|

1 LP -

1C 065-30 941 Q - (p) 1978

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26510 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63417 2 - (c) 1990 |

|

| CANSÓS DE

TROBAIRITZ (Lyrik der Trobairitz, um

1200) |

|

|

|

|

|

Vos que'm

semblatz dels corals amadors

(Gualcelm Faidit, um 1150 - um 1220)

- (Dialog) Gesang, 2 Flöten,

Schlaginstrumente

|

3' 53" |

|

| - Text: Condesa de

Provenza (1200-1229) und Gui de

Cavalhon |

|

|

| Estat ai en greu

cossirier (Raimon de Miraval,

1191-1229) - (Cancó) Gesang,

Vielle, Lira |

6' 07" |

|

| - Text: Condesa de

Dia (um 1200) |

|

|

| Na

Carenza al bel cors avinen

(Arnaut de Maruelh, um 1195) - (Tensó-Cancó)

Gesang, Laute |

5' 51" |

|

| -

Text: Alais, Na Yselda i Na Carenza |

|

|

| Si us quer

conselh, bel'ami'Alamanda

(Guiraut de Bornelh, 1162-1199) - (Tensó)

Gesang, Vielle, Laute, Lira,

Guitarra moresca,

Schlaginstrumente |

9' 42" |

|

| - Text: Guiraut de

Bornelh (1162-1199) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ab joi et ab joven m'apais

(Bernart de Ventadorn, 1147-1170) - (Cancó) Gesang,

Flote, Vielle, Guitarra moresca,

Rebab, Schlaginstrumente |

5' 26" |

|

| - Text: Condesa de Dia (um 1200) |

|

|

| A chantar m'er de so q'ieu no

voldria (Condesa de Dia, um 1200) -

(Cancó) Gesang,

Lira |

8' 20" |

|

| - Text:

Condesa de Dia (um 1200) |

|

|

| S'anc

fui belha ni prezada (Cadenet,

1200-1230) - (Alba) Gesang, Flöote,

Laute, Guitarra moresca, Vielle, Lira |

10' 24" |

|

- Text: Cadenet (1200-1230)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HESPÈRION XX |

|

-

Montserrat Figueras, Gesang

(Nrn. 1-7)

|

|

| -

Josep Benet, Gesang (Nrn. 1, 4

und 7) |

|

| -

Pilar Figueras, Gesang (Nr. 3) |

|

| -

Jordi Savall, Vielle und Lira |

|

| -

Hopkinson Smith, Laute und

Guitarra moresca |

|

| -

Lorenzo Alpert, Flöte und

Schlaginstrumente |

|

| -

Gabriel Garrido, Guitarra

moresca, Flöte und

Schlaginstrumente |

|

| -

Christophe Coin, Vielle und

Rebab |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Evangelische

Kirche, Séon (Svizzera) - 7-9

giugno 1977 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 065-30

941 Q - (1 lp) - durata 50' 05" -

(p) 1978 - Analogico

(Quadraphonic) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63417 2 - (1

cd) - durata 49' 59" - (c) 1990 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26510 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 49' 58" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

CANSÓS

DE TROBAIRITZ CANSÓS

DE TROBAIRITZ

It was

on a spring day, I had just

finished my lecture at the

Barcelona University Institute

of Romance Studies, when two

visitors called, a gentleman

and a lady. He had a firm

voice and a penetrating eye,

she talked gently and had a

dreamy glance. They were Jordi

Savall and Montserrat Figueras

who had come with the

intention of adding some

troubadour-songs to their

already considerable

repertoires. Being artists

with a highly refined sense of

musical subtleties they had

not failed to see where the

problem lay: the love songs of

the troubadours are, naturally

the lyrical expression of a

man’s passion; consequently

they lose a certain quality

and give a somewhat oddly

artificial impression when

sung by a woman, the more so

if the singer is a soprano. (It is

true that the jongleurs are

supposed to have sung with

somewhat forced and extremely

highpitched voices, similar to

the countertenors of our day,

but this did not interfere

with their credibility: they

were men, and sang of a man’s

passion for a woman.)

Montserrat put the problem to

me right away: “Would it be

possible to fill a whole

long-playing record of over

forty-five minutes’ duration

solely with songs of the trobairitz?"

This is to say, with works of

some of the eighteen women

whose names have been handed

down to us - of only eighteen

of a great number of female

singers who, like their male

colleagues, used to practise

the art of trobar at

the courts of Western Europe.

