|

|

Philips

- 1 LP - 802 806 - (p) 1968

|

|

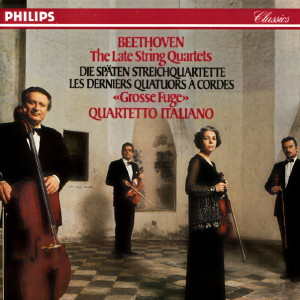

| Philips

- 4 CDs - 426 050-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132 |

|

47' 10" |

|

-

Assai sostenuto - Allegro

|

10' 00" |

|

|

| -

Allegro ma non tanto |

8' 21" |

|

|

-

Canzona di ringraziamento

(Molto adagio) - Sentendo nuova

forza (Andante)

|

19' 33" |

|

|

-

Alla marcia, assai vivace -

Più allegro - Presto

|

2' 20" |

|

|

-

Allegro appassionato

|

6' 55" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli,

viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Théâtre

Vevey, Vevey (Svizzera)

- 18-31

agosto 1967 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio

Negri | Tony

Buczynski |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 802

806

| 1

LP | (p) 1968

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 426 050-2

| 4

CDs - 63' 45" - 62' 00" - 42'

22" - 47' 10" - (4*,

1-5) | (c)

1989 | ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

These was a time

early in the century when

an unfortunate mystique

surrounded the last five

of Beethoven's sixteen

string quartets. They were

regarded as the last

terrible utterances of a

musical superman which

were somehow beyond mortal

comprehension. Ordinary

music lovers baffled by

esoteric discussion of

their spiritual

significance hesitated to

approach this holy ground

and those who had the

temerity to do so somehow

guilty about finding

enjoyment in them ar a

first hearing.

The

last quartets are, in

fact, completely

approachable works

and to say this in no

way detracts from their

greatness - for

greatness does not imply

lack of enjoyment at the

first hearing but rather

increased enjoyment at

the second. The real

measure of these works

is that no matter how

often they are heard,

they still have

something to offer the

listener.

The

truth is that

Beethoven's

greatness lay in his

humanity and not in

some supposed

divinity; his last

quartets are all the

more meaningful if we regard

them for what they

are - great

testaments of

human experience

in which joy and

humour have their

place

with deeper

emotions.

The

A Minor Quartet,

Op. 132 has a

good claim to

being the most

human of them

all. It was the

second (in order

of composition)

of a set of

three

commissioned by

the Russian

Prince Galitsin

in 1823 - a

commission which

encouraged

Beethoven to

devote himself

to the string

quartet form

again after a

gap of nearly

fourteen

years.

Illness,

however,

interrupted

the

composition in

1825 and in so

doing became

the central

feature of the

work. Over the

deeply felt

Adagio,

Beethoven

inscribed

"Hymn of

Gratitude of

one who has

recovered from

illness to the

Deity, in the

Lydian mode" -

the illness

being a

flare-up of

the stomach

and liver

troubles which

bothered him

chronically in

later life and

must have been

all the more

depressing in

the isolation

imposed by his

then total

deafness.

Beethoven's

sketchbooks

show that the

basic material

and form of

the work

emerged from

wide study

which affected

many other

works of the

period. While

working on the

Missa

Solemnis,

for instance,

he became

engrossed in

the early

liturgical

music of the

Roman Catholic

Church and the

works of

Palestrina

which he found

in the library

of the

Austrian

Archduke

Rudolph, for

whom the work

was intended.

These

influences

became marked

in his later

works and

account for

the use of

what he calls

the Lydian

mode in this

quartet. (It

is actually

the Hypolydian

mode the scale

represented by

the white keys

of the piano

between F and

F.)

The

sketchbooks

show, too, an

obsession with

the four top

notes of the

minor scale

and his

experiments

with their

intervals gave

rise to the

quartet's

four-note

opening as

well as the

fugue of the

G-Sharp Minor

Quartet, Op.

131 and the

Grosse Fugue

(originally

the finale of

the B-Flat

minor Quartet,

Op. 130).

There is also

some evidence

that the main

subject of

the A Minor's

finale was at

one point

considered for

the finale of

the Ninth

Symphony.

At

the same time

Beethoven was

advancing his

own frontiers

of form even

further. Form

in the last

quartets, as

in the late

piano sonatas,

had become for

Beethoven a

flexible

channel whose

shape was

determined by

what

had to be

expressed

rather than

the rigid mold

of Haydn and

Mozart to

which the

content had to

conform.

The first

movement of

the A Minor

Quartet, for

instance, is

unique in its

structure and

the Adagio

is a

development of

the

double-variation

form also

employed in

the slow

movement of

the Ninth

Symphony.

But

however

unusual the

forms of these

movements may

be, they are

quite as

clearcut and

straightforward

as the regular

forms (the

scherzo and

trio and the rondo)

which

Beethoven uses

in the quartet

when they suit

his artistic

purpose.

Certainly they

should not

discourage

anyone

approaching

the quartet

for the first

time. The fact

is that,

despite the

lenght of the

work and its

"peculiarities"

- and despite

the esoteric

theories of

music-metaphysicians

of earlier

days -

contemporary

accountes

prove that the

work was very

popular in

Beethoven's

lifetime. The

composer's

nephew

Karl, for

instance, was

present at the

first public

performance on

November 6,

1825. (The

work was first

heard

at a private

recital two

months

before.)

