|

|

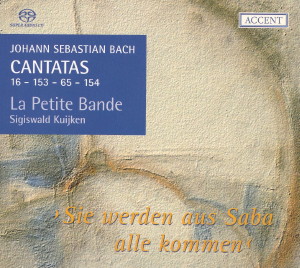

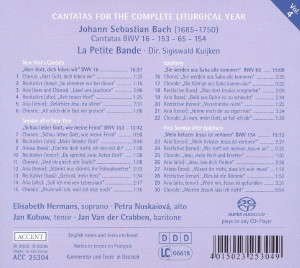

1 CD -

ACC 25304 - (p) 2006

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25304 - (p) 2006 - rectus

|

|

CANTATAS -

Volume 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New Year's Cantata

|

|

|

|

"Herr Got, dich

loben wir", BWV 16

|

|

16' 37" |

|

| -

Chorus: Herr Gott, dich loben

wir |

1'

33"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): So stimmen

wir |

1' 16" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass) & Chorus:

Lasst uns jauchzen, lasst uns freuen |

3' 46" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Ach treuer

Hort |

1' 25" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Geliebter

Jesu, du allein |

7' 31" |

|

|

| - Choral:

All solch dein Gut wir preisen |

1' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sunday after New Year |

|

|

|

| "Schau lieber

Gott, wie meine Feind, BWV 153 |

|

13' 42" |

|

| -

Choral: Schau lieber Gott,

wie meine feind |

0' 58" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Mein

liebster Gott |

0' 40" |

|

|

| -

Arioso (bass): Fürchte dich

nicht, ich bin mit dir |

1' 38" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Du

sprichst zwar, lieber Gott |

1' 38" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Und ob gleich alle

Teufel |

1' 08" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Stürmt nur,

stürmt, ihr Trübsalswetter |

2' 32" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Getrost,

mein Herz |

1' 34" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Soll ich meinen

Lebenslauf |

2' 17" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Drum will ich, weil

ich lebe noch |

1' 16" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Epiphany |

|

|

|

| "Sie werden aus

Saba alle kommen", BWV 65 |

|

15' 08" |

|

| -

Chorus: Sie werden aus Saba

alle kommen |

3' 35" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Die Kön'ge aus Saba

kamen dar |

0' 32" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Was dort

Jesaias vorhergesehn |

2' 00" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Gold aus Ophir

ist zu schlecht |

2' 44" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor):

Verschmähe nicht |

1' 23" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Nimm mich dir

zu eigen hin |

3' 34" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Ei nun, mein Gott, so

fall ich dir |

1' 20" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| First Sunday after

Epiphany |

|

|

|

| "Mein liebster

Jesus ist verloren", BWV 154 |

|

15' 12" |

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Mein liebster

Jesus ist verloren |

4' 13" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Wo treff

ich meinen Jesum an |

0' 35" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Jesu, mein Hort und

Erretter |

1' 07" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Jesu, lass dich

finden |

3' 36" |

|

|

| -

Arioso (bass): Wisset ihr nicht,

dass ich sein muß |

1' 10" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (tenor): Dies ist

die Stimme meines Freundes |

1' 52" |

|

|

| -

Duet (alto, tenor): Wohl mir,

Jesus ist gefunden |

3' 31" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Meinen Jesum laß ich

nicht |

0' 54" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Elisabeth

Hermans, soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| Jan

Kobow, tenor |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Sara Kuijken, violin

II

|

|

|

- Giulio D'Alessio,

violin II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Koji Takahashi, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Eve François, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Graham Nicholson,

horn |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe 1 and oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Yann Miriel, oboe

2 and oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Miniemenkerk,

Brussels (Belgium) - January 2006

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Eckhard

Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25304 - (1 CD) - durata 60'

39" - (p) 2006 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

Of

the four Cantatas

recorded here, the

first was performed

on New Year's Day

1726. The three

others all had their

first performances

in 1724 during the

first Christmas/New

Year's festival

which Bach spent as

Cantor in Leipzig.

