Thy strength is

such that even the

angel choir is not

powerful enough to

express it").

No. 4 is a quite

special aria, in

which the way it is

written down is a

little enigmatic.

Next to the alto

solo part Bach only

stipulates “organo“

and “basso

continuo“, with the

organ part written

on one stave (with

the bass clef!) and

the basso continuo

on another stave,

also with the bass

clef. Both parts

regularly cross each

other, which (if the

organist is playing

both parts)

requires two manuals

and still may be

expected to sound

rather confused. The

organo part (played

with the left hand,

in accordance with

the notation) has a

continuous,

virtuosic free fi

guration - it could

well be taken as a

description of God‘s

inextinguishable

works ("Gott

hat alles wohl

gemacht",

etc. "God

has made everything

well"

etc.). The continuo

part supports the

harmony quite simply

and shortly with

crotchets, and is

undoubtedly to be

played by the bass

string alone.

Because it was so

unusual to play a

whole solo piece

with only one hand,

our organist, Ewald

Demeyere, has put

forward the

hypothesis that

perhaps the

intention was for

the right hand to

play continuo, while

the left hand takes

on the solo part.

There is nothing to

disprove this theory

(there are countless

examples of

unfigured bass parts

which nevertheless

must be filled out

with harmonies) -

and it has the great

advantage of

creating a 'plausible',

complete organ part,

and thus making the

aria sound even more

festive.

The first part of

the Cantata ends

with this unique

piece.

The second part

(“seconda parte“,

i.e. after the

sermon) opens again

with a “Sinfonia“.

This is undoubtedly

the third movement

of the missing "concerto

original", a lively

Presto in 3/8 time,

in which the strings

and the woodwind

frame the virtuoso

organ part with

simple accompanying

figures.

�The secco

recitative "Ach,

starker Gott"

etc. ("Ah!

Mighty God", etc.)

follows after this.

The poet continues

to meditate on God‘s

miracles: "...so

kann ich dich

vernügt in meine

Seele senken

lassen",

"...damit

ich ... mich als

Kind und Erb

erweise"

("...thus

can I let my soul

find happiness with

Thee", "...as

it will turn out to

be with me, my

children and their

children").

The Cantata ends

with a dance-like

aria (not far

removed from a "minuet"!):

"Ich

wünsche nur, bei

Gott zu leben /

Ach! Wäre doch die

Zeit schon da /

Ein fröhliches

Halleluja mit

allen Engeln

anzuheben"

etc. ("I

wish only to live

with God. Ah! If the

time were but here

to begin singing a

cheerful Alleluia

with all the angels"

etc.), where the

organ and solo voice

play happily with

frequent triplets.

The opening

instrumental

ritornello (with all

the woodwind and

strings) returns

twice between the

various sections of

text - slightly

varied and in

different keys - and

closes the work full

of happiness.

"Ihr,

die ihr euch von

Christo nennet" - BWV

164

(for

the 13th

Sunday after

Trinity)

This Cantata, for

the 13th Sunday

after Trinity, was

originally performed

in 1725 (26th

August).

Bach took the text

from the

‘Evangelisches

Andachts-Opffer‘

(1715) of Salomon

Franck. It is mainly

based on the Gospel

for that Sunday (St.

Luke ch. 10, v.

25-37), the story of

the Good Samaritan,

which Jesus used as

an answer to

reproach an

arrogant, pedantic

lawyer. The latter

came to Jesus to

tempt him with

questions ("What

shall I do to

inherit eternal

life?" and "Who is

then my neighbour?").

But Jesus turned the

questions back on

him, indicating that

he should live his

life according to

what was written in

the scriptures,

instead of asking

questions.

Sometimes Bach has

done without the

four-part opening

chorus when it

seemed to him that

the text was more

suited to a single

singer (thus, for

example, in ,"Ich

habe genug" ("I

have now enough")

BWV 82, and in many

other cantatas). In

this cantata as well

the first verse of

S. Franck is not set

for more than one

voice, but given to

the tenor alone,

accompanied purely

by strings. As a

result we are more

directly involved in

the contents of this

text - it is as if

we are encouraged by

God himself, as a

person (rather than

as if a ‘universal

moral statement‘ has

been made): "Ihr,

die ihr euch von

Christo nennet, /

Wo bleibet die

Barmherzigkeit /

Daran man Christi

Glieder kennet?"

("You,

who call yourselves

disciples of Christ,

/ Where rests the

compassion now, / By

which we recognise

our brothers in

Christ?").

