|

2 LP -

1C 165-45 643/45 - (p) 1979

|

|

| 2 CD - 8

26539 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 2 CD -

CMS 7 63438 2 - (c) 1991 |

|

Alessandrio

Stradella (1644-1682) - La Susanna

(Oratorium)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing

1

|

|

|

| -

Sinfonia avanti l'oratorio |

6' 03" |

|

| PRIMA PARTE |

|

|

| - Recitativo

- (Testo) |

1' 26" |

|

| - Nr. 1 Choro à

tre |

1' 55" |

|

| -

Recitativo - (Testo) |

0' 40" |

|

| -

Nr. 2 Aria |

2' 00" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

0' 59" |

|

| -

Nr. 3 Aria - (Giudice I) |

2' 36" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Giudici I e II)

|

1' 49" |

|

| -

Nr. 4 Aria - (Giudice II) |

2' 32" |

|

| -

Recitativo - (Giudice I) |

0' 31" |

|

-

Nr. 5 Duetto - (Giudici I e

II)

|

1' 56" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Giudici I)

|

0' 27" |

|

| -

Nr. 6 Aria - (Giudice I) |

1' 34" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Giudici I e II)

|

0' 18" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

1' 34" |

|

| -

Nr. 7 Choro à tre |

1' 42" |

|

|

|

|

- Recitativo

- (Testo)

|

1' 34" |

|

| -

Nr. 8 Aria - (Susanna) |

2' 16" |

|

| - Nr. 9 Aria

- (Susanna) |

3' 29" |

|

- Recitativo

- (Susanna)

|

1' 31" |

|

- Nr. 10 Aria

- (Susanna)

|

1' 48" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

1' 57" |

|

- Nr. 11 Aria

- (Testo)

|

1' 54" |

|

- Recitativo

- (Testo)

|

0' 44" |

|

- Nr. 12 Duetto

- (Giudici I e II)

|

0' 59" |

|

- Recitativo

- (Susanna)

|

0' 38" |

|

- Nr. 13 Duetto

(Arioso) - (Giudici I e II)

|

0' 58" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Susanna.

Giudici I e II)

|

1' 27" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

1' 12" |

|

| - Nr. 14 Choro

à cinque |

2' 36" |

|

| Long Playing

2 |

|

|

| SECONDA PARTE |

|

|

-

Nr. 15 Aria - (Testo)

|

2' 51" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

1' 16" |

|

-

Nr. 16 Aria - (Susanna)

|

6' 37" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Susanna)

|

0' 56" |

|

-

Nr. 17 Aria - (Susanna)

|

3' 25" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

1' 08" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Giudice I)

|

0' 34" |

|

-

Nr. 18 Duetto - (Giudici I e

II)

|

1' 31" |

|

- Recitativo

- (Testo)

|

1' 48" |

|

-

Nr. 19 Aria - (Susanna)

|

3' 40" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Susanna)

|

1' 15" |

|

|

|

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

0' 46" |

|

- Recitativo

- (Daniele)

|

0' 29" |

|

-

Nr. 20 Aria - (Daniele)

|

1' 31" |

|

| - Recitativo

- (Daniele) |

0' 46" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

0' 28" |

|

-

Nr. 21 Aria - (Daniele)

|

1' 50" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Daniele e

Giudice I)

|

0' 20" |

|

-

Nr. 22 Aria - (Daniele)

|

2' 32" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Daniele e

Giudice II)

|

0' 58" |

|

-

Recitativo - (Testo)

|

2' 01" |

|

-

Nr. 23 A tre - (Susanna e due

Giudici)

|

3' 06" |

|

| - Recitativo

- (Giudice I) |

0' 48" |

|

| - Recitativo

- (Testo) |

1' 02" |

|

| - Nr. 24

Choro à tre |

1' 53" |

|

| - Nr. 25

Choro à cinque |

1' 10" |

|

|

|

|

| Marjanne

Kweksilber, Susanna (Sopran) |

Instrumentarium: |

|

| Judith Nelson,

Daniel (Soprano) |

Barockviolinen: nach

Maggini, München, um 1800; Joseph Klotz,

Deutschland 1789 |

|

| René Jacobs,

Testo (Altus) |

Barockvioloncello:

Deutschland 18. Jahrhundert |

|

| Martyn Hill,

Giudice II (Tenor) |

Violone: E.M.

