|

1 LP -

1C 065-30 943 Q - (p) 1978

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26512 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63067 2 - (c) 1989 |

|

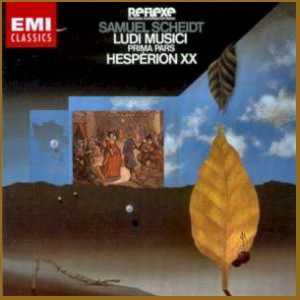

| SAMUEL SCHEIDT (1587-1654) -

Ludi Musici (Prima Pars) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Paduana,

Galiarda, Courante, Alemande, Intrada,

Canzonetto, ut vocant, quaternis &

quinis vocibus, in gratiam Musices

studiosorum, potissimum Violistarum

concinnata unà cum Basso Continuo.

Hamburgi Anno M. DC XXI |

|

|

| - Intrada

(XXIII) a 5 - Bläser,

Viole da gamba, Cembalo, Theorbe,

Trommel, Tambourin |

4' 10" |

|

| - Paduan (V) a 4

- Viole da gamba, Cembalo |

5' 12" |

|

| - Galliard

(XXIV) a 4 - 2 Flöten,

Viole da gamba, Cembalo |

1' 36" |

|

| -

Courant (XVII) a 4 - Viole

da gamba, Cembalo |

1' 35" |

|

| -

Paduan (VI) a 4 - Viole

da gamba, Bläser, Orgelpositiv |

5'

12"

|

|

| - Galliard

Battaglia (XXI) a 5 - Bläser,

Viole da gamba, Orgelpositiv,

Gitarre |

4' 09" |

|

| -

Alamande (XVI) a 4 - Viole

da gamba, Cembalo |

1' 36" |

|

| -

Canzon ad imitationem Bergamasca

Anglica (XXVI) a 5 - Bläser,

Viole da gamba, Orgelpositiv,

Theorbe |

5' 09" |

|

|

|

|

| - Canzon super

"O Nachbar Roland" (XXVIII) a 5

- Viole da gamba, Cembalo, Laute |

6' 09" |

|

| - Courant (XI) a

4 - Flöte, Viole da gamba,

Gitarre |

1' 25" |

|

| - Courant

(XIII) a 4 - Viole da

gamba |

1' 25" |

|

| - Canzon Cornetto (XVIII) a

4 - 2 Zinken, 2 Sopran-Viole da

gamba, Cembalo |

3' 18" |

|

| -

Paduan (III) a 4 - Bläser,

Orgelpositiv, Violone |

4' 23" |

|

| -

Galliard (XXV) a 5 - Viole

da gamba, Bläser, Violone,

Cembalo, Laute |

3' 10" |

|

| -

Courant (XVII) a 4 - 2

Flöten, Viole da gamba, Cembalo |

1' 43" |

|

| -

Canzon super "Cantionem Gallicam"

(XXIX) a 5 - Viole da

gamba, Bläser, Orgelpositiv, Laute |

5' 13" |

|

|

|

|

| HESPÈRION XX |

|

| -

Jordi Savall, Diskantgambe |

|

| -

Christophe Coin, Diskant- und

Altgambe |

|

| -

Ariane Maurette, Tenorgambe |

|

| -

Masako Hirao, Sergi Casademunt,

Roberto Gini, Baßgambe |

|

| -

Pere Ros, Violone |

|

| -

Bruce Dickey, Jean-Pierre Canihac, Zink |

|

| -

Jean-Pierre Mathieu, Alt- und

Tenorposaune |

|

| -

Charles Toet, Tenorposaune |

|

| -

Richard Lister, Baßposaune |

|

| -

Jeanette van Wingerden, Sopran-

und Altblockflöte |

|

| -

Lorenzo Alpert, Gabriel Garrido, Sopranblockflöte |

|

| -

Colin Tilney, Clavicembalo und

Orgelpositiv |

|

| -

Hopkinson Smith, Laute, Gitarre

und Theorbe |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Evangelische

Kirche, Séon (Svizzera) - 21-24

febbraio 1978 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 065-30

943 Q - (1 lp) - durata 57' 07" -

(p) 1978 - Analogico

(Quadraphonic) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63067 2 - (1

cd) - durata 57' 07" - (c) 1989 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26512 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 57' 03" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

