|

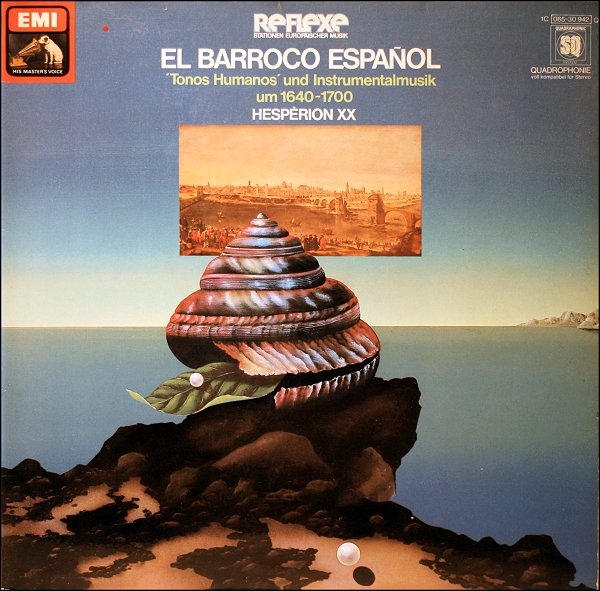

1 LP -

1C 065-30 942 Q - (p) 1978

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26511 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63418 2 - (c) 1990 |

|

| EL BARROCO ESPAÑOL - "Tonos

Humanos" und instrumentalmusik um

1640-1700 |

|

|

|

|

|

| "TONOS

HUMANOS" a solo con instrumentos |

|

|

| - Deza la aljava

(Ayroso) (De Milanes, 17 Jh.)

- Gesang, Clavicembalo,

Guitarra, Viola da gamba, Basse de

Violon |

3' 12" |

|

| - Aquella Sierra

Nevada (Passacalle a solo)

(José Marin, 1619-1699) - Gesang,

Guitarra, Viola da gamba, Basse de

Violon |

2' 41" |

|

| - Peynandose

estava un olmo (Juan Hidalgo,

1612-1685) - Gesang,

Clavicembalo, Viola da gamba |

1' 44" |

|

| -

Diferencias sobre las Folias

(Antonio Martin, 2. Hälfte des 17.

Jh.) - Viola da Gamba, Guitarra |

6' 47" |

|

| -

La Chacona (Antonio Martin,

2. Hälfte des 17. Jh.) - Viola

da gamba, Clavicembalo, Basse de

Violon |

5'

12"

|

|

| - Canarios (Antonio Martin, 2.

Hälfte des 17. Jh.) - Viola da

gamba, Guitarra |

0' 37" |

|

| "Tonos

Humanos" |

|

|

| -

Atiénde y da (Juan Hidalgo,

1612-1685) - Gesang, Tiorba,

Viola da gamba, Clavicembalo |

2' 59" |

|

| -

Ay Corazón amante (Juan

Hidalgo, 1612-1685) - Gesang,

Clavicembalo, Guitara, Viola da

gamba, Basse de Violon |

3' 36" |

|

|

|

|

| "Solo Humanos" |

|

|

| - Sosieguen, Descansen

(Sebastián Durón, 1660-176) - Gesang,

Viola da gamba, Tiorba, Clavicembalo,

Basse de Violon |

5' 20" |

|

| - Tocata und Gallarda

(Juan Cabanilles, 1644-1712) - Clavicembalo |

8' 06" |

|

"Tonos Humanos" a solo

|

|

|

| - Con tanto respecto adoran

(Juan Hidalgo, 1612-1685) - Gesang,

Clavicembalo, Guitarra, Viola da gamba |

2' 34" |

|

| - No te

embarques pensamiento * (Del Vado, 2. Hälfte des 17.

