|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 939 Q - (p) 1977

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26484 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63145 2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| CANCIONES Y DANZAS DE ESPAÑA

- Lieder und Tänze der Cervantes-Zeit

(1547-1616) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I. ROMANCES Y

DANZAS DE MOROS Y MORAS |

|

|

| - La Perra mora

(Baile) (Pedro Guerrero, 16.

Jh.) |

1' 35" |

|

| - Romance de

Abinderráez: La Manaña de San Juan

(1552) (Diego Pisador, gest.

nach 1557) |

3' 59" |

|

| - Fantasia y

Gallarda (1546) (Alonso

Mudarra, ?-1580) |

3' 24" |

|

| - Romance del

Rey moro que perdió Alhama (1538)

(Luis de Narváez, 16. Jh.) |

3' 40" |

|

| -

Tres morillas m'enamoran (instr.)

(Anonym: Cancionero de Palacio) |

1' 35" |

|

| II. ROMANCES Y MADRIGALES

CORTESANOS |

|

|

| - Conde Claros

(Romance instr.) (1546)

(Alonso Mudarra, ?-1580) |

1' 57" |

|

| - Romance de Don

Beltrán: Los braços traygo

consados (1560) (Juan Vásquez,

gest. nach 1560) |

2' 34" |

|

| - Romance I:

Pues mon me quéréis (Anonym) |

1' 04" |

|

| - Romance II:

Mira, Nero de Tarpeya

(Francisco Palero, ?-?) |

1' 48" |

|

| - Dexó la venda

(Madrigal) (Francisco

Guerrero, 1527-1599) |

1' 51" |

|

|

|

|

| III. VILLANCICOS AMOROSOS |

|

|

| - Quien amores tiene (1560)

(Juan Vásquez, gest. nach 1560) |

1' 30" |

|

| - Dos ánades,

Madre (Juan de Anchieta, 16 Jh.) |

1' 26" |

|

| - Al rebueto da una garça

(instr.) (1557) (Anonym) |

1' 31" |

|

| - Pues

me tienes, Miguel (Ortega, 16 Jh.) |

2' 55" |

|

| - Madre,

la mi madre (1614) (Pedro Rimonte,

um 1600) |

3' 12" |

|

| IV. DANZAS Y BAILES PARA

CANTARY Y TAÑER |

|

|

| - Folia VIII (instr.)

(1553) (Diego Ortiz, um 1510-?) |

1' 47" |

|

| - La Gerigonza (Baile

cantado) (1554) (Mateo Flecha, gest.

1553) |

1' 24" |

|

| - El Villano (instr.)

(Antonio Martin y Coll, 17 Jh.) |

1' 54" |

|

| - Seguidillas en eco: De tu

vista celoso (Anonym: Cancionero de

Sablonara, um 1600) |

1' 55" |

|

| - Jácaras

(instr.) (Antonio de Santa Cruz, 17

Jh.) |

2' 39" |

|

| - Folia:

A la dulce risa del alva (Mateo

Romero, gest. 1647) |

2' 08" |

|

| - Danza

del hacha (instr.) (Antonio Martin y

Coll, 17 Jh.) |

1' 36" |

|

| - Chacona:

Ala vida bona (1624) (Juan Arañés.

?-?) |

1' 44" |

|

|

|

|

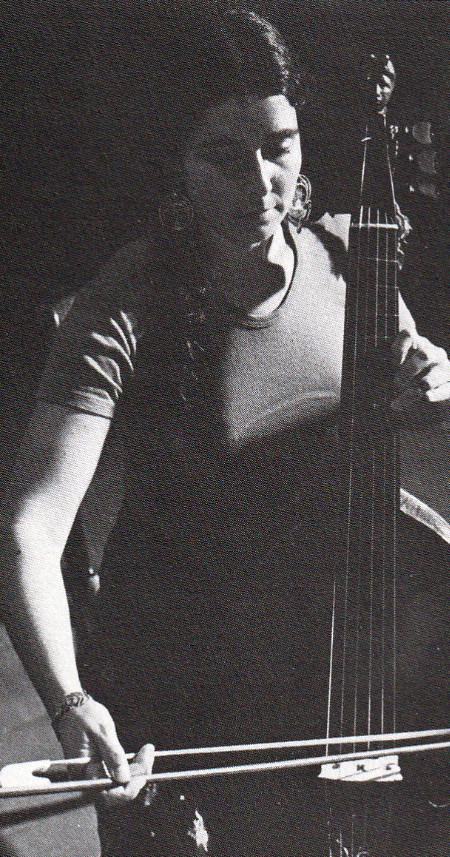

| ENSEMBLE

HESPÈRION XX / Jordi Savall, Leitung |

|

| -

Montserrat Figueras, Gesang |

|

| -

Jordi Savall, Renaissance-Diskant-

und Baßgamben |

|

| -

Hopkinson Smith, Viheula de mano

und Renaissancegitarre |

|

| -

Ariane Maurette, Renaissance-Tenorgambe |

|

| -

Christophe Coin, Renaissance-Baßgambe |

|

| -

Lorenzo Alpert, Renaissanceflöten

und Schlaginstrumente |

|

| -

Gabriel Garrido, Schlaginstrumente |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kirche,

