|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 112 - (p) 1973

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26479 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63444 2 - (1991) |

|

Venezianische Mehrchörigkeit

|

|

|

|

|

|

Salomone

Rossi (1570?-1630?)

|

|

|

Tanzsätze

zu fünf Stimmen (erschienen

1607/08)

|

6' 27" |

|

| -

Vier Blockflöten, Fagott, zwei

Pommen, zwei Posaunen,

zwei Violinen, zwei Violen, Viola

da gamba, Violone, Gitarre,

Cembalo, Orgelpositiv |

|

|

|

|

|

| Orlando di

Lasso (Roland de Lassus)

(1532-1594) |

|

|

| I. Hor che la

nuova e vaga primavera

(erschienen 1575) - Madrigale zu

10 Stimmen in zwei Chören |

2' 51" |

|

| - Chor I: kleiner

Chor, vier Blockflöten, Fagott, Cembalo,

Laute |

|

|

| - Chor II:

großer Chor, zwei Violinen, zwei

Violen, Viola da gamba, Violone,

Orgelpositiv |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cesario Gussago (gest. 1611?) |

|

|

| Sonata "La

Leona" (erschienen 1608) zu

acht Stimmen in zwei Chören |

3' 25"

|

|

| - Chor I: Zink,

drei Blockflöten, Fagott, Orgelpositiv |

|

|

| - Chor II:

zwei Violinen, Viola, Viola da gamba,

Violone, Gitarre, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Giovanni Gabrieli (1557-1612) |

|

|

| Canzone

(erschienen 1615) zu zwölf Stimmen

in drei Chören |

5' 07" |

|

| - Chor I: drei

Blockflöten, Fagott, Gitarre |

|

|

| - Chor II:

zwei Pommen, zwei Posaunen,

Orgelpositiv |

|

|

| - Chor III:

zwei Violinen, Viola, Viola da gamba,

Violone, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Giovanni Croce (Joanne a

Cruce Clodiensis) (1557-1609) |

|

|

| II. Dialogo de

Chori d'Angeli (erschienen

1586) - Geistliche Madrigale zu

zehn Stimmen in zwei Chören |

3' 16" |

|

| - Chor I: kleiner

Chor, Gitarre, Cembalo, Fagott |

|

|

| - Chor II:

großer Chor, Orgelpositiv, Viola da

gamba, Violone |

|

|

|

|

|

| Claudio

Bramieri (gest. vor 1595) |

|

|

| Canzone "La

Foccara" (erschienen 1599)

zu acht Stimmen in zwei Chören |

4' 00" |

|

| - Chor I: drei

Blockflöten, Fagott, Orgelpositiv |

|

|

| - Chor II:

zwei Violinen, Viola, Viola da gamba,

Violone, Gitarre |

|

|

|

|

|

| Orlando di

Lasso (Roland de Lassus)

(1532-1594) |

|

|

| III. Trionfo del

Tempo (erschienen 1584) -

Madrigal zu zehn Stimmen in zwei

Chören |

2' 17" |

|

| - Chor I: Solosopran,

Blockflöte, Chor,Cembalo, Dulzian,

Laute |

|

|

| - Chor II:

Solosopran, Blockflöte, Chor, zwei

Violinen, Viola, Viola da gamba,

Violone, Orgelpositiv |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tiburtio Massaino (Massaini)

(16.-17. Jahrhdt.) |

|

|

| Canzone Nr.

XXXIV (erschienen 1608) zu

acht Stimmen in zwei Chören |

2' 46" |

|

| - Chor I: Zink,

Violine, Viola, Viola da gamba, Laute

|

|

|

| - Chor II:

Cembalo, Orgelpositiv, Violone |

|

|

|

|

|

| Andrea Gabrieli (1520-1586) |

|

|

| IV. O passi

sparsi (erschienen 1587) -

Madrigal zu zwölf Stimmen in zwei

Chören |

5' 00" |

|

| - Chor I: Singstimmen, zwei

Violinen, Viola da gamba, Cembalo |

|

|

| - Chor II:

