|

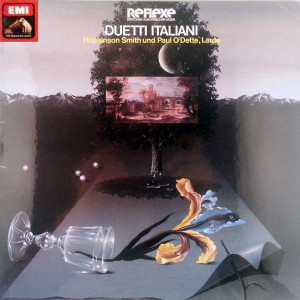

1 LP -

1C 065-45 642 - (p) 1979

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26517 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| DUETTI

ITALIANI - Italienische Lautenduette des

16. unf frühen 17. Jahrhunderts |

|

|

|

|

|

| - Chi passa

(Anonym, Herausgeber: Pierre

Phalese, 1571) - Lauten b) und

f) |

1' 39"

|

|

| - Canti di voi

le ladi (Ubert Naich,

Herausgeber: Pierre Phalese, 1571) -

Lauten b) und f) |

1' 26" |

|

| - Amor e

gratioso (Anonym, Herausgeber:

Pierre Phalese, 1571) - Lauten

b) und f) |

1' 54" |

|

- Passomezo -

Saltarello (Giovanni Pacoloni,

Herausgeber: Pierre Phalese, 1571) -

Lauten b) und f)

|

1' 58" |

|

| -

Canon (Francesco da Milano,

1497?-1573) - Lauten d) und e) |

1' 17" |

|

| -

Fantasia sexta (Francesco da

Milano, 1497?-1573 und Johannes

Matelart, Herausgeber 1559) - Lauten

d) und e) |

1' 36"

|

|

| - Fantasia terza

(Francesco da Milano, 1497?-1573 und

Johannes Matelart, Herausgeber 1559)

- Lauten c) und f) |

1' 53" |

|

| -

Spagna (Francesco da Milano,

1497?-1573) - Lauten b) und c) |

1' 33" |

|

| -

Gloria della "Missa Dixit Joseph"

(Orlando di Lasso, 1532-1594) - Lauten

a) und d) |

5' 13" |

|

| -

Calata (Joananbrosio Dalza,

Herausgeber 1508) - Lauten b)

und f) |

2' 03" |

|

| -

Saltarello Piva (Joananbrosio

Dalza, Herausgeber 1508) - Lauten

b) und f) |

4' 20" |

|

|

|

|

| - Contrapunto

primo di B.M. (Bernardo

Monzino, Herausgeber: Vincenzo

Galilei 1584) - Lauten d) und e) |

1' 58" |

|

| - Duo tutti di

fantasia (Vincenzo Galilei,

1520-1591, Herausgeber: Vincenzo

Galilei 1584) - Lauten d) und e) |

1' 11" |

|

| -

Contrapunto secondo di B.M.

(Bernardo Monzino, Herausgeber:

Vincenzo Galilei 1584) - Lauten

d) und e) |

2' 11" |

|

| -

Pavana Milanese - Saltarello

(Pietro Paolo Borrono, Herausgeber

1543) - Lauten b) und f) |

3' 15" |

|

| -

Canzona prima di Claudio da

Correggio (Giovanni Antonio

Terzi, Herausgeber 1593) - Lauten

d) und e) |

3' 38" |

|

| -

Contrapunto sopra Petit Jaquet di

Claudio da Correggio (Giovanni

Antonio Terzi, Herausgeber 1593) - Lauten

d) und e) |

4' 10" |

|

| -

Canzona seconda di Claudio da

Correggio (Giovanni Antonio

Terzi, Herausgeber 1593) - Lauten

d) und e) |

4' 08" |

|

| -

Toccata à dui Liuti

(Alessandro Piccinini, 1566-1638,

Herausgeber 1623) - Lauten d)

und e) |

3' 21" |

|

|

|

|

| Hopkinson Smith,

Laute |

Folgende Lauten

wurden verwendet: |

|

| Paul O'Dette,

Laute |

a) = 7 chörige

Sopranlaute von Mathias Durvie, Paris

1977 |

|

|

b) = 6 chörige

Altlaute von Nico van der Waals,

Oudkarspel (Niederlande) 1976 |

|

|

c) = 6 chörige

Altlaute von Stephan Murphy,

Mollans-sur-Ouvèze 1978 |

|

|

d) = 10 chörige

Tenorlaute von Nico van der Waals, Oudkarspel

(Niederlande) 1975 |

|

|

e) = 7 chörige

Tenorlaute von Joel van Lennep, Boston

(USA) 1974 |

|

|

f) = 6 chörige

Tenorlaute von Joel van Lennep, Boston

(USA) 1976 |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kirche,

Séon (Svizzera) - 5-7 giugno 1978 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 065-45