This was an

extremely fruitful

period. Between

Christmas 1723 and

the 9th January 1724

Bach had composed

and performed for

the Leipzig faithful

no less than 9 works

for the church, of

which the last three

are presented in our

recording.

"Herr

Gott, dick loben

wir" - BWV 16

(New Year's Day

1726)

The libretto for

this cantata comes

from G. Chr. Lehms

(1711), and,

exceptionally, has

no connection with

the lessons for the

New Year.

The short opening

chorus (vivace)

is highly festive.

The instrumental

bass supports the

joyous dactylic

rhythm

(short-short-long),

continuously

repeated in a motif,

which goes on as an

ostinato to the end

of the piece. The

text of Luther's

translation of the

Latin Te Deum

is set here in a

lively three-voiced

texture for the

lower voices, over

which the soprano

sings the German "Te

Deum" with sustained

notes, doubled by

the "Corno

da caccia" (here

meant to sound like

the "Tromba da

tirarsi" [slide

trumpet]). The

strings and oboes

reinforce the

singers in vocal

passages; in other

places they play

independently to

intensify the

polyphonic web.

Bach could not deny

himself putting the

emphasis on the

concept of "eternity"

in this piece.

Shortly after the

soprano sings with

long note values the

section of text "Dick,

Gott Vater in

Ewigkeit" [Thee, God

Eternal Father], the

alto repeats the

same section twice

faster; on the other

hand, it is notable

that �the obbligato

figure dominating

the basso continuo

is twice as long. A

symbol of time

becoming eternal?

In the following recitativo

secco (bass),

the poet bids us to

sing our thanks

anew, and thus

introduces the aria

(no. 3). The bass

joins in the song ("Lasst

uns jauchzen,

lasst uns freuen")

[Let us rejoice, let

us be glad], and

everyone repeats his

appeal, supported by

the instruments

playing trumpet-like

figures. With the

words "Gottes

Güt'

und Treu",

etc. [God's goodness

and constancy], the

sound becomes more

tender and

transparent; in part

B of the text the

bass on his own

again takes up the

word ("Krönt

und segnet seine

Hand", etc.)

[If his hand crowns

and blesses]. Here

one notices the "visual"

madrigalism on "krönt";

a rapid ornamental

figure (already

announced first in

the violins) really

"crowns"

this syllable. This

figure will

illuminate

strikingly and

clearly several

times. After a

paraphrase of the

opening in A minor,

the piece returns to

C major at the end.

After this, the poet

directs our

attention to the

future. In the recitativo

secco for alto

God is beseeched to

continue "to

protect his church

and school"

and "to frustrate

Satan's evil

tricks" - and

we should put our

trust in him "for

evermore".

This profound trust

in God becomes more

intense in the

following aria (no.

5) in a veritable

and prolonged

declaration of love.

Over a steady and

simple andante in

the bass, the

obbligato solo

instrument (here a violetta)

develops a tender

and dancing line,

which resembles a

stylized polonaise.

The tenor makes his

entry with a gentle

flourish: "Geliebter

Jesu, du allein",

etc. [Beloved Jesu,

thou alone], and an

intense dialogue

develops, with

questions and

answers and combined

statements. Part B

of the text �goes

back explicitly from

the end to the da

capo "A",

thus describing in

fact an eternal

circle.

The closing chorale

(no. 6) to a text by

Paul Eber (c1580)

did not appear in

the original

libretto - Bach

added this communal

entreaty to conclude

this festive

cantata.

"Schau,

lieber

Gott, wie meine

Feind" - BWV 153

(For the Sunday

after New Year's

Day, 2nd January

1724)

This anonymous

cantata text

skilfully combines

the themes from two

Sunday lessons (the

Massacre of the

Innocents and the

Flight into Egypt).

After the short

opening chorale (by

D. Denicke, 1646),

begging for God's

mercy and help, the

poet allows an

almost theatrical

picture to emerge in

the following

sections of the

text.

