|

|

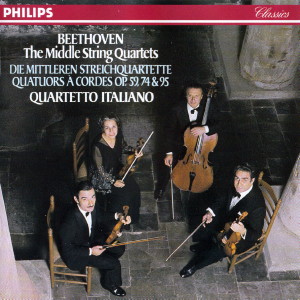

Philips

- 1 LP - 6500 180 - (p) 1971

|

|

| Philips

- 3 CDs - 420 797-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 10 in E flat major,

Op. 74 "Harp" |

|

32' 34" |

|

| -

Poco adagio - Allegro |

10' 16" |

|

|

| -

Adagio ma non troppo |

10' 05" |

|

|

| -

Presto - Pił presto quasi

prestissimo - |

5' 25" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto con variazioni |

6' 48" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| String

Quartet No. 11 in F minor, Op. 95

"Serioso" |

|

20' 22" |

|

-

Allegro con brio

|

4' 19" |

|

|

| -

Allegretto ma non troppo - |

6' 58" |

|

|

-

Allegro assai vivace ma serioso

|

4' 07" |

|

|

| -

Larghetto espressivo - Allegretto

agitato |

4' 58" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli,

viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

La

Salle des Remparts,

La Tour-de-Peilz (Svizzera)

- 20-31

luglio 1971 - (Op. 74)

-

15-27 gennaio 1971 -

(Op. 95) |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Vittorio

Negri | Tony

Buczynski, Ko

Witteveen |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Philips | 6500

180 | 1

LP | (p) 1971

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Philips | 420 797-2

| 3

CDs - 40'

29" - 58' 51" - 64' 35" - (2*,

5-8; 3°, 5-8) | (c)

1989 | ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

L'edizione

in CD contiene anche i

Quartetti Op. 59

nn. 1, 2 e 3.

|

|

|

|

|

Towards the

end of the first decade of

the nineteenth century, a

period that was especially

productive for Beethoven

(including as it did

Symphonies Nos. 2 to 6,

the Piano Concertos Nos. 2

to 5, The Violin Concerto,

the Mass

in C, and "Fidelio"), a

new development set in,

which manifestes itself

particularly in the

Quartets Op. 74 and Op.

95.

Despite

the disparity in their

opus numbers these

works were written

within a year. All the

more surprising then

is the difference in

their characters. The

Quartet in E flat is still

very strongly linked

with the past;

engaging and

unproblematic, it is

a work of beauty and

charm. The Quartet

in F minor, on the

other hand, looks

forward in time,

revealing already

characteristics of

the late quartets;

austere, sober, and

difficult,

compressed and

reduced to

essentials, it

nevertheless

dispalys expressive

power and spiritual

intensity. In both

works one senses a

striving to

relinquish the

pedantic padding of

academic forms, and

a corresponding

masking of key and

the contours of

themes and cadences,

together with the

quest for new tonal

effects.

The Quartet

in E flat, like

the "Emperor"

Piano Concerto,

was completed in

the autumn of

1809, while

Beethoven was

staying at Baden

near Vienna. The

opening of the

first movement is

highly reminiscent

of the celebrated

motif "Muss es

sein?" ("Must it

be?") from the

late Quartet in F,

Op. 135. after a

brief, slow

introduction an

arpeggio theme

leads into the Allegro

proper, clearly

anticipating the pizzicato

passage which

follows

immediately and

recurs repeatedly

in the course of

the movement being

devised obviously

as a special tonal

effect. The

scoring for the

individual

instruments in

alternating half

bars over a range

of up to three

octaves produces a

remarkably

plastic effect,

and from

this the work

acquired its

nickname of

"Harp."

The

second

movement has a

beatiful,

fervent

melody, and in

addition a

chorale-like

accompaniment

with episodic

variations

reminiscent of

the adagios

of the early

symphonies.

What is here

evoked is the

calm before

the storm.

Soon the Presto

of the third

movement, a

furious

scherzo,

bursts upon us

with unrestrained

exuberance. A

second, fugal

section (Pił

presto quasi

prestissimo)

is introduced

fortissimo

by the cello.

The unusual

recapitulation

scheme of

playing the

first section

three times

and the second

section twice

provoked a

query from the

publisher.