Pöhlmann, 1975 |

|

| Ulrik Cold,

Giudice I (Baß) |

Cembalo:

Italienischer Art: Wilhelm Kroesbergen |

|

|

Theorbe:

Erzlaute (Kopie) von Jacob van de Geest,

1974 |

|

Ingrid Seifert,

Hajo Bäss, Barockvioline

|

Chitarrone:

Kopie nach Tieffenbrucker von Jacob van de

Geest, 1973 |

|

| Jaap van ter

Linden, Barockvioloncello |

|

|

| Jeroen van der

Linden, Violone |

|

|

Alan Curtis,

Cembalo und Leitung

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alan Curtis,

Leitung |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde

Gemeente Kerk, Amsterdam (Olanda)

- settembre 1978 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 165-45

643/44 - (2 lp) - durata 51' 50" /

44' 42" - (p) 1979 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CMS 7 63438 2 - (2

cd) - durata 51' 52" / 44' 39" -

(c) 1991 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26539 2 - (2 cd) -

durata 51' 52" / 44' 38" - (c)

2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Alessandro

Stradella is one of those

composers whose name never

fell into oblivion after his

death, in contrast to most

of his contemporaries. It is

true that this cannot be

credited to his musical

output, but to the

adventurous events of his

life, which have constantly

attracted the phantasy of

romantic writers. Many times

has Stradella been produced

on the opera stage as a

hero, and the writers of

various papers on musical

history did not fail at

least to referto his violent

end as the result of a love

affair. All that, however,

had but little effect on the

knowledge and fostering of

the extensive works which

the thirty-eight year old

composer left for posterity.

It is

only recently that his art

has begun to be evaluated

again and attract attention,

just the same as his life,

about which little was known

apart from the sensational

incidents. It is

above all through the

copious biography of

Stradella by Remo Giazotto

that today we know of his

origins, the musical scene

of his youth and what befell

him later: other scholars,

especially the American Owen

Jander, made valuable

contributions to the further

knowledge of him, and above

all of the works he

composed. Alessandro

Stradella is one of those

composers whose name never

fell into oblivion after his

death, in contrast to most

of his contemporaries. It is

true that this cannot be

credited to his musical

output, but to the

adventurous events of his

life, which have constantly

attracted the phantasy of

romantic writers. Many times

has Stradella been produced

on the opera stage as a

hero, and the writers of

various papers on musical

history did not fail at

least to referto his violent

end as the result of a love

affair. All that, however,

had but little effect on the

knowledge and fostering of

the extensive works which

the thirty-eight year old

composer left for posterity.

It is

only recently that his art

has begun to be evaluated

again and attract attention,

just the same as his life,

about which little was known

apart from the sensational

incidents. It is

above all through the

copious biography of

Stradella by Remo Giazotto

that today we know of his

origins, the musical scene

of his youth and what befell

him later: other scholars,

especially the American Owen

Jander, made valuable

contributions to the further

knowledge of him, and above

all of the works he

composed.