Zink, Baßblockflöte, Altblockflöte,

Dulzian, zwei Posaunen, Violone,

Orgelpositiv |

|

|

|

|

|

| Giovanni Battista Grillo

(gest. 1622) |

|

|

| Canzone

(erschienen 1608) zu acht Stimmen

in zwei Chören |

4' 59" |

|

| - Chor I: Tenorblockflöten,

zwei Violinen, Viola da gamba, Gitarre,

Cembalo |

|

|

| - Chor II:

Dulzian, Viola, zwei Posaunen,

Orgelpositiv |

|

|

|

|

|

| Giovanni Gabrieli (1557-1612) |

|

|

| V. Omnes Gentes

("Sacrae Symphoniae", erschienen

1597) - Motette zu sechzehn

Stimmen in vier Chören |

4' 47" |

|

| - Chor I: Singstimmen

a capella |

|

|

| - Chor II:

Singstimmen a capella |

|

|

| - Chor III:

oberste Stimme gesunge, Pommer, zwei

Posaunen, Dulzian |

|

|

| - Chor IV:

drei Blockflöten, zwei Violinen, Viola

und Viola da gamba |

|

|

| - Continuo:

Laute, Cembalo, Orgelpositiv, Violone |

|

|

|

|

|

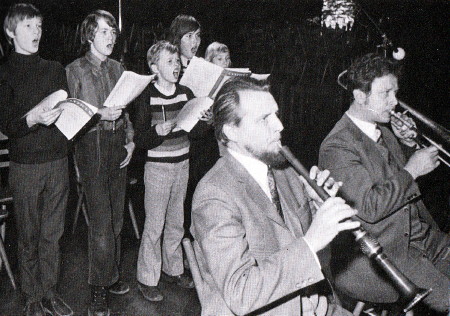

| TÖLZER KNABENCHOR

/ Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden, Einstudierung |

|

| LINDE-CONSORT

/ Hans-Martin Linde, Leitung |

|

| -

Peter Jenne, Annegret Schaub, Conrad

Steinmann, Verena Zacher, Blockflöte |

|

| -

Walter Stiftner, Dulzian,

Barockfagott |

|

| -

Edward H. Tarr, Zink |

|

| -

Alfred Sous, Helmut Schaarschmidt, Pommer |

|

| -

Heinrich Huber, Friedrich Werhahn,

Barockposaune |

|

| -

Herbert Höver, Miguel de la Fuente,

Barockvioline |

|

| -

Christoph Day, Dorothea Jappe, Barockviola |

|

| -

Michael Jappe, Viola da gamba |

|

| -

Angelo Viale, Violone |

|

| -

Konrad Ragossnig, Laute, Gitarre |

|

| -

Rudolf Scheidegger, Cembalo |

|

| -

Eduard Müller, Orgelpositiv |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bürgerbräu,

München (Germania) - gennaio 1973 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

112 - (1 lp) - durata 45' 21" -

(p) 1973 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 634449 2 - (1

cd) - durata 45' 21" - (c) 1991 -

ADD |

|

|

Edition CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26479 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 45' 21" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

