|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 129 - (p) 1976

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26497 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

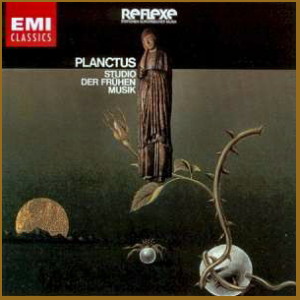

| PLANCTUS |

|

|

|

|

|

| Planctus cigne |

|

|

| - Clangam, filii

(Anonym) - Text nach Bruno

Stäblein |

6' 31" |

|

| 4 Planctus from

las Huelgas |

|

|

| - Plange Castilla

(Sancho III) - Text nach Higini

Angles |

3' 45" |

|

| -

Quis dabit (Fernando III?) - Text

nach Higini Angles |

5' 02" |

|

| -

Rex obiit (Alfonso VIII) - Text

nach Higini Angles |

4' 07" |

|

| -

O monialis concio (Fernández de

Agüero) - Text nach Higini

Angles |

6' 07" |

|

|

|

|

| - Ples de tristor

(Guiraut Riquier, um 1150-um 1220) |

12' 33" |

|

| - Fortz chausa es

que tot lo major dan (Gaucelm

Faidit, um 1230-um 1300) |

8' 19" |

|

| - Tristor et cuncti

tristantur (aus der Bordesholmer

Marienklage, um 1476) (Anonym)

- Text nach Friedrich

Gennrich |

4' 24" |

|

|

|

|

| STUDIO DER FRÜHEN

MUSIK / Thomas Binkley, Musikalische

Enrichrung |

|

| -

Andrea von Ramm, Sängerin |

|

| -

Richard Levitt, Sänger |

|

| -

Sterling Jones, Rabel morisco,

Lira und Vielle |

|

| -

Thomas Binkley, Laute und

Chitarra saracenica |

|

| unter

Mitwirkung von |

|

| -

Benjamin Bagby, Sänger |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Evangelische

Kirche, Séon (Svizzera) - 24

maggio / 2 giugno 1976

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

129 - (1 lp) - durata 50' 59" -

(p) 1976 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26497 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 50' 59" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Planctus means

lament, the expression of

grief and sorrow, regret or

sadness. Planctus, in medieval

times was this expression in

song. The origin and history

of planctus is long and

intertwined with the history

of the lai and the sequence,

Some planctus, such as those

of Peter Abelard (cf 1C 063-30

123) are written on Biblical

themes and are of great

length. The use of the Latin

language separates them from

the vernacular lai. They are

called planctus because the

text presents a tragic

situation. A planctus may be

an allegory (Planctus

Cigne in the present

recording) in which calamity

is inferred. Many planctus are

more personal than these,

being monuments on the death

of real people, usually people

in the political arena. These

planctus, being of a later

date, may be in the vernacular

and may employ ordinary song

structures (Ples de tristor,

Fortz chausa in the

present recording). The

structural difference between

these types is clearly seen in

a comparison of Planctus Cigne

with the later vernacular

planctus. Planctus Cigne

employs the principal of the

lai, in which sections of

differing length (puncta)

are sung one or more times,

always with new text, never to

recur having once been

dropped. Ples

de tristor, onthe other

hand, is a strophic song

concluding with a tornada, a

repeat of the last portion of

the melody. The Latin planctus

from Las Huelgas may be viewed

as strophlc songs with but a

single strophe. Planctus means

lament, the expression of

grief and sorrow, regret or

sadness. Planctus, in medieval

times was this expression in

song. The origin and history

of planctus is long and

intertwined with the history

of the lai and the sequence,

Some planctus, such as those

of Peter Abelard (cf 1C 063-30

123) are written on Biblical

themes and are of great

length. The use of the Latin

language separates them from

the vernacular lai. They are

called planctus because the

text presents a tragic

situation. A planctus may be

an allegory (Planctus

Cigne in the present

recording) in which calamity

is inferred. Many planctus are

more personal than these,

being monuments on the death

of real people, usually people

in the political arena. These

planctus, being of a later

date, may be in the vernacular

and may employ ordinary song

structures (Ples de tristor,

Fortz chausa in the

present recording). The

structural difference between

these types is clearly seen in

a comparison of Planctus Cigne

with the later vernacular

planctus. Planctus Cigne

employs the principal of the

lai, in which sections of

differing length (puncta)

are sung one or more times,

always with new text, never to

recur having once been

dropped. Ples

de tristor, onthe other

hand, is a strophic song

concluding with a tornada, a

repeat of the last portion of

the melody. The Latin planctus

from Las Huelgas may be viewed

as strophlc songs with but a

single strophe.