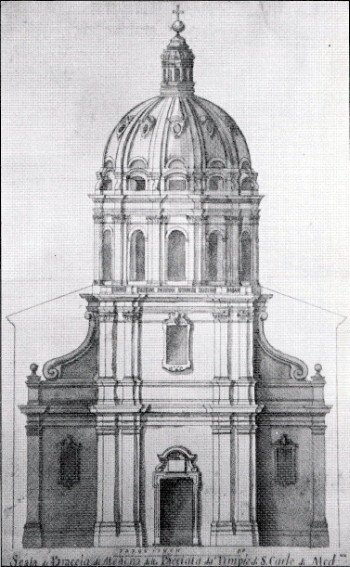

Alessandro Stradella was

born in Rome

an October lst 1644 and

baptised three days later in

the church of S. Celso e

Giuliano, near the Piazza Navona,

and he spent his childhood

in that vicinity. His

parents, Marcantonio

and Simona Stradella, had

only arrived in Rome

shortly before, both came

from the Modena district and

had clearly

left their home only

reluctantly. Cavaliere Marcantonio

Stradella had been Governor

of the Modena fortress Vignola

in the years 1642/43

and had fled in order to

extricate himself from his

duties there owing to the

violent struggles between

the Pope and the Duke of

Modena, and it would appear

that was in no way due to

cowardice nor for his own

advantage, but on the advice

of Sig. Ugo Boncampagni of Vignola,

who was in an awkward

position as Roman

lord and feudal lord of

Modena, and clearly wanted

to avoid a direct

confrontation. The

Stradellas first went to

another estate of

Boncampagni’s Montefestino,

and there spent a difficult

time in exile, with Simona

already pregnant with the

future composer. With a

recommendation from

Boncampagni to the powerful

Pamfili

family, of which,

Giambattista had just

ascended the Papal throne as

Pope Innocence X. they went

to Rome. The father was in

fact entrusted with several

commissions by the Pamfilis,

without however being able

to gain a firm appointment

or regular salary. An

attempt to extricate himself

from this situation by

seeking an act of grace from

the Duke of Modena was

unsuccessful, and in 1655

Marcantonia Stradella died

in Rome. His youngest son

Alessandro grew in the world

of lay piety evolved by the

spirit of the holy Filippo

Neri, as was fostered at S.

Giovanni dei Fiorentini, at

Vallicella

and other spiritual centres,

and in which the musical

oratorio also had its roots.

It

would appear that even as a

child Stradella took part in

musical performances in

these circles and part of

his training was due to

them, and he then completed

his musical education with

the wellknown Roman

master, Ercole Bernabei.

The father tried in vain to

get him accepted into the

seminary of the Augustines

in Acquapendente,

where Alessandro's

elder brother Francesco was

already about to take his

priest’s vows. In

1657, two years after his

father, his mother died, who

had also had no success in

her desire to return to

Modena or to obtain a grant

from the duke. As

Alessandro's middle brother

had also left home and his

sister had married, the

young musician had to look

around for lodgings, which

he doubtless with the help

of the powerful and rich

families of the Roman

nobility (such as the

Pamfili). Some years later

we find him, already a

respected musician, in

ecclesiastical music circles

as the already-mentioned

cultural centres of

Phillipine spiritual

learning and of the musical

oratorio, in his connection

as favourite of the Pamfili,

Aldobrandini, Colonna and

not least of Queen Christina

of Sweden, who after

abdicating the throne and

being converted to the

Catholic faith had chiefly

lived in Rome,

at first received in triumph

by the pope and people, but

who was later found to be a

liability in many respects.

