|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 120 - (p) 1974

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26489 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| WILLIAM BYRD

(1543-1623) - Harpsichord Music |

|

|

|

|

|

| - Pavan and

Galliard in G - MB 72 a und b)

* |

5' 13" |

|

| - Fantasia in D

minor - (MB 1) * |

5' 42" |

|

| - Lachrymae

Pavan - (MB 54) ** |

5' 14" |

|

| - Galliard in D

minor 4' - (MB 53) ** |

1' 50" |

|

| -

Hugh Aston's Ground - (MB 20)

* |

8' 33" |

|

|

|

|

| - Prelude in C

- (MB 24) ** |

4' 09" |

|

|

| - Mistress Mary

Brownlow's Galliard - (MB 34)

** |

|

|

|

| - The Quadran

Pavan - (MB 70a) * |

9' 04" |

|

| -

The Quadran Galliard - (MB

70b) * |

4' 48" |

|

| - Pavan and

Galliard in C minor - (MB 31a

und b) ** |

6' 05" |

|

| - Coranto in C

4' ** |

1' 36" |

|

|

|

|

| Colin Tilney,

Cembalo und Virginale |

|

|

|

| MB

= Musica Britannica |

|

| *

= Italienisches Cembalo (17. Jhdt.,

unsigniert) |

|

| **

= Flämisches Virginal von Martinus

van der Biest, Antwerpen |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Germanischen

Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg

(Germania) - 1-4 luglio 1974 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

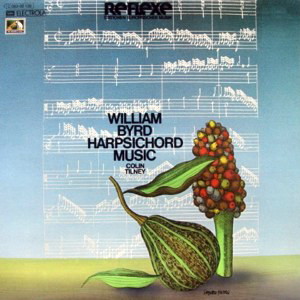

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

120 - (1 lp) - durata 52' 26" -

(p) 1974 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26489 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 52' 26" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

William Byrd

(1543-1623)

In a

Golden Age true gold becomes

devalued. As plants in very

fertile soil spread out and

rob each other of the sun, so

contemporary artists of real

greatness tend to some extent

to mask each other's

achievements. Haydn

would

undoubtedly have shone

brighter in the Vienna of 1750

then he could forty years

later beside the very

different accomplishments of

Mozart and Beethoven, and

William Byrd has also paid the

penalty of living at a time of

excessive supply, that amazing

age we call Elizabethan,

although it stretched well

into the reign of her

successor, James I. For

us, Byrd is a great pioneer, a

towering bridge between post-Reformation

polyphony and the newer, more

keenly harmonic, visions of

the seventeenth century, but

we name him in the same breath

as his fellow writers for

voices, viols and virginals,

all of them younger and not

one his equal in expressive

power, versatility or sheer

musical invention.

It is a

mistake these younger men

themselves did not make. For

them, Byrd was in no sense primus

inter pares: they called

him, rather, Brittanfcae

Musicae Parens, “a man

never without reverence to be

named of the musicians”, and

claimed that “in Europe is

none like to our English man:

with fingers and with pen he

hath not now his peer". To

discount Lassus is bold -

Monteverdi was little known in

England in 1591 -, but who at

home could have sustained a

challenge against Byrd’s

supremacy? Dowland, Morley,

Bull, Farnaby, Weelkes,

Ferrabosco, Campion, Gibbons,

Tomkins - the names are

inexhaustible and glorious,

taken together, byt all except

Morley and Gibbons excelled in

one particular skill, whether

it was lute-song, consort

music, madrigal, church

settings or keyboard writing,

and lack the overall range of

confident mastery that we find

in Byrd. He

is the vhole man, praised for

his learning and for his

performance, respected for his

lifelong refusal to abandon

his Catholic faith, and loved

for his upright character and

for his generous attitude to

his colleagues and friends.

Some such appreciation of

Byrd’s value as a human being

must lie behind the eulogy

that Henry Peacham wrote in The

Compleat Gentleman

in 1622, the last full year of

Byrd’s life, when he had

outlived many of his pupils

and become a revered national

figure: “For Motetts and

Musicke of pietie and devotion

as well for the honour of our

Nation, as the merit of the

man, I prefer above all our Phoenix

M. William Byrd, whom in that

kind I know not whether any

may equall".

Byrd’s masses, motets and

liturgical settings represent

by far the largest part of his

output, and a critic could not

have passed them by in silence

for their very number, even if

it were not obvious that for

Byrd, as for Bach, the worship

of God was the kernel of his

existence. Yet, a little later

on, Peacham does justice also

to Byrd’s secular vocal

writing: “being of him selfe

naturally disposed to Gravitie

and Pietie, his veine is not

so much for light Madrigals or

Canzonets, yet his Virginella

and some others in his first

Set cannot be mended [i.e.

bettered] by the best Italian

of them all". In

fact, the three published

volumes of 1588, 1589 and 1611

contain some of the best of

all English madrigals, and the

fifty or so unpublished songs

for solo voice and viol

accompaniment are both

beautiful and innovatory.

Words, whether sacred or

profane, were always Byrd’s

most central concern, and his

admirers responded with relish

to his response. In the

preface to the 1605 Gradualia

Byrd himself reveals something

of the creative process:

“Moreover, in these words, as

I have

learned by trial, there is

such a profound and hidden

power that to one thinking

upon things divine and

diligently and earnestly

pondering them, all the

fittest numbers occur as il of

themselves and freely offer

themselves to the mind which

is not indolent or inert".