- In the recitativo

secco (no.

2) man makes his

entrance,

surrounded and

threatened "by

dragons and

lions", and

implores God for

his help.

- In the Arioso

(no. 3), God

replies: "Fear

not, I am beside

thee".

- The

threatened man

is certainly

reassured by

these words, but

they are not

enough, so great

is his distress

and fear recitativo

secco (no.

4).

- The

Innocents'

community now

comes to help

him, and he

recalls God's

promise to him:

he will not

retreat from the

devil (no. 5) chorale

to a text by P.

Gerhardt, 1656).

- With

this, the man,

consoled,

rejoices and

expresses his

joy in an aria,

suddenly very

confident: with

God's help I

will be

protected from

all storms and

catastrophies!

- With this

emotional

outburst, the

consoled man is

calmer, and

reflects

further: endure

thy pain, Jesus

had to suffer

worse from the

beginning,

console thyself

with Him, suffer

with Him and�He will

summon thee to

the Kingdom of

Heaven

recitativo secco

(no. 7).

- The

man, so full of

despair until

now, is

completely

comforted and

sings God's

praise with

unconditional

confidence (Aria

no. 8). The

hardships of his

life will lead

him to Heaven.

After

this succession of

vivid ideas, the

cantata ends

symmetrically with a

chorale of three

verses (by Martin

Moller, 1587), which

sings once again by

way of summary about

life under Christ's

protection.

A few comments on

the individual

numbers:

The text of the

Arioso (no. 3) "Fürchte

dich

nicht" etc. is a

quotation from

Isaiah (Ch. 41, v.

10). Although this

prose text is

obviously not ruled

by any regular verse

metre, Bach sets it

in a brisk triple

time. The main motif

in the introduction

for basso continuo "announces"

quite recognizably

the rhythm of the

words in the first

four notes. This

motif becomes the

permanent leitmotif

of the whole

fragment; thus Bach

illustrates the

ever-present comfort

of God: "Fear

not, I am beside

thee".

In the tenor

recitative (no. 4),

it is notable how

Bach colours the

text with a striking

madrigalism; thus,

for example, on "Bogen"

[bows] (the form of

the melismas is a

lively bowed line),

and also for "sie

richten ihre

Pfeile" [they

aim their arrows],

where the rising

interval of a second

conveys a picture of

the released arrow.

On "sterben"

[die], the melody

and harmony are

clearly chromatic

and plaintive, and

for "hilf,

Helfer" [help,

Helper] the repeated

imitation of the

sung motif in the

basso continuo is an

intensification and

strengthening of the

prayer ceaselessly

repeated by the

singer.

In the tenor Aria

(no. 6) a lively

dotted rhythm forms

the bass part above

which there are

rapid runs, which

sometimes - with the

soloist as well -

are presented in

unison. In this way

Bach is able to

describe the storm

and the "Fluten"

[billows], which are

the subject of the

text, as well as the

"Unglücksflammen"

[flames of woe]; and

finally (at the end)

the "Erretter"

[redeemer] Himself.

Is God not as

powerful in His

actions...? "Ruh"

[peace] is on a long

sustained note (as

if one had to wait

for it), which ends

on a dissonant chord

with a fermata.

(This peace is not

in any way final).

The recitativo secco

(no. 7) first of all

goes back to a

highly emotional

telling of the

gospel story of the

Massacre of the

Children in

Bethlehem and the

Flight into Egypt

(note particularly

the treatment of the

word "Flüchtling"

[one who flees]).

Then follow, in

strong contrast to

the foregoing, the

resigned decision "Wohlan,

mit Jesu tröste

dich" [Come,

with Jesu be thou

comforted] etc., and

the through-composed

"Andante"

on the words "Denjenigen,

die hier mit

Christo Leiden /

will er das

Himmelreich

bescheiden"

[Those who suffer

here, like Christ,

they will be

summoned by him to

the Kingdom of

Heaven]. Here

reappear the

instrumental bass

and the vocal line,

as if bound in

dialogue with mutual

imitation - symbol

of union, of

solidarity?