My first professorial answer

was “no”. It

was not possible. Of the 236

surviving melodies of the

troubadours known to us, 43

different authors in all, only

one, namely A chantar m-er

de so q’ieu no voldria,

was written by a trobairitz,

the mysterious Condesa de Dia.

Therefore I

suggested something different:

a recording of songs of

Catalan troubadours, or a

selection of the most famous

works of that period, or of

such songs as had not yet been

issued on record. “Later...", they

replied with undisguised

disappointment. When Jordi and

Montserrat left me that day

they looked a little sad. So I made

up my mind to make the

impossible possible and try to

oblige them, but not

altogether for altruistic

reasons. I myself

had begun to be fascinated by

the idea of hearing women’s

songs from Occitania performed

after so many centuries of

silence, sung, too, by the

voice of a woman who had a

natural affinity to them, both

spiritually and geographically

- a Catalan singer. I had

the idea of taking full

advantage of the immense

possibilities which arise out

of the common medieval

practice of borrowing melodies

for a given piece of poetry.

This was a widely practised,

if little known custom (of the

2542 surviving works of the

troubadours, 514 are securely,

and another 70 in all

likelihood, reckoned to be

imitations of borrowings with

respect to their melodies).

Besides, I

intended to adopt the

legitimate method of having

the dialogic songs sung by two

vocalists, the part of the man

by a male voice, that of the

woman by a female one. Thus we

arrived at a total number of

seven compositions - the

record had been made possible,

and Montserrat and Jordi were

overjoyed. Together we made a

thorough study of the texts

(at German and Catalan

Universities they teach the

traditional pronunciation

which differs in some points

from the pronunciation common

in France), rehearsing began -

and here now is the result.

Three of the selected works

were written by the Condesa de

Dia, that mysterious woman who

is still a puzzle to the

scholars (whether she lived in

the late 12th or in the early

13th century, is

controversial). She was one of

the great poetesses of all

times, one of the women who,

with vehemence, passion and

veracity, have sung the

praises of carnal love. (Let

us call to mind that courtly

love as praised by the

troubadours was of an

essentially adulterous

character, and that the

Condesa herself was a married

woman.) Her Estat ai en

greu cossirier probably

used the melody of Lonc

tems ai agut

consiriers by Raimon de

Miraval (a troubadour who has

been proved to have lived

between 1191 and 1229). Ab

joi et ab joven

m’apais, which features

the by no means simple

technique of the rims

derivatius (derived

rhymes), was definitely

performed on the melody of Estat

ai com hom esperdutz of

the great Bernart de Ventadorn

(third quarter of the 12th

century). Finally, both the

text and the melody of A

chantar

m·er de so q’ieu no voldria

were written, according to the

cancioners, by the Condesa de

Dia herself.

Vos que·m

semblatz dels corals amadors

is a short tenson (poetic

dialogue) or, more accurately,

a dialogic sequence of two

simple coblas

or stanzas. The first was

written by the Condesa de

Provenza Garsenda, the wife of

Count Alfonso II (established

between 1193 and 1215), the

second by the troubadour Gui

de Cavaillon (first quarter of

the 13th century).

As a rule this type of lyrical

dialogue would borrow the

melody of a popular and widely

known canso. In this

instance the source of origin

of the melody was Jamais

nul tems no·m

pot ja far Amors by the

Troubadour Gaucelm Faidit from

Limousin (established between

1172 and 1203).

Na Carenza al bel cors

avinen is a rather

peculiar tenson between two

sisters (or nuns?), N'Alais

and Na Yselda, who in our

version sing the first stanza

and the repeat together and in

unison, and Na Carenza who

sings the second stanza alone.

The two sisters enquire

whether marriage would be

advisable, giving a precise

description of the

consequences. Na Carenza

earnestly advises them to

enter a convent. The melody

used here is the very famous

tune of La grans beutatz

e·l fis

ensenhamens of which no

less than eighteen melodic

imitations have been handed

down to us - a clear testimony

to the lasting success and

great popularity of this canso

by Arnaut de Maruelh, a

troubadour from Périgord

(last quarter ofthe 12th

century).

Si us quer conselh,

bel'ami' Alamanda is one

of the most famous

compositions of Guirot de

Bornelh from Limousin whose

literary activities have been

established between 1162 and

1199. The piece under notice

is a tenson or

dialogue between the

troubadour and Alamanda, the

maid of his adored one. He

insists that she should bring

about a reconciliation between

him and her lady. Everything

indicates that this tenson is

fictitious and serves merely

as a literary pretext which is

worked out with great charme

and a good deal of irony. The

music is by Guirot himself

(which would not have been the

case, had the tenson

been an authentic dialogue)

and was widely used and

frequently imitated by other

troubadours.

