|

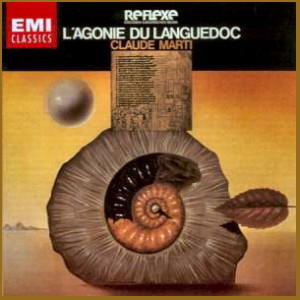

1 LP -

1C 063-30 132 - (p) 1976

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26500 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| L'AGONIE

DU LANGUEDOC |

|

|

|

|

|

| - Tartarassa ni

voutor (Péire Cardenal,

1180?-1278?) - Sängerin, Laute,

Sänger, Instrumentalensemble und

Rezitation |

7' 11" |

|

| - Ben volgra

(Péire Cardenal, 1180?-1278?) - Sänger

(Altus), Fidel,

Instrumentalensemble und

Rezitation |

8' 05" |

|

| -

Razos es qu'ien m'esbaudei

(Péire Cardenal, 1180?-1278?) - Sänger

und Instrumentalensemble |

12' 42" |

|

|

|

|

| - D'un sirventes

far (Guilhelm Figueira) - Chanteur

und Gitarre |

2' 33" |

|

| - Si col flacs

molins torneja (Tomier et

Palazi) - Chanteur und 2

Gitarren |

7' 09" |

|

| - L'afar del

comte Guió (Péire Cardenal,

1180?-1278?) - Sänger und

Instrumentalensemble |

8' 44" |

|

| -

Ab marrimen (Péire Bremon Ricas

Novas) - Chanteur und 2 Gitarren |

5' 26" |

|

| -

Ab greu cossire (Bernart

Sicart Marjevols) - Rezitation

und Laute |

3' 48" |

|

|

|

|

| STUDIO DER FRÜHEN

MUSIK |

|

-

Andrea von Ramm, Sängerin und

Organetto

|

|

-

Richard Levitt, Sänger und

Schlaginstrumente

|

|

| -

Sterling Jones, Streichinstrumente |

|

| -

Thomas Binkley, Zupfinstrumente |

|

mit

|

|

| -

Claude Marti, Chanteur und

Rezitation |

|

| -

Benjamin Bagby, Sänger |

|

| -

Harlan Hokin, Sänger |

|

| -

Alice Robbins, Streichinstrumente |

|

| -

Paul O'Dette, Zupfinstrumente |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Münstermuseum,

Basel (Svizzera) - 28 giugno / 1

luglio 1975 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

132 - (1 lp) - durata 56' 11" -

(p) 1976 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26500 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 56' 11" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

This recording

offers something very new in

Early Music recordings: the

combination of 13th century

troubadour in its original

ambiente, and modern chanteur

in the Langue d'Oc of

today. The revitalization of

this ancient language today

makes this unusual combination

possible; the texts are all

original 13th century poems,

yet when Claude Marti is

singing these texts he is

thinking of today’s Languedoc,

striving once again after

seven centuries, for its

deserved cultural

independence, which was lost

in this Albigentian Crusade.

We hope that this unusual

combination of musical genres

will offend the devotees of

neither field, but rather will

direct the attention to the

continuity of this forgotten

culture.

----------

The Early

Music Quartet revives here

songs concerned with a

devastating French invasion of

Languedoc, which began in 1209

and which systematically

destroyed in the cruelest

manner the towns, chateaux and

monasteries of the South,

thereby breaking apart the old

and established social

structure which had provided

Europe with its most advanced

civilization after that of the

Spanish Arabs. As Ibn Khaldûn

(14th century) wrote in “The

Muqaddimah": “A nation that

has been defeated and has come

under the rule of another

nation will quickly perish."

So it was with Languedoc,

today a forgotten country of

the Middle Ages.

This was the homeland of the

troubadours, the cradle of

culture in Europe, whose

literature remains a

cornerstone of Western lyric.