SAMUEL

SCHEIDT SAMUEL

SCHEIDT

In

1620, Markgraf Christian

Wilhelm von Brandenburg,

administrator ot the

Archbishopric of Magdeburg in

Halle, appointed his court

organist Samuel Scheidt

(1587-1654) to the post of

director of music at court.

Soon afterwards Scheidt

published a collection of

instrumental pieces, since

“some of them have been

brought out in secret and

against my wishes”, those

pieces moreover having been

altered. The printed edition

contains 32 pieces of richly

imaginative instrumental

music. In

the years 1622, 1625 and 1627

Scheidt published further

volumes of the official

repertoire of the court

chamber orchestra, this music

now being known as Ludi

musici (musical

games). Unfortunately, with

the exception of one of the

basso continuo

voices, this music has

disappeared. Each piece in

the first volume is

dedicated to a musical

friend at the court or to

one of the court orchestral

musicians. The order, style

and tonality of the music in

Scheidt’s collection is only

to be fully understood in

the light of the strong

influence of English

instrumental music, namely

that ofthe English Consort.

He himself hinted at this

influence in the title of

No. 26, Canzon Bergam.(asca)

Angl.(ica)

and this same influence can

be seen quite clearly in

other pieces. The Markgraf

was related through the Duke

of Braunschweig to the

English King, James 1st.

The famous English virtuoso

viola player William Brade

visited Halle in 1618. The

title of Scheidt’s work

which rather clumsily lists

the varied contents is

similar to a large extent to

that of Brade: New,

selected Pavanes,

Galliards, Canzonas,

Allemandes and Courantes

(1609), and also to that of

the English composer Thomas

Simpson: An opus of new

Pavanes, Galliards, Intradas,

Canzonas... Allemandes,

Courantes (1617).

Simpson was a viola player

in Copenhagen in the court

orchestra of the Danish king

who was an uncle of the

Regent in Halle. Scheidt’s

collection was published by

Michael Hering in Hamburg,

as had been the works of

Brade and Simpson.

The Ludi musici

contain two kinds of music:

dance pieces and free

instrumental pieces. The

dances, as they are listed

in the title: Pavanes

(6), Galliards (5),

Courantes (10) and Allemandes

(3), are arranged in

consecutive groups. Scheidt

does not arrange them in the

cyclic form of a Suite, as

does Brade in 1609, or his

Leipzig friend Johann

Hermann Schein in 1617 in Banchetto

musicale. He even

ignores the conventional

practice of varying the

material of the Pavane

to form the ensuing Galliard

which is its partner. The

variation on a model

movement was used by

Scheidt, but usually in

dances of a similar type:

take, for example, the Courante

No. 17, of which the

variation, No.32 (ad

imitationem Courant 17)

forms the end of the work. A

further example is the Galliard

No. 24 which is a

five-part version of the

four-part Galliard No. 7.

The different, highly

artistic design of the

individual dance movements

by Scheidt reflects the

stage of development of

dance music and concert

music. The Allemande and the

Courante have only two

repeated parts, and these

parts in themselves show

little musical development.

The Allemande has the

character of a functional

dance-piece

through its song-like melody

and clear 4

and 8-bar phrases; on the

other hand the increasingly

polyphonic nature of the

second half is evidence of

the English characterisation

of this dance which contrasts

with the compact, plain form

of the German type which is

simply called Dantz.

