|

1 LP -

1C 063-30 106 - (p) 1973

|

|

| 1 CD - 8

26472 2 - (c) 2000 |

|

| 1 CD -

CDM 7 63424 2 - (c) 1990 |

|

Guillaume

de Machaut (um 1300-1377) - Chansons II.

|

|

|

|

|

|

I. Moult sui de

bonne heure nee (Virelais 37)

- Mezzosopran, Laute

|

3' 54" |

|

II. Quant

Theseus, Hercules et Jazon

(Ballade 34) - Mezzosopran,

Altus, Douçaine, Fiedel, Laute

|

7' 07" |

|

| II.

Hoquetus David (Hockett) - Organetto,

Blockflöte, Rebec |

2' 03" |

|

III. Doulz

viaire gracieus (Rondeau 1) -

Altus, Harfe, Laute

|

1' 40" |

|

| IV. Honte,

paour, douptance meffaire

(Ballade 25) - Mezzosopran,

Laute, Fiedel |

5' 51" |

|

| IV.

Honte, paour, douptance meffaire

(Ballade 25) - Laute, Gambe (anonym:

Faenza Nr. 117) |

2' 53" |

|

|

|

|

| V. Fons - tocius

- O livoris (Motet 9) - Mezzosopran,

Altus, Douçaine |

1' 55" |

|

| VI. De toutes

fleurs (Ballade 31) - Altus,

Harfe, Laute, Fiedel |

6' 19"

|

|

| VI. De toutes

fleurs - Guittern, Harfe (anonym:

Faenza Nr. 117) |

2' 22" |

|

VII. Quant en

moy - Amour et biauté parfaite

(Motet 1) - Mezzosopran, Altus,

Lira

|

2' 19" |

|

| VIII. Comment

puet on mieus ses maus dire

(Rondeau 11) - Mezzosopran,

Laute, Fiedel |

3' 55" |

|

IX. Dame je suis

cilz - Fins cuers dousz (Motet

11) - Mezzosopran, Altus, Lira

|

2' 01" |

|

|

|

|

STUDIO DER FRÜHEN

MUSIK / Thomas Binkley, Leitung

|

|

-

Andrea von Ramm, Sängerin,

Harfe, Organetto

|

|

| -

Richard Levitt, Sänger

|

|

-

Sterling Jones, Fiedel, Lira, Rebec

|

|

| -

Thomas Binkley, Laute, Guittern,

Blockflöte,

Douçaine |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bürgerbräu,

München (Germania) - 19-21 giugno

1972 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Gerd

Berg / Johann Nikolaus Matthes

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

EMI

Electrola "Reflexe" - 1C 063-30

109 - (1 lp) - durata 42' 35" -

(p) 1973 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - CDM 7 63424 2 - (1

cd) - durata 42' 35" - (c) 1990 -

ADD |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

EMI

"Classics" - 8 26476 2 - (1 cd) -

durata 42' 35" - (c) 2000 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

GUILLAUME

DE MACHAUT GUILLAUME

DE MACHAUT

"Qui

de sentement ne fait son

dit et chant contrefait."

(He, whose

words and song lack true

feeling, falsifies all.)

The spiritual center in the

life of Guillaume de Machaut

was the city of Reims in the

Champagne. In

the domain of this diocese he

was born, possibly in the

small borough of Machault a

few miles away from Reims.

About 1327

he became a prebendary of the

cathedral of Notre Dame in

Reims and seems to have lived

in this town for the rest of

his life until 1377.

But he undertook long

journeys.

As a young man, he was familiarus

and secretary of Jean de

Luxembourg King of Bohemia. He

accompanied him on his various

trips and campaigns throughout

Europe between 1327 and 1337. We

find him present during the

siege of Znaim in Lithuania in

December 1328. In

January 1329 he was in Königsberg,

visiting Breslau afterwards

and taking part in the

conquest of Poland and Silesia

in March; in May he was at the

king’s court in Prague and in

June already back in Paris

preparing himself for a trip

to the South, to Brescia,

Bergamo, Cremona and Parma.

Later in his life, he retired

from politics, settled and

lived as a singer at Reims on

a prebend, and continued to

work various masters, among

them Jean’s daughter Bonne,

the wife of Jean le Bon of

France. Subsequent to her

death in 1349, he worked

occasionally for Charles II King

of Navarre; for Jean Duc de

Berry and probably also for

Charles V of France. And it

may have been for the

coronation of this king that

he wrote the Mass of Notre

Dame in Reims in 1364.

One of the last benefactors in

his life was Pierre de

Lusignan, King of Cyprus,

between 1361 and 1369, and

through him Machaut travelled

as far as to Alexandria,

possibly also to Cyprus.

