|

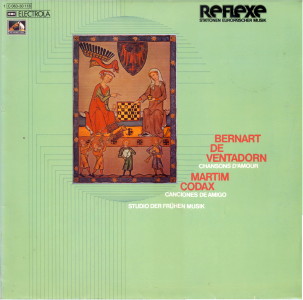

1 LP -

1C 063-30 118 - (p) 1973

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26486 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| Bernart

de Ventadorn - Martim Codax |

|

|

|

|

|

| MARTIM CODAX

(13. Jhdt.) |

|

|

| Siete canciones de

amigo - 2 Singstimmen,

Organetto, Laute, Fiedel, Flöte,

Schlagzeug |

|

|

| 1. Ondas do mar

de vigo |

3' 11" |

|

| 2. Mandad ei

comigo ca ven meu amigo |

3' 16" |

|

| 3. Mia ýrmana

fremosa treidos comigo |

2' 30" |

|

| 4. Aý deus se

sab ora meu amigo |

5' 20" |

|

| 5.

Quantas sabedas amae amigo |

2' 00" |

|

| 6.

Eno sagrado en vigo |

4' 27" |

|

| 7.

Y ondas que eu vin veero |

2' 45" |

|

|

|

|

| Bernart

de Ventadorn (12. Jhdt.) |

|

|

Chansons d'amour

|

|

|

| - Ab joi mou le

vers e.I momens - 2

Singstimmen, Organetto,

Psalterium, Chitarra

sarazenica, Rebec, Lira,

Schlagzeug |

14' 02" |

|

| - Poi preyatz

me, snhor - 2 Singstimmen,

Laute, Lira |

12' 00" |

|

|

|

|

STUDIO DER FRÜHEN

MUSIK / Thomas Binkley, Leitung

|

|

| -

Andrea von Ramm, Sängerin |

|

| -

Richard Levitt, Sänger |

|

| -

Sterling Jones, Streichinstrumente |

|

| -

Thomas Binkley, Zupfinsrumente |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bürgerbräu.

München (Germania) - maggio 1973 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann Nikolaus Matthies

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

118 - (1 lp) - durata 49' 31" -

(p) 1973 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26486 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 49' 31" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

THE

TECHNIQUE OF

PLAYING MONOPHONIC MUSIC

The question

of performance style warrants

some comment, because it is

this more than anything else

that enables the musician

today to come to grips with

very early music, and it is an

understanding of this that

enables the listener to enter

critically into this world of

art.

We are accustomed to expect

the musical score to reflect

fairly precisely the sound of

a performance; even allowing

for a bit of improvisation

here and there, we expect the

general flow of the music to

be what is notated in the

score. This is essentially

true of Western music from

about 1300 on, beginning with

polyphonic music. It is

not true of monophonic music.

The secular song of the

Troubadours and the Juglares

and many others was

expressed on paper

only in terms of the text and

the melody, while its

expression in sound

was quite something else. Each

region, or at least many

regions, developed performance

styles of their own, which

means that the same song was

performed differently in

different places or under

different circumstances.

The singing style is one thing

that changed from place to

place, the sort of

improvisation is another, and

the choice of accompanying

instruments another. Even the

very idea behind the

performance, whether a

spontaneous performance or a

carefully arranged show for

invited guests, had a

significant influence on the

resultant sound.

What we have here is the sort

of thing the professional

musicians at a wealthy court

in southern France and in

northern Spain made of this

material. The instrumental

prelude tries to attract

attention to the performance,

establishes the tonality and

general aesthetic level of the

song. The strophes are

separated by interludes which

serve as a diversion. The

accompaniments are in

different styles, now in

dialogue with the singer, now

providing an accoustical

background, now

moving with the singer along

the same line. The guiding

factor in the instrumental

work is the playing technique

of the instruments involved.

Each instrumentalist tries to

bring the essence of his

instrument into play, to be

sure, within the bounds of a

chosen style but without

subordinating the

chracteristics of the

instrument to contrapuntal

ideology.