A visitor to

Venice in 1608, hearing

polychoral music for the

first time, felt he was

“transported to the third

heaven, like St. Paul.” At

about the same date, the

secretary of the Queen of

France reported that “the

church was filled with

magnificent harmony at a

concert of vocal and

instrumental music given by

the finest local musicians,

mainly on six portable

organs, also on the

excellent main organ, on

trumpets and bassoons,

oboes, viols, violoni, lutes,

cornets, recorders and

flutes.” Many North Italian

composers had abandoned the

severe contrapuntal style in

favour of a more homophonic

and sonorous music. Gioseffo

Zarlino, the distinguished

director of music at San Marco

from 1565 to 1590, felt

constrained to refer the

traditionalists (who were

mainly to be found among the

theoreticians) to the

convincing results produced

in practice. He points out

the characteristics and

virtues of the new style,

and speaks of the grouping

of two or more choirs: “Each

choir is divided into four

or more parts. First one

choir will sing and then

another, or they will

alternate; and occasionally

they all sing together, and

this is highly effective." A visitor to

Venice in 1608, hearing

polychoral music for the

first time, felt he was

“transported to the third

heaven, like St. Paul.” At

about the same date, the

secretary of the Queen of

France reported that “the

church was filled with

magnificent harmony at a

concert of vocal and

instrumental music given by

the finest local musicians,

mainly on six portable

organs, also on the

excellent main organ, on

trumpets and bassoons,

oboes, viols, violoni, lutes,

cornets, recorders and

flutes.” Many North Italian

composers had abandoned the

severe contrapuntal style in

favour of a more homophonic

and sonorous music. Gioseffo

Zarlino, the distinguished

director of music at San Marco

from 1565 to 1590, felt

constrained to refer the

traditionalists (who were

mainly to be found among the

theoreticians) to the

convincing results produced

in practice. He points out

the characteristics and

virtues of the new style,

and speaks of the grouping

of two or more choirs: “Each

choir is divided into four

or more parts. First one

choir will sing and then

another, or they will

alternate; and occasionally

they all sing together, and

this is highly effective."

The most striking feature of

polychoral music is its

sound, which as it were

divides up the space and

spans it at the same time.

The changed dimensions of

the Copernican universe, and

the contrasting of infinity

and human limitations by

theologians and

philosophers, had introduced

new concepts of space. The

opening-out of the visible

and invisible world also

found expression in the

arts. Painters used

perspective and its effect

on the eye of the viewer.

Architects brought the

various parts of a large

space into relationship

with each other, and

proportion

and function played an

essential role. And the

composers produced an

entirely new aural

experience by

positioning groups of

players and singers at

different points.

Heinrich Besseler (in

"Musik und Raum," 1928)

describes the resultant

sonority as "a

reaching-out of word and

sound across a vast and

superhuman space."

It

was the task of the

director of music to

produce a balance of

sound between singers

and players and an

audible contrast

between the various

groups, and quite

often itwas also up to

him to divide up the

score between

different choirs. The

composer always

indicated that his

work was to be split

up amongst a certain

number of choirs. But

it was left entirely

to the performers to

decide how big each

was to be and how the

vocal and instrumental

parts were to be

assigned. The

contrasting of large

and small choirs or

choirs of the same

size, of soli and

tutti, of voice and

instruments either

together or

separately, of light

and shade, loud and

soft, near and far -

all this produced a

brilliant variety of

sound. There was such

a degree of freedom

that, for example, “in

the event of a lack of

sopranos and a

superfluity of

tenors,” the latter

could take over the

part of the former

(Giovanni Ghizzolo,

1619). The exchanging

of parts was

permitted, and each

choir could be

subdivided - providing

there were enough

partbooks to go round.

Soloists - whether

vocal or instrumental

- could take over one

part and the continuo

instruments would play

the others. In

this recording much

use is made of these

and many other

possibilities.

From 1565 on,

instrumentalists were

a permanent part of

the choir of San Marco.

The development of

independent

instrumental pieces

did not at first mean

that they were

composed in a style

appropriate to the

particular

instruments. Such

works could be played

at will “cum omnis

generis instrumentis.”

In this recording

there are pieces

played by families of

instruments and others

by mixed groups; solo

instruments are set

off one against the

other; strings and

wind are divided;

keyboard instruments

used as an independent

choir. The

fountainhead of

polychoral music was

Venice. Around the

year 1600, numerous

North Italian and

foreign musicians were

studying there.

Heinrich Schütz,

Hans Leo Hassler,

Gregor Aichinger,

Giovanni Battista

Grillo and many others

came “to visit and

listen to that paragon

of all perfect music

and jewel of Italy,

Giovanni Gabrieli”

(Christoph Klemsee,

1613). Before that

date, the personal

friendship between

Andrea Gabrieli and

Orlando Lasso (22

years his junior) had

been the cause of the

Venetian polychoral

style becoming known

north of the Alps; and

after the two

composers had made a

journey together and

Lasso had paid several

visits to Venice, the

composer to the Munich

court adopted the

“Venetian manner"

wholeheartedly.

Hans-Martin

Linde

Translation

by David Potter

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|