|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 128 Q - (p) 1976

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26496 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

1 CD -

CDM 7 63437 2 - (c) 1991

|

|

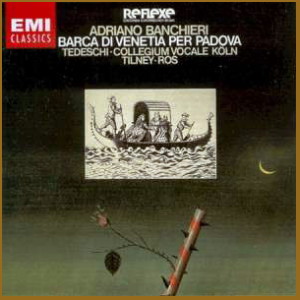

| ADRIANO

BANCHIERI (1567-1634) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Barca di

Venetia per Padova -

Dilettevoli Madrigali à cinque

voci |

|

|

|

|

|

| Introduttione |

|

|

| - L'Umor Svegliato |

1' 49" |

|

| - Strepito di

pescatori |

1' 57" |

|

| Partenza |

|

|

| - Parone di barca e

Ninetta |

2' 41" |

|

| - Barcaruolo à

Passagieri |

1' 20" |

|

| - Libraio Fiorentino |

1' 09" |

|

| - Maestro di Musica

Luchese |

1' 20" |

|

| - Concerto di cinque

cantori (Cinque cantori in diversi

lenguaggi) |

2' 40" |

|

| - Venetiano e

Thedesco |

1' 44" |

|

| Madrigale |

|

|

| - Madrigale

affettuoso |

3' 02" |

|

| - Madrigale

capriccioso |

3' 51" |

|

| - Madrigale in

dialogo |

1' 29" |

|

|

|

|

| - Dialogo |

2' 27" |

|

| Aplauso |

|

|

| - Mercante bresciano

et Hebrei |

1' 50" |

|

Madrigale

|

|

|

| - Stile del Marenzio

Romano (Madrigale alla Romana) |

2' 55" |

|

| - Madrigale à

imitazione del Spano Napolitano

(Madrigale alla Napolitana) |

2' 26" |

|

| - Prima Ottava

all'improvviso nel Liuto (Ottava

rima all'improvviso nel Liuto) |

1' 56" |

|

| - Seconda Ottava

all'improvviso nel Liuto |

2' 01" |

|

| - Aria à imitazione

del Radesca alla Piemontese nel

Liuto (Aria à imitazione del Radesca

nel liuto) |

2' 03" |

|

| - Barcaruoli

Procaccio e Tutti al fine

(Barcaruoli Procaccio e tutta la

Camerata) |

2' 07" |

|

| - Soldato

svaligiato |

2' 41" |

|

|

|

|

| Gianrico Tedeschi,

Sprecher |

|

|

|

| COLLEGIUM VOCALE

KÖLN |

|

| -

Michaela Krämer, Sopran |

|

| -

Gabz Ortmann-Rodens, Sopran |

|

| -

Helga Hamm-Albrecht, Mezzosopran |

|

| -

Wolfgang Fromme, Kontratenor |

|

| -

Helmut Clemens, Tenor |

|

| -

Hans-Alderich Billig, Baß |

|

| und |

|

| -

Colin Tilney, Cembalo |

|

| -

Pere Ros, Viola da Gamba und

Violine |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Burg

Konradsheim, Konradsheim

(Germania) - 1-4 ottobre 1975 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

128 Q - (1 lp) - durata 43' 28" -

(p) 1976 - Analogico (Quadraphonic) |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63437 2 - (1

cd) - durata 43' 28" - (c) 1991 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26496 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 43' 28" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

La prima

edizione in CD contiene madrigali

di Gesualdo e Monteverdi

registrati nel 1974 e pubblicati

nel 1975 (estranei alla collana

Reflexe).

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the days when

the only way of getting to and

from the Beaver Republic

of Venice was by water, the

favourite route was the one

linking Venice and Padua.

Thanks to the scenic charm of

the journey, but also to the

original company that could be

found amongst the passengers,

the trip on the burchiello

became a remarkable

experience, of which a number

of accounts were written inthe

course of the centuries. It is

therefore likely that this

experience also inspired Pater

Adriano Banchieri, a monk of

Monte Oliveto (near Bologna),

to render it in music when he

went to Venice in 1605 to take

on the post of organist for a

short period at the Convent of

St Helena. In the days when

the only way of getting to and

from the Beaver Republic

of Venice was by water, the

favourite route was the one

linking Venice and Padua.

Thanks to the scenic charm of

the journey, but also to the

original company that could be

found amongst the passengers,

the trip on the burchiello

became a remarkable

experience, of which a number

of accounts were written inthe

course of the centuries. It is

therefore likely that this

experience also inspired Pater

Adriano Banchieri, a monk of

Monte Oliveto (near Bologna),

to render it in music when he

went to Venice in 1605 to take

on the post of organist for a

short period at the Convent of

St Helena.

An important musician,

theorist and writer, Banchieri

was born at Bologna on 3rd

September 1568. His real name

was Tommaso: Adriano was the

name he adopted on entering

his order, which he did at the

age of 19. After receiving

instruction in music since

childhood, he became a pupil

of the highly regarded

Gioseffo Guami at Lucca,

probably in 1592 or 1593.

After organist’s posts at

Imola, Gubbio, Venice and

Verona, he finally returned to

his home town in 1606. There

he associated with many

distinguished musicians and

was the focus of a circle

which formed itself into two

Academies, one after the

other; until 1628, Banchieri

was the Principal of the

second. Hampered in his work

by failing eyesight during the

last years of his life,

Banchieri died of a stroke at

Bologna in 1634.