Jh.) - Gesang, Clavicembalo,

Viola da gamba, Guitarra |

2' 33" |

|

| - Ay

que me rio de amor * (Juan Hidalgo, 1612-1685) - Gesang,

Clavicembalo, Viola da gamba |

1' 53" |

|

|

|

|

| * mit

frendlicher Genehmigung der "Hispanic

Society of America" |

|

|

|

|

|

| HESPÈRION XX |

|

| -

Montserrat Figueras, Gesang |

|

| -

Jordi Savall, Viola da gamba |

|

| -

Ton Koopman, Clavicembalo |

|

| -

Hopkinson Smith, Guitarra und Theorbe |

|

| -

Christophe Coin, Bass de Violon |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Evangelische

Kirche, Séon (Svizzera) - 10-16

settembre 1976 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 065-30

942 Q - (1 lp) - durata 47' 53" -

(p) 1978 - Analogico

(Quadraphonic) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63418 2 - (1

cd) - durata 47' 53" - (c) 1990 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26511 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 47' 53" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

EL BARROCO

ESPAÑOL EL BARROCO

ESPAÑOL

Spanish music

flourished in the 17th

century, yet only now, after

two centuries of neglect, are

we beginning to realize the

greatness of this music.

Throughout the Iberian

peninsula Spanish composers,

singers and instrumentalists

have always enriched the lives

of their people, but so

popular was the music of the

17th century that it was

copied outside Spain in Italy,

France, Holland, England and

even America.

While not the only place, the

court in Madrid was the focal

point of this musical activity

from the beginning of the 17th

century. The capilla real

included 30 or 40 men who

sang, composed or played

keyboard instruments, the

harp, the “violon” (viola da

gamba), the violin, and

various wind instruments. It

provided music for all

religious and nonreligious

occasions at court, sometimes

supplemented by city musicians

from Madrid and elsewhere

inthe realm; and it also

assisted at municipal

festivities outside court

whose magnificence required

the skills and numbers of the

best musical group in Spain.

There were also gifted

musicians at the two chief

royal monastery-convents:

Descalzes Reales and

Encarnacion. Men of much

simpler outlook and ability

served the five Madrilenean

parroquial churches, several

other monasteries, and the

city. Outside Madrid elaborate

capillas were to be found in

Cathedrals and monasteries in

such places as Valladolid,

Segovia, Burgos, Palencia, El

Escorial, Barcelona, Valencia,

Seville, etc..

Religious music dominated.

Besides Latin liturgical

pieces there were primarily

the countless villancicos, and

Spanish sacred organ music

reached new heights in the

hands of Correa de Arajo (c.

1575-1654) in Jaen and Seville

and Cabanilles in Valencia.

But there was also much

secular music. The tono

humano (secular song),

which often was intended to be

sung as part of a zarzuela or

opera, consists of a series of

stanzas (coplas) sung

to the same music; usually

there is also a refrain (estribillo)

which precedes and follow each

copla. Most tonos are

for one voice with

accompaniment of basso

continuo (lute, harp, guitar

or harpsichord with violon)

and occasionally obligato

instruments (violin, oboe).

Early in the 17th century,

however, secular songs are

usually polyphonic vocal

pieces (romances, letras and

other poetic types), collected

in cancioneros, or guitar

pieces with improvised vocal

lines. They customarily have

instrumental ritornellos

(frequently termed pasacalla,

folia, ruggiero, or chacona),

a practice which was less

common in the second half of

the century. Only in the

middle of the century did the

classical tono humano

as described above begin to

appear, and it is this song

which is represented in this

recording.

One of the most popular

composers in the 17th century

in Spain was Juan Hidalgo. A

member of the capilla real

from about 1631 until his

death in 1685, he was

primarily a harpist and

harpsichordist. As a composer

he attained considerable fame

for his tonos humanos

and for his dramatc music. He

worked closely with Calderón de

la Barca, the principle

mid-century court poet and

dramatist, with whom Hidalgo

helped create the earliest

Spanish operas c. 1600. In the

operas Hidalgo incorporates

the Italian recitative style

as well as more traditional

strophic arias and choruses.

For the Spanish Queen Mother’s

birthday on December 22, 1672,

Hidalgo composed music for

Juan Vélez

de Guevara`s “Los celos hacen

estrellas”, which may be the

earliest zarzuela whose music

survives intact. The five tonos

humanos on this

recording are typical of

Hidalgo’s music. On the one

hand the short “Ay que me rio

de amor" (3 coplas and

estribillo) is

folklike: triple dance rhythm

with hemiolas, small range,

syllabic. On the other hand

the long “Ay Corazon amante"

(6 coplas and estribillo)

is Italianate:

ornate runs that paint the

words “exciting the sea into

waves" (alborotado el mar

en olas).