Séon (Svizzera) - 10-16 settembre

1976 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

939 Q - (1 lp) - durata 49' 58" -

(p) 1977 - Analogico

(Quadraphonic) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63145 2 - (1

cd) - durata 49' 59" - (c) 1989 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26507 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 49' 58" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

The

epoch of the perhaps most

famous Spanish poet, Miguel de

Cervantes, creator of the

immortal Don Quixote,

marked the cultural and

political golden age of Spain.

It was the era of the severe

and austere Philipp II of

Hapsburg (1556-1598),

his religious wars in Europe

and his struggle against

heterodox people, especially

against the Turks. And in the

famous battle of Lepanto

(1571) which guaranteed Spain

the predominance in the

Mediterranean area again, the

poet and soldier Cervantes

lost his left hand. In this

epoch Spain replied to the

religious controversies with

the inquisition which

rigorously had to watch over

literature and faith. It was

the same period in which the

famous Spanish mystic

literature of Santa Teresa de

Jesus and San Juan de la Cruz

was written out of deep

religious belief. It was also

the epoch in which Spain

achieved her biggest

territorial extension and in

which the immense riches from

oversea colonies streamed into

the mother-country; but

nevertheless beside wasteful

luxury of a few and splendid

ornaments of cathedrals and

palaces greatest poverty was

to be found not only in the

lower classes of the

population, but also among the

representatives of the gentry

who gained a scanty living

because manual work was

inconsistent with their class

as we can clearly read it in

the picaresque novels of this

epoch. The

epoch of the perhaps most

famous Spanish poet, Miguel de

Cervantes, creator of the

immortal Don Quixote,

marked the cultural and

political golden age of Spain.

It was the era of the severe

and austere Philipp II of

Hapsburg (1556-1598),

his religious wars in Europe

and his struggle against

heterodox people, especially

against the Turks. And in the

famous battle of Lepanto

(1571) which guaranteed Spain

the predominance in the

Mediterranean area again, the

poet and soldier Cervantes

lost his left hand. In this

epoch Spain replied to the

religious controversies with

the inquisition which

rigorously had to watch over

literature and faith. It was

the same period in which the

famous Spanish mystic

literature of Santa Teresa de

Jesus and San Juan de la Cruz

was written out of deep

religious belief. It was also

the epoch in which Spain

achieved her biggest

territorial extension and in

which the immense riches from

oversea colonies streamed into

the mother-country; but

nevertheless beside wasteful

luxury of a few and splendid

ornaments of cathedrals and

palaces greatest poverty was

to be found not only in the

lower classes of the

population, but also among the

representatives of the gentry

who gained a scanty living

because manual work was

inconsistent with their class

as we can clearly read it in

the picaresque novels of this

epoch.

That was the official Spain of

Cervantes which is obviously

reflected in the construction

of the Escorial, the synthesis

of palace and cloister,

situated in the barren

highlands opposite Madrid,

which Philipp II had

founded and where he lived.

But this rather harsh picture

of Spain would be incomplete,

if we forgot the other,

cheerful and popular Spain

with her manners and customs,

dances and songs.

Cervantes once said, “There is

no Spanish woman who was not

born to be a dancer“. (Gran

Sultana, III)

And in the second book of Don

Quixote (II, 62)

the poet gives us a clear idea

of the passion for dancing of

the ladies at court. They

whirl round the knight until

he sits down in the middle of

the hall, exhausted and

heaving the memorable sigh, “Fugite,

partes adversae".

The most popular figure-dances

of the noble society were the

almaña

and the gallarda,

which were rather stepped than

danced, in strained grace to

the sound of the instruments

and the gentleman leading the

lady by gloves or a

handkerchief.

In the

popular art of dancing the

vivid baile

accompanied by castañuelas

- castanets - dominated and

displaced the solemn

figurative danza more

and more. Examples of purely

popular dances are the caponia

danced by a single person or

the rastreado

distinguished by a tearing

rhythm and vivid

gesticulations. The

contemporaries of this epoch

discussed a lot the dance

which was the latest craze -

the zarabanda whose

“devilish sound” after

Cervantes’s short novel El

Celoso Extremeño

was something new. According

to other reports it is said to

have been invented in 1588 by

an ill-reputed Sevillan lady.

