|

|

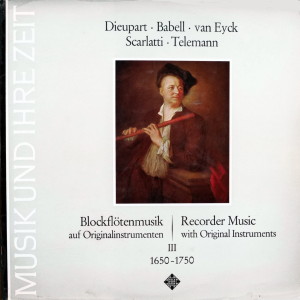

1 LP -

SAWT 9582-A - (p) 1972

|

|

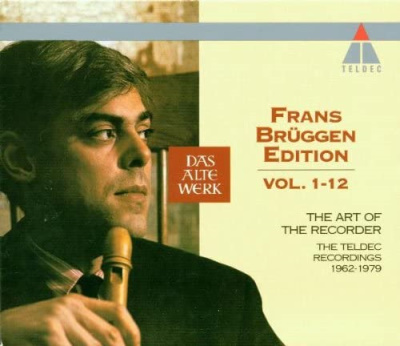

| 12 CDs -

4509-97475-2 - (c) 1995 |

|

| BLOCKFLÖTENMUSIK

AUF ORIGINALINSTRUMENTEN (III) -

1650-1750 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Francis

[Charles] DIEUPART (d.1740) |

Suite

A-dur für Blockflöte und Basso continuo |

(1) |

|

17' 38" |

A1 |

|

- Ouvertüre |

|

5' 20" |

|

|

|

- Allemande |

|

4' 17" |

|

|

|

- Courante |

|

1' 34" |

|

|

|

- Sarabande |

|

2' 18" |

|

|

|

- Gavotte |

|

1' 04" |

|

|

|

- Menuett |

|

1' 45" |

|

|

|

- Gigue |

|

1' 20" |

|

|

| William BABELL (um 1690-1723) |

Concerto

à 7, D-dur für Blockflöte, Streicher und

Basso continuo *

|

(2) |

|

9' 14" |

A2

|

|

- Allegro |

|

2' 41" |

|

|

|

- Adagio |

|

1' 48" |

|

|

|

- Allegro |

|

4' 45" |

|

|

| Jacob Jan van EYCK (um 1590-1657) |

Engels

Nachtegaeltje, Blockflöte solo |

(3) |

|

5' 40" |

B1 |

| Alessandro SCARLATTI

(1660-1725)

|

Sonate

a-moll für Blockflöte, 2 Violinen und

Basso continuo (Orgel) |

(4) |

|

11' 38" |

B2 |

|

-

Allegro |

|

2' 33" |

|

|

|

-

Largo |

|

2' 00" |

|

|

|

-

Fuga |

|

2' 50" |

|

|

|

-

Largo

|

|

2' 00" |

|

|

|

-

Allegro |

|

2' 15" |

|

|

| Georg Philipp

TELEMANN (1681-1767) |

Fantasie

B-dur, Blockflöte solo, TWV 40:12

|

(5) |

|

3' 47" |

B3 |

|

- Allegro · Adagio. Vivace

|

|

2' 42" |

|

|

|

- Allegro |

|

1' 05" |

|

|

|

Fantasie

g-moll, Blockflöte solo, TWV 40:9

|

(5) |

|

4' 38" |

B4 |

|

- Largo |

|

2' 13" |

|

|

|

- Spirituoso |

|

1' 02" |

|

|

|

- Allegro |

|

1' 23" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frans

BRÜGGEN, Blockflöten

Anner BYLSMA, Barockcello

Gustav LEONHARDT, Cembalo und

Orgel

Marie Leonhardt, Violine

Alda Stuurop, Violine *

Antoinette van den Hombergh, Violine

Lucy van Dael, Violine *

Fred Nijenhuis, Kontrabaß

|

Blockflöten:

- (1) = Blockflöte in d'

(voice flute) von P. J. Bressan, London,

ca. 1720 (Sammlung Frans Brüggen)

- (2) = Blockflöte in d'' (sixth flute)

von Thomas Stanesby jr., London, ca.

1730 (Sammlung Edgar Hunt)

- (3) = Sopran-Blockflöte

c'' von Richard Haka, Amsterdam, ca.

1685 (Sammlung Frans Brüggen)

- (4) = Blockflöte

f' von J. B. Gahn, Süddeutschland (?) um

1700; hohe Kirchenstimmung (Sammlung

Frans Brüggen)

- (5) = Alt-Blockflