|

|

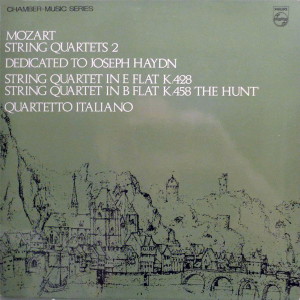

Philips

- 1 LP - 839 605 - (p) 1967

|

|

| Philips

- 1 CD - 422 832-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

six "Haydn" Quartets - 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet (3.) No. 16 in E flat

major, KV 428 |

|

28' 13" |

|

| -

Allegro ma non troppo |

7' 21" |

|

|

-

Andante con moto

|

9' 05" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto |

6' 21" |

|

|

| -

Allegro vivace |

5' 26" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet (4.) No. 17 in B flat

major, KV 458 "The Hunt" |

|

27' 24" |

|

-

Allegro vivace assai

|

8' 47" |

|

|

| -

Moderato |

4' 23" |

|

|

| -

Adagio |

7' 43" |

|

|

| -

Allegro assai |

6' 31" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa

Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli,

viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Théâtre

Vevey, Vevey (Svizzera)

- 14

agosto / 1 settembre 1966 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio

Negri |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 839

605

| 1

LP | (p) 1967

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 422 832-2

| 1

CD - 55' 37" | (c) 1989 | ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The two

quartets on this record

belong to a set of six which

Mozart dedicated to Joseph

Haydn in 1785, and which

must be included among his

finest work. "They are, in

fact, the fruit of long and

laborious toil," says the

composer in his letter of dedication

which is couched in terms

of warm personal

friendship and high

professional regard.

As

far as the string

quartet was concerned

any veneration Mozart

felt for Haydn was quite

understandable. At the

time the letter was

written Haydn had

composed more than 40

quartets which

represented most of the

significant growth of

the form from simple divertimenti

for a fortultous

combination of

instruments without

continuo to the highly

demanding medium of

musical expression we

hear here and which not

much later was to be the

channel of Beethoven's

inspiration.

Alongside

this musical evolution

Mozart himself

developed. In his 13

quartets before the

"Haydn" set we can see

the early influence of

the Italian style

being superseded by

the influence of

Haydn's experiments;

we see the

emancipation of the

viola and cello, which

become increasingly

independent voices

instead of stiff and

servile accompanying

instruments.

But

before his quartets

reached full

maturity, Mozart

himself had to win

artistic

emancipation. The

last quartet before

the "Haydn" set was

written in 1773,

when he was in the

service

of the tyrannical

Archbishop of

Salzburg. But by

the time he began

the set in 1782 he

had broken free of

the court's

shackles, had

married the woman

he loved (against

his father's

wishes), and had

set up home in

Vienna, facing the

world with little

money but with a

brave new spirit

of independence

which helped to

make the boy a man

and the precocious

composer a master

of his art.

Strangely,

and perhaps

significantly,

Mozart's

inactivity in

the field of the

string quartet

between 1773 and

1782 matches

a similar pause

in Haydn's

quartet output

which stopped in

1772 and began again

in 1781. In

that year he

published his

famous

"Russian"

quartets

which, he

announced,

were written

"in an

entirely new

and special

way". They

did, in fact,

display a much

greater degree

of artistic

unity,

particularly

in close

inter-relationship

of their

thematic

material.

There is no

doubt that

Mozart was

considerably

impressed and

influenced by

this new step

forward in

Haydn's work

and this was

probably the

decisive

factor in

encouraging

him to

take up the

form again in

1782 with the

G major

quartet K.

387. In the

six quartets

of the "Haydn"

set we see a

new Mozart - a

Mozart who

looks forward

to Beethoven

rather than

backward to

the Baroque.

We see him

striving for

and achieving

the unity that

Haydn sought

in the

"Russian"

quartets, but

in a

completely

individual

way. In the

set we often

find

Haydnesque

movements but

within their

contexts they

coulf have

been written

only by

Mozart.

Exactly when

Mozart

conceived the

idea of the

dedication to

haydn is not

clear but it

seems likely

that it was

not until the

personal

acquaintance

of the two

composers

(they first

met in 1781)

became a close

friendship in

1784 when

Haydn, then

Prince

Nicholas

Esterhazy's

musical

director, paid

an extended

visit to

Vienna with

the court. On

several

occasions

Mozart was

invited to

play at the

Esterházy

musical

evenings and

soon both

Haydn and he

were taking

delight in

playing

chamber music

privately

together with

mutual friends

- Haydn

playing first

violin and

Mozart the

viola in

quartets. By

the time this

friendship had

fully flowered

three of the

quartets in

the "Haydn"

set had been

written.

In spite of

this the set

as a whole

displays a

wonderful

integration of

style,

technique and

mood and when

it was finally

presented to

Haydn in

1785 he at

once

recognised the

true genius

behind it -

something to

his credit,

for he could

have had

little

opportunity

before then to

assess the

real stature

of the younger

composer.

After a

performance of

three of the

works at

Mozart's home

Haydn drew

aside Leopold

Mozart, the

composer's

father who was

on a visit

from Salzburg

at the time,

and told him

confidentially:

"I declare to

you before God

as an honest

man that your

son is the

greatest

composer I

know either

personally or

by hearsay; he

has taste and,

moreover,

complete

mastery of the

art of

composition."

The

quartets not

only impressed

him as a

listener and

performer;

henceforward

they were to

exert a

noticeable

influence on

his own work -

as they were

to influence

Beethoven when

he came to

carry the

quartet to its

spiritual

zenith.