Beethoven

insisted on

his

instructions;

he had an

unerring

feeling for

what was

right. As a

result one

enjoys even

the third

repeat of the

first section

as it sweeps

along.

The

variations on

a friendly

allegretto

theme which

form the

finale appear

strikingly

simple in the

context of

Beethoven's

variation

technique,

which even at

that time was

fully mature.

There is no

change of key

or tempo but

simply changes

in the

sequence of forte

and piano

and the

figuration.

If

the Leipzig

"Allgemeine

Musikalische

Zeitung" of

May 22, 1811

could observe

that the

quartet as a

musical form

coult not have

the purpose of

"honouring the

dead or

dipicting the

feelings of

those in

despair, but

should amuse

the mind by

the gentle,

pleasure-giving

play of

phantasy,"

then it is

hardly

surprising

that

Beethoven's

contemporaries

should be

deterred by a

work like the

Quartet in F

minor, Op. 95.

This he knew

well enough.

For six years

he held this

work back from

publication -

a work that

heralded

a new artistic

direction.

The

first bar of

the quartet

contains the

germ of the

complete first

movement, a

passage played

in unison by

all four

instruments.

Within the

space of a few

bars the

fundamentally

sober and

abjective

character of

the whole work

is revealed;

the sudden and

abrupt octave

leaps of the

first violin

in a

march-like

rhythm are

adhered to by

the other

instruments

too. Here

clearly

delineated

themes have

given way to

thematic

material. By

concealing the

distinction

between

melodic and

accompanying

parts the

movement is

typical of

Beethoven's

middle period

- one thinks

emmediately of

the famous

"Appassionata

Sonata."

Contributing

to the

harshness of

sound are

recurrent

stereoyped

accompaniment

figures, for

instance

the

octave-leeaping

semiquaver in

the first

violin. The

tendency to

imply rather

than fully

express

manifests

itself

particularly

in the final

cadences of

the movement:

the cadences

up to

that point

have nothing

of the same

immediacy.

In

a most

original

manner the

second

movement

begins with a

simple

descending

phrase only

four bars

long,

presented

like a

programme by

the solo

cello. The

movement's

individual

character is sustained

by the

Baroque-like fugato,

introduced

later by the

viola, in

which the

polyphonic

interweaving

forms a

striking

contrast to

the

stereotyped

figures of the

first

movement. The

third movement

ought really

to be a

scherzo. And

indeed

scherzo-like

material is

one way or

another

introduced, as

far as the

fundamentally

serious and

occasionally

gloomy mood of

the work

allows. Bu the

movement is

aching and

passionate

instead of

joyous and

gay, in

accordance

with the

marking Allegro

assai vivace

ma serioso.

The strange

trio has a

uniformly

flowing

accompaniment

by the first

violin,

against which

the other

instruments,

in leisurely

fashion, play

episodes like

parts of an

old chorale,

broken up

by intervals

of several

bars in which

only the upper

accompaniment

is heard.

In

the finale, however,

the first

violin

reappears in

its usual

leading role

and in other

respects too

the movement

is highly conventional.

Although at

the first

hearing the

work may seem

rather

forbidding, it

is without

doubt a

significant

step in the

development

toward

Beethoven's

much

misunderstood

late works.

The

period from

wich it dates

marked a

turning-point

in both his

life and

music. In 1809

Vienna

trembled in

the caos

resulting from

the entry of

the French.

Another factor

was

Beethoven's

personal

destiny ("the

daemon in my

ears") which

he lamented to

his friend

Wegeler in a

letter of May

2, 1810: "Oh

life is so

beautiful, but

for me it is

for ever

poisoned." And

Therese

Malfatti is

said to have

turned down at

this tima a

proposal of

marriage from

him. His

statement in aletter

to Therese. "I

am living a

very lonely, quiet

life," surely

finds its

musical

expression in

the intensely

introverted Op.

95.

A

perceptible

inclination to

polyphonic

style is quite

certainly

connected in

some way with

his

contrapuntal

studies for

tuition of the

Archduke

Rudolph at

that time.

Finally,

changed

cirmustances

affecting his

material

standard of

living ought

not to be

understimated.

An annual

salary

guaranteed for

life by three

princes

relieved

Beethoven of

the need "to

write for

bread," while

at the same

time providing

him with a

clear path to

new goals.

Dr.

Hans Schmidt

|

|

|