Byrd was appointed organist of

Lincoln Cathedral in 1563, and

from 1570 until the end of his

life

served as one of the organists

of the Chapel Royal. in both

posts he must have trained

choristers, in addition to

supplying sung music tor the

services, so his deep interest

in the human voice should not

surprise us, nor should we

forget that it lies at the

root of

his instrumental music as well.

There are no direct

transcriptions of chansons or

motets among Byrd’s keyboard

works; such lifeless copying

would have offended his acute

sense of instrumental idiom.

But every moving part in one

of his fantasies or pavans is

a wordless

voice, having different

registers and needing breath.

Equal in importance with words

to Byrd was form. After a few

early organ pieces, probably

influenced by the work of his

teacher, Thomas Tallis, Byrd

abandoned cantus

firmus writing, the

traditional means of

constructing abstract music on

a large scale, and developed

such forms as the sectional

fantasy, the folksong

variation and, above all, the

ground. Apart from the great

sets on the passamezzo

antico (Passing mesures)

and the passamezzo moderno

(Quadran - in G major, with B

natural or “quadro”), Byrd

rarely used the common

European grounds (Folia, Be di

Spagna, Ruggiero),

preferring either his own

invention or formulae such as

the one attributed to Hugh

Aston. For shorter pieces Byrd

adapted the sort of dances

(notably the pavan and

galliard pair) that were

written for viol consort and

are already found worked out

for keyboard in sources such

as the Mulliner Book and the

Dublin Virginal MS. “Lachrymae”

is a keyboard elaboration of

the famous song by John

Dowland, first printed by

William Barley in 1596; here,

as in almost everything he

wrote, Byrd’s lyrical feeling,

restraint and delicacy of

taste stamp his work as quite

exceptional and beyond

comparison with any other

artist of the age, at least in

EngIand. William

Byrd, "homo memorabilis".

The concept “English Virginal

Music” not only obscures the

flavour of the various

composers it embraces (Byrd

especially), but also gives

rise to confusion about the

instrument the music was

played on. Surviving English

virginals proper date only

from the midseventeenth

century, but the word

“virginal” seems to have meant

any keyboard instrument except

the organ, and Byrd and his contemporaries

must have used a wide range of

Italian and Flemish imports:

harpsichords, claviorgana,

oblong and polygonal virginals

and spinets, perhaps even

clavichords.

Colin

Tilney

About

the Instruments

In the

second half ot the 16th and

the first

half ot the 17th century the

art of music composed for

domestic keyboard instruments

rose to its climax in England.

Those numerous English

composers that wrote

works tor these instruments

are all knovvn under the name

of virginalists. Up to

about 1660 any type of

harpsichord - harpsichord

proper, clavicytherium,

virginal or spinet - was

called virginal. Only from

about 1660

onwards was

the term harpsichord

used, the term virgfna/ being

limited to virginal and

spinet. Thus these

virginalists are composers

that composed for the

harpsiohord.

At the time ot

the virginalists there must

have been a great number of

harpsichords to perfom

these works. The tact is

that the inventory of

instruments owned by King

Henry VIII, who had a great

gift

for

music, contains an amazingly

large number of

keyboard instruments. Queen

Elizabeth as well has played

the virginal. But

this does not imply that all

these harpsichords favoured

as they were have been of

English origin. In

the 16th century, it is

true, there are known the

names of 16 harpsichord

makers in England, but at

least some ot them give the

impression that their

bearers immigrated to

England. In the Victoria

& Albert Museum there is

a harpsichord dating from

the year 1579, made in

London by a local

harpsichord maker, whose

name was Lodewijk

Theeuwes and who was of

Flemish descent. In this

museum there is also a

spinet that is said to have

been in the possession of

Queen Elizabeth I. It is

beyond all doubt a Italian

instrument. The oldest

hapsichord preserved of definite

English origin dates from

1622. Without doubt the

English virginal-players did

not only use autochthonous

instruments, but also

imported them from Italy and

Flanders. Thus history gives

reason for the fact

that an English and an

Flemish keyboard instrument

have been used for

this recording. The Italian

instrument is an unsigned

and undated harpsichord

which on account of

certain characteristics

suggests the probability

that it was made in the

mid-17th century. Apart from

two devices to vary the

timbre - which, by the way,

are not used in this

recording - the instrument

is exceptionally

conservative, so that one

may suppose its sound to be

most similar to that of the

instruments that were used

in Byrd’s lifetime.

The Flemish instrument comes

from the workshop of

Martinus van der Biest and

was made in 1580. It is an

instrument that is called virginal

according to the German

terminology.

In

such an instrument the strings

lie horizontally, but parallel

to the keyboard. Contrary to

the wing-shaped

spinet the virginal is oblong

and rectangular in shape. The

harpsichord used here is not

the usual type, but a

double-virginal. With the

Antwerp speciality the keys

are on one (here the lett)

side, whereas the key-free

side (here on the right) can

hold an octave-virginal. This

ottavino may also be placed on

the big instrument and both

are coupled, so that the pitch

on the keyboard below is

8-foot/4-foot.

Two works ot this recording

are performed on the

double-virginal in this way:

Galliard in D minor (Side 1)

and Coranto in C major (Side

2).

The instruments used here form

part of the

collection of

old instruments in the German

National Museum,

Nuremberg. The Italian

harpsichord is owned by Dr.

Dr. h. c. Ulrich Rück

and forms part of his

collection of

historical instruments. In this

recording both instruments are

mean-tone tuned.

John

Henry van der Meer

Translation

by Gudrun Meier

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|