The

care that the

Quartetto

Italiano have

taken in these

recordings in

going back

wherever

possible to

the original

tempo

indications is

important. The

tendency at

the time the

quartets were

written was

towards an

increase in

pace in the

minuet,

particularly

in the works

of Haydn.

There is

reason to

believe,

however, that

Mozart was

concerned

about this

tendency and

that this was

reflected in

his original

tempo

indications.

Believing that

clarity of

detail and

care in the

expression of

mood and

character rare

of first

importance in

these works

the Quartetto

Italiano have

adhered, for

instance, to

the

"allegretto"

markings of

the first

edition rather

than the

"allegro" of

later editions

in general

use. It was

not a lightly

taken step.

All the

bowings,

tempi, and

dynamic

indications

used in these

performances

have, in fact,

been decided

on only after

the most

careful

research by

the members of

the quartet

themselves

based on the

autograph and

first editions

and other

important

contemporary

documents.

These have

been studied

and carefully

compared with

later sources,

particularly

the Einstein

and Bärenreiter

editions. The

result on

these records

is not so much

a performance

as a dedicated

reappraisal of

Mozart and his

work.

In

many respects

these six

masterpieces

defy analysis.

The following

notes are

intended only

to provide

ssimple

pointers to

the artistic

profundity and

technical

complexity of

these works

and to

encourage the

listener to

give them the

close

attention they

deserve and

can so amply

repay.

A.

David Hogarth

String

quartet in E flat, K. 428

This

quartet composed in 1783

is full of sudden and

surprising flashes of

trepitation, and we get

one almost as soon an

the work has begun. The

cromatic main theme of

the first movement is

immediately stated in

bold uniso, giving a

feeling of tonal

ambiguity after

an initial united

emphasis on the tonic E

flat. But when the theme

reappears a few bars later

it is suddenly richly

harmonised with bold

use of a diminished

seventh chord. A long

trill on the first

violin announces the

arrival of the second

theme which is more

comfortingly melodic.

The development is

dominated by a soaring

passage of triplets

and is followed by one

of Mozart's cleverly

reworked

recapitulations.

Chromaticism

is one of the main

features of the

second movement - so

much so that it has

often been compared

with Wagner's

chromaticism in

"Tristan und

Isolde". Here we see

the master harmonist

at work with the

tension of the

harmony contrasting

perfectly with the

smooth legato

phrasing of the

theme and providing

overall an exquisite

bittersweet quality.

The minuet

(in E flat) is

delightfully fresh

and stimulating

and has a distinct

folk flavour in

its closing

section. This is

intensified in a

mysterious way in

the trio, which

begins strangely

in C minor before

wending its way to

its proper key of

B flat major.

The

robust, vigorous

finale is

Haydnesque in

style but

constructed in a

typical

Mozartian manner

which combines

characteristics

of rondo and

sonata form. For

simplicity's

sake it is

probably casier

to regard it as

a sonata-form

movement without

a development.

There

are two main themes

and a number

of episodes

related to the

business-like

first subject

which returns

in rondo

fashion until

the second

subject

appears in the

dominant with

its enchanting

little triplet

and emphatic

accents. The

"recapitulation"

begins after

an appropriate

pause and

presents all

the material

in cleverly

edited form.

The work ends

with the first

theme

reappearing in

a coda.

String

quartet in B

flat major, K.

458 ("The

Hunt")

This

quartet,

completed on

November 9,

1784, has some

coincidental

links with its

predecessor -

the

persistence in

places of the

folk lavour of

K. 421's

minuet and the

Haydnesque

nature of its

finale. The B

flat major is

probably the

most popular

of the six

"Haydn"

quartets and

has been given

the nickname

"The hunt"

because of the

theme of the

Haydnesque

first

movement,

which suggest

a hunting song

with its

galloping 6/8

rhythm, its

horn-like

phrasing, and

the soft

echoing of its

inner parts.

As usual

Mozart starts

with sonata

form, but this

time it is not

at all regular:

there is no

proper subject

and instead

the

development

begins with

what seems to

be a new theme

(it is, in

fact, a melodie

development)

in the

dominant key

of F major -

the key which

a normal

second subject

would have

had. Another

surprise is

the long coda

which

mischievously

begins almost

like a new

development

when one is

prepared for

the end of the

work at the

codetta in the

recapitulation.

The

second

movement is a

straighrforward

minuet and

trio,

presumably to

separate the

boisterous

good humour of

the first from

the profundity

of the third -

the minuet's

easy grace is,

in fact, the

perfect

emotional

bridge.

The

adagio (in E

flat) is the

real heart of

the work. Its

tender

eloquence is

combined with

latent power

in the harmony

and it has

many movements

of supreme

beauty,

particularly

in the second

theme. Here

the first

violin subtly

evades the key

of B flat on

which the

cello insists

when the theme

first appears

and then the

cello takes

over itself,

playing the

theme on its

golden upper

register.

There is no

development

section the

working-out

being

continuous and

"unofficial".

The

finale in

sonata form

takes us right

back to the

Haydnesque

humour of the

first

movement.

Again the main

theme is

folk-like and

has a "family"

resemblance to

the initial

hunting song.

The second

subject is

more

reflective.

The

development

concentrates

mainly on a

fugato

treatment of

the main

theme's second

phrase but

halfway

through we

come on a

sudden hunhead

passage which

seems to mimic

the entry of

the adagio's

second theme.

Unlike the

first movement

there is no

coda, a few

additional

phrases

sufficing to

bring the work

to an enphatic

close.

|

|

|