In

any case, Christina gathered

around her a veritable court

of the muses of all the

arts, among which music

played a leading part. The

young Stradella was

recommended to her as

singer, lutenist and violin

player. Stradella composed

for the queen an Latin Motet

in honour of Filippo Neri

Chare Jesu soavissime

which was performed on the

saint’s birthday on July

21st, 1663. The text was

also by Stradella, who was

an accomplished poet in Italian

and Latin. He scored a big

success, Christina bestowed

gifts on the

eighteen-year-old, and

appointed him as her

“servitore da camera", which

in fact was neither a

position nor a providerof

any income. In

1665 the Contestabile

Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna and

his wife Maria Mancini,

although they were not

really close friends of

Christina, asked her for the

young musician and this

request was granted upon the

advice of the gueen's

confidants, Cardinal Decio

Azzolino and Giacomo

d’Alibert. Stradella got to

know important people in

Colonna’s circle, such as

the future Vienna Court poet

Nicolò

Minato, the Roman Lelio

Orsini (a

member of the well-known

family of the nobility), who

was also active as a poet,

and Giovanni Paolo Monesio,

whose diaries today provide

a valuable insight on

Stradella’s life. True it

must be said that this very

Monesio, who had to flee

from Rome

for a time

for fraud against the

above-mentioned Orsini and

later held court in Genoa

with Stradella’s later

benefactor Marchese Rodolfo

Maria Brignole Sale, one of

those personalities

surrounding Stradella who

did not always tray to

achieve their aims by

ethical means. To them must

be added also the musician

Carlo Ambrogio Lonati, who

just like Monesio always

seems to turn up at

Stradella’s side in

important phases of his

life. At the same time the

composer had the first of

his love-affairs with the

singer Pia Antinori, who was

also in the service of

Colonna. In December 1663,

the Colonnas went to Venice,

and with them Stradella,

Antinori and Minato. However

Stradella returned to Rome

in April via Florence. But

he did not stay here very

long either and then went

with Christina of Sweden’s

young protegee Giorgina Cesi

to Florence. The couple

separated here and Stradella

made a passionate

acquaintance with a young

nun called Lisabetta

Marmorari, whom he had only

seen on one single occasion

during a religious ceremony.

He remained true to this

passion for years, and when

Lisabetta left the nunnery,

hoped to be able to marry

her and in 1673 with Lonati

made an attempt to abduct

her, which was forcibly

prevented. He then stayed in

Florence, with a stop in Rome

from February to April 1667,

and returned to Rome

at the beginning of 1668

with Colonna, who himself

was returning from Venice to

Rome. Here his fate began to

take a downward turn. He

left the service of the

princely family, to allow

himself to get involved in

fraudulent affairs with the

poet-monk Antonio Sforzy and

the ever-present Lonati who

were also accompanying

Colonna to Rome.

He sought to avoid the

danger of detection by

fleeing in 1670 he went with

Monesio to Vienna, where he

also met Lonati again. It

would not seem that

Stradella achieved any

tangible successes at the

imperial court. As it was

only Sforzy who was brought

to justice and sentenced to

several years in prison in

connection with the

above-mentioned affair,

Stradella was able to return

to Rome in October 1670. He

secured employmen tat the

recently-opened Teatro

Tordinona for whose

foundation he had worked for

years with d’Alibert and the

librettist Flilippo

Accajuoli. However, he did

not succeed in obtaining the

position he had hoped for as

leading composer of this

theatre: this in fact was

given to Bernardo Pasquini,

while Stradella had to

content him self with the

composition of Prologues and

entractes. However, he wrote

opera for other occasions,

among them those

commissioned by Colonna and

Christina. In

1675 he composed for S.

Giovanni dei Fiorentini one

of his most famous works,

the oratorio S. Giovanni

Battista.

Stradella's patrons, who

were those who obtained

performance of an oratorio

there: Santa Edita,

vergine e monaca,

regina d'Inghilterra,

probably written in 1665 and

commissioned by Colonna. The

text was probably by Lelio

Orsini an is of interest in

respect of Stradella’s

life-style then, in that

there is an open connection

with Christina of Sweden.

True it is not, as might at

first be thought from the

work’s contents, a homage to

the queen -

it is concerned with a queen

who renounces all the

world's power and honour

(“spernere mundum" is part

of Filippo Neri’s

motto) and gives up her

crown in favour of an

ascetic life in a convent.

Remo Giazotto thinks, on the

contrary, that here

Christina, who did in fact

give up her crown but did

not afterwards go on to lead

ascetic life, was really to

be presented as a

contradictory example and

the real main character was

a poetic glorification of

queen Catherine of Braganza,

wife of Charles the Second

of England.

In

contrast to this work,

however Susanna was

really written in direct

consultation with Christina

and must have been composed

at her behest. It is true

that a performance of the

work can first be traced to

1681 in the Oratorium S.