The question is not

purely rhetorical –

it is difficult,

because we know how

true it is. The tone

of the piece is

moving and

polyphonically

complex - one can so

clearly see the

‘holy‘ crowd of the

“announcer“ as well

as the rather

confused feelings of

those addressed. G

minor is indeed the

ideal key in this

situation. The first

word "Ihr,

..."

is set on its own by

Bach again and

again, followed by a

falling interval of

a fifth, which

strengthens the

directness of the

salutation so much.

Such a chief motif

is, throughout the

whole piece, only

repeated imitatively

by the two violins

and the tenor -

really very

surprising, as it never

occurs in the viola

or the bass in this

five-part

contrapuntal web! It

results in an 'artificial‘

triple “salutation“.

Can one go so far as

to see in this the

“speaking“ Trinity?

The ternary metre of

the music (9/8) is

suited to every

expression - be it

pathetic or rather

gently moving as in

"Die

Herzen sollten

lieblich sein, ..."

("Your

hearts ought to be

loving, ...").

Note also the more

intensive structure

of the next verse "So

sind sie härter

als ein Stein"

("yet

they are harder than

stone").

�In the following

recitative the bass

speaks - as

representative of

the faithful who are

addressed directly.

He confesses how we

indeed hear the

words of Jesus, but

do not put them into

practice. In typical

Bach style the

paraphrase of the

Sermon on the Mount

"Die

mit Barmherzigkeit

den Nächsten hier

umfangen / Die

sollen vor Gericht

Barmherzigkeit

erlangen"

("Those

who embrace their

neighbours with

compassion / Will

obtain compassion

before the judgement

seat")

is not set ‘secco‘

but arioso, as a

“verdict“ of

universal value.

Then follows the

aria (no. 3) for

alto, two transverse

flutes and basso

continuo ,"Nur

durch Lieb' und

durch Erbarmen..."

("Only

through our love and

through our mercy...").

The text endorses

the "verdict" of

the Sermon on the

Mount. The trochaic

rhythm (long-short)

of the poem is bent

here by Bach into a

smooth, calm quaver

movement ("spondaic"

long/long foot).

This calm,

continuous pulse

starts in the basso

continuo - the

so-called

“andante-bass“ - and

clearly creates the

going, the

striding

(also, at the same

time, the gait of

the helpful

Samaritan). The

flutes and voice

float freely over

this firm bass with

flowing semiquaver

figures, in which,

with descending

scale fragments, the

movement certainly

indicates

‘obeisance‘; the

loving and helpful

attitude of the

Samaritan. These

figures follow and

‘embrace‘ each other

continually.

Occasionally the

basso continuo

allows itself to be

tempted into this

pattern. Notable and

touching is the way

that Bach allows the

opening melodic

phrase on "Samaritergleiche

Herzen"

("hearts

like those of the

Samaritan")

to be immediately

echoed twice by the

flutes, so that this

idea affects us even

more.

The tenor undertakes

the accompanied

recitative which is

now added. The

earnest Christian

will take the

foregoing lecture to

heart, and

passionately beg

�for the help of

God‘s love: "Ach,

schmelze doch

durch deinen

Liebsstrahl / des

kalten Herzens

Stahl"

("Ah!

Melt with the

burning rays of Thy

love / the cold

steel of my heart").

The strings

characterise and

colour this

declamation with

harmony full of

expression, and the

recitative closes

peacefully in arioso

fashion: "...So

wird in mir

verklärt dein

Ebenbild"

("so

in me Thy image will

be transfigured").

In the duet for

soprano and bass,

which follows here,

Bach once again

displays the

outstanding

inventiveness of his

textual treatment,

in that he even

allows the

compositional

process to

characterise the

ideas contained in

the text: "Händen,

die sich nicht

verschließen /

Wird der Himmel

aufgetan. / Augen,

die mitleidend

fließen / Sieht

der Heiland gnädig

an. / Herzen, die

nach Liebe streben

/ Will Gott selbst

sein Herze geben."

("To

hands, which are not

closed / Heaven will

open. / At eyes,

which weep with

compassion / the

Saviour will glance

with mercy. / To

hearts, which strive

for love / God will

even give his own

heart.").