The chief idea of

the alto aria (no.

8) is the afterlife

in Heaven, compared

to the suffering of

life on earth. A

tremendous kind of

noble and restrained

dance music is heard

(is this Heaven?);

even the "lauter

Jubilieren"

[resounding

jubilation] in verse

4 is not

particularly

emphasized; the

trochaic metre

(long-short)

presents quite

naturally a tempo of

a kind of court

minuet. For the

words "Daselbsten

verwechselt

mein Jesu

das Leiden

mit seliger

Wonne"

[There will my Jesus

change sorrow into

blessed joy] the

poet "changes"

the metre very

rapidly (from

Trochaic to

Dactylic). Bach

reacts to this

process with a new

motif in the treble

(at a somewhat

heightened tempo, "Allegro"),

which is immediately

taken up by �the

basso continuo and

the first violins,

and leads to a long

vocalise on the

final word "Freuden"

[joy]. The postlude

brings us back to

the opening theme,

but now with a

greater swing; the

heavenly life?

Exceptionally, this

cantata makes no use

of wind instruments.

"Sie

werden aus Saba

alle kommen" - BWV

65

(For the Feast of

Epiphany, 6th

January 1724)

The Gospel according

to St. Matthew about

the Kings from the

East seeking to

worship the newborn

Christ Child

inspired Bach to

write one of his

most attractive and

colourful cantatas.

The poet of the

text, who is still

unknown, opens his

work with a literal

quotation from the

book of Isaiah (ch.

60 v. 6) "Sie

werden aus Saba

alle kommen, Gold

und Weihrauch

bringen und des

Herren Lob verkündigen"

[All they from Sheba

shall come: they

shall bring gold and

incense; and they

shall shew forth the

praises of the

Lord]. To illustrate

this theme, Bach had

recourse to a

colourful group of

wind instruments:

two "Corni

da caccia", two

recorders and two "Oboi

da caccia", as well

as the usual strings

with basso continuo.

The "Corni da

caccia" (hunting

horns) are smaller

than normal in this

cantata, and play

more in the trumpet

tessitura; similarly

the recorders are

played mostly in the

high register; so

the "Oboi da caccia"

are here the deepest

wind instruments

(often doubled with

the second violins

and the viola).

The entry of the

voices is preceded

by an instrumental

introduction of 8

bars, which

illustrates in an

almost lifelike way

the solemn

procession of the

Kings. The 12/8 time

signature of this

opening movement

contains within

itself the "binary"

of a slow march with

the "three-beat

swing" of many an

�elegant dance. The

high horns present

the principal motif

in two parts, which

the voices develop,

taken up directly by

the other wind

instruments and the

high strings. After

a short episode in

which the different

families of

instruments are

heard one after the

other, the principal

motif is played

solemnly by all of

them in unison, and

ends with several

voices. Then the

singers make

successive entries

with the principal

motif, and finally

unite in four parts,

supported by the

instruments. The

piece then develops

in various

combinations, until

a long fugue begins

in the bass (with a

new motif), which

leads the text to

the end. After the

four voices have

entered in the

fugue, the

instruments

reinforce each

subsequent entry of

the subject. After

the initial motif

has appeared in the

treble, the movement

closes with a

festive unison from

all the

participants.

Then follows, under

the title of "Chorale",

the fourth verse of

the hymn known as "Puer

natus in Bethlehem"

(1545), in German: "Die

Kön'ge

aus Saba kamen

dar" [The

kings came there

from Sheba].