It was also towards the end of

his life that he fell in love

with a noblewoman of the

Champagne, Péronne

d'Armentieres. In

1360, he saw her for the first

time when she was not yet 20

years old.

His poem Le Voir Dit,

written between 1362 and 1365,

contains 45 letters exchanged

between them and more than

9000 lines of poetry telling

of their relationship and

containing interesting remarks

on his work and her influence

on him.

"Toutes

mes choses ont été faites

de vostre sentement, et

pour vous especialement."

(All my

works result from your

sentiment and are especially

for you.)

The works

Machaut wrote

an enormous quantily of

poetry; and more music is

preserved by him than by any

other composer of the

fourteenth century. There are

no fewer than six large

manuscripts devoted to his

work, several of them

apparently compiled under his

own direction:

- New

York, Wildenstein

Collection, Vogüé

manuscript, ca.

1369. The earliest and

best manuscript. Very

neatly written and

lavishly illuminated.

- Paris,

Bibliothèque

Nationale, f. fr. 1584.

14th century. Includes

fineilluminations

among which are twoportraits

of G. de Machaut himself.

- Paris,

f. fr.

22545 and 22546.Around the

same date. This doublevolume

includes a more completecollection

of Machaut’s works.

- Paris f. fr.

1585.

Possibly ca. 1400. It seems

to have been copied from No.

1; but is far less

carefullywritten.

- Paris

f. fr. 1586.

ca. 1400.

- Paris,

f. fr. 9221.

ca. 1400. Probably compiled

on commission for theDuc de

Berry. The order of pieces departs

from that of the more central

Machaut manuscripts and many

of the musical details

differ. This

is the most splendid of

the set and

is magnificently

illuminated.

These

manuscripts have been

consulted in the preparation

of two monumental editions of

his music:

- Friedrich

Ludwig, Guillaume

de Machaut,

Musikalische Werke.

Leipzig,

Breitkopf und Härtel.

- Leo

Schrade, Poliphonic

Music 14th Century,

vol. 3. The Works

of Guillaume de

Machaut.

1956

L’Oiseau-Lyre, Monaco.

Some of

the more important longer

poems of Machaut in these

manuscripts include:

- Le

Dit du Vergier (very

early)

- Le Jugement du Roi

de Behaigne (before

1346)

- Le

Jugement du Roi de

Navarre (1349)

- Le

Remède

de Fortune (Maybe as

early as 1342.

It includes music and

describes many of his

lyric forms.)

- Le

Confort d'Ami

1357; sent to the King of

Navarre while in prison)

- La

Fonteinne amoureuse

(ca. 1362)

- Le

Voir Dit (1362-65).

For Péronne

d’Armentières

- La Prise

d'Alexandrie (ca.

1370).

The presumption that

Machaut visited Cyprus in

addition to other

locations in the Autre-mer

is based on this work

- La

Louange des Dames

These works have been edited

at various

times and places - we cite the

standard work: E. Höppfner:

ŒUVRE LITTÉRAIRE

DE GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT

Machaut’s musical works are

normally laid out in the

manuscripts in the following

order, and include:

- 18 Lais, plus 6 without

music

- 1 Complainte and 1 Chanson

Royale

- 24 polyphonic motets

- La Messe de Notre Dame

- Hoquetus David

- 42 polyphonic Ballades

- 22 polyphonic Rondeaux

- 33 Chansons Baladees of

which 25 are monophonic.

Machaut -

Chansons 2

This recording

completes a two-volume

portrait in sound of that

remarkable contemporary of

Chaucer and Petrarch, Guillaume

de Machaut (1300-1377),

which we began with monophonic

works and continue here with

polyphonic works.

Often music is described in

terms of its statistics, the

keys, the cadences, the

imitations, the number of

parts, and so forth. We find

this sterile and misleading,

because it invariably

disguises the important

musical issues.

We would rather draw the

listener’s attention tothe

essential characteristics of

two different worlds of

Machaut’s music, suggesting

the general musical (not

historic) aims and attributes

of each.

In characterizing his

monophonic works, we search

for words and expressions that

refer predominantly to

emotional qualities and

responses rather than to

intellectual content, while

the description of his

polyphonic works requires

terms which stress the

intellectual and formalistic

side of his art (of course,

some of both is present in

almost all music). This

contrast is to be found within

the work of many composers -

consider for example Schönberg’s

Verklärte

Nacht in contrast to his

Variationen für

Orchester.

The first reveals a

concentration on the emotional

meaning while the other places

the emphasis on structural

ordering.

Neither the one nor the other

can claim to be better, or

more advanced, because it is

the demands of a compositional

discipline which govern the

relationship between emotional

and intellectual response.

To focus on this problem in

the music of Machaut requires

an understanding of the

inherent differences between

monophonic and polyphonic

music. Polyphonic music

consists of more than one

composed musical line, which,

taken together, constitute the

piece of music.