Planctus Cigne

Planctus

Cigne (the Swan’s

Lament), is perhaps the most

famous of all

planctus, known to modern

listeners through the Carl

Orff Carmina Burana

score. Indeed the original

version is quite different!

This is one of six Carolingian

sequences which have survived

in about two dozen manuscripts

from the 9th to 13th

centuries. Planctus

Cigne underwent many

changes in the course of time,

and new texts were added to

provide a religious

significance to the allegory.

The original text contains the

following story: a swan flies

out from land over the sea,

and encounters a storm. The

swan laments its fate as it is

tossed about in the waves, too

weak to rise above the storm

and unable to catch the many

fish which would give

sustenance. But as morning

breaks, the storm subsides and

the swan regains its strength,

and it is able to fly joyously

back to the land.

Four Planctus from Las

Huelgas

Las Huelgas is the name of a morastery

near Burgos in Old Castile. It was

founded by

Alfonso VIII,

who gained fame especially for

his victory over the Moslems

at the battle of Las Navas de

Tolosa in 1212. Some time

after his death a planctus was

written in his honour, Rex

obiit, which was

assimilated into this large

manuscript. It

was another scribe that

entered Plange Castilla,

a lament on the death of

Alfonso’s father, Sancho III, on

whose death the kingdoms of

Castile and León were

divided between two sons. (It is

interesting to note that the

Spanish kings were connected

to the dominant European

cultural developments: Alfonso

VIII,

for example was married to

Eleanor, daughter of Henry II

(Anjou) of England and Eleanor

of Acquitain, a symbol of the

troubadour culture; Richard

Coeur de Lion was a son of

that union, whose death was

the subject of another

planctus discussed below).

Another Las Huelgas planctus

is Quis dabit capiti meo

aquam, possibly written

onthe death of the grandson of

Alfonso VIII,

Ferdinand, later Saint

Ferdinand (San Fernando). The

final planctus laments the

death of the Abbes of Las

Huelgas, and contains the

inscription De dompna Maria

Gundissalvi de Aguero,

abtissa

et nobilissima

super omnes abbatissas.

This Maria

Gonzàles

was a member of a renowned

family, one of whose members,

Pero Gonzáles

de Aguero was present at the

ceremony prepared by our

Abbess at Las Huelgas two days

before the coronation of the

young Alfonso XI, and

who continued in the service

of Peter “the cruel", son of

Alfonso XI.

Ples

de tristor

(Guiraut Riquier)

Guiraut was born about 1230,

in Narbonne, at that time a

town of business rather than

courtly affairs. His

first song is dated 1254 and

seems to be addressed to the

wife of the Vicecount of

Narbonne. Later, unable to

secure a worthy existence in

the Languedoc after the

ravages of the Albigentian

Crusade (cf. 1C 063-30

132), Riquier went to Spain,

at the court of Alfonso X el

Sabio in Burgos. Here he

remained some ten years,

active as a poet-composer.

Guiraut wrote an epistle 1274

to Alfonso in which he bade

the king to decide upon a

vocabulary for the different

sorts of artists - Guiraut

suggested there be four

categories beginning with the

acrobats and tight-rope

walkers, for which he

suggested the term jongleurs,

while menestrels

would include the musicians

and singers, trobadores

the authors and composers,

while doctores de

trobar would include the

recognized masters (to which

class he certainly ascribed

himself). About 1279 Riquier

left Spain for the protection

of Count Henry II of Rodez,

who still was able to continue

something of the

pre-Albigentian life style.

Guiraut wrote a song book

containing his own

compositions arranged in

chronological order. Two

copies of this book have

survived, one clearly copied

from the original, for it

contains the following

heading: Aissi comensan los

cans d'En Guiraut Riquier

de Narbona,

en aissi cum es de cansos e

de verses e de pastorellas

e de retroenchas e de

descortz e d'albas e

d’autras diversas obras, en

aissi adordenadamens cum era

ordenat en lo sieu libre;

del qual libre escrig

per la

sua man fob aissi tot

transladat; e ditz on aissi

cum de sus se conten.