"The

hall was

packed no

capacity,"

Karl wrote to

his uncle.

"It was too

full to hear

many of the

comments,

although I do

remember that

many of the

passages were

greeted with

cheers and

many members

of the

audience could

speak of

nothing else

than the

beauty of the

new quartet

after the

concert was

over.

Schuppanzigh

wishes to play

it again in a

fortnight's

time."

If

the Viennese

public could

show such

unabashed

pleasure in

hearing the

work for the

first time,

there seems

little reason

why we should

feel guilry

about enjoying

our first

encounter with

it, or about

looking

forward to the

even deeper

pleasures that

growing

familiarity

with this

musical

masterpiece can

bring.

First

Movement

This

is sometimes

described as a

movement with

three

expositions

but, far from

it being

adaptation of

sonata form,

it has a quite

definite

structure of

its own. It

opens with

four notes on

the cello

which are used

immediately to

build up what

seems like an

introduction

to the first

theme. They

are, however,

thematic

themselves and

provide the

unifying

element of the

whole

movement. When

the first

theme appears

after a sudden

solo scamper

by the first

violin, they

form the basis

of the

accompaniment

and thereafter

continue to

give the music

the appearance

of breathing

slowly and

steadily even

beneath

violent

activity.

Beethoven

continues with

a natural

development of

his first

theme, moving

to F major

(instead of

the expected

dominant of

sonata form)

for the

transition to

the second

theme. It is a

lyrical

flowing melody

shared by the

violins

against a

rippling

triplat

accompaniment

which

disguises the

fact that the

melody's

ehythm is

derived from

the first

theme and that

the harmony is

based on the

opening

build-up of

the four key

notes.

What

would

correspond to

the

development

section in

sonata form

begins with

the key notes

in canon on

cello and

viola. After

their brief

development in

conjunction

with the first

theme,

Beethoven

moves now to

the dominant

of E minor,

with the key

notes in a

forceful

unison, and

proceeds to

restate his

material in a

revised

version (the

second theme

being in C

major). We

emerge in a

questioning

passage with

the four

instruments

hesitating

together

on the key

notes before

moving into

another

developed

version of the

first theme in

the home key

of A minor;

shortened

versions of

the transition

and the second

theme in turn

(the second

this time in

C, the

relative major).

The long coda

is built on

the key notes

and features

of both

themes.

Second

Movement

In

comparison

nothing could

be more

straightforward

in form than

the nest

movement in A

major, which

is a scherzo

and trio. It

is not,

however, the

kind of bold,

boisterous

scherzo

normally

associated

with

Beethoven: the

music has a

strangely

subdued,

almost weary

air about it.

The scherzo

theme is built

the same way

as the

previous

movement's

main theme -

an opening

three-note

motif played

in unison is

used by the

second violin

as the solo

accompaniment

to the

"melody" which

amounts to

only one short

falling figure

on the first

violin. The

fact that the

whole scherzo

is based on

these two

simple

elements gives

it an

inescapable

air of

austerity. The

trio, a mustte

in A major, is

much lighter

in texture but

thebagpipe

drone

characteristic

of this dance

and lack of

key contrast

perpetuates

initially at

least, the

slightly

depressed air.

Third

Movement

The

heart of the

work is the

Molto adagio,

the "hymn of

Gratutude" in

the Hypolydian

mode (see

introduction).

The hymn is

presented in

five short

sections and

is yet again

dual in

character for

each section

is proceded by

a short

prelude which

later assumes

an independent

thematic role.

Beethoven then

presents a

new, more vigorous

theme in D (Andante)

which he marks

"Feeling new

power" -

obviously

symbolising

the regaining

of strenght

after his

illness. The

hymn then

returns on

the first

violin, the

preludial

sections being

developed into

a continuous

polyphonic

accompaniment

in the other

parts (the

cello

retaining the

octave leaps

from its

accompaniment

of the second

theme). The

second theme

is then

recalled for

similar

variation

treatment.

Finally this wonderfully

conceived

movement ends

with further

variation of

the preludial

music, the

hymn being

ever present

like a cantus

firmus but

moving all the

while

from one

instrument to

another.

Fourth

Movement

In

complete

contrast is

the simple,

rather forlorn

little march

in A major

which follows.

It is in two

short

sections, each

repeated, but

even so hardly

merits the

title

"Movement",

Beethoven,

indeed, seems

to reproach

himself for

it, breaking

off into a

passionate

"recitative"

which carries

us into the

finale without

a break.

Fifth

Movement

The

finale is in a

simple rondo

form

(ABACABA), the

main recurring

theme (A)

being a

yearning waltz

stated

initially the

first violin

against a

restless

accompaniment.

Beethoven

moves to G

major for the

first episode

(B), which

opens with the

first violin

trilling in a

series of

descending

phrases

against an

accompaniment

derived from

the preceding

section. After

the return of

A, episode C

(in fact

developed from

the material

of A and B)

carries the

music to an

emotional

climax full of

biting

sforzandos.

Instead of

introducing a

third new

episode

Beethoven then

recalls a new

version of B

after which

yje main theme

makes its

final official

appearance in

an agitated presto.

We then move

into A major

for the long

coda based on

the material

of thema and

episodes

alike.

|

|

|