“Con tanto respecto adoran” (5

coplas and estribillo),

“Peynandose estave un olmo”

(only 1 copla and the

estribillo survive),

and “Atiénde y da” (6 coplas

and estribillo) have

considerable motivic

development that demonstrates

Hidalgo’s artistic virtuosity.

Few musicians can claim the

notoriety that surrounds the

name of José Marín,

perhaps the greatest Spanish

song writer. Born c. 1619, he

was an ordained priest serving

in the Encarnacion Monastery

when, in 1654 and again in

1656, as legend has it, he was

imprisoned, accused ot robbery

and several murders, whipped,

unfrocked, and banished from

Madrid for ten years (the last

sentence of which was not

completely carried out since

he was again in Madrid in

1657). Little else is known

about him, but he was

sufficiently worthy to merit

an obituary in the Gaceta

de Madrid on March 17,

1699, where his age is given

as 80 and it is stated that he

was “known in and outside

Spain for his rare skill in

composition and performance.”

All Marín’s

surviving works are tonos

humanos, about 60 for

one voice and two for two

voices, accompanied by guitar

or basso continuo. “Aquella

Sierra Nevada” survives in two

versions. The one used here is

for solo soprano accompanied

by a guitar of 5 strings

(Fitzwilliam Ms.);

it has 6 coplas with an

instrumental ritornello at the

end of each copla,

and there is no estribillo.

The other version is a duo for

soprano and tenor with basso

continuo accompaniment (Madrid

Bibl. nac. Mus.

3881, no. 33); it has no

ritornello but, in addition to

the 6 coplas, whose

soprano music is the same as

that in the Fitzwilliam Ms., it

does have an estribillo.

Marín

sings in glorious rapture over

the seasonal changes in

nature, “but in my sorrow

there is no change.” Juan del

Vado flourished in Madrid from

1660 to the 1680`s. He was

both organist and violinist in

the capilla real and

came from a family of

violinists (his brother

Bernardo joined the capilla

real as violinist

in 1648 and Felipe del Vado,

probably a relative and

wrongly identified as Juan by

some scholars, joined as

violinist in 1633). Although

famous as a composer of

secular tonadas during his own

lifetime, he is known today

for a large amount of sacred

music, principally in two

large manuscripts in the

Madrid Bibi. nac. His tonos

can be found in the

Cathedrals in Segovia and

Valladolid and in libraries

in Barcelona, Madrid, Munich

and New York. “No te

embarques pensamiento" warns

of the lure of Sirens, whose

voice and harmony can

destroy one. It

consists of two coplas

surrounded by an estrebillo.

“Dexa la aljava y las

flechas" by the unknown

composer De Milanes, is a

typical tono

with a long estribillo

and 4 coplas; it

also has a final refrain.

Syllabic except for a

poignant “Ay” in the estribillo,

it is addressed to Cupid,

the all-powerful one.

The last great maestro in

the 17th century capilla

real was Sebastián

Durón.

After a successful career as

organist in the Cathedrals

of Seville (1680-1685),

Burgo de Osuna (1685-1686)

and Palencia (1686-1691),

Durón

became the successor to José

Sanz as second organist of

the capilla real.

