|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 124 - (p) 1974

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26493 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

1 CD -

CDM 7 63426 2 - (c) 1990

|

|

| GUILLAUME

DUFAY (1400-1474) - Adieu m'amour

(Chansons und Motetten) |

|

|

|

|

|

| - Bon jour, bon

moys, bo·e sepmayne |

3' 00" |

|

| - Helas mon

dueil, a ce cop sui ie mort |

2' 58" |

|

| - Pour l'amour

de ma doulce amye |

3' 36" |

|

| - Ce moys de may |

2' 15" |

|

| - Se la face ay

pale |

3' 21" |

|

| - J'atendray |

1' 48" |

|

| - Craindre vous

vueil |

4' 34" |

|

| - Ce jour de

l'an |

1' 42" |

|

| - Adieu m'amour |

5' 58" |

|

|

|

|

| - Vergene belle |

3' 43" |

|

| - Quel fronte

signorile in paradiso |

2' 44" |

|

| - Mirandas parti

haec urbs florentina puellas |

3' 33" |

|

| - Magnanimae |

3' 56" |

|

| - O gemma, lux

et speculum |

3' 05" |

|

| - Christe,

redemptor omnium |

4' 27" |

|

|

|

|

STUDIO DER FRÜHEN

MUSIK / Thomas Binkley, Leitung

|

|

| -

Thomas Binkley, Laute, Citol,

Duoçaine, Flöte, Gittern |

|

| -

Sterling Jones, Rebec, Fidel,

Citol, Douçaine, Regal |

|

| -

Andrea von Ramm, Gesang, Harfe,

Organetto |

|

| unter

Mitwirkung von |

|

| -

David Kehoe, Gesang |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bürgerbräu.

München (Germania) - 1-3 maggio

1973

Munstermuseum, Basel (Svizzera) -

17 giugno 1974

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

124 - (1 lp) - durata 52' 09" -

(p) 1974 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63426 2 - (1

cd) - durata 52' 11" - (c) 1990 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26493 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 52' 09" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Guillaume

Dufay (1400-1474) -

Chansons und Motets Guillaume

Dufay (1400-1474) -

Chansons und Motets

No other priest ever

wrote so many love songs as

did Guillaume Dufay. Who was

he? Why does he capture our

attention?

There are a few creative

artists in the course of the

last several centuries, who

seem to have a special

significance. Everyone has

heard of Dante, not everyone

has heard of Sacchetti. The

reason is not simply that

Dante is a better poet, it is

that he became the symbol of a

period in literary history,

the one whose works are

considered the main event of

the period.

Such an artist is Dufay, whose

name is far better known than

his works. Dufay is the

composer we are led to

associate with the Burgundian

court in the 15th century, a

lavish court with a glamorous

history, a court often held to

play the central cultural role

in the period (c.f. Huizinga,

Waning of the Middle Ages),

a court with which more than

ten composers were intimely

associated, including some

very well known, such as

Binchois, Hayne and Busnois.

Dufay was born in France about

the year 1400, and by the time

he was 20 he was in Italy,

writing music for the

Malatestas. Three pieces for

this family are dated 1420,

1423 and 1426. 1427 he was in

Bologna, and in that city the

following year he was ordained

a priest. He then spent some

years as a singer in the Papal

choir in Rome. 1437 he worked

in Ferrara, and the next year

he went to work at the court

of Savoy. In

his will Dufay mentions that

he spent some seven years in

their service that would be

from 1438-1445. That makes him

about 45 years old. The

following year a document

naming him as a canon at St.

Wandru in Mons

gives him for the first time

the title of Burgundian

chapelmaster, clearly an

honorary title for thus far in

his career he has been busy

elsewhere. From 1451 on he

lived in Cambrai and travelled

a great deal. He died then

1474, leaving behind over 200

compositions in the sacred and

secular spheres. We see that

the Burgundian court plays

very ittle role in his

biography.

We see also that our

song-writing priest was

clearly a composer by

profession, becoming a priest

much as some composers today

acquire academic status - only

as a matter of elegibility. As

a composer he had such force

as to become for music what

Jan van Eyck, his

contemporary, became for

painting. There was no

collected work" edition of

his music during his lifetime,

as both Machaut

and Wolkenstein before him had

seen realized. However, his

name is omnipresent in the

manuscript sources of the 15th

century, both in the central

Burgundian chansons and the

peripheral sources from Italy,

Austria and Germany, etc..

It is

this presence in such an

unusual number of sources from

all over Europe, a presence

thouroughly warranted by his

reputation, that made him the

symbol of 15th century music

for us. And it is only human

that we wish to associate this

composer

whose works were in the 15th

century most widely

disseminated, primarily with

the large and most influencial

and secular court of Burgundy,

even if there is very little

connection at all.