S’anc fui belha

ni prezada by Cadenet

(first third of the 13th

century) is one of the most

famous albas (morning

songs) ever written; its music

was even borrowed for one of

the cantigas of King

Alfonso X the Learned. It is a

dialogue between a lady (first

and last stanzas) who

complains about her husband

and declares that she intends

to stay with her lover until

dawn, and the guardian over

her love (second, third and

fourth stanzas) who assures

her of his faithful services

while she is with her lover.

Francisco

Noy

Translation: Jürgen

Dohm

How the

Troubadour songs were handed

down

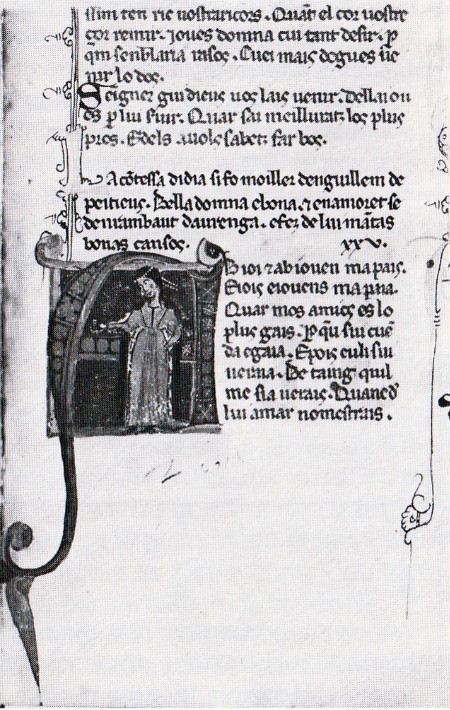

Only in four of the

approximately 30 Troubadour

manuscripts of the 13th and

early 14th centuries a part of

the contents has been handed

down with Troubadour

manuscript could have at his

disposal originate on the one

hand in the medieval chorale

and on the other hand in the

polyphony which developed from

this - this latter had its

centre in Paris, i. e. at some

distance geographically and

culturally speaking from the

‘Lebensraum’ of the

Troubadours. Music which has

developed and has been handed

down through oral tradition

only is not easily written

down in a system of notation

whose symbols have been formed

through confrontation with a

different type of music and

unavoidably reflect its

characteristics. This is what

happened with the Troubadour

songs. The situation becomes

even more difficult if one

assumes that the Troubadour

melodies are foreign to the

written down repertoire and

are subject to other - such as

Spanish and Arabic -

influences. This would produce

an additional conflict: music

which - as we must assume -

was subject to other rules and

conventions than the ones of

Northern France might possibly

have had striking qualities

such as details of voice

production (for instance

different types of guttural

sounds) or other tonalities

would be impossible to

reproduce within the

conventions of notation of

that period. The many empty

staves in the manuscripts are,

as it were, a reflection of

this conflict.

Under these circumstances the

existing melodies for the

Troubadour poems are only

those which were close to the

repertoire which was "writable"

(i. e. the chorale and the

music of Notre-Dame), or those

which, through the process of

writing down with such

notation methods, were adapted

and therefore modified. Each

musical source therefore

reflects the particular

situation of a melody which

consists in the fact that it

has been written down at all;

it stabilises the melody in a

form which could possibly be

very different from the

different ways in which it was

previously sung and which were

never written down.

It is further possible that

the linking-up

of the text and music could

sometimes only take place at

the time of writing down; this

suggests itself when we

consider the A chantar m·er

de so q’ieu no voldria

of the Condesa de Dia (No.6).

This poem is recorded with

melody in Manuscript W, a

manuscript containing mostly

Trouvere-songs which came into

existence about 100 years

later than the songs of the

Condesa (1150-1175). In this

version the Provencal

poem shows French influences.

In this case only the change

of the end syllable -ens

in the last lineto -ence

is important and with it the

resulting change in the number

of syllables:

A chantar

m·er

deso q’ieu no voldria,

tant

me rancur de lui

cui sui amia

car

eu l’am mais que nuilla ren

que sia;

vas

lui

no·m

val merces ni cortesia,

ni

ma beltatz,

ni mos pretz,

ni mos sens,

c’artressi·m

sui enganad’e trahia

cum

degr'essen

s’ieu fos desavinens.