The old French court dance Courante,

which was first introduced

into Europe around 1600, and

which was characterised by its

buoyant 3/4 or 6/4 time, has

similar dance-like features,

for example, in the five-part

No.23, where short melodic

parts are linked tonally by

means of a second high part

written a third below the

first part. For the most part

the Galliards retain their

rhythmically profiled, 3/4

time, dancelike character,

full of courtly grace. All three

parts of No. 25 have the even

phrasing of 16 bars which

corresponds with

dance-figures. In No.24, the

dance rhythm is also

emphasised by, for example,

repeated notes, however, the

plain melodic phrases of the

model (No. 7) are transformed

into virtuoso figures and

divided in alternating fashion

between two high solo parts.

This alternating between parts

is expanded in the third

section of the Galliard No. 25

to achieve the effect of two

juxtaposed instrumental

forces, over the fundamental

structure of a diatonically

ascending bass part. In No. 21

the alternating use of two

instrumental groups is

exploited programmatically in

a Galliard Battaglia.

The close succession of one

motif upon another, their

rivalry and final union in

excited momentum bears witness

to the genre of “musical

battle” which had been so

popular since Janequin’s

chanson La Bataille

(1530), The work Battle

Galliard by John Dowland

(1604), dedicated to the

Danish king, was the direct

model for Scheidt’s work which

is typical in its ideas, with

rhythmically emphasized

repetitive notes, slow-moving

harmony and fanfare-like

motifs, Scheidt took Dowland’s

original thematic concept in Battle

Galliard and expanded it

fourfold in his own work. He

also rewrote it for Clavier

under the title Galliard

Dulenti variirt.

The process of stylisation

which can also be observed in

the other dance movements

reaches a final stage in the

Pavanes which open Scheidt’s

collection. The framework of

dance music is finally broken.

Serious and solemn in

expression, intricate and

tightly woven, built in three

larger parts, they follow the

type of the English Pavane,

as V. Haussmann explicitly

called them in 1604. They can

only be called Pavanes in so

far as they are characer

pieces. Otherwise they already

breathe the spirit of the free

instrumental canzone. This is

shown, for example, in the

homogeneous thematic material

moving in seconds in the

manner of the old classical

vocal polyphony at the

beginning of Nos. 3 and 5, or

in the constructive conception

of the bass in the lamentoso

steps in chromatic fourths in

No.5 (Part II).

The cantus-firmus type octave

passage in No.6 (Part III)

reminds us, when it transfers

to the upper voice, of

Monteverdi's Sonata

sopra Sancta Maria

(1610). Thus the Pavanes, with

their intricately constructed

voices, their imitation and

filigree work present an

example of the highly

developed English chamber

music of the Consorts.

In

spite of the fact that Scheidt

did not put the single

five-part Intrada (No.

22) at the beginning, it

preserves, beyond its possible

function as a processional

march, the character of a

festive opening music in C

major. Scheidt’s work

anticipates the duo

concertante sonata form which

was composed, for instance, by

the Vienna Director of Court

Music, J.H.Schmelzer, around

1660. In the 2nd part two

soloists compete in three-part

chord figures derived from the

wind motifs which are extended

in Part III

also to a bass part. This

baroque trio form is

accompanied by standing notes

on the other instruments. Thus

the Intrada could

also be performed without the

continuo part as open-air

music. The Intrada has

an additional section in the

more lively 6/4 time. This was

derived from the habit of

dance musicians of playing

improvised versions of 2/4

dances in three time. The Pavane

No. 3, for instance, has

such a Nachtanz (added

dance) in the so-called Proportion

(proportia tripla).

This rhythmic modification was

formalized about 1600 in

paired movements

like Pavane-Gulliard

and Allemande-Courante.

Scheidt did not use these

pairs, but artfully used

this contrast of duple and

triple times in the non-dance

orchestral pieces, the

Canzones.

