|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25303 - (p) 2005

|

|

1 CD -

ACC 25303 - (p) 2005 - rectus

|

|

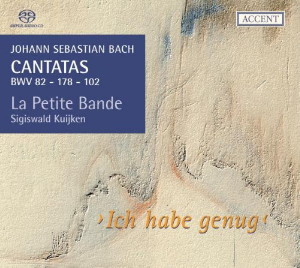

CANTATAS -

Volume 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

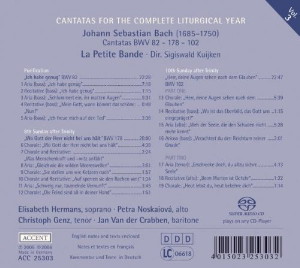

| Purification |

|

|

|

"Ich habe genug",

BWV 82

|

|

22' 28" |

|

| -

Aria (bass): Ich habe genug |

7'

18"

|

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Ich habe

genug! Mein Trost ist nur allein |

1' 15" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Schlummert ein,

ihr matten Augen |

9' 31" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Mein Gott!

Wann kömmt das schöne: Nun! |

0' 48" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass):

Ich freue mich auf meinen Tod |

3' 38" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8th Sunday after

Trinity |

|

|

|

| "Wo Gott der

Herr nicht bei uns hält", BWV

178 |

|

20' 00" |

|

| -

Choral: Wo Gott der Herr

nicht bei uns halt |

4' 38" |

|

|

| -

Recitative & Choral

(alto): Was Menschenkraft und -witz

anfäht |

2' 24" |

|

|

| -

Aria (bass): Gleichwie die

wilden Meereswellen |

3' 51" |

|

|

| -

Choral (tenor): Sie stellen

uns wie Ketzern nach |

1' 57" |

|

|

| -

Choral & Recitative

(alto, tenor, bass): Auf sperren sie

den Rachen weit |

1' 34" |

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Schweig,

schweig nur, taumelnde Vernunft |

3' 45" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Die Feinde sind all

in deiner Hand |

1' 51" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10td Sunday after

Trinity

|

|

|

|

| "Herr, deine

Augen sehen nach dem Glauben",

BWV 102 |

|

22' 47" |

|

| Part one |

|

|

|

| -

Choral: Herr, deine Augen

sehen nach dem Glauben |

5' 39" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (bass): Wo ist das

Ebenbild, das Gott uns eingepräget |

1' 15" |

|

|

| -

Aria (alto): Weh der Seele,

die den Schaden nicht mehr kennt |

5' 28" |

|

|

| -

Arioso (bass): Verachtest du

den Reichtum seiner Gnade |

3' 01" |

|

|

| Part two |

|

|

|

| -

Aria (tenor): Erschrecke doch,

du allzu sechre Seele |

4' 13" |

|

|

| -

Recitative (alto): Beim

Warten ist Gefahr |

1' 22" |

|

|

| -

Choral: Heut lebst du, heut

bekehre dich |

1' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Elisabeth

Hermans, soprano |

LA PETITE BANDE

/ Sigiswald

Kuijken, Direction |

|

| Petra Noskaiová,

alto |

- Sigiswald

Kuijken, violin I |

|

| Christoph Genz,

tenor |

- Katharina Wulf, violin

I

|

|

| Jan Van der

Crabben, bass |

- Sara Kuijken, violin

II

|

|

|

- Giulio D'Alessio,

violin II |

|

|

- Marleen Thiers, viola |

|

|

- Koji Takahashi, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Eve François, basse

de violon |

|

|

- Graham Nicholson,

horn |

|

|

- Patrick

Beaugiraud, oboe 1 and oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Yann Miriel, oboe

2 and oboe d'amore

|

|

|

- Ewald Demeyere, organ |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Predikherenkerk,

Leuven (Belgium) - September 2005

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Staff |

|

Tonstudio

Teije van Geest, Sandhausen

(Germany) | Tonstudio van Geest |

E. Steiger |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

ACCENT

- ACC 25303 - (1 CD) - durata 65'

15" - (p) 2005 (c) 2006 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

COMMENTARY

on

the cantatas

presented here

"Ich

habe genug"- BWV82

(for Candlemas,

February 2, 1727)

This is one of the

best known and most

popular Bach

cantatas; for

practical reasons,

it has been inserted

at this point in our

series of

recordings, instead

of in strict

liturgical order.