In the recitativo

secco (no. 3)

for bass the poet

tells the story

quite briefly of

what happened in

Bethlehem, and

places the events in

relation to his own

life: how the Three

Wise Men "muss

ich mich auch zu

deiner Krippen

kehren / und

gleichfalls

dankbar sein"

[I must also seek

Thy crib, and

likewise give my

thanks], and the

most precious gift I

could make is my

heart. The sudden

chromatic colouring

in the harmony on "zu

Bethlehem im

Stall" [in

Bethlehem in a

stable] is

remarkable,

undoubtedly an

allusion to the

difficult

circumstances of the

birth of Jesus. In

addition, the "Lebensfürst"

[Prince of life] is

particularly

coloured, and the

final sentence "so

nimm es gnädig

an / weil

ich nichts Edlers

bringen kann"

[so accept it

graciously, for I

can bring nothing

more precious] the secco

declamation changes

into a "precious"

arioso.

�The aria (no. 4)

for bass, 2 Oboi da

caccia and basso

continuo builds

further on this

idea: "Gold

aus Ofir ist zu

schlecht / Weg,

nur weg mit eitlen

Gaben" [Gold

from Ophir is too

poor, go away, just

go with such vain

gifts]. In the Old

Testament it is told

how King Solomon

brought much gold

from the land of

Ophir - this shows

us how vain such a

gift would be: "Jesus

will das Herze

haben" [Jesus

wants your heart],

and nothing else.

The two wind

instruments and the

basso continuo

continuously imitate

the prosody of the

opening of the text

"Gold

aus Ofir ist zu

schlecht";

through this

repetition one can

almost see how the

gold is brought step

by step. The same

rhythmic motif comes

later on the words "weg,

nur weg mit eitlen

Gaben" and

also on "Schenke

dies, O

Christenschar"

[Offer this, O

Christians all].

Characteristic also

is the extremely

long vocalise on "eitle

Gaben": how

better could Bach

have illustrated

vanity?

The tenor's recitativo

secco (no. 5)

addresses God with

the plea not to

reject his heart and

all that it contains

(the gifts of faith,

of prayer and of

patience are here

compared to gold,

incense and myrrh).

The poet, however,

goes even further,

and asks directly

that God should give

himself to him.

The virtuoso aria

(no. 6), with which

this recitative

ends, uses once more

the rich sonority of

the entire

instrumental

ensemble, which

again is

occasionally laid

out in "families".

In a sort of rondo,

the tenor sings of

the total

abandonment of his

heart to God; the

rich vocalise on "Alles,

was ich bin"

[All that I am]

illustrates very

clearly this theme

of the text.

Although in the main

source for this

cantata (Bach's

autograph score)

there is no text for

the concluding

chorale,

traditionally the

10th verse of the

song "Ich

habe in Gottes Herz

und Sinn" by Paul

Gerhardt (1647) is

used, which follows

on well from the

aria.

"Mein

liebster Jesus 1st

verloren" - BWV

154

(For the first

Sunday after

Epiphany, 9th

January 1724)

The text of this

cantata, of unknown

origin, follows the

gospel reading for

Sunday (St. Luke,

ch. 2, v. 41-52), in

which it is told how

the 12-year-old

Jesus stayed

unnoticed among the

scribes in

Jerusalem, while his

parents, suspecting

nothing, returned to

Nazareth after the

Passover. When they

could not find him

among their

kinsfolk, they

returned to

Jerusalem, and found

him among this noble

company, listening

and asking

questions.

The poet considers

this famous episode

in the life of Jesus

from the perspective

of his own spiritual

life, personifying,

as it were, the

whole Christian

community, and

speaking in its

name.

Beginning "ex

abrupto" with the

plaintive cry "Mein

liebster Jesus ist

verloren / O

Wort, das mir

Verzweiflung

bringt" [My

dearest Jesus is

lost, O

Word, that brings me

to despair] etc.,

significantly, this

text is not

presented by a vocal

quartet, but only by

a soloist as a

passionate "personal"

lament (aria for

tenor and strings).

Bach's composition

reminds us of a

passacaglia. The

repeated bass figure

is strongly

chromatic, and, with

its many pauses, has

a kind of "hesitant"

character (one can

already see here the

vain "search").