642 - (1 lp) - durata 50' 04" -

(p) 1979 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26517 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 50' 04" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

DUETTI ITALIANI DUETTI ITALIANI

The art of duetting is

certainly as old as music

itself for what could be more

satisfying than one’s own

instrument but two ofthe same?

The resulting interaction of

two performers and their

exchange of musical ideas

creates an intensity and

vitality that is perhaps

unique in the world of chamber

music. Two equal instruments

allow the possibility of

alternating the musical

functions of melody and

accompaniment, challenging

each performer to match the

other, often in quick

succession.

Considering the popularity of

the lute in the Renaissance,

it is hardly surprising that

the lute duet became so

important and influential. The

size and diversity of this

repertoire, over five hundred

extant pieces representing

nearly every style and form of

Renaissance music, is

remarkable. The duet

literature contains many works

of great musical

sophistication and profundity,

such as Terzi’s Contrapunto

sopra Petit Jaquet and

Piccinini's

Toccata à dui Liuti,

and many with no pretense to

more than entertainment or

instruction. These latter,

including heterophonic dances

and short contrapuntal

exercises, make up in spirit

what they may lack in loftier

characteristics. Renaissance

duets thus provide the

lutenist with a literature of

extraordinary energy and

challenge. Within this

repertoire, Italian duets

stand apart in terms of

variety and virtuosity.

While most European countries

treated the lute duet as

‘Gebrauchsmusik’, in Italy it

was part of the professionals

standard repertoire. Whereas

in England, for example, duets

were frequently used as

individual display pieces, one

performer executing

spectacular variations over

the chordal accompaniment of

the other, in Italy the same

high degree of technical

proficiency was often demanded

of both players, elaborate

flourishes being tossed back

and forth. Not intoxicated by

sheer virtuosity, however, the

Italians made numerous tonal

experiments, combining lutes of

various tunings and sizes to

create special timbres and to

help distinguish polyphonic

lines more clearly. The duets

on the present recording

represent seven distinct

types:

1.

counterpoint against a chanson

or madrigal

2. melody

over a drone

3.

counterpoint over a "cantus

firmus"

4.

intabulation of a pre-existing

vocal or instrumental work

5. melodic variations

over a repeated harmonic

pattern (ground)

6. a solo

fantasia with a new,

superimposed second lute part

7. entirely

original compositions not

based on any pre-existing

material.

Early duetting was an

improvisatory art, as Johannes

Tinctoris explained in his De

Inventions et Usu

Musicae

of 1484: “Thus some teams will

take the treble of any piece

you care to give them and

improvise marvellously upon it

with such taste that the

performance cannot be

rivalled. Among such, Pietro

Bono (Avogari), lutenist to

Ercole, Duke of Ferrara, is in

my opinion pre-eminent.”

Bono, the most renowned

virtuoso of the fifteenth

century, was assisted by a

‘tenorista’, who supplied

either a drone, cantus firmus,

or the lower voices of a

chanson, over which the master

improvised fanciful disivions.

Early sixteenth century duets

in the “counterpoint against a

chanson” style maintain a

clear separation of the roles

of soloist and accompanist,

the treble lute ornamenting

the cantus line or improvising

a new discantus, while the

tenorista provided a

simplified version of the

lower two parts. Later in the

century, the accompaniment was

expanded to include all the

voices of the vocal model. The

resultant fuller texture

delegated more interest to the

accompaniment, leaving the

counterpoint less exposed, and

thus reassigning its earlier

solistic role to one of

commentary, sometimes taking

melodic initiative, sometimes

supplying a textual background

to the now selfsufficient

accompaniment. The master of

this new style was Giovanni

Antonio Terzi, whose books of

1593

and 1599

contain some of the most

sophisticated lute music ever

published. His Contrapunto

sopra Petit Jaquet

covers an incredible three and

one-half octave range,

including breath-taking leaps

and jazzy syncopations. The

Saltatello and Piva of Dalza

represent the last remnants of

the medieval tradition of

improvisation over a drone.