Unfortunately, the complete

copy (Paris f. fr. 856)

contains no music, however the

shortened copy does contain 48

melodies, among them our

planctus. This planctus bears

the inscription: Planh que

fe Gr. Riquier del senher de

narbona

l'an MCCLXX e es uers

plahn. - written in

other words 1270 on the

death of Amalric IV, Vicecount of

Narbonne.

Fortz

chausa es que tot lo major

dan

(Gaucelm Faidit)

Somewhat younger than Guiraut

Riquier

was Gaucelm Faidit, born in

Uzerche not far from

Ventadorn, the home of Bernart

de Ventadorn (cf. 1C 063-30 118);

in fact, Gaucelm was enamoured

of Maria

de Ventadorn discussed in the

razos. He

was a conservative poet, the

vida says he had a very bad

voice and the Monk of Montaudon

tells us how small his sphere

of influence was - so it is

somewhat surprising that he

should be the author of the

most famous troubadour

planctus, this on the death of

Richard the Lion-hearted.

Richard died, it will be

recalled, 1199 during a minor

struggle with one of his

vassals; Richard’s

insignificant death did not

distract from his significant

life: it was Richard who was a

match for Saladin inthe Outre

Mer,

and his accomplishments there

towards restoring Western

influence were greater than

any other leader, including

his enemy Philip Augustus. It

had been the news in 1187 of

the fall of Jerusalem that

sent him off along with

Frederick Barbarossa and

Philip, and it was in 1190

that he set off, one year

after his coronation as the

English king (for

Faidit he was certainly better

known as the Duke of

Aquitaine).

Tristor et cuncti

tristantur

Tristor et cuncti

tristantur is an excerpt

from the so-called Bordesholm

Lament, which was regularly

performed at the cloister of

Bordesholm (near Kiel in

northern Germany) on Good

Friday or on Monday of Holy

Week. It lasted 2-1/2 hours.

Several of the sections of

this work -

which resembles a Passion or

Passion Play, employ melodies

known to the secular sphere:

the one selected here is that

melody employed by Walther von

der Vogelweide

for his Palaestina song, Nu

aler erst..., a melody

that Walther adopted from the

troubadour song ot Jaufre Rudel,

Lanquan li

jorn.

Concerning the

Interpretation:

More

and more it is the tendency in

the performance of medieval

music to rely somewhat on

instinct where the facts run

out. This ought not to be a

license for unsubstantiated

music-making (although I feel

it often is), but ought be

viewed as a necessary

challenge. One unfortunate

result of this however, is

that it is difficult in the

extreme to keep the listener

informed of the substance of

the musical position, with the

result that much is

misunderstood. What may seem

to the listener a minor sixth

chord may be in reality the

result of the drone strings on

that particular instrument,

and what may seem rambling

improvisation may really be a

detailed expansion of tones

according to a clear

discipline.

So I feel it might be of

interest to the listener to

have pointed out here that the

opening of the Planctus Cigni

is a Lydian scale (transposed)

encompassing the tones of the

melody to come, and followed

by suggestions of subjects

such as a descending fourth as

a swan symbol (from the melody

at the word cigni),

that the accompaniment derives

from musical symbols contained

in the melody, such as the

weaving through three or four

notes in the lament beginning

with line 5, leading to the

resolution at dulcimodo

cantitans and the swan’s

return to land.

Such an approach is not

employed in the four planctus

from Las Huelgas, where

symbolism takes a back seat to

basic musical materials of

mode and imitation, drone and

structure.

Still another approach is

employed in the naive

Bordesholmer planctus, where

it is the tuning of the

instrument, drones plus a

single melody string, that

dictates the tone

combinations.

And

finally the two troubadour

songs are treated as I would

any straight-forward

troubadour songs, connecting

the character of the

instrument with the expression

of the text, by drawing

attention to specific tones

and intervals that I feel are

of particular importance in

the song.

The

instruments employed include

two sorts of medieval lute,

lira, vielle, chitarra

saracenica, rabel, morisco.

Thomas

Binkley

Sources:

- Kiel, Univ.

Bibl. Mscr. 53 4° (Bordesholmer

Marienklage)

- Las Huelgas,

Codex musical (facs. ed. H.

angles)

-

Milano, Bibl. Ambrosiana R

71 sup. (Manuscript G, ed.

Sessini)

-

Paris, B. N. lat. 887

(Limoges, St. Martin)

- Paris,

B. N. n. a. lat. 1084

(Limoges, St. Martin)

-

Paris, B. N. f. fr.

22543

(Manuscript R)

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|