The melody only makes sense

with this French-style ending,

for in the last line it takes

up the melody of the 2nd and

4th lines - linked to 11

syllables - while

the last line of the Provencal

text is connected with the 10

syllables of the 5th line. The

following pattern shows the

fundamental difference in the

forms of text and music:

Provencal / French

Rhymes / Melody

a / a

a / b

a / a

a / b

----------

b / c

a / d

b / b

We can see from this that the

form of the French melody does

not fit the text. It is

possible that the music

already existed before it

became linked up with the

text; and this at a time when

the latter was already being

interpreted in a French

manner.

All this shows that the link

between text and music was

looser than we are accustomed

to nowadays and that we do not

have to proceed from the idea

of a necessarily inseparable

union between the two.

As the texts were the decisive

criterion in the choice of

songs for this recording - all

texts are spoken partly or

completely by women - it was

found that only three of these

poems were handed down with a

melody (Nos. 4, 6, 7). The

melodies for the others were

all taken from Troubadour

songs with the same structure

of verse lines and stanzas; a

procedure very possible with

the above mentioned freedom

between text and music.

Usually, however, the poems of

the Troubadours show a very

individual form. Only in a few

cases existing poems were

imitated in form and rhyme.

Therefore it was not often

possible to take over a

melody. As an exception 18

more poems exist in the form

of the famous La grans

beutatz e·l fis

ensaenhamens by Arnaut

de Maruelh. His melody was

taken over for Na Carenza

al bel cors avinen (No.

3).

The Troubadour songs have been

handed down in notations which

restrict themselves to stating

the pitch and the grouping of

notes above the syllables;

length is not indicated.

Because of this ‘openness‘ in

the notation there are many

different opinions concerning

the rhythmical interpretation

of these melodies.

Fundamentally we can

distinguish two opposite ways

of reading: An older

interpretation subjects the

whole of the Troubadour

repertoire to the rules of

modal rhythmics, i.e. it uses,

according to the structure of

the verse, one of the patterns

of the modal theory of the

thirteenth century which is

repeated throughout the whole

poem. Against this theory it

can be pointed out that it

bases itself on the date of

the creation of the

manuscripts and that the time

interval as regards the origin

of most of the poems is not

taken into consideration. A

further and more important

argument is that the

rhythmical regularity of the

modes is in contrast to the

irregular groupings,

particularly of the melismatic

melodies. More modern

considerations stress the

distance of time, place and

social surroundings

between the theory of modes

and the ‘Lebensraum’ of the

Troubadours which makes such a

direct connection of the two

unlikely. During the last

years, therefore, the opinion

has become accepted that the

melodies should be performed

in a rhythmically free manner.

Either the recitation of the

text is made the determining

factor and the melody is made

subject to it, or the melody

derives its manner of

performance from its own

impulses - of course taking

into consideration that the

text must be understandable.

A modern interpreter has to

decide between these

possibilities. A decision for

a modal interpretation can in

some cases be justified, i.e.

where it seems to suggest

itself by a strong syllabic

connection between language

and music and by semi-tonal

melodics. The best way of

doing justice to this

situation is an openminded

approach to the question of

rhythmics in the Troubadour

melodies, giving the option of

a new decision for each

individual piece - rather than

a firm laying down of one of

the rhythmical theories.

The use of instruments for the

accompaniment of the songs is

even more dependent on the

decisions and the creativeness

of the performers. There are

no concrete pointers to the

way in which the instruments

were used and to what they

played. Neither do the

Provencal texts themselves

give any clues. Any attempt at

reconstructions is lost in the

vacuum of the tradition.

In modern performances the use

of a wide range of instruments

has become widely accepted,

the various instruments being

more or less similar to the

ones found in the miniatures

of medieval manuscripts. A

change of accent in the

performance is very

noticeable: The stress lies

not on the performance of the

text but rather on the musical

arrangement of a Troubadour

song. This is probably a

concession to modern audiences

who in most cases do not

understand the language and

who perhaps on the whole have

a different attitude to

language and poetry than the

audiences of the Middle Ages.

Thus every new confrontation

with the poetry of the

Troubadours is dependent on

present day conditions and is

shaped by the knowledge and

experience of each

interpreter, his musical

empathy, his weighing up of

questions concerning the

relationship of text and

music, rhythmics and

instrumentation. What makes

each performance fascinating

is therefore never its

historical authenticity;

rather the seriousness of its

confrontation with the

tradition, the quality of

performance and, last not

least, the musical directness

which is never or always

“historical”.

Karin

Paulsmeier

Translation:

P. H. Linnemann

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|