Monophonic music has but one

composed musical line, on

which the musicians elaborate

in performance, and for which

an accompaniment frequently is

devised by the players.

Monophonic music is not

completed by the composer but

by the players themselves in

performance.

Polyphonic music is complete

when it leaves the composer’s

pen.

Thus, a player might devise an

accompaniment for a monophonic

chanson

in accordance to the

characteristics of his

favorite instrument, whereas

in the performance of a

polyphonic piece, he will

select the instrument

according to the range and

character of the already

written part. Different

performances of a polyphonic

piece will tend to be somewhat

similar, those of a monophonic

piece, very dissimilar.

The 14th-century composer

controlled the performance of

a polyphonic piece in much the

same way as today a composer

of electronic music works

himself into the performance

by minimizing the creative

contribution of the performer.

The composer, then as now, can

justify this intrusion only by

making the parts and the parts

of parts dependent upon his

own thinking, his own

organization. He can for

example (and Machaut did,

Rondeau 14) write a piece that

is the same played forwards or

backwards (one recalls

organizational features in

Webern’s opus 18 and many

other places), an

intellectualism which never

could come about in the

improvisatory player-dominated

performance of monophonic

music.

Clearly, the composer goes

about his work quite

differently in these two

camps. And so should the

performer. And that is why

have made two records.

The polyphonic music is

carefully constructed, yet

Machaut never fails to be

aware of the emotional aims.

He selects formal structures

not by chance but according to

inherent features of the

structure which - to some

extent through tradition -

designate the underlying

affect of the composition.

Generally speaking, he employs

four forms in polyphonic

compositions: (In the

following diagrams, capital

letter indicates the

repetition of a line of text

with its music, a lower case

letter indicates a new text

line to that music.)

- Virelai.

AbbaAbbaA... This form is

light and simple. It

derives from the

monophonic form and from

danced song. It is never

employed for complicated

and intricate

compositional manoeuvres.

- Rondeau.

ABaAabAB...

This form is complicated,

frequently involving

chromatic experiments and

serious, expressive lines.

It is not light, but it

has moving qualities.

- Ballade.

a a b... Structurally very

simple, having no refrain

line, yet it is a form

employed for the most

complicated intellectualconstructions.

The relationships between

the parts are highly

organized (several are in

four parts).

- Motet

isorhythmic. Whereas

the forms mentioned above

all contain two distinct

musical parts (a and b),

the motet is organized by

the repetition of the

lower part, with free

composed upper parts

overriding these

repetitions. The lowest

part is instrumental

(there is one exception),

and the upper parts

contain a different text

in each part, sung

together. This form gains

in meaning as the subtle

sense of the seeming

disorder becomes clear to

the listener. It is the

shortest structure.

A word must be

brought about the instrumental

pieces in this recording.

There are three, one of which

- the David hocket - is all

Machaut’s, being a singular

composition not unlike the

earlier hockets of French

province which one Italian

early theorist said were

written for flutes.

They constitute an

instrumental equivalent of the

motet. The other two are

arrangements of two of his

ballads preserved in an Italian

manuscript now in the library

of Faenza.

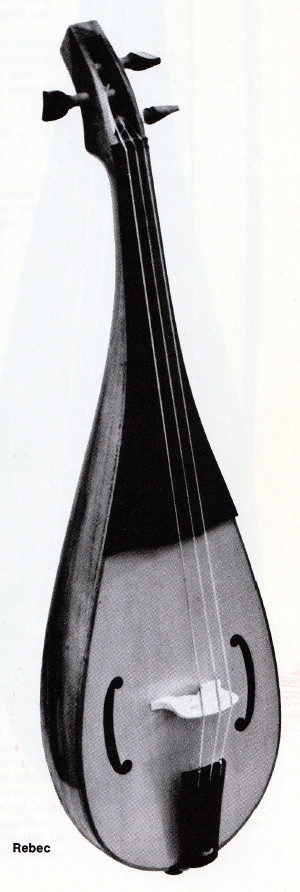

The instruments: Lyra,

lute, vielle, harp.

The lyra,

a small, pear-shaped

instrument with three chords

which was played in a vertical

position. It

has a burdoun chord between

the two melody-chords.

The vielle

is the best-known of

instruments of this time. It

had between three and five

chords and was mainly played

from the shoulder.

The 13th-century lute

is similar to the Arabic ’ud

of our day. Its typically

occidental characteristics

appeared as late as in the

15th century when the neck

grew broader and the distance

between the chords was changed

etc. at which time they began

plucking the instrument with

fingers instead of a plectrum.

The medieval harp was

diatonically tuned and was

provided with between 21 and

26 chords.

Thomas

Binkley

|

|

|

EMI Electrola

"Reflexe"

|

|

|

|