|

1 LP -

1C 065-30 944 Q - (p) 1978

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26513 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| LAUTENMUSIK

VON SILVIUS LEOPOLD WEISS (1686-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Suite d-moll |

|

|

| - Prélude |

1' 22" |

|

| - Allemande |

3' 22" |

|

| - Courante |

1' 41" |

|

| -

Menuets I und II |

2' 30" |

|

| -

Bourrée |

1'

45"

|

|

| - Sarabande |

2' 19" |

|

| -

Gigue |

1' 48" |

|

| Tombeau

sur la Mort de M. Conte de Logy

arrivée 1721 |

8' 53" |

|

|

|

|

| Prélude und

Fantasie c-moll |

4' 40" |

|

| Suite D-dur |

|

|

| -

Prélude |

1' 50" |

|

| - Aria |

5' 05" |

|

| -

Courante |

3' 17" |

|

| -

Sarabande |

4' 27" |

|

| -

Passagaille |

4' 05" |

|

| -

Gigue |

2' 57" |

|

|

|

|

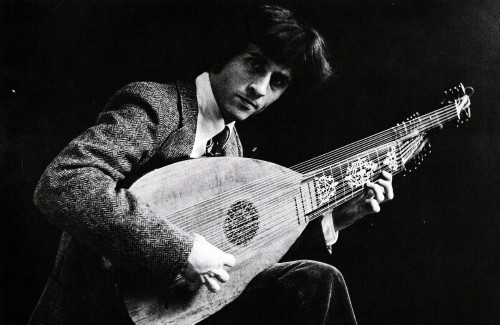

Hopkinson Smith, Theorbe

(Laute) von Leopold Widhalm, Nürnberg

1755

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Séon

(Svizzera) - novembre 1977 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 065-30

944 Q - (1 lp) - durata 50' 01" -

(p) 1978 - Analogico

(Quadraphonic) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26513 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 50' 01" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Silvius

Leopold Veiß (1686-1750) is

without question the most

important lutenist of the

German baroque and one of the

greatest of all time. His

historical significance would

be firmly established by

virtue of his enormous output

alone, for he left over

seventy sonatas

(suites) in tablature, by far

the largest corpus of music

for solo lute of any composer

in the history of the

instrument. However, the

quantity of these sonatas is

matched by their quality. In 1782

Bach’s biographer Forkel

praised the “excellent and

difficult compositions” of

Weiß, “which are written in

the pure and pithy style, much

like the harpsichord works of

the late J. S. Bach.” Born in

Breslau, weiß

learned to play the

lute as a boy from his father

Johann Jakob, as did Silvius’

younger brother Johann

Sigismund. Virtually nothing

is known about the weiß family

until the two young lutenists

were engaged at the Palatinate

court in Düsseldorf

in 1706. Two years later

Silvius accompanied the Polish

Prince Alexander Sobiesky to Italy,

where the two remained until

the Prince’s death in 1714.