The zarabanda mostly

accompanied by amorous and

satiric comic songs was in

this way used for marriages

and similar occasions. The

castanets beside guitar,

timbrel, tambourine or bagpipe

were the most important

accompanying instruments. For

the danza de cascabeles

little jingles were worn at

the ankle joint. Other dances,

e.g., the folìas

danced by travelling students

or the seguidillas and

seranillas were

accompanied by ditties called

by the same name. Beside these

dances countless names of

other forms of dancing are

transmitted and all have to be

considered as popular

spontaneous variations.

And not only secular

festivities were occasions for

dancing but also every church

festival. People even danced

in the church in front of the

altar. In

this way the festival gets its

festive and happy character. It is a

matter of course, for example,

that Cervantes’s Gitanilla

(little gipsy) in the short

novel of the same title,

dances a villancicos religioso

- a religious dancing song -

in front of the picture of

Holy Anne and castanets and

tingles are sounding to it.

And the countless processions

being held in honour of the

respective church-patrons on

canonizations and

beatifications, on

transportations of relics or

consecrations of monasteries

and churches, especially every

year on Corpus Christi Day,

were not rarely interrupted by

frantic dances, while mortars

and fanfares accompanied the

procession and liturgical

singing alternated with

instrumental music.

Beside these dances presented

by individual persons there

are the group dances shown by

guilds or also by professional

dancers. The silk weavers

danced the danza de los

palillos in which they

were carrying small rods

adorned with coloured ribbons

in their hands. In the danza

del cordon each of

sixteen dancers who had formed

a circle was holding a

coloured ribbon which was

fastened to a rod in the

centre decorated with flowers

held by a seventeenth dancer.

Furthermore there was the

dance of swords - danza de las

espadas - in which a

sham fight was carried out.

Fancy-dress dances were also

popular and so national events

such as the liberation from

the Moorish domination were

shown in choreographical

representations. Last not

least the allegorical dances

with their didactic amusing

character belong to the group

dances. Beyond all doubt the

Medieval Spanish art of

dancing and during the era of

the Habsburgs was influenced

by Arabic customs and

tradition, althought the

knowledge of this matter

leaves much to be desired. But

England’s Morisco dances show

how far Spanish - Moorish

forms of dancing have advanced

to the North.

The Spanish comedia - the

popular theatre of the golden

age - had effective inserted

dances, folk-dances were

mainly used. In the opinion of

some experts these folk-dances

are even the centre of

attraction regarding the

Spanish stage. The noisiness

and frenzy of these dances

were actually the main reason

for their being banned. But

their abolition by way of

trial, however, had nearly

resulted in the ruin of the

theatres. Finally the baile

also developed from dancing

parts of the comedia

into an independent dramatic

dancing play. It is a kind of

interlude with words

completely or partly sung. The

dance cannot be separated from

song and sound because

folk-music in this epoch is

nearly always either song or

dance accompaniment. The

guitar is the most popular

home and folk instrument and

the wealth of short-verse

lyric poetry are set to music.

Beside this, harp, mandolin,

timbrel and bagpipe are most

popular instruments. The

contemporary composers, who

were chapel singers or

choirleaders or even chamber

musicians at court, set to

music the lyric poetry by

famous and anonymous poets (Góngora,

Lope de Vega, Quevedo or

Figueroa e.g.) and in which

way romances, seguidillas,

novenas, sestines,

canciones and décimas

in short: the well-known comic

songs and love songs were sung

and played not only at court

but also in middle-class

families and in the streets

describes a valuable song

manuscript which a German

prince took from Spain into

his country. (The old song

manuscript, composed between

October 1624 and March 1625 by

Claudio de la Sablonara for

the Court Palatine and Duke

Wolfgang Wilhelm von Neuburg,

today in the Munich State

Library.)

The use of common dance-song

forms in the literature of the

epoch dating from the early

16th century shows us their

increasing popularity.

Cervantes in his short novel La

Ilustre Fregona gives us

a perfect example. Here a

classical sonnet is

accompanied by harp and

vihuela, a professional

musician sings a popular

romance (the Spanish form of

the ballade) and - a typical

expression of song - a

spontanuous form of dancing.

Dance, song and sound form a

unit in the popular as well as

in the court music of the

time, and if they are

separated, it would be

impossible to understand them

adequately.

Ursula

Vences

In the

world hardly explored of the

Spanish music of the 16th

and 17th centuries, the

extraordinary contribution

which gives us Miguel de

Cervantes is an unexhaustible

source of references to the

musical taste and life of the

Spanish people. It is not only

in Don Quixote, but

also in the major part of his

work that music constitutes an

essential component (El

Celoso Extremeño,

La Gitanilla, La ilustre

Fregona), whether as an

additional element or with the

intention of intensifiying the

action (El Quijote, El

rufiáno

viudo, Persiles y

Segismunda), or as an

independant element of the

action with a view to linking

the different scenes (above

all in the comedias

and interludes).