The two-part

instrumental

introduction (the

flutes, oboes and

both violins playing

in unison, with

basso continuo) is a

strong imitative

execution of a theme

(put forward in the

upper voice) in

combination with its

own reflection

(answered

canonically in the

continuo after a

bar): i.e. all

intervals, which

rise in the

‘original subject‘,

fall by the same

amount in the

counter-subject (and

this quite literally

holds out from first

to last!). This

produces a visual

pattern in the score

and, for the ear, an

aural pattern, which

in itself has the

image of “opening,

open up“ in contrast

to the "Verschließens"

("closing"),

with which the text

starts. The

execution of these

lines which mirror

themselves continues

throughout the piece

with immense

artistry in varied

combinations, in

which the harmony,

astoundingly, stays

quite natural. The

second section of

the text is about "mitleidend

fließen" �("weeping

compassion").

Here Bach introduces

in the vocal part a

calm, flowing and

melodic movement

with smaller

intervals. This line

is initially

strictly

contrapuntal, and in

fact a canon at the

fourth (the bass

starts, and after

three bars the

soprano sings the

same line a fourth

higher); and over

that the high

instruments still

play the opening

theme! The third

section of text ("Herzen,

die nach Liebe

streben",

"to

hearts, which strive

for love"

etc.), on the other

hand, develops new

material in the

vocal parts: a

lovely flowing line,

which is also

treated canonically

(this time at the

third), during which

the instrumental

“mirror playing“

continues between

the melody

instruments and the

basso continuo.

Undoubtedly one must

suspect from this

canonical imitation

in the vocal parts

an interpretation of

the “Imitation“ -

the Imitation of the

Words of Christ, at

which the text is

constantly aimed.

Also in this

fragment the

composer has

distorted the

trochaic metric foot

of the poet to the

equal spondaic for

the “alla-breve“

bars, the tempo

preferred for

generations by

composers for

complex

counterpoint.

A simple Chorale,

based on the

mannerist text of

Elisabeth Creutziger

(1524!) closes this

Cantata: "Ertöt‘

uns durch dein

Güte / Erweck‘ uns

durch dein Gnad"

("Let

us die through Thy

loving-kindness /

Awaken us through

Thy grace").

"Wer

Dank opfert, der

preiset mich" - BWV

17

(for

the 14th

Sunday after

Trinity)

This

Cantata was probably

fi rst performed in

1726. It is

organised in two

parts (before and

after the sermon as

usual), in which

each part begins

with a quotation

from the Holy

Scriptures, which

then serves the

(still anonymous)

poet as a theme for

further refl

ections.

Thus the opening

text for the fi rst

part is taken from

Psalm 50 (v. 23): "Wer

Dank opfert, der

preiset mich, und

das ist der Weg,

dass ich ihm zeige

das Heil Gottes"

("Whoso

offers me thanks,

glorifies me, and

that is the way,

that I will show him

the Salvation of God").

The psalmist,

somewhat

confusingly, uses

the "ich"

form with a double

meaning: on the one

hand, as if God

himself is speaking

here ("Wer

Dank opfert, der

preiset mich"),

and, on the other

hand, as a separate

person ("und

das ist der Weg,

dass ich

ihm zeige das Heil

Gottes").

With this he wants

to reveal that the

way to God‘s

Salvation lies in

offering thanks to

God.

In the recitative

(no. 2) and in the

aria (no. 3) the

poet describes for

the first time, how,

basically, the whole

of creation ("Luft,

Wasser, Firmament

und Erden",

"Air,

water, firmament and

earth",

and every living

thing) must praise

God, because of the

"ungezählten

Gaben, die er ihr

in den Schoß

gelegt"

("the

countless gifts,

which He has placed

in her lap").

In the recitative he

paraphrases Psalm

19, v. 5 and, at the

beginning of the

aria, some phrases

from Psalm 36, v. 5

("Herr,

deine Güte reicht,

soweit der Himmel

ist, / Und deine

Wahrheit langt,

soweit die Wolken

gehen",

"Lord,

Thy goodness extends

as wide as heaven

is, and Thy truth

reaches as far as

the clouds").

Finally he comes to

the heart of his

thought: even more

should man glorify

and thank God.

This basic thought

dominates the second

part of the Cantata

text then. This (no.

4) also begins, as

already mentioned,

with a quotation

from Holy

Scriptures: the poet

takes as his “motto“

from St. Luke‘s

gospel (ch. 17, v.

11-19) the “story“

of the salvation of

the ten lepers, of

whom only one -

actually a ,"gentile", a

Samaritan - came

back, to give thanks

to his saviour

(Christ). Here the

thought arises (aria

no. 5), that man is

never sufficiently

conscious of how

many �gifts he

constantly receives

from the creation,

and that he ought

therefore to give

thanks continuously.