This Italian

sojourn had a profound impact

on Weiß's

musical style, since the music

he composed afterwards show a

strong influence of Italian

concerto elements. ln 1717

Weiß appeared at the court of

August the Strong, King of

Poland and Elector of Saxony

in Dresden. A year later he

was permanently attached to

the Dresden Hofcapelle, and

kept the position of court

lutenist there for the rest of

his life. By 1744 he was the

highest-paid instrumentalist

in the Hofcapelle, a measure

of the esteem in which he was

held by his sovereign. Weiß’s

fame was not restricted to the

Dresden court, however. As

early as 1713 the prominent

Hamburg critic and composer

Johann Mattheson

described Weiß

as "a

perfect musician," and in 1728

as “the greatest lutenist in

the world,” though Weiß was

known to him almost

exclusively by reputation. In his

Study of the Lute

(1727), Ernst Gottlieb Baron

raves for two pages about

Weiß's accomplishments: “I can

sincerely testify that it

makes no difference whether

one hears an ingenious

organist performing his

fantasias and fugues on a

harpsichord or hears Monsieur

Weiß playing.” This great

skill and renown drew lute

students to Dresden from all

over Germany and from as far

away as Russia. Through this

personal contact and through

the wide circulation of his

pieces in manuscript, Weiß’s

influence on the younger

generation of lutenists was

considerable. Silvius

Leopold Veiß (1686-1750) is

without question the most

important lutenist of the

German baroque and one of the

greatest of all time. His

historical significance would

be firmly established by

virtue of his enormous output

alone, for he left over

seventy sonatas

(suites) in tablature, by far

the largest corpus of music

for solo lute of any composer

in the history of the

instrument. However, the

quantity of these sonatas is

matched by their quality. In 1782

Bach’s biographer Forkel

praised the “excellent and

difficult compositions” of

Weiß, “which are written in

the pure and pithy style, much

like the harpsichord works of

the late J. S. Bach.” Born in

Breslau, weiß

learned to play the

lute as a boy from his father

Johann Jakob, as did Silvius’

younger brother Johann

Sigismund. Virtually nothing

is known about the weiß family

until the two young lutenists

were engaged at the Palatinate

court in Düsseldorf

in 1706. Two years later

Silvius accompanied the Polish

Prince Alexander Sobiesky to Italy,

where the two remained until

the Prince’s death in 1714.

This Italian

sojourn had a profound impact

on Weiß's

musical style, since the music

he composed afterwards show a

strong influence of Italian

concerto elements. ln 1717

Weiß appeared at the court of

August the Strong, King of

Poland and Elector of Saxony

in Dresden. A year later he

was permanently attached to

the Dresden Hofcapelle, and

kept the position of court

lutenist there for the rest of

his life. By 1744 he was the

highest-paid instrumentalist

in the Hofcapelle, a measure

of the esteem in which he was

held by his sovereign. Weiß’s

fame was not restricted to the

Dresden court, however. As

early as 1713 the prominent

Hamburg critic and composer

Johann Mattheson

described Weiß

as "a

perfect musician," and in 1728

as “the greatest lutenist in

the world,” though Weiß was

known to him almost

exclusively by reputation. In his

Study of the Lute

(1727), Ernst Gottlieb Baron

raves for two pages about

Weiß's accomplishments: “I can

sincerely testify that it

makes no difference whether

one hears an ingenious

organist performing his

fantasias and fugues on a

harpsichord or hears Monsieur

Weiß playing.” This great

skill and renown drew lute

students to Dresden from all

over Germany and from as far

away as Russia. Through this

personal contact and through

the wide circulation of his

pieces in manuscript, Weiß’s

influence on the younger

generation of lutenists was

considerable.

Yet despite this fame, little

information survives todaz about

his appearance, his

familz, or his personal

affairs. The onlz likeness of

him, the engraving reproduced

here, was made in the

eighteenth century after a

contemporary painting by the

great portraitist Balthasar

Denner. The painting, now

lost, was probably executed in

about 1730. In

approximately 1720 Weiß married,

and had seven children by his

death in 1750; at least two of

them were talented musicians.

Though he was well paid, he

apparently lived rather too

well, since his family was

destitute after his death. Of

his personality, one old

anecdote is perhaps

characteristic: “In the

fiftieth year of his life

(1736) the great lutenist Weiß answered

the question of how long he

had been playing the lute with

"twenty

years".

One of his friends, who knew

for certain that Weiß already

was playing the lute in his

tenth year, wanted to

contradict him, but he

interrupted and said, "True,

but for twenty years I was

tuning."

Weiß's

musical style is, like that of

Bach, a German synthesis of

the French and Italian

baroque styles. Weiß was

doubtless familiar with suites

by the great French baroque

lutenists Gaultier, Gallot, Mouton,

and so forth, and with the

modified French music composed

during the late 17th century

by the German lutenists Esaias

Reusner,

Jakob Büttner,

and Philip Franz LeSage de Richée.

