|

1 LP -

1C 065-45 646 - (p) 1979

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26521 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63141 2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| CANZONI

DA SONARE |

|

|

|

|

|

| Canzon 1. toni à

10 (1597) - (Giovanni

Gabrieli, um 1555-1612) - Tutti,

Cembalo |

2' 44" |

|

| Canzon La

Cromatica à 4 (1601) -

(Giuseppe Guami, zwischen 1530 u.

1540-1611) - Viole da gamba |

3' 46" |

|

| Canzon

I La Spiritata à 4 (1608) - (Giovanni Gabrieli,

um 1555-1612) - 2 Zinken, 2

Posaunen, Orgel |

2' 54" |

|

| Canzon

sopra "Qui la dira" - (Andrea Gabrieli, um

1510-1586) - Cembalo |

4' 12" |

|

| Canzon

III à 6 (1615) - (Giovanni Gabrieli,

um 1555-1612) - Viole da gamba,

Laute |

3' 07" |

|

Canzon

XXIV à 8 (1608) - (Giuseppe

Guami, zwischen 1530 u. 1540-1611)

|

2' 54" |

|

| -

1. Choro: Viole da gamba, Laute |

|

|

| -

1. Choro: 2 Zinken, 2 Posaunen,

Cembalo, Violone |

|

|

| Canzon

I à 5 (1615) - (Giovanni Gabrieli,

um 1555-1612) - 2 Zinken, 3

Posaunen |

2' 44" |

|

| Canzon

sopra La Battaglia à 4 (1601)

- (Giuseppe Guami, zwischen 1530 u.

1540-1611) - Viole da gamba,

Gitarre |

3' 56" |

|

| Canzon

12. toni à 10 (1597) - (Giovanni Gabrieli,

um 1555-1612) - Tutti, Cembalo |

2' 41" |

|

|

|

|

| Canzon

II à 4 (1605) - (Giovanni

Gabrieli, um 1555-1612) - Viole

da gamba, Orgel |

2' 36" |

|

| Canzon

La Gualmina à 4 (1601) -

(Giuseppe Guami, zwischen 1530 u.

1540-1611) - 2 Zinken, 2

Posaunen, Orgel |

2' 10" |

|

| Canzon

VII à 7 (1615) - (Giovanni

Gabrieli, um 1555-1612) - 2

Zinken, 3 Viole da gamba, 2

Posaunen, Violone, Cembalo |

3' 08" |

|

| Canzon

La Accorta à 4 (1601) -

(Giuseppe Guami, zwischen 1530 u.

1540-1611) - Zink, 3 Viole da

gamba, Orgel |

2' 50" |

|

| Canzon

XXVII à 5 (1608) - (Giovanni

Gabrieli, um 1555-1612) - 2

Zinken, 4 Viole da gamba, 2

Posaunen, Violone, Cembalo |

2' 40" |

|

| Ricercar

sopra Re fa mi don à 4 -

(Giovanni Gabrieli, um 1555-1612) -

Viole da gamba |

5' 07" |

|

| Canzon

XXV à 8 (1608) - (Giuseppe

Guami, zwischen 1530 u. 1540-1611) |

2' 23" |

|

| -

1. Choro: 2 Zinken, 2 Posaunen,

Cembalo |

|

|

| -

2. Choro: Viole da gamba, Laute,

Violone |

|

|

| Canzon

12. toni à 10 (1597) -

(Giovanni Gabrieli, um 1555-1612) -

Tutti, Cembalo |

5' 20" |

|

|

|

|

HESPÈRION XX

|

Instrumente: |

|

| -

Jordi Savall, Diskantgambe |

-

Italienische Diskantgambe unsigniert

(um 1550)

|

|

| -

Christophe Coin, Diskant- und

Altgambe |

-

Diskantgambe unsigniert (um 1700) |

|

| -

Masako Hirao, Tenorgambe |

-

Altgambe von Henry Jaye, Southwark

1629 (1)