Troubadour is the French word,

French the conquerors’

language. In

Occitanian the word is

trobador. This language, which

is a mixture of several Latin

dialects and might as well be

called Old-Provençal,

Occitan or Langue

d’Oc was an outgrowth of

the vernacular Latin as spoken

in the “Gallia Narbonensis”

and in “Aquitania", with the

Atlantic on the west, Italy on

the east, the Central Massif

on the north and the

Mediterranian on the south:

Gascogne, Limousin, Languedoc,

Auvergne, Perigord and Velay

are the areas where the

language is spoken. At the

time of trobadores the

language was one with

Catalonian, and even today the

regional dialects clearly

belong together, one language,

not French and not Castilian.

It was

the language of Frédéric

Mistral who won a Nobel prize

for literature in 1904, and it

is the language of a large

group of poet-singers today,

the “Chanteurs Occitans”, who

cultivate the chanson with

political overtones in their

own language; a group of

modern trobadores who are

carefully watched by a

government fearful of their

separatist tendencies.

Claude Marti is one of these

chanteurs, certainly the

best-known. During the day he

teaches in a village school

and during the summer season

he sings nightly in concerts

throughout the South. He is

not a worldly man, and when he

sings about minorities that

have been forbidden cultural

rights (L’Express

observed recently that Japan

has two university chairs for

Occitanian and on for Provençal

while France has none!) he

is simply singing about

himself and his own Occitanian

minority.

The Early Music Quartet and

Marti join hands on this

recording. His living

language, his identification

with the same cause as his

ancestors blend with the

revival of the historical

music and give life and

immediacy to the collection of

songs. The Early Music Quartet

brings original trobador songs

while Marti takes original

trobador texts and sings them

in his own musical style. No

music has survived for the

texts that Marti sings here,

and although seven centuries

lie between the original music

of the trobadors and today,

the power of the language

convincingly bridges this

hiatus. For it is not the

musical style, it is the

anger, despair and

helplessness at the ravaging

of the Languedoc, the

frustration of a people

subjected to a cultural

starvation economy that unites

the pieces on this recording;

magnificent poetry which has

outlived that forgotten war,

the Albigentian Crusade.

This recording is not a song

recital; it is an attempt to

portray the art and the

feelings of a civilization

about to die.

Thomas

Binkley

THE ALBIGENTIAN CRUSADE

“KilI them all, God will

recognize his own!”

There in Béziers, 22 July 1209

the crusading army murdered

the entire population of the

town, Christians and Cathars

alike, took what there was to

take and burned what would

burn. The first action

(campaign) of the army of

Abbot Arnaud-Amaury de Citeaux

was complete!

The events leading up to this

slaughter are not complicated,

they are simply ordinary

political history. At the

Council of Toulouse in 1199

the Cathars, a harmless,

aescetic Paulician sect was

declared heretical. In 1204

the new Pope, Innocent III

decided upon active

persecution of the heretics.

Count Raimond VI of

Toulouse (Languedoc) was not

active in supressing them, and

the Papel Legate, Pierre de

Castelnau was successful in

bringing about a Papel ban on

the Languedoc. On 15 January

1208 Pierre de Castelnau was

murdered, a crime unsolved to

this day.

Innocent III

then called for a crusade

against Languedoc - how else

might he exercise his power if

his bann be ignored and his

legate killed? Thus the highly

cultivated, most civilized

part of Europe was offered to

the Northern brigands for the

taking on the scanty

justification that Raimond

VI was insufficiently zealous

in persecuting a small

minority within his lands. The

Abbot Arnaud-Amaury in Lyon

began to organize an army

which led to the disasterous

rape of Provence and the

Languedoc, which began the

following year with the razing

of Béziers.

After Béziers

the crusaders, who included

the most powerful barons of

the North, moved on to

Carcassonne, where the

citizens were permitted to

leave the city alive but

naked, and all their

belongings became the property

of the French crusaders. But

these were the lands of the

Viscount Raimond-Roger

Trencavel, and the counts of

the North felt uncomfortable

about taking them over from

the hand of an abbot. Indeed,

can the church take the lands

from one count and give it to

another? Burgundy and Nevers

and Saint-Pol thought not, and

decided to leave the crusade.