MARTIM

CODAX

Martim Codax,

the early 13th century

Galician juglar has

left us in his Siete

Canciones de Amigo, his

Seven Songs of Love the

earliest surviving examples of

Iberian secular Music.

We know very littly about the

man, nor do we completely

understand how he came to

write these songs as a cycle

(no other song cycles are

known from this period).

The setting is the town of

Vigo, located on the Atlantic

coast of Spain just above the

Portuguese border, and well

known today for its excellent

cuisine of fish and mollosks.

In the

13th century, one came to Vigo

by way of two routes: one was

the Camino de Santiago, the

Pilgrim Road, called the

Camino Francés,

because it led from France

across the whole of the North

of Spain (viz. El Camino

de Santiago 1C O63-30

107 and 1C 063-30 108). The

other route to Vigo was the

Sea.

Today, ships come from far and

wide, loading and unloading

goods, bringing and taking

away travellers; today, the ondas

do mar, the waves of the

sea drifting towards an

industrial town no longer

suggest a poetic image, no

longer contain a mystery of

completely unknown qualities.

But in the 13th century no

ships came from around the

world to dock at Vigo, because

then the world was flat, and

the sea surrounded the only

piece of land there was, and

the sea led

out to a great nothingness beyond,

a darkness and emptiness

feared by

all men.

For Martim Codax the sea at

Vigo was the end of the world,

and it was never certain that

who sailied away from that

shore would not fall off the

edge of the world never to

return. That then is the

emptiness of this lover who

waits by

the church on the hill

overlooking the sea at Vigo,

waiting for his (or her)

belovod, not understanding why

she (he) does not come.

BERNART

DE VENTADORN

Bernart de

Ventadorn was a troubadour,

which we hasten to point out

was not really a profession

but an activity which was a

part of and which reflected a

particular life style.

Those familiar with France

will know the Limousin, but

few will know the town of

Egletons, which is the closest

rail connection to the ruins

of the once very impressive

castle of Ventadorn.

Enviable were those

inhabitants of the Languedoc

in the 12th century, for life

then was cosy in the South of

France. The art of the

troubadours flourished in the

warm sun and gendered a

particular cultural ambiance

in the courts of the nobility,

where love of beauty, of

music, of poetry and women

were central to the creative

and recreative life.

We think of the Count of

Poitiers, Peire Vidal, of

Bertrand de Born, P. de

Auvergne, G. de Bornelh, etc.

etc. but of the many

troubadours and the thousands

of poems and songs they have

left us, Bernart de Ventadorn

and his five-dozen songs are

classic.

Only in one attribute is

Bernart not typical of his

colleagues: he was of low

birth, son of an archer and

the woman who fired the

bake-ovens at the castle of

Ventadorn. Yet Bernart came to

be accepted into the house of

his benefactor, the viscount

of Ventadorn, who himself was

a singer and poet and may have

been Bernart’s teacher. The

viscount had an attractive

wife who - according to the

vida - was the cause of some

considerable difficulty for

herself and for Bernart, but

there is not a shread of

evidence to support that

contention. It is true, to be

sure, that Bernart left his

comfortable Ventadorn

involuntarily, and, practiced

in the art of courtly love and

courtly poetry, soon found a

place at the court of Eleanore

of Acquitaine, reina dels

Normans, wife (at that

time) to Henry II of

England.

Bernart spent some time in

Normandy and then went with

the queen to England where he

stayed at least for two years.

There it was where he wrote Pois

preyatz me, senhor... to

his distant Asziman, the

otherwise nameless object of

his earlier attentions.

Needless to say, Asziman was

not the sole object of Bernart’s

attentions, but an early and

revered one. Bels-Vezers was

another (Ab joi meu...),

who some contend was the wife

of the Count of Vienne and

others say was the wife of

Raimon V, Count of Toulouse

whose name was Constance. What

does it matter who she was.

Bernart disguised the names of

his loves effectively,

even employing the masculine

gender on occasion. Bernart de

Ventadorn began to write

poetry about 1140 and he died

before 1194. All of his poems

are love poems of a personal

nature, of which the two

selected here are quite

typical.

Thomas

Binkley

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|