|

|

| -

Sergi Casademunt, Baßgambe |

-

Tenorgambe nach John Rose (1598) von

Paul J. Reichlin |

|

| -

Roberto Gini, Baßgambe |

-

Italienische Tenorgambe unsigniert

(1650) |

|

| -

Pere Ros, Violone und Baßgambe |

-

Baßgambe von Pellegrino Zanetto,

Venedig 1550 |

|

| -

Bruce Dickey, Zink |

-

Baßgambe von Barak Norman, London

1697 |

|

| -

Jean-Pierre Canihac, Zink |

-

Violone nach Giovanni Paolo Maggini

(um 1610) von Hans Peter Rast |

|

| -

Jean-Pierre Mathieu, Alt- und

Tenorposaune |

-

Zinken von Philippe Matharel (um

1620) und Christopher Monk |

|

| -

Charles Toet, Tenorposaune |

-

Alt und Tenorposaune von Adolf Egger |

|

| -

Richard Lister, Baßposaune |

-

Tenorposaune M. A. Schnitzer (1581)

(2) |

|

| -

Ton Koopman, Clavicembalo und

Orgel |

-

Tenor- und Baßposaune nach Sebastian

Heinlein (Nürnberg 1621) von Meinl

und Laube

|

|

| -

Hopkinson Smith, Laute und

Gitarre |

-

Cembalo nach einem Instrument um

1580, von Othmar Zumbach |

|

|

-

Orgelpositiv von Bernhard Fleig |

|

|

-

7 chörige Laute von Joel van Lennep |

|

|

-

5 chörige Gitarre von Joel van

Lennep |

|

|

|

|

|

(1)

Aus dem Sammlung historische

Musik-Instrumente im Germanischen

National-Museum Nürnberg |

|

|

(2)

Musée Instrumental du Conservatoire,

Nice |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kirche,

Séon (Svizzera) - 9-13 ottobre

1978 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 065-45

646 - (1 lp) - durata 56' 06" -

(p) 1979 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63141 2 - (1

cd) - durata 56' 06" - (c) 1989 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26521 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 56' 04" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

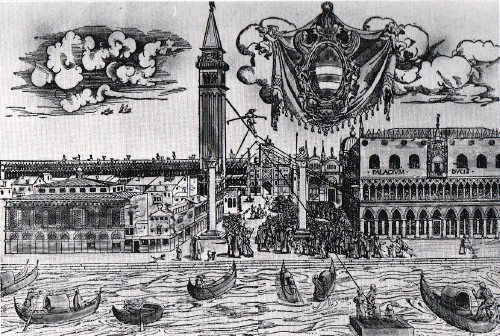

THE

INSTRUMENTAL CANZONA THE

INSTRUMENTAL CANZONA

ln the sixteenth century the

main church of Venice, the

basilica of St Mark’s,

had two organists. Among the

famous musicians who held

these posts were Giovanni

Gabrieli (c. 1553/56-1612)

and Gioseffo Guami (c.

1540-1611). While the

Venetian Gabrieli studied

with his uncle, Andrea,

Guami was a pupil of Adrian

Willaert in Venice. As young

musicians, both spent a few

years (up to 1579) at the

Munich court chapel under

Orlando di Lasso. Gabrieli

was organist of St Mark’s

for over 20 years from 1584;

in 1588-91 he served

alongside Guami, who then

went back to his home town

of Lucca. Nevertheless,

Guami’s Partidura per

sonare delle canzonette

was published in Venice in

1601. Of course, both

organists wrote not only for

the organ: their successive

publications contain

examples of all the

important genres of the

time, mainly motets and

madrigals but also an

increasing number of works

for instrumental ensembles,

in particular in the most

modern form, the canzona. In

the anthology of 36 canzonas

“for every kind of

instrument” published by

Alessandro Raveri in 1608 in

Venice, Gabrieli and Guami

are equally represented.

However, Gabrieli is

undoubtedly the superior

composer, and the standards

he set were promulgated

throughout Italy by his

German pupils Aichinger,

Hassler, and Schütz.