The first violin

introduces the

strongly dotted

principal motif,

with its plaintive

appoggiaturas. The

tenor repeats it

then, interrupted by

uneasy isolated

figures on the

violins. For "O

Schwert, das durch

die Seele dringt"

[O

sword which pierces

my soul] Bach

depicts the piercing

and cutting movement

in the violins and

the viola. "Donnerwort"

[word of doom] is

illustrated by

repeated notes.

In the following recitativo

secco the poet

asks pathetically

where can he find

his Jesus, and

indicates once again

how hard he feels

the loss. The tenor

sings this passage

almost as an

extension of his

aria.

After this the

community (in the "chorale",

no. 3) sing out

about the extent all

hearts long for

their "little

Jesus" (text by

Martin Jahn, 161).

This chorale is a

smooth transition to

the next aria, which

is almost a kind of

lullaby! The

beautiful naive text

"Jesu,

lass dich finden /

lass doch meine Sünden

/ Keine dicke

Wolken sein / wo

du dich zum

Schrekken / willst

für

mich verstekken /

Stelle dich bald

wieder ein!"

[Jesu, reveal

thyself, let not my

sins be a thick

cloud where, in

order to scare me,

thou concealest

thyself. Come back

soon!] is sung by

the alto,

accompanied by two

Oboi d'amore and (in

place of a basso

continuo) by a "Bassetto",

an octave higher, of

violins and viola in

unison. The whole

gives a Christmas

feeling; only on the

words "Schrecken"

and "verstecken"

a brief dissonance

appears.

In the following

bass aria Jesus'

sobering answer to

this prayer comes

quite unexpectedly

and directly, for

the poet quotes

literally from the

gospel according to

St. Luke (ch. 2, v.

49): "Wisset

ihr nicht, dass

ich sein muss in

dem was meines

Vaters ist?"

[Wist ye not that I

must be about my

Father's business?]

This piece is a

purely monothematic

duet, in which the

basso continuo and

the singer are

entwined with each

other in an

imitative style. An

announcement of the

text's message?

At this reply from

Jesus, the believer

jumps with joy:

Jesus has returned!

The significance of

Jesus' words also

becomes clear to him

as a result, and he

now "instructs"

his own soul in what

he has understood;

just as Jesus went

to his Father in the

temple, so must

thou, my soul, seek

God the Father there

recitative (no. 6),

tenor.

Now that

Jesus has been

found again and

his commandment

understood, the

Christian can

breathe again, and

from now on he

will "nimmermehr

lassen"

[nevermore leave]

and "beständig

umfassen"

[steadfastly

embrace] Jesus

through the

strenght of his

faith. That this

text (no. 8) was

conceived by Bach

as a duet, can

perhaps be

understood from

the preceding

recitative. We saw

there (according

to Baroque

imagery) how the

believer speaks to

his soul as a "second

person". Is this

duet, then, not

the

"continuation"

of the inner

dialogue, in

qhich the two

reach an

agreement and

sing of their

decision with

one voice?

This

duet sounds to

us like a

gavotte, gay

but

controlled. In

the first four

verses Bach

has switched

to a

quasi-binary

from the

trochaic metre

(long/short: "Wohl

mir, Jesus

ist gefunden",

etc.). At the

moment, in the

last two

verses, where

the poet

passes from

the trochaic

to the

dactylic

(long/short/short:

"Ich will

dich, mein Jesu,

nun nimmermehr

lassen"),

Bach changes

to a swinging

3/8

(passepied?).

The opening

ritornello of

the

instruments

(strings and 2

Oboi d'amore)

then concludes

the aria in

the initial

Gavotte tempo.

In

the closing

chorale (Chr.

Kaymann, 1658)

the community

confirms once

again: "Meinem

Jesum lass ich

nicht...

Selig, wer mit

mir so

spricht"

[I will not

leave my

Jesus...

Blessed is he

who, with me,

speaks thus].

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation:

Christopher

Cartwright and

Godwin Stewart

|

|