Sizewise the six large

Canzones make up an entire

half of the collection. They

are instrumental pieces

based on vocal themes, as

Scheidt states himself. All

three instrumental Canzones

very distinctly show English

influence. The Canzon ad

imitationem Bergamasca

Anglica consists of

variations on a typical

dancing song from Bergamo in

Northern Italy which was

known all over Europe; for

instance, it was wittily

quoted by Bach in his Goldberg

Variations from the Augsburger

Tafelkonfekt of 1733

where it had the text “Kraut

und Rüben”. Scheidt keeps to

the melodic form of the

English virginal players

Giles Farnaby and John Bull

which was also used by his

teacher Sweelinck. “Oh,

neighbour Roland” was

a melody very popular in

England - William Byrd among

others composed a piece for

the virginal around it. In

1603 it was found in Ph.

Hainhofer's

Lute Tabulature “A Song of

English Players performed

here", which since Franck’s

Quodlibet of 1611 became

part of the German folksong

repertoire as “Rolandston”.

The Canzon super Cantionem

Gallicam

ses a widely

known melody, the one of “Est-ce

Mars”, the

impudent chanson of the

victory of Amor over the God

of War, Mars. Scheidt himself

followed up the Clavier

variations by his teacher

Sweelinck in 1624 with ten

variations in his Tabulatura

nova.

Out of the tension between

popular melodies and most

elaborate five-part

arrangement Scheidt created a

completely new type of

canzone. Admirable is the way

in which Scheidt builds a

spacious and varied piece from

the two-bar

phrases of the

Bergamasca-melody. The

construction of the setting is

“English” (Anglica)

with imitation and most

elaborate fugues including

stretto, canonic writing and

double counterpoint. Already

in 1604 V. Haussmann

had rewritten the Rolandslied

as a “Fuga” for the Hamburg

musicians. Added to this three

are the variations of the

theme itself, also in

expansion and contraction.

Particularly drastic, however,

is his changing of the rhythms

into triple time which is at

the same time an effective

means of achieving contrasting

expression. As in the Canzone

on “Est-ce Mars",

sections in animated dancing

rhythms in triple time are

found at the end of each of

the three parts, making the

subdivisions of fugues and

variations of the three

melodic sections transparently

audible. The Canzon

Bergamasca is conceived

formally from the contrast of

the lyrical first half of the

theme and the playful and

lively one of the second. Four

different fugal statements of

the first half are each

contrasted with concertante

sections on the second half of

the theme. After the fourth

part in changed bar time, with

its cantus-firmus-like

transformation of the theme,

the shortened return of the

first part completes the basic

structure.

The Canzon Cornetto on

the other hand makes use of

the typical rhythms of the

Italian Canzona. The

stipulation “Cornetto”

(cornet) refers to the cornet

player Zacharias Hartel from

Halle to whom the Galliard

Battaglia (No.21) is

dedicated. This brings us to

the question of the tonal

realization. The written music

only gives the structure of a

piece; neither instrumentation

nor dynamics and phrasing are

fixed, but offer many

possibilities of

interpretation. The liberal

attitude of the time also

permitted improvisation around

the written notes, manifold

repetition of single parts,

etc.. The title designates the

pieces as particularly for

viol players, as this had

become accepted in Germany

since Brade and Simpson. But

Scheidt expects wind-players

not only for the two pieces

for cornet, Nos.18 and 21. In

the title of the second part

of Ludi musici Scheidt

states that the pieces are

optionally to be played on “4

violas da Gamba, 4 trombones,

4 bassoons, but also on

cornets”. Further the

repeating and alternating of

motifs and figures suggest

different types of

orchestration already by the

nature of the composition,

partly in the form of two

concertante

juxtaposed instrumental

groups. The musical structure,

by means of temporary shifting

of the lower voice into the

tenor as Bassett in Nos.11

and 16 is also a special sound

texture, as is the string

tremolo at the climax of the Roland’s

Canzone, The use of the

bass continuo gives the Ludi

musici thetraditional

character of chamber music.

In the

tension between stylised

society dance and artistic

concert music the Ludi

musici were used at many

different functions, as table

music and generally “for happy

recreation of the heart”

(Simpson 1610).

Klaus

Wolfgang Niemöller

Translation:

P H. Linnemann

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|