From them, and perhaps more

directly from Count Losy, Weiß

adopted the dance suite. In

Italy, and doubtless also

through the influence of the

Italian musicians at the

Dresden court, Weiß refined

his style, adopting cantabile

elements, increasing the force

of harmonic propulsion, and

extending the length of most

sonata movements. The result

is an individual style that

nonetheless sounds much like

Bach’s, although the two

greatest masters of their

respective instruments

probably did not meet

personally betore

1720 (one documented meeting

at Bach’s house in Leipzig

took place in 1739) and had

little apparent influence on

each other.

Most of

Weiß’s music is arranged in

the form of dance suites,

which in his manuscripts are

always referred to as Suonaten

or Partien. The order of

movements in the sonatas is

typically the following:

prelude (optional), allemande,

courante, bourrée,

sarabande, minuet,

gigue or allegro, but

substitutions for one or more

of the movements occur

frequently. Some pieces - two

tombeaux, a variety of

fantasias, and so forth -

appear to have been conceived

independently of the sonata. A

few four-movement sonatas for

lute and bowed strings also

survive, but unfortunately all

are missing the string parts.

Weiß’s career can be divided

into three major periods of

activity, with respect to the

development of his style.

The early period extends to

about 1715, when he returned

to Germany from Italy. The

middle period documents his

activity during his first

years in Dresden, until about

1725, and is characterized by

strong influx of the

Italianate elements enumerated

above. Approximately fifteen sonatas

survive from the last twenty-five

years of Weilß’s life, and in

them he continued to refine

the style of his middle

period. The music on the

present recording is

representative of the best

works of the middle period.

The Sonata in D minor

was

probably composed in Dresden

in the early 1720’s,

perhaps partly for pedagogical

reasons, since a note in a

student`s hand of Weiß’s

autograph manuscript

indicates: “This was the first

partita I

learned with Monsieur Weiß".

The prelude is unbarred but

falls neatly into phrases in

common time. The running

sixteenth-note figurations

essentially constitute a long

sequence of broken chords, not

unlike the first prelude in Bach’s

Well-Tempered

Clavier.

In

the allemande, by contrast,

the emphasis is less on

harmony than on the

languishing melody; this piece

is really an aria for lute.

The courante and bourrée are

again more instrumental in

character, both vigorous

dances designed to provide

momentum between the more

solemn allemande and

sarabande. The two minuets,

here played as a single minuet

en rondeau, are quick,

lighthearted movements, the

sarabrindc contemplative, and

the gigue a rollicking

finale.

One of the most hauntingly

beautiful pieces in the entire

history of lute music is the Tombeau

on the Death of Count Losy.

Count Jan Antonín Losy

von Losinthal (1650-1721) was

a landed Bohemian aristocrat

of Austrian heritage, an Imperial

Court Chamberlain, and the

most highly respected German

baroque lutenist before Weiß,

Weiß had undoubtedly met Losy

personally in Vienna or

Prague, and may have studied

with him for a time in his

youth.

As a tribute to Losy upon his

death, Weiß conceived

a piece in the key of B-flat

minor, an unusual and

difficult key

on the lute because of the

many barres it necessitates at

the first fret. The wistful

character of this tombeau is

established by means of

frequent diminished seventh

chords and other dissonances,

and by the slow pace. A

particularly elegiac effect is

created by the bass pedal

point at the verybeginning and

by other repeated notes, which

are obviously intended to

suggest the tolling of funeral

bells.

The C minor prelude on

this recording is one of

Weiß’s boldest experiments in

shocking harmonies and

chromaticism. It

seems to have been composed

about 1720, although in style

it more resembles music

written nearly a half-century

later. The autograph

manuscript of this prelude,

from which Hopkinson Smith

plays, is sketched out

rapidly, which implies that it

may represent an improvisatory

composition. This impression

of improvisation is supported

by the predominance of very

free, irregular rhythms

reminiscent of the

17th-century French unmeasured

prelude. Weiß here

makes unusually extensive use

of the diminished seventh

chord, an ambiguous harmony,

and includes a long passage

based upon a cleverly

disguised chromatically

descending octave in the bass.