The cantata for the

9th Sunday after

Trinity (BWV 168:

"Tue Rechnung,

Donnerwort") will be

included in a later

compilation. We beg

your forbearance.

The librettist of

this cantata is

again unknown; by

way of exception,

the texts are all

new, containing

neither chorales nor

biblical passages.

The Candlemas

service includes a

reading from the

Gospel according to

St Luke (2.22-23).

Those words are the

starting point of

the cantata text.

The scene is the

temple in Jerusalem.

After the prescribed

time, Maria and her

child are brought

there, Maria to

undergo the ritual

cleansing after the

birth of her first

son, Jesus to be

circumcised (for the

sake of simplicity,

Luke has both

rituals take place

on same day). The

old man Simeon also

comes to the temple;

the Holy Spirit has

revealed to him that

he shall not die

before he has seen

the Lord's Anointed

with his own eyes.

And so it is; Simeon

recognizes the

Saviour in the

child, takes it up

into his arms and

says: "Nun lassest

Du, Herr, deinen

Diener in Frieden

gehen nach deinem

Wort..." (Lord, now

lettest thou thy

servant depart in

peace, according to

thy word...).

Those are the

"facts" on which the

librettist builds;

he takes Simeon as a

model for believers:

just �as Simeon can

welcome death after

his profound

recognition of

Christ, so shall the

believer as well.

Bach entrusted the

entire text to a

single singer - a

bass. He undoubtedly

begins by depicting

the old Simeon, but

it gradually comes

to seem as if he is

bringing the devout

listener himself

into the whole

monologue.

The cantata begins

with an aria in 3/8

time; the string

bass and viola

playing in octaves

produce a constantly

rocking rhythm of

three gently

repeated quavers. At

the same time, the

violins produce a

lightly swinging

semiquaver motion in

horizontal lines;

then the oboe enters

with the motif we

later identify in

the text as "Ich

habe genug" (I have

had enough) - a

melodic drawing that

recalls passages

like "Erbarme dich"

in the St Matthew

Passion. Lyrical

ornamental

variations

characterize the

rest of the oboe

part, into which the

solo singer then

creeps as it were.

Bach elegantly

steers the original

(rather dynamic) dactylic

metre (long, short

short / etc.) into triple

time,

imparting peacefully

moving impetus to

the music; does one

not almost see

the old man cradle

the child in his

arms while he

expresses his

realization? The C

minor key helps us

to experience the

serious "affection"

of this aria, while

the attractive

melisma on the word

"Freude" comes as a

surprise both times.

It is helpful to

read the richly

evocative text of

this aria quietly to

oneself before

listening; that

enables us to feel,

for example, how

very effectively the

opening verse "Ich

habe genug" returns

in the middle of the

aria and again at

the end. (It should

be noted that in our

version we

deliberately

normalize the

written form "genung"

to "genug" -

both forms were

current at the time,

but we have

preferred the more

familiar one.)

�The ensuing

recitative once

again begins and

ends with the verse

"Ich habe genug".

The librettist now

clearly speaks on

behalf of the

believer, of the

"new" Simeon. Like

Simeon in the

gospel, he

passionately longs

for his departure

from this world

after the mystical

union with God. As

usual, Bach treats

the text carefully;

for example, the

verse "Lasst uns mit

diesem Manne ziehen"

(let us go with this

man) is set in a

regularly striding

andante and not in

the free, secco

style of the other

verses, and

"Freuden" (joy) is

given a striking

cliché; the

summarizing, final

"Ich habe genug" is

also set in arioso

style and is brought

to a close by the

basso continuo.

The ensuing aria

"Schlummert ein, ihr

matten Augen, /

Fallet sanft and

selig zu" (fall

asleep now, ye weary

eyes, / close gently

and in bliss) is a

"slumber aria", a sommeil

as the French called

it. Such arias are

found in countless

secular cantatas and

operas of the

Baroque - always

moments of pure

aesthetic enjoyment.

The librettist and

Bach finally

transcend that

tradition in this

slumber aria, for "falling

asleep"

here stands for

leaving this world;

the music (so it

seems) arises

directly from the

mystical longing.