Only one was found who in

pious humility would accept

the poisoned gift from Rome of

such magnificent wealth -

Simon, Count of Leicester und

Montfort.

Simon thus became the leader

of the crusade, and he

supplemented his army after

the departure of his more

powerful colleagues with

mercenaries from many places.

Simon turned to the chateau of

Bram. There he sent the

defenders off in a long chain

of human misery, blinded and

with their noses out off, with

a oneeyed man to lead them,

off they went to Cabaret. In

the wake of such cruelty, who

would dare to defend his

house, who would fail to open

his gates to welcome the

cleansing crusaders? Minerve:

there he burned 140; Termes,

Cabaret, Lavaur, where he

burned between three and four

hundred, Cassés

and Castelnaudry, only sixty,

and then a grand massacre at

Moissac, and then Muret... on

and on: Pierre de Vaux-Cemai:

“Innumerabile

etiam haereticas peregrini

nostri cum ingenti gaudio

combusserunt”. (Historia

Albigensium, cap. LII).

In the

Statutes of Pamier

Simon set forth the

organization of his

conquests... what did it

matter to him that much of the

land belonged to the English

crown, some to Philippe

Augustus and 'some to Peter of

Aragon. What did the law

matter to him? He was master

there now, hated and reviled

and feared. Soon his army was

to stage a sensational victory

over Peter II

of Aragon, who had returned

from his own sensational

victory over the Moors at Las

Navas to aid Fiaimond VI of

Toulouse. But Simon’s politics

cf terror and cruelty were

repaid during the long siege

of Toulouse in 1217 by a stone

which crushed his head. “Simon

est mort, Simon est mort!"

Simon de Montfort was dead,

but it was too late to turn

back what he had done.

Languedoc, weakened by ten

years of tragic war, the

cultivated house torn asunder,

was never to regain its

splendor. The war went on,

lands fell to the French and

here and there heretics were

burned, monasteries plundered

and people put in fear of life

and property. One of the last

stands, Montségur fell

heroically as late as 1244,

and the châteaux

of Quéribus

and Puylaurens survived for

another ten years. All the

while the Inquisition

worked to intimidate all,

especially the poets: The

Abbot of Villemeir addressed

the poets with a poem of his

own, containing the refrain:

E

s’aquest no vols croyre vec

te'l foc

aizinat que art tos

companhos

Aras

velh que m respondas en un

moto en dos

si

cauziras el foc o remanras

ab nos.

If you

don't wish to believe this,

then look

into the fire

where your

companions are burning

and give me

your response in one or two

words,

whether you

want the fire too or will join

us.

In the end it was Raimond VII of

Toulouse who alone did not

accept the new order. One by

one the others, Olivier de

Termes, the Count of Fois, Raimond

Trencavel of Carcassonne and

Béziers, and the rest, all

were sufficiently intimidated

to accept French rule, and so

it has remained to this day. Raimond

VII died 1249 powerless and

defeated, nor was his lineage

to be sustained.

Thomas

Binkley

LANGUEDOC

The history and culture of

Languedoc had little in common

with that of France. Its

civilization was a peculiar

mixture of Roman,

Visigoth and Moslem,

it had no clearly definable

geographical boundaries beyond

the sea und the Pyrenees. The

Visigoth Septimania, called so

after the seventh Roman

legion, comprising the land

round the cities of Narbone,

Carcassonne, Elne, Béziers,

Maguelonne, Lodève and

Agde, corresponds roughly to

the land that became known as

Languedoc. Following its

separation from Aquitaine in

817 it became a duchy. By the

opening ofthe 13th century the

authority of the house of

Toulouse was recognized

throughout half of Provence,

at that time the wealthiest

and most highly cultured area

of what today is France.