The mood created by these

devices is unsettling, almost

schizophrenic, and is very

atypical for Weiß and late

baroque music in general. By

contrast, the Fantasie in

C minor that follows is

much more conventional in

conception. The first half

consists of even, arpeggiated

figurations in the manner of a

prelude, and the second half

of a fugato with a long,

sequential episode between the

entries of the theme.

The present Sonata in D

major is comprised of

various movements from the

Weiß manuscript in the British

Library. The prelude, like the

others on this recording, is

unbarred, with passages of

running arpeggios alternating

with block chords over a pedal

point. The Aria is another

allemande with strongly vocal

characteristics, its long,

spunout melody full of pathos

and frequent sigh figures. The

courante is like a movement

from a Vivaldi concerto in its

rapid figurations and

relentless forward propulsion.

Like the allemandes on this

recording, the D major

sarabande is operatic in

inspiration, with pathetic

sigh figures and a few

virtuoso flourishes. The

passagaille (passacaglia)

consists of a theme and eleven

variations, of which the last

is a slightly more ornate

version of the theme. The bass

remains the same in all

variations, but the melody is

transformed by elaborate

embellishments. A particularly

ingenious feature of this

passacaglia is the length of

the theme - an uneven seven

measures; the first measure of

each successive variation is

at the same time the last

measure of the preceding one,

thereby filling it out to a

total of eight. A lively gigue

provides an appropriate

finale.

Douglas

Alton Smith

The Widhalm lute is similar to

an aged aristocratic

general, the hero of battles

long since fought, still with an

elegant and proud bearing, but

also, no longer the tactician

he once was. The strengths of

the instrument - apart from

the amazing phenomenon that it

has survived in playing

condition without restoration

- lie in its wonderfully rich

bsss

register and in the clear

singing quality of the upper

strings (the first five

courses were strung in gut for

this recording). Less strong

qualities include a middle

register with less power than

it probably had originally and

also a mild stubbornness on

the part of the instrument in

lighter movements whose agile

passagework could have been

more clearly realized on a

more flexible modern

instrument.

The decision on my part to use

an original instrument does

not come from

any self-righteous assertion

that the music of a

particular period is

“supposed” to sound in one

specific way and that we

must therefore adhere to

burdensome “rules” of a time

and style. It

comes rather from, first of

all, a natural curiosity to

see what old instruments are

like - so few are in

playable condition and they

can normally be borrowed

only for a specific project

- and secondly, the desire

to see just how this

instrument and this music

would adapt to each other.

This project remains as much

a document of a magnificent

18th century lute (the first

to be recorded, I believe)

as it is a testament to the

greatest 18th century

Iutenist composer.

Three notes on the

programming:

1) In the Dresden Weiß Manuscript

version of the D minor

Suite, what is here

played as a minuet en

rondeau is copied out

as two distinct Minuets

separated by the Sarabande.

I have chosen rather to make

one more substantial piece

out of the two and to build

n more dramatic pacing into

the suite by pairing the

Sarabande with the Gigue.

2) The Prélude

and Fantasy in

C minor are also

separated in the British

Museum Weiß

Ms from

which they come,

but are here combined. Out

of the turmoil of harmonic

instability of the Prélude,

enters the unmeasured but

more stable opening of an

old friend, the C minor

Fantasie, one of the

best known lute pieces of

Weiß.

3) The last suite is a

regrouping of some of the

best pieces in D major from

different parts of the

British Museum Ms. Despite

their dispersion in the

manuscript, there are

thematic similarities

between the movements

(especially the Aria

and Sarabande), and

they fit together into a

well proportioned suite.

Hopkinson

Smith

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|