As we are dealing with a

selection from a large

repertory we cannot present a

statistical representation of

Dufays over five-score

secular songs and many other

compositions. We decided to

limit our selection to pieces

designed for small ensemble,

pieces generally of a solistic

character, pieces which

reflect some specific artistic

attitude, pieces which

themselves occupy some

specific historical pitch.

No other chanson of Dufay is

represented in as many

sources, the runner-up is Se

la face ay pale, also a

very famous piece represented

in nine sources. This last is

a ballade équivoque,

in which the last syllable of

each line is the same, but has

each time a different meaning.

Dufay himself based a mass on

this chanson. This is not the

place for a detailed

discussion of the works,

although a word about the

forms may aid the listener in

grasping certain important

aspects of the music. The

motets, for example,

frequently employ this

structure:

- introduction (vocal) lst

section (with instrumental

isorhythmic tenor)

- 2nd

section (new pitches, same

rhythm)

- 3rd section (the isorhythmic

tenor is in smaller

note-values, quickening the

tempo by one third)

The motets, of course,

following the 13th-14th

century tradition always have

two texts going on at once,

and the melodic character of

the vocal lines is not

song-like, but composed of

rhythmic cells which together

present a sound-picture which

is difficult to grasp. This is

music which progresses and

moves forward, and does not

look back. Not so with the

chansons. Here the structural

principle is reiteration.

Three structures account for

most of the chansons: (letters

mean musical sections, capital

letters mean that section is

sung with the very same text)

- Virelai (the fewest): A bb a

A

- Ballade: a a b (with envoy

in final stroph)

- Rondeau (the most): A B a A

a b A B

The envoy at the close

of a ballade is simply a

repeat of the last few musical

phrases with new text. The

idea is to bring the work to a

definite close, similar to the

conclusion of the rondeau

or virelai. The virelai

accomplishes this by repeating

the first line of text and

music, the rondeau the

first two lines of text and

music.

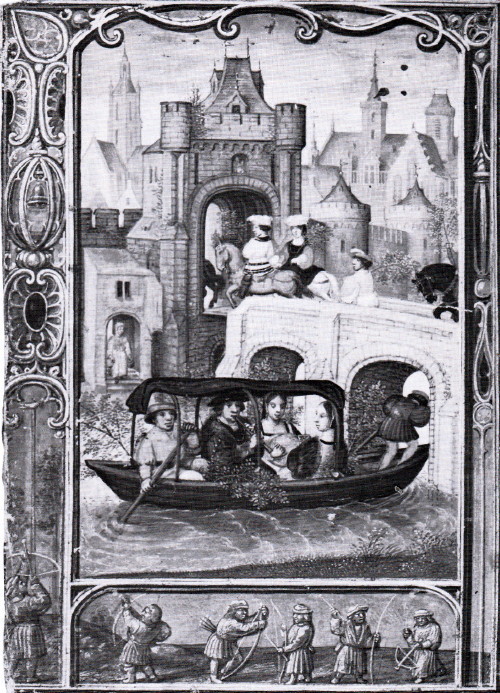

Within these fixed structures

is a world of detail, of

balances, of intriguing

relationships, as disguised as

the tiny birds in bushes of a

Flemish landscape. The texts

are not to be taken too

seriously; they are seldom of

the literary quality we expect

from Machaut,

the trouveres or the

troubadours. The musical

architecture has largely

replaced the literary element

here, so we must focus on

musical detail.

Thomas

Binkley

The

instruments employed are the

instruments of the period:

- Rebec: Eugen

Springer, Frankfurt

- Rebec:

Fabrizio

Reginato, Fonte Alto (Tv)

Italy

- Vielle: Fabrizio

Reginato, Fonte Alto

(Tv) Italy

- Vielle:

Fabrizio

Reginato, Fonte

Alto (Tv) Italy

-

Luter: maker

unknown

-

Luter: Fabrizio Reginato, Fonte Alto (Tv) Italy

-

Harp: Franz

Novy, Vienna

-

Gittern: Fabrizio Reginato, Fonte Alto (Tv) Italy

-

Psaltery:

maker unknown

-

Douçaine: Günter

Körber,

Berlin

-

Flute

(Recorder):

von Huene,

Boston, USA

-

Regal: Mads

Kjersgaard, Upsala,

Sweden

-

Organetto:

Ahrend &

Brunzema, Loga

bei Leer,

Germany

Tambourin:

A.T.

Camposarcone,

London

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|