Carlo in Modena by reason of

the surviving text-book, and

the only score of the work

surviving there bears this

date (which however can only

refer this actual

performance). On the other

hand there is evidence which

cannot be overlooked, that

an oratorio written by

Stradella, commissioned by

Christina in 1666, was in

fact Susanna. In

fact when Stradella’s nephew

in 1662 left the Duke of Modena

various musical scores of

his murdered uncle, among

them was also La Susanna

per la regina di Svezia, l'anno

1666. This was the

year when Stradella had

arrived in Rome shortly before

Christina's

departure for Hamburg, and

had received the commission

from her at short notice;

the work must have been

composed between May 7th and

16th.

This work must have

represented a long-nurtured

wish by Christina and in its

performances she must have

seen a realisation of the

phantasies which she had

felt for many years. The

performance took place on

the evening before the

departure of the queen. It is

reported that she insisted

that the title role be sung

by a woman, which was then

quite exceptional (the high

voices were

normally sung by castrati).

The singer was Giorgina

Cesi, with whom Stradella

soon departed to Florence.

He is said to have protested

against her participation,

but his doubts then turned

to enthusiasmen, although

this was in no way only due

to Giorgina’s musical gifts.

Out of regard for her

Stradella is said to have

replaced an aria already

composed by a new one, which

due regard is paid to

Susanna's beauty.

Furthermore, Stradella was

not the only admirer of

Giorgina; d'Alibert also had

ambitions to play the role

of her

protector but was thwarted

by Monesio,

who managed to acquaint

d’Alibert’s wife of what was

going on, although he

himself was similarly

stricken.

Many

of the characteristics from

which the importance of the

composer today is constantly

more and more recognised and

explored crop up in the

music of Susanna. It is

above all his uncanny touch

in portaying situations and

characters, in which he made

use of the means at his

disposal in melody, rhythm,

instrumentation etc. with

utter freedom of variety and

arrangement according to the

needs of the moment. Thus he

frequently changes from

“dry” recitative (often the

opera prologue, with its

extensive pauses, resembles

musical declamation) to more

lively arioso passages: the

being always governed by the

requirements of the basic

text at that moment, and of

the inner and outer dramatic

situation.

Behind this lies Stradella's

special affinity to the

word, he being himself a

poet, and also his

passionate involvement which

just as in his life also

constantly characterised his

art. Just as in the great

work S. Giovanni Battista

the art of characterisation

comes out in the contrasting

of the various personalities

- John at the same time

painful and triumphant, the

seductive Herodias and her

daughter, the tragic and

tortured weakling Herod - in

Susanna there exists

a similar situation; the two

voluptuous old people in

their ceaseless drive with

us of all available means,

Susanna both heroic and

sensitive, unshakable in her

trust in God, and finally the

vicotrious prophet

Daniel, who brings about a

solution to the conflict.

The counterplay of

these characters which

changes according to the

point reached in the plot

also makes its musical mark

on

the situations which follow

each other; for instance

in the trios of Susanna and

the

two judges at the beginning

and end of the work,

although Susanna is at

first confronted in her

resolution by the pressures

of the old people, at the

end she scores a complete

triumph, musically as well,

in sovereign style over the

two, now wholly defeated.

Naturally, just as

did the entire music of the

Baroque, Stradella makes use

of specific turns of phrase

and devices of composition,

which he employs in fine style

for the needs of the moment.

As an example might be

mentioned the various styles

of the Ostinato technique

(not, it is true, in the

"literal" conception

of the constant return of

the same theme), where the

relentless progress, as is

were, of the musical motion

reflects a preoccupation

with the situation of the

moment, and often its

musical, inevitability. In

whatever way he employs

these means, Stradella

always shows himself from

the technical point of view

to have a complete knowledge

and command of the technique

of movement-construction as

is apparent, for example, in

the contrapuntal nature of

the instrumental part,

always effected with

artistry, but also in the

chorus and ensembles. This

universal ability, coupled

with passionate inspiration

enables us to understand why

a contemporary of his, on

the news of his tragic

death, exclaimed “An Orpheus

assassinated".

Geoffrey

Child

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|