As the character and forms

of instrumental music

changed and were developed

(particularly by Gabrieli),

the way was paved for the

structural and tonal

transformations that led

from the Renaissance to the

early Baroque. The

Renaissance ideal of

independent partwriting

according to the rules of

polyphony still obtained

even in instrumental forms

in the mid-sixteenth

century. If

vocal and instrumental parts

still seemed to be

interchangeable in

performance, they

nonetheless now had their

own distinct character. The

sixteenth century saw the

emancipation of instrumental

music: title-page

indications that pieces

could be sung or played

disappeared as purely

instrumental forms

developed. There is still no

individual idiom for most

instruments, and indications

of instrumentation are

relatively rare: in general

the name of a part gives its

register, and the choice of

instrumentation is left to

the interpreter. This

freedom offered numerous

possibilities in view of the

rich variety of instruments

available. While at the end

of the Middle Ages

instruments of different

kinds (blown, bowed,

plucked) readily played

together, the sixteenth

century favoured the blended

sound of consorts of

matching instruments. Thus

SATB families of the basic

instrumental types

developed. Among them were

the recorder and the

increasingly important viol.

Alto, tenor and bass

instruments (Pommer)

completed the shawn family,

while the nimble cornett

became the top member of the

trombone family.

The development of

independent instrumental

ensemble music took place

above all in Italy, and

primarily through the Venetians

Willaert and Buus. The lack

of a text or a given cantus

firmus

is compensated for by the

structural use of

counterpoint. The present

ricercare by Giovanni

Gabrieli (from a source

manuscript) has as its theme

an abstract sequence of

notes, re-fa-mi-do

(D-F-E-C),

whose elaborate treatment

through several fugal

sections includes inversion

and diminution. From the

1570s in Italy the

“academic” ricercare was

largely superseded by the

canzona. This new

instrumental form derived

from the French chanson and

was at first called the canzona

alla francese per sonare.

The characteristic even and

pointed declamatory

rhythms of the chanson had

quickly been seen as being

especially suited to

instrumental performance.

The typical opening dactyl

rhythm continues to be found

in Gabrieli's

late canzonas.

Janequin’s Chanson La

Bataille (1530) is

especially famous for its

programmatic depiction of a

battle. Numerous battle

compositions, including

those by Guami, take over

features from it, among them

regular rhythmic patterns,

triadic “trumpet-call”

motifs and agitated,

interweaving part-writing.

The pleasing style of the

lively chanson made it

popular throughout Europe in

numerous instrumental

arrangements, particularly

for lute and for keyboard.

Andrea Gabrieli's canzona on

Qui la dira (from his

Canzoni alla francese per

sonar sopra istromenti da

tasti of 1605) is one

of numerous instrumental

versions of this chanson.

Gabrieli does not merely

adapt the chanson for his

instrument, but rather

paraphrases it by taking its

motifs as the basis for

longer imitative sections

and decorating the material

with ornamentation idiomatic

to the keyboard. Such

procedures gave the

instrumental canzona its own

characteristics.

From such arrangements

finally sprang the free

ensemble canzona, which was

newly composed rather than

being based on a

pre-existing composition.

Popular with composers in

northern Italy around 1600,

among them Banchieri,

Canale, G. D. Rognoni and

Massaino, it allowed fullest

scope for their

inventiveness, since the

absence of schematic forms

or rules free rein to

invention and innovation.

This diversity is a

particular feature of

Giovanni Gabrieli`s

canzonas. In clearly

articulated sections,

passages of ricercare-style

imitative writing and

chordal, homophonic passages

follow each other, the metre

varies between common time

and dancing triple-time,

sections are repeated. This

richness of alternation,

rhythm, tempo and phrasing

reflected the new Baroque

striving for contrast. The

open form offered full scope

for individuality too, as

may be seen from the

character titles in Guami's

1601 collection: La

Cromatica, for

instance, uses devices from

the contemporary dramatic

madrigal. The canzona

offered many possibilities

for new instrumental

effects, and the individual

parts soon became

idiomatically instrumental,

with leaps and figures quite

untypical of vocal writing.