A recitative (no. 6)

follows, an “echo“

from the Epistle to

the Romans (ch. 14,

v.5) "...Lieb,

Fried,

Gerechtigkeit und

Freud in deinen

Geist / Sind

Schätz etc.", ("Love,

peace, righteousness

and joy in Thy Holy

Spirit / are

treasures etc.").

The Cantata libretto

ends with a verse

from the Chorale "Nun

lob, mein Seel,

den Herren"

("Now

praise the Lord, my

soul")

by J. Gramann, from

1530.

Bach has set this

Cantata for two

oboes (d‘amore),

strings and basso

continuo, with the

usual four "concert

performers" - soprano,

alto, tenor and

bass.

The first movement,

to a text from verse

23 of Psalm 50, has

a meticulous

structure. The basso

continuo of constant

running quavers

keeps on indicating

a climbing gesture

(the "offer",

no doubt!), during

which both upper

voices (violins

doubled by the

oboes) interweave

with each other by

means of an

imitative motif.

After 27 bars

(3x3x3!) of

instrumental

introduction the

tenor enters with

the first section of

text. His motif is a

fugue subject six

bars long, of which

the "head" (a

rising fourth) was

also one of the

building blocks of

the instrumental

introduction. This

tenor entry is

framed and somewhat

veiled by the first

violin and both

oboes, which then

fall silent shortly

after the entry of

the alto. With the

soprano entry all

the instruments

re-enter, in order

to double the

singers (up to that

point and for the

moment only three),

so to speak. With

the bass entry the

basso continuo

finally abandons

just its ostinato

rôle and joins in

with the bass in his

thematic statements.

This web, which is

now in four parts,

continues for twenty

bars, until, after a

clear “close“ in the

dominant key of E

major, the piece

takes a new

direction. The known

thematic material is

shortly treated anew

in varied vocal and

�instrumental duet

and trio

combinations, until

a fresh fugal

construction is put

in place from the

bass up, which, in

45 bars of highly

inventive

counterpoint, leads

us to the end of the

movement.

Bach used this

choral movement

again in his A major

Mass on the words

“Cum sancto spiritu

etc.“.

After the secco

recitative of the

alto (no. 2, see

above) sections of

the motif, which are

familiar to us from

the opening chorus,

ring out again in

the aria (no. 3).

The movement is set

for two violins,

soprano and basso

continuo. The text

sings of God‘s

goodness and truth.

The three upper

voices develop – in

continuous imitation

and changing forms

over the bass

(quasi-ostinato as

in the opening

chorus) – the

picture of the

Trinity, which hangs

over the earth. (?)

The tenor‘s secco

recitative (no. 4)

initiates the second

part ot the Cantata.

As mentioned above,

it is a literal

quotation from St.

Luke‘s gospel – it

undoubtedly reminds

us in its narrative

style of the

Evangelist in the

Passions or the

Oratorios.

The tenor aria (no.

5) "Welch

Übermaß der Güte

schenkst du mir"

("What

excess of goodness

Thou gives to me")

follows, with

strings and basso

continuo, whose main

theme is easy to

assimilate. It hangs

over a suggestive

bass figure, where

the interval of a

second is repeated 6

times in succession,

the picture of the

“excess“? The whole

aria speaks of a

wonderful feeling

for the abundance

and the gratitude,

as it befits

mankind.

In the last section

of text from the

hand of the poet and

the compiler

respectively, the

secco recitative

(no. 6) continues to

echo the Epistle of

Paul to the Romans

(see above). Here

God‘s gifts are

presented as the

method which God

uses for mankind ,"an

Leib und Seele

vollkommentlich zu

heilen"

("to

heal completely in

body and soul").

It is notable how

very appropriate the

flowing ‘arioso‘

movement is for "...sind

Ströme deiner

Gnad, die du auf

mich lässt fließen"

("are

rivers of Thy grace,

which Thou lets fl

ow over me"),

which returns once

again to "round

things off" in

the final words.

The

closing chorale "Wie

sich ein Vat‘r

erbarmet"

("As

a father has mercy",

from 1530) is set

here in triple time

– relatively rare,

which lends the song

a certain positive

folk character, even

if it contains refl

ective

afterthoughts. We

know the same

chorale verse with

the same melody from

the middle section

of the great Bach

Motet "Singet

dem Herrn ein

neues Lied"

("Sing

unto the Lord a new

song"),

though it is

performed there in

‘straight‘ metre by

the second choir.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation:

Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|