Cervantes takes music as a for

the most part ennobling

element; Many of his

characters are musicians or in

some way concerned with music.

Let us quote the famous

sentence Sancho Panza

addresses to the duchess: “Madam,

where you hear music, there

cannot be any evil.” (2nd

part, chap. XXXIV). Or Don

Quixote’s remark: “I want

you to know, Sancho, that all

or nearly all knight-errants

of bygone days were great

poets and great musicians.”

(1st part, chap. XXIII).

Or Altisidora: “We will have

to put down the lute for Don

Quixote undoubtedly wants to

make a music that cannot be

bad since it comes from him.”

(2nd part, chap. XLVI). So

it becomes evident that also

Don Quixote was a musician and

perhaps he had also had a

talent for extemporizing.

As to the diversity of

Cervante's style we must also

emphasize the musicality of

his vocabulary, above all as

far as important things are

concerned. So, for example,

Don Quixote calls his horse by

the name of Rocinante,

“in his opinion a majestic and

melodious name", and his lady

is called Dulcinea del

Toboso, “to his mind a

musical and miraculous name".

In all

his works Cervantes gives us

proof of his profound musical

knowledge and, above all, his

sympathetic musical

understanding which comes to

the fore in the fascination

the human voice exerts upon

him; we often find that it

sounds like a “bewitching

chant", there is often “a

voice singing in such a

wonderful and lovely harmony

that it fills you with

amazement and makes you listen

till the end.” The best

example is the character he

created towards the end of his

life: the singer Feliciana

de la

Voz, so called because

she had "the

best voice in the world" and

astonished all her listeners

when letting her voice take

its course and singing.” Persiles

y Segismunda (Vol. III,

chap. IV

and VI).

Most

interesting are also the

descriptions Cervantes gives

of the musical instruments and

their combinations. These are

the stringed and keyboard

Instruments he mentions; rabel,

guitar, vihuela,

lute,

harpsichord, psaltery,

organ; wind

instruments: flute, pifano,

shawns (chirimia,

albogue, dulzaina,

churumbela), whistle,

Pan pipe, gaita

zamorana, trumpet,

hunting-horns, trombone,

bugle, trompeta

bastarda, horns

(cuerno, bocina,

trompa de Paris);

percussion instruments: tambourine,

drummer, pandero,

jingle,

tamboril, castanets,

cow-bells, ratchets

etc..

The musical works mentioned by

Cervantes give also a great

deal of information about the

musical taste of his time.

As to the numerous romances he

mentions, the romances del Conde

Claros de Montalbán,

Don Beltran concerning

the famous battle of

Roncesvalles and the Morisco

romance Abindarráez

y Jerifa are included in

this recording. Romances of

the latter type were very popular

and, for this reason,

suppressed (so for example the

romance of the Morisco

king who lost

Alhama), to prevent the

Morisco

people from revolting.

As to the villancicos

and songs Cervantes mentions,

Madre, la

mia madre and Tres ánades,

madre are sung here.

As to the folk- and

court-dances, Cervantes gives

us a good description of those

which were in fashion at the

time, so, for example, folía,

canarie, chacona,

gallarda, jácara,

moresca, seguidilla,

villano, zarabanda,

and perra mora. Perra

mora is the name of a

dance which had adopted the

first words of its orginal

text for all following

variations. A variety of the villano

(literally ‘country dance’)

was also cultivated at court,

as we may conclude from

Cervantes’s works. The folía

(literally ‘mad, wild dance’)

as well as the zarabanda,

seguidilla, and chacona

had been very wild dances at

his time, but grew to be

rather slow and moderate in

the course of the 17th century

when becoming popular almost

throughout Europe, with the

exception of the seguidilla

which was soon quite

forgotten.

Trying to give a general view

of the fascinating diversity

of the secular music during

the time of Cervantes we have

chosen pieces of great

importance for this writer`s

work, not only by reason of

their musical quality and

historical import, but also

because of their evocative

power and representative

character. Concerning the

performance of these pieces,

we have also made allowance

for the different historical,

technical and stylistic

elements typical of this

period, a difficult task since

this is a music which was

cultivated more than three

centuries ago.

These are fundamental

questions with regard to the

fact that these romances,

songs and dances are the

expression of the soul of a

people of bygone days, but as

such a lasting expression

which we today should be able

to experience and to

understand - not as a

historical event, but as a

reflexion and cristallization

of a music having no like or

equal.

Jordi

Savall

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|