His fame as an organist,

however, was greatly

surpassed by his fame as a

composer of sacred vocal

music (archives in Spain,

Latin America and elsewhere

are full of these Latin and

Spanish works) and as a

composer of zarzuelas and

operas for the royal

theatre, of which he became

a director. In

1706 when Carlos II

was forced from the throne

of Spain, the loyalist Durón

was driven into exile in

southern France, where he

spent the remainder of his

life. He was a prolific

composer whose works

sometimes are traditional

Spanish types - semi-sacred

villancicos and tonos

humanos - but at

other times new Italian

types - cantatas resembling

those of Alessandro

Scarlatti with da capo arias

and recitatives. The latter

were often so florid that

his contemporaries

criticized Durón

for introducing too many Italianisms

into Spain, though surely

Hidalgo and others had

already made much use of at

least some recitative and

other Italian

devices. “Sosieguen,

descansen" is not so radical

a departure from Durón’s

Spanish predecessors’ music

for zarzuelas. It is

a segment of the comedia

héroica “Salir el amor

del mundo" (which may be the same

as the very early 1680

zarzuela “Venir el amor al

mundo"), a fiesta in two

acts (jornados) with

a preliminary loa,

performed before the king. It is

traditional in that it opens

and closes with an estribillo

and includes inbetween three

coplas; it is forward

looking in that it also

includes a dramatic

recitative after the three coplas

and before the return of the

estribillo.

The estribillo

uses expressive musical

intervals, especially a

downward leap. A change of

meter from duple to triple

distinguishes each copla

here from the traditional copla

which is in only one meter.

Juan Cabanilles was the

greatest Spanish organist

ofthe 17th century. Born in

Algemesí

(near Valencia) on September

5 or 6, 1644, he was

appointed first organist at

the Cathedral in Valencia in

1665, where he remained for

the rest of his life.

Apparently a condition of

his job was for him to

become a priest, for one

month after his appointment

he started working on minor

orders and was ordained on

September 22, 1668. He was

not only a famous composer

and performer in his own

time but also a highly

respected teacher. Pupils

came from all over Spain and

France, and some of them

helped fashion keyboard

styles in the 18th century.

Cabanilles’s surviving

compositions are almost

exclusively sacred keyboard

works, though there are

eight liturgical vocal works

(including a Mass) found

today in Valencia and

Barcelona. He wrote hundreds

of organ verses (i. e.,

organ arrangements of or

accompaniments to psalms,

hymns, Mass sections, the

Magnificat, etc.), 183

tientos, 6 toccatas, 5

galliards, pasacalles,

batalles, paseos and 1

corrente. The keyboard

instrument was probably

organ for most of these

pieces, but performance on

the harpsichord would have

been a likely option for any

of them and the likely

choice for the secular

galliards and corrente. The

two works performed here - a

toccata and a galliard -

demonstrate Cabanilles’s

extraordinary inventiveness

in harmony and figuration.

The short toccata is

basically homophonic; in two

sections, the first is with

simple elaboration of the

chords and the second, which

begins without any break, is

a faster, more complicated

elaboration, with rapid

modulations. The galliard is

in duple meter and thus has

no tie to the well-known

17th-century dance of that

name in triple meter. It is

along set of variations, far

exceeding the toccata in

complexity and intensity,

and it is one of

Cabanilles’s most brilliant

works.

Antonio Martin y Coll was

one of the leading Spanish

organists of the next

generation. He studied at

the Franciscan Monastery San

Diego in Alcalá de

Heneres where he also was

organist, and later he

served as first organist at

the Monastery San Francisco

el Grande in Madrid,

remaining there until his

death. He published five

large volumes of music,

mostly for the organ

(1706-1709). Volumes 1-4

contain almost 2000 works by

other, mostly anonymous

composers, and present a

good sampling of

17th-century Spanish organ

music. Volume 5 contains

Martin y Coll’s own works,

mostly verses. Not all the

works are intended for the

organ; volume 5 includes

Martin y ColI’s treatise on

keyboard instruments in

general and the harp, which

suggests that many of the

pieces might be performed on

any keyboard instrument or

the harp, and some

of the pieces in the earlier

volumes actually designate

other instruments.

Furthermore, it is possible

that the secular works such

as the three on this

recording would have been

just as appropriately played

on gamba, with harpsichord

or lute and violon as

sustaining instrument, as on

the organ. The first Diferencias

(variations) will

immediately remind the

listener of Corelli’s more

famous setting of the same

harmonic bass “La Folia".

The Chacone and Canary are

also harmonic bass patterns.

The Chacone is based on the

pattern G - F - E flat - D -

D - G. The Canary, taken

from a famous

late-16th-century court

dance, is the shortest of

the three variations; the

bass pattern is D - G - F

sharp - E - D.

John H.

Baron

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|