The oboe da caccia

and two first

violins in unison

sound bewitching;

the constantly

peaceful pulse of

the bass line makes

time palpable, is

the course of time

that flows under

everything. The trochaic

metre of the text

(long-short) is

retained throughout

in the music and

here brings calm and

peace. Protracted

notes, distributed

among all four

(sometimes five)

voices, including

the vocal part,

illustrate sleep. At

"Welt, ich bleibe

nicht mehr hier"

(world, I shall no

longer stay here),

the music takes on

some passion and

restlessness; the

singer is here

accompanied only by

the striding basso

continuo until he

returns to his

opening words

"Schlummert ein...",

when the other

instruments again

join in. The same

treat�ment is given

to the section "Hier

muss ich das Elend

bauen..." (here I

must live in

misery...), except

for the final word

"Ruh" (peace) on a

long note, where the

higher instruments

twice alternate

briefly with the

basso continuo; the

constant pulse is

interrupted here,

only to be taken up

again and continued

to the end. The

frequent fermatas

(sometimes at

unresolved

dissonances) further

deepen the textual

expression; the

quiet after the

fermatas perhaps

"speaks" even more

than the notes.

In the short

recitative "Mein

Gott! Wenn kömmt

das schöne:

Nun!" (my God! when

will that sweet

"now!" come?), the

impatience of the

librettist for the

hereafter makes

itself felt for the

last time. He

resolutely ends with

the words "Der

Abschied ist gemacht

/ Welt, gute Nacht"

(the parting is made

/ good night world).

Bach's music closely

follows the words

and images; the

voice sinks low at

"Erde" (i.e. the

grave) and soars

upward at "dart bei

dir im Schosse"

(there in your bosom

- i.e. heaven).

"Welt, gute Nacht"

is marked adagio

and arioso;

the melodic line of

the basso continuo

depicts the parting

and the going;

at "Nacht" (night)

Bach sets a

deceptive cadence,

which colours the

word wonderfully and

evokes the

unresolved mystery.

The final cadence is

then performed by

the continuo

instruments alone.

After this plunge

into profundity, the

closing aria

(Vivace) "Ich freue

mich auf meinen Tod"

(I look forward to

my death) brings us

a foretaste of the

eternal joys in

accordance with the

Christian world

view. The fast,

dance-like music is

of rousing energy

and impetus, with

abrupt accents and

interruptions; it

would have been just

as appropriate and

charming in

unchanged form in a

"secular" cantata -

Bach's art clearly

does not

make the rather

embarrassing

distinction between

"secular" and

"sacred" to which we

have become

accustomed.

"Wo Gott der Herr

nicht bei uns hält"-

BWV 178

(8th Sunday after

Trinity)

This chorale cantata

of 1724 (July 30)

uses a poetic

rendering of the

text of Psalm 124

made by Justus Jonas

in 1524 (see Dürr,

p. 513); an

anonymous librettist

from Bach's time

adopted six of the

eight stanzas of the

original chorale

literally (sometimes

with interjections

of his own); he

expressed the

content of the other

two in his own words

(arias 3 and 6). The

central theme is

God's power over the

enemies of

Christians - and how

Christians should

therefore believe in

God and love him.

The work begins with

the chorus "Wo Gott

der Herr nicht bei

uns hält"

(when the Lord God

does not stand with

us), throughout

which the

instruments combine

a constantly dotted

rhythm with a faster

figure. Over that

conflict-ridden

fabric (enmity and

dispute), the vocal

ensemble then sings

the simple chorale

setting, initially

in its basic form,

in clearly separated

"blocks"; but not

all the blocks are

in such a simple

form: depending on

the requirements of

the text, the three

lower parts

sometimes take part

in the fast and

vigorous activity of

the instruments -

for example, at the

words "wenn unsre

Feinde toben" (when

our foes are

raging), when the

soprano alone

carries the original

chorale tune,

supported by a

"corno".

That powerful

movement is followed

by a recitative for

alto with basso

continuo, in which

Bach follows the

textual structure in

a masterly way. Here

the Baroque

librettist inserted

between the seven

verses of the second

stanza of Justus

Jonas's original

chorale four

"blocks" of his own

verse, and we

perceive how Bach

indeed set those new

fragments in a

clearly different

manner. The old

verses of 1524 are

treated strictly in

the old contrapuntal

manner; while the

alto sings each

motif of the chorale

verse, the bass line

repeats the same

motif at four times

the speed and �at

various pitches.

This proportional

procedure is

directly perceptible

and sounds strangely

disconcerting,

archaic and a little

"theoretical" to us.

The "new verses", on

the other hand, are

set in the

contemporary Baroque

secco-recitative

style, which starkly

differentiates them

from the older

verses. Bach often

applied this method

of working at

similarly structured

places in other

cantatas.