Likewise such concertante

features as virtuoso

passages for single solo

instruments and the use of

contrasting instrumental

colours appeared, and the

number of parts increased.

In 1597 Gabrieli took the

number of parts in one

self-contained instrumental

“choir” to ten. This

expansion of texture made

multiple imitation of a

motif possible, while at the

same time the alternating of

different combinations of

instruments resulted in

varying gradations of sound

and also in an almost

block-like density. This led

increasingly to a texture in

which the melodic top part

and harmonically related

bass played the leading

role. Most

editions therefore add an

accompanying figured

bass.The slow speed of

harmonic rhythm also

contributes to the

expansiveness of sound.

Although Gabrieli still

specified the ecclesiastical

modes, his harmony

approaches the major-minor

concept of modern tonality.

Gabrieli’s 36 canzonas,

published between 1597 and

1615, are already more

diverse in polyphonic

technique than Guami’s 26

works. Just in the standard

forces of one or two

fourpart choirs, to which

Guami limits himself,

Gabrieli offers far more

variety. The ten parts of

the canzonas heard here form

one instrumental group, but

in another canzona Gabrieli

separates the instruments

into two groups which (he

still calls “choirs").

The double choirs were

partly suggested bythe two

organs of St. Mark's,

but more particularly by the

north Italian chori

spezzati tradition of

psalm-singing. The

increasing role of

instruments and the

establishing of purely

instrumental forms resulted

in splendid canzonas for

several choirs. Part 1 of

Guami’s Canzona XXIV shows

the basic principle

particularly clearly. A

closed thematic phrase is

stated by one choir and

repeated identically by the

other. This simple

alternation is developed

into a dynamic form by the

interweaving of phrases,

overlapping of instrumental

groups and more powerful

recapitulation in the tutti.

The other extreme is seen in

the eight-part Canzona XXVII

(1608) by Gabrieli,which is

unique in its complexity.

The motivic imitation in the

upper parts and the

dovetailing of the choirs is

so close and dense that only

at one point is the

double-choir layout clearly

audible. Furthermore, an

ostinato-like cadence

formula in the bass is heard

32 times through this

unusual piece. There are two

important factors in this

early Baroque concept of

music: tonal colour and

spatial effect. While

special tone colour is

achieved in Gabrieli’s

ten-part canzonas by the

effect of strings and wind

playing together, tonal

colours are contrasted in

the double-choir canzonas of

Guami. The internal musical

spatial effects in

Gabrieli’s use of the upper

and lower registers in his

ten-part

pieces takes on a spatial

aspect with the double

choir. The placing of

individual instrumental

ensembles in separate places

creates a new effect for the

listener, who is enveloped

in sound that fluctuates in

effect and structure. With

their balconies, galleries

and podia, Baroque churches

- in particular St Mark’s

- provided the architectural

stimuli and conditions for

the realisation of this

spatial art: canzonas,

though instrumental, were

not exclusively secular.

Contemporary accounts tell

us that canzonas were

favourite pieces for festive

public occasions, and they

originated as Staatsmusik

in many cases, though they

were also played to

entertain in the palaces of

the nobility and of

patricians. State

receptions, remembrance days

and, celebrations of victory

were also invariably

accompanied by

ecclesiastical celebrations

rich in pageantry. The

inclusion of canzonas

together with festive motets

in Giovanni Gabrieli’s Sacrae

symphoniae of 1597

demonstrates their

integration into

ecclesiastical music. It

was the task of the church

to articulate the

significance of the city

state in brilliant

ceremonies. As the main

church of the state, St Mark's

was the place of public

ceremonial. Gabrieli was

thus (in 1615) “Organist of

St Mark`s

for the Republic of Venice”.

Since 1567 St Mark’s

had engaged its own

instrumentalists, who were

joined on special occasions

by extra players to form

larger ensembles. Venice

stood not only at the height

of its economic power, but

was also the centre of

artistic activity for

northern Italy and beyond.

The artistic diversity of

the canzona reflects a part

of this great city’s

culture.

Klaus

Wolfgang Niemöller

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|