|

|

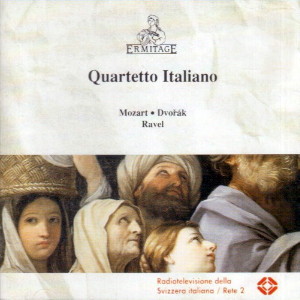

Ermitage

- 1 CD - ERM 117 - (c) 1991

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(1756-1791) |

|

|

|

| Quartetto

in re minore, KV 421 |

|

23' 55" |

|

| -

Allegro |

5' 13" |

|

|

| -

Andante |

5' 10" |

|

|

| -

Minuetto: Allegro |

3' 59" |

|

|

-

Allegro ma non troppo

|

9' 33" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonín Dvořák

(1841-1904) |

|

|

|

| Quartetto

in fa maggiore, Op. 96 "Americano" |

|

24' 01" |

|

-

Allegro

|

6' 49" |

|

|

| -

Lento |

8' 14" |

|

|

| -

Molto vivace |

3' 45" |

|

|

-

Finale: Vivace ma non troppo

|

5' 13" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Maurice Ravel

(1875-1937) |

|

|

|

| Quartetto

in fa maggiore |

|

28' 29" |

|

-

Modéré - Très doux

|

8' 17" |

|

|

-

Assez vif - Très rythmé

|

6' 23" |

|

|

-

Très lent

|

8' 34" |

|

|

| -

Agité |

5' 15" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUARTETTO

ITALIANO

- Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi, violino

- Piero Farulli, viola

- Franco Rossi, violoncello |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione |

|

Collegio Papio,

Ascona (Svizzera) - 10

settembre 1968

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

live |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Radiotelevisione

della Svizzera Italiana/Rete 2 |

Lucien Rosset | Jochen

Gottschall | Alberto Spano

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

-

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Ermitage | ERM 117 | 1 CD

- 76' 37" | (c) 1991 | ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Cover: Guido

Reni (1575-1642) "Il trionfo

di Giobbe". Parigi, Notre

Dame.

|

|

|

|

|

COUNTRY

MUSIC AND

ARCADIA

In

choosing their approach

to Ravel, the Trio di

Trieste and the

Quartetto Italiano

indirectly followed

the teachings of Alfredo

Casella, Ravel’s

long-time friend and

partner in the world

premiere of the

two-piano version of La

Valse, and of

Victor de Sabata,

conductor of

the world premiere of L’enfant

et les sortiléges

and celebrated

interpreter

of Bolero. The

two Italian ensembles

based the reading of all

of their repertoire on

the timbric finesse of

Ravel, on the reliance

of sound as supporting

structure. For the

Quartetto Italiano, the

Bagatelles of

Webern and the Grosse

Fugue of

Beethoven were also

determinant influences,

but they never forsook

their initial grounding

in Ravel, even when the

compass pointed toward a

more direct experience

with Viennese culture.

The Italian instrumental

groups that quickly

gained international

fame were formed in

a period of national

isolation: the campaign

to colonize Ethiopia,

the alliance with

Germany, and then the

war, had limited the

presence of

international ensembles

in Italy,

and had at first made

difficult, and then

blocked, foreign travel

by young musicians.

Paradoxically, this

isolation turned into

opportunity and

advantage, because

within these narrowed

horizons and reduced

stimuli lay the age-old

rapport with French

culture, and Ravel. To

my mind, this situation

allowed, practically

forced, the Quartetto

Italiano and the Trio di

Trieste to work out a

cultural point of view

based on a re-thinking

and an in-depth study of

Italian tradition,

without the direct

imitation and eclectic

diversion that would

have made their

maturation much slower.

They even played from

memory, these young

musicians of the Trio di

Trieste and the

Quartetto Italiano, but

this was far from being

a sign of ostentatious

exhibitionism: rather,

it was a sign of their

unrelenting work to

master a repertoire that

was for all practical

purposes foreign, and

that had no cultural

equivalent in Italy. So,

with Rossini, Donizetti,

Bellini, Verdi, and

Puccini behind them, but

without a Haydn, a

Beethoven, a Schumann,

or a Brahms, the Trio di

Trieste and the

Quartetto Italiano

performed the miracle of

proposing, and having

the world accept, an

interpretive style that

was born in

the Italian

cultural provinces

without appearing

provincial.

I haven’t mentioned

Mozart, because here

there could have been a

direct rapport via the

Italian texts of his

operas. Mozart’s

operas, on the whole,

weren’t exactly popular

in the Italy

of 1935-1945. But at

least Don Giovanni

represented a myth and,

hearing the Quartetto

Italiano perform the

Quartet in d minor K.

421, one can’t help but

notice sublimation of

the theater -

especially in the

unexpected D major

conclusion, heartrending

rather than consoling.

The Quartetto Italiano

thus found, in the

covert presence of

Mozart and in the overt

cultural presence of

Ravel, secure reference

points on a perilous

voyage to all of

the world’s cultural

ports. So the excellence

of their Mozart and

Ravel in the Lugano

concert shouldn’t really

cause us to marvel. But

that strange marriage of

old Bohemia and young

New World that is Dvorak’s

Quartet op. 96 does

require comment.

When playing Dvorak`s

Quartet with "natural"

musicality, one

inevitably falls into

nationalistic sentimentality.

The Quartetto Italiano

knows that this

nationalistic aesthetic

is there in the Dvorak

Quartet, and doesn’t

dismiss it: just listen

to how the sound of the

finale's

second theme recalls a

homespun

violin-accordion duet,

or how the third theme

recalls a country church

organ. Above and beyond

some anecdotal details,

which add "local color"

and which are neither

eliminated nor glossed

over, the Quartetto

Italiano bases its

interpretation on

timbric polyphony,

passing from a

perspective ordering of

musical events to a

simultaneity of

different events which co-exist,

not by virtue of a

hierarchic order, but by

pre-established harmony.

It is no longer a

quartet, but a

conversation in Arcadia,

in which even the most

humble voice arouses

interest and is treated

with loving respect.

From country music to

Arcadia... Dvorak’s

dream at the end of the

19th century, and our’s

at the end of the 20th,

for it seems that each

century’s end gives

voice to impossible

dreams.

Piero

Rattalino

(Translated

from Italian by

Eric Siegel)

|

|

|