Next comes a "free"

aria. As has been

mentioned, Bach's

librettist freely

adapted this third

stanza of the

chorale, and Bach's

writing is here

completely freed

from the old

material. The bass

soloist, led,

driven, framed by

the unison violins

on one hand and by

the basso continuo

on the other,

graphically depicts

the very Baroque

text: "Gleichwie die

wilden Meereswellen

/ mit Ungestüm

ein Schiff

zerschellen / so

raset auch der

Feinde Wut / und

raubt das beste

Seelengut..." (just

as the wild ocean

waves / impetuously

a ship will shatter,

/ so too rages the

foe's wrath / and

ravages the best of

souls...). The three

parts (violins, bass

soloist and basso

continuo) depict the

movement of the

waves and the

"Christi Schifflein"

(little boat of

Christ) in their

endless alternation.

Naive art?

Essentially, yes -

but how ably and in

what a complex

manner it is

realized!!

Two oboes d'amore

and basso continuo

weave the dense

fabric over which

the tenor now openly

and quite without

ornament performs

the fourth chorale

stanza in its

original form: "Sie

stellen uns wie

Ketzern nach..."

(they pursue us like

heretics...). The

three instrumental

parts run after each

other in constant

imitation - like the

motion of a hunt. On

the other hand, Bach

here conjures up a

most complicated

compositional

process from a

perhaps naive basic

idea.

The next movement

(5) is formally

analogous to the

second movement - a

recitative on two

"levels", �with the

old chorale text

(this time in simple

homophonic,

four-part form in

various blocks) and

"new" (mostly short)

textual insertions

set in solo

recitative style.

The special

characteristic of

this fragment,

however, is the

unceasing

instrumental basso

ostinato, which

repeats a rising

triadic motif 52

times in succession

and is probably

intended to

illustrate "Auf

sperren sie den

Rachen welt" (they

open their hungry

maws wide) at the

beginning of the

text and to keep on

reminding us of it.

In the 6th verse of

this chorale stanza,

at the words "Und stürzen

ihre falsche Lahr"

(and bring to naught

their false

teachings), Bach

ventures to

harmonize the last

three syllables in

an absolutely

unorthodox manner:

the "false

teachings" are set

as a striking

deception!

The ensuing aria (6)

uses the Baroque

librettist's

rendering of the

sixth stanza of the

old chorale, this

time for tenor and

strings: "Schweig,

schweig nur,

taumelnde Vernunft /

Sprich nicht: die

Frommen sind

verloren..." (hush,

hush then, reeling

reason / say not:

the pious are

lost...). The

soloist's imperious

"Schweig" is

impetuously repeated

32 times; Bach

depicts the

"taumeln" (reeling)

in a long falling

scale figure, while

he almost always

gives "Vernunft"

(reason) a proudly

rising interval.

This decidedly

"constructed"

chorale cantata

concludes with the

last two stanzas (7

and 8) of the old

chorale, set simply

in four parts.

"Herr, deine

Augen sehen nach

dem Glauben" - BWV

102

(10th Sunday

after Trinity)

This is a

large-scale cantata

in two parts and

complex in

structure. It was

performed for the

first time on August

25, 1726 and was

probably presented

again under Bach's

direction in about

1737.

The first part

begins with a

fragment from the

Old Testament

(Jeremiah 5.3),

which shows the

peo�ple's

stubbornness in

reference to God's

actions and council;

it concludes (4)

with a fragment from

Paul's Epistle to

the Romans (2.4-5),

which in essence

links up with it.

These two fragments

are thus prose

texts, while all

others are

poetically

constructed texts,

as usual. The writer

of the recitatives

and arias is

unknown, but the

closing chorale

consists of two

stanzas of a chorale

by Johann Heermann

of 1630.

The central theme of

the cantata is (the

lack of) penitence;

the librettist uses

Baroque contrasts to

depict the causes

and consequences of

our indifference

towards God's grace.

The opening movement

is impressively

effective and of

complex conception.

To begin with, the

instruments (oboes,

strings, basso

continuo) introduce

the main motivic

material in a

magnificent

dialogical

introduction.

Supported by an

isolated collective

exclamation of

"Herr" (Lord), the

alto and soprano

then alternate with

interventions by the

complete vocal and

instrumental

ensemble, until at

the words "Du schlägest

sie, du plagest sie"

(thou hast stricken

them, thou hast

tormented them) a

new motif announces

itself (the

"striking" is

depicted in staccato

notes). It is later

developed in a

transparent fugato

passage in which the

strings are silent

for the first time.