The repetitive nature of a

drone allowed the improviser

to utilize his extensive "bag

of tricks", including hemiolas

and dissonances. The main

responsibilities of the

tenorista were rhythmic drive

and solidity, although he

certainly added a few

cross-rhythms and ornaments of

his own.

La Spagna was the most

popular cantus during the late

fifteenth and early sixteenth

centuries. In

Francesco da Milano’s

setting it is concealed in the

middle of a chordal

accompaniment over which he

composed a graceful, flowing

countermelody. Although not

one of Francesco's more

involved works, it makes a

pleasant contrast to the

complex polyphony for which he

is primarily known.

The skill of a lutenist was

often judged by his ability to

devise imaginative

arrangements of chansons,

madrigals, motets and

canzonas. In

making these intabulations, a

lutenist rarely maintained the

precise notes of the original,

but usually employed a certain

amount of ornamentation

rendering them more idiomatic

for his instrument. The lute

cannot sustain the long notes

commonly Found in vocal music,

as the sound of a plucked

string dies rapidly. These

long notes were replaced with

scale passages through which

the lutenist could crescendo

or decrescendo as a singer

would do on a sustained note.

Three contrasting approaches

to intabulation

are represented on this

recording. The Gloria from Lassus'

Missa

Super Dixit Joseph

is mostly

unembellished, runs having

been added only as was deemed

necessary to facilitate

phrasing. Canti di voi le

ladi and Amor e

gratioso are somewhat

more elaborately embellished,

but the basic structure of the

originals remain. Claudio da

Correggio’s two Canzone on the

other hand, are barely

recognizable through Terzi’s

flamboyant ornamentation. The

new works which result,

however, attest to the

artistry oflan imaginative

intabulater.

Such artistic license was as

controversial then as it is

today. Writers such as Ganassi

and Zacconi contended that

performers who didn't ornament

were not thought well of by

their colleagues, while Josquin

and Zarlino, among others,

argued that ornamentation was

unnecessary and served only to

disrupt the counterpoint.

Contrasting the complexities

of vocal music are the simple

repeated harmonies of the

ground bass dances. The two

most common Renaissance

grounds were the Passamezo

antico and the Passamezo

moderno: Borrono’s Pavana

Milanese and Saltarello

are based on the former, Pcoloni's

Passamezo and Saltarello on

the latter. The chord

progressions of Chi passa

are

derived from

a street song ofthe same name.

Although the Contrapunto

secondo begins like a

Passamezo moderno,

there are no repeated paterns,

and, in fact,

both of the so-called

“grounds” to B.M.'s Contrapunti

are through-composed in a

madrigalesque manner, These

pieces are essentially

ricercars, one lute

functioning in a predominately

harmonic fashion, the other

providing rhythmic and melodic

impetus.

In

1559, the Flemish lutenist Johannes

Matelart

published several of Francesco

da Milano's solo

fantasias, to which he had

composed a second lute part.

These new parts, while partly

obscuring the original

compositions, enrich the

texture with additional points

of imitation, parallel thirds,

and parallel sixths, creating

a lushness of sound immatched

at this early date.

The latest surviving

Renaissance duet, and perhaps

the most spectacular, is the Toccata

à dui Liuti by

Alessandro Piccinini. Not

content with the strict

separation of melody and

accompaniment roles, Piccinini

at times supplies passagework

in both parts simultaneously.

Moving either in parallel or

in contrary motion, this

device builds energy and aids

in gathering momentum.

Although the contrapuntal

style is that of the

Renaissance, the contrasting

sectionalism ushers in the

world of the Baroque. The

grand dimensions of this piece

bring to a close the era of

the Renaissance lute duet and

serve as an appropriate finale

to this recording.

Paul

O'Dette

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|