The Barca di Venetia per

Padova first appeared in

Venice in 1605, but this

version is only incompletely

preserved. The revision

published in 1623 has

considerable differences from

the first edition. Where the

overall disposition is

concerned, the first eight and

the last two numbers stay

where they were. Between them

there were originally two

separate scenes, which were

dovetailed together in the

second version: first, five

consecutive madrigals, and

then the Rizzolina episode.

The madrigals were reduced to

four, of which only two were

from the first edition and

even they were rearranged. The

Rizzolina

episode, on the other hand,

was arnplified

somewhat. In addition,

far-reaching textual

and musical alterations were

made to the various pieces.

The gift for acute observation

and characterisation, and for

formulating them in elegant or

barbed terms, which marks the

wit of the Italian

Renaissance, is also typical

of the humorous works of

Adriano Banchieri to a high

degree. However vivid or, as

quite often drastic the

depiction of the characters

and action may be, the

musical treatment is always

given its full value.

The Umore, who calls

upon both actors and public

alike (I), is often quoted as

an example of this. As with

nearly all the figures who

appear in such works, the

depiction of Umore is

not tied to a particular

voice: the whole company sings

his words, every phrase (and

also individual ideas) being

given its own motif in the

traditional manner according

to what the words express.

The description of the

fishermen and oarsmen on the

Venetian shore (II) is

a fine example of the

aforementioned balance between

vivid illustration and formal

control: the three parts (the

first is repeated after the

second) are written above the

cry of the fishermen (Ostreghe

da bruazzo, etc) which

is sung three times unchanged

as a cantus firmus. Amid the

cries of the crew, the Patrono

takes leave of his Ninetta (III),

with the madrigalesque

emotionalism of the lover’s

complaint in caricaturing

contrast to the setting. The

joyful conclusion in triple

time is the signal for the

company to set off. The

Patrono eggs on the passengers

to pass the time with

amusements (IV); the nasal

syllables here and elsewhere

(e.g. ba - nanana - rca)

are probably a caricature of a

particular manner of singing,

and maybe of the Venetian

dialect as well.

Then a bookseller from

Florence proposes (V) that

tive singers - the normal

contingent for the vocal

chamber music of that day -

volunteer to perform alcune

cappricciate del Banchieri.

A singing teacher from Lucca

(possibly a reminiscence of

Banchieri’s period of study

there) seconds the proposal

(VI), chiming

in with the solfeggio scales

that were always the attribute

of singers until well into the

19th century. The five singers

are got together (VII) - four

Italians from various regions,

and a German capable of broken

Italian. One after another

they introduce themselves,

each in his own dialect and

with his own manner of

singing. The witty

juxtaposition of dialects had

been a set custom since the

14th century, and the picture

of the tippling Northerner was

also part of the permanent

repertoire. The following

number (VIII), like No II, is

written above the cantus

tirmus (repeated four times)

of the quaffing German, who

begins and ends it by himself,

lurching along as it were

musically too. Two seriously

meant madrigals follow (IX-X)

in the style of Carlo Gesualdo

da Venosa; later on, others in

the manner of Luca Marenzio

(XIV) and Donato Antonio Spano

(IV), a Neapolitan

contemporary of Banchieri. Yet

another piece is modelled on

Enrico Radesca,

of Turin. How

these allusions are to be

understood, however, is hard

to explain satisfactorily.

They can scarcely be intended

as superficial imitations,

still less as parodies, as one

would then expect hard

chromatic progressions in the

case of Gesualdo, an opening

with accentuated exclamation

in the case of Marenzio, and

so on. At all events,

Banchieri employs the madrigal

style of his day, with much

use of the diminished fourths

generally

associated with lovers’

complaints (already parodied

in No III)

and with texts partly by the

popular Giovanni Battista

Guarini.

The madrigal scene is

interrupted and then submerged

by the merry goings-on

centring on the fair

Rizzolina. The first ot these

scenes (XI-XIII) is

held together by the balletto

retrain Fa-la-la

or La-trai-nai-nai. Rizzolina

is presented first on her own,

as a kind of precentor

answered by the chorus (in the

manner of the French airs de

cour); then with her lover

Orazio in a duet for upper and

lower voices. A Jewish couple

who have come aboard say their

prayers, singing the Hebrew

texts (which are in part

only suggested in sound) in

canon, while the tenor keeps

repeating the vvord la

sinagoga

as a kind of cantus firmus.

The second Rizzolina scene

begins (XVI-XVII) with eight

verses of a song, of which

four

are sung by Rizzolina and four

by Orazio, while the remaining

four

voices (the soloist who is not

at the moment acting as

precentor sings the uppermost

part) imitate the lute

accompaniment with

onomatopoeic syllables. When,

finally, a string breaks, the

“lute” accompaniment in the

next piece (XVIII) is reduced

to three voices, as the two

soloists sing four more verses

(each sings the same one

twice), again in canon.

Arrival, payment of the fare,

and disembarkation, are

rounded off (XIX) with the

balletto refrain (already

familiar from Nos XI and

XIII), which also concludes

the actual voyage.

The Epilogue, with the begging

of the fake soldier (XX), may

allude to actual events, as

many Italians served in the

Emperors campaigns against the

Turks.

Theophil

Antonicek

(Translation:

David Potter)

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|