Then comes the

section "Sie haben

ein härter

Angesicht wie ein

Fels, und wollen

sich nicht bekehren"

(they have faces

harder than rock and

do not want to

convert). Bach sets

it fugally, using a

new theme which

lends the word

"Fels" (rock) almost

visual emphasis by

repeatedly

presenting it on a

rising tritone

(augmented fourth) -

the diabolus in

musica! This

fragment returns

without a break to

the beginning of the

text and the

corresponding

motivic material.

The opening chorus

then closes with

this quasi da capo -

but not without a

number of heightened

additional effects

(for example, the

uniquely dissonant

and syncopal

exclamation at

"Herr" in bar 112).

An impassioned

recitative secco for

the bass questions

our position vis-à-vis

God - no wonder that

He "gives in to the

heart's conceit" of

the obdurate sinner.

There follows a kind

of lamento aria for

alto, oboe and basso

continuo. The key (F

minor) was even then

(1726) the usual one

to depict the

underworld, the

damned, the eternal

lament. The text

begins with the

words "Weh der

Seele, die den

Schaden nicht mehr

kennt / und, die

Straf auf sich zu

laden, störrig

rennt" (woe to the

spirit which its

disadvantage no

longer knows, / and,

calling judgement

down upon itself, /

stubbornly runs).

The voice begins its

lament with a long

and dissonant "Weh",

which finally

descends into a

lower dissonance

before resolving

briefly. The piece

is a pure trio

movement, in which

the two upper parts

(oboe and alto)

perpetually float

over an almost sadly

striding, calm bass

line.

At the point where

another recitative

might be expected,

Bach surprisingly

continues with a

section headed

"Arioso" (4) in 3/8

time that is

introduced by the

strings. This string

introduction

anticipates the

impatience and

vehemence of the

words "Verachtest du

den Reichtum seiner

Gnaden..."

(despisest thou the

riches of his

goodness...) from

the Epistle to the

Romans, which are

soon taken up by the

bass. A rising

seventh

characterizes the

beginning of each

section of this

prose fragment at

"Verachtest du",

"Weissest du nicht"

and "Du aber...". It

repeats in triple

time equally

stressed identical

figures in the

sentence "Du aber

nach deinem

verstockten

und unbussfertigen

Herzen

häufest

dir selbst

den Zorn auf

den Tag

des Zorns"

(but after thy

hardened and

impenitent heart

treasurest up unto

thyself wrath

against the day of

wrath) and conveys

the idea of

"impenitence" in a

rhythmically

palpable manner (the

underlined syllables

are of double

length). The

composer further

reinforces this

effect by repeating

the section a full

tone higher! Bach

has here �therefore

selected a rhythmic

cell in a prose

fragment and

"exploited" it

(rather like a

repeating metrical

foot in poetry)

by treating it

"metrically" - and

this solely to make

the section still

more suggestive.

The second part of

the cantata opens

with a tenor aria

with basso continuo

and obbligato

violino piccolo:

"Erschrecke doch, du

allzu sichre Seele"

(take fright yet,

thou all too

trusting soul) - a

renewed reminder to

bear God's wrath in

mind if we go on

sinning. The

instrumental upper

part called for a

traverse flute at

the first

performance and was

later rewritten for

the violino piccolo

(a somewhat smaller

violin, tuned in

this case a minor

third higher than

the standard

violin), which is

the version we have

decided to perform.

It is striking that

the instrumental

upper voice uses

material which is

completely

independent of the

two other voices

(tenor and basso

continuo) - God's

supreme voice over

the mortal world?

The key is G minor,

the key of inner

agitation.

The ensuing

recitativo

accompagnato (6)

calls for reflection

and penitence: "Beim

Warten ist Gefahr /

Willst du die Zeit

verlieren?..."

(danger lurks in

waiting / wilt thou

lose time?...). The

solo alto (with two

oboes and basso

continuo) declaims

this last piece of

advice in a

dignified, striding

tempo. During the

13-bar fragment, the

oboes keep on

repeating the same

rhythmic figure of

three notes, each of

them separated by an

identical rest; the

main idea of

"waiting" could not

be expressed more

clearly in music.

The cantata ends

with a simple

chorale setting. The

two stanzas of 1630

are uplifting in

nature. The

congregation is to

contemplate life and

death and pray to

God for help and

wisdom.

Sigiswald

Kuijken

Translation:

J & M

Berridge

|

|