But with the French invasion

of 1209 the sun went down on

the Languedoc and the dark

ages descended. By the treaty

of 1229 all the lands from

Carcassonne to the Rhone went

to the French, and after the

death of the last of the

Toulouse line, Jeanne, in 1271

the rest of the Languedoc went

to the French Crown. (In 1274

Rome

illegaly took the county of

Venaissin, laying the basis

for the Papal residence in

Avignon during the Captivity.)

Improper

rule and heavy taxation led the

infuriated peasantry to

rebellion 1382-83, which was

harshly and cruelly put down.

(Both Louis of Anjou, brother

of Charles V, and the Duc de

Berry can be blamed for much

of this misery.)

In 1790

Languedoc was simply erased

from the map of France, being

replaced by the several

departements.

Thomas

Binkley

THE

TRUBADORES

Pèire Cardenal was the

arch-Satirizer of the

period. He was born in

Puy-en-Velay and served as a

secretary to Raimond

VI of Toulouse beginning

1204. Thus he was a young

man at the outbreak of the

war. He enjoyed a clerical

education but chose to

become a trobador. He lived

through the war and the

death of the members of the

House of Toulouse, Raimond

VI, Raimond

VII and his daughter (died

1271). Cardenal was not a

Cathar, remaining within the

church all his life, yet he

was outspoken against the

French and the church. Very

likely it was the

Inquisition that compelled

him to go into exile - he

selected Montpellier, which

at that time was a fief of

the king of Aragon.

Cardenals satire was bitter

in the extreme. His audience

was educated and he himself

frequently cited figures out

of the literature -

Blancheflor, Isolde, the Isengrim

fables, etcetera. As was the

custom, he modelled his

sirventes after canzones,

employing borrowed melodies,

which gave him a subtile

satirical tool: view the

beautiful soave melody of Tartarassa

and then regard the text!

Guilhem Augier Novella was

born in Saint-Donat

(Valence) in 1185 and became

a minstrel at the court of

Raimond Rogiers in Béziers.

Following the execution of

Raimond (10 November 1209 at

the hands of the French)

Guilhem went into exile in

Italy, where he received the

name “Novella”.

Pèire Bremond Ricas Novas

was a Provençal

trobador who worked from

1229 to after 1241. He

worked at the court of

Raimond VII in Toulouse.

Tomier and Palazi were two

trobadores who wrote

sirventes on James I of

Aragon (1208-1276),

the Count of Provence,

Raimond-Bérenguèir

IV (died 1245) the Count of

Toulouse, Raimond

VI (died 1222).

Guilhem Figuèira

was from Toulouse, son of a

tailor, and he was one

himself. When the French

occupied Toulouse (1229) he

fled to Lombardy. He could

write well and sing well,

but, the vida tells us, he

kept the company of whores

and ribalds in the taverns

rather than that of the

courtiers. The vida omits

mention of his most famous

poem, Sirventes farai

(record side 2). Such a

devastating attack on the

church may have prompted the

writer of the vida to

discredit him before history

with the remark about his

character: mere possession

of a copy of this poem was

succicient grounds in the

fourteenth century in

Toulouse, to come before the

Inquisition!

Thomas

Binkley

GUILHEM DE TUDELA

Cançon

de la Crosada

The text usually

entitled Chanson de la

croisade albigeoise

(Song of the Albigentian

crusade) - the original has

no title, and the note Aiço

es la cançons

de la crosada contra’ls erètges

d'Albigès

was given to it by Fauriel

in his edition of 1838 - is

composed of two quite

different, but successive

works. The first part (2,772

lines) was written in a bad

frenchified Occitan dialect

by a Spaniard from Navarre

whose native language must

have been Basque: Guilhem de

Tudèla.

He was a priest who favoured

the crusade, but not a

fanatic and wrote his poem,

which is almost nothing but

a document, in the course of

the events between 1210 and

1213.

The first extract given here

tells the origins of the

crusade, the second alludes

to the taking of Lavaur (May

3, 1211), when the lady of

the castle, Girauda, was

thrown in a well and stoned

to death, when the knights

were hanged or beheaded and

the heretics burnt at the

greatest stake of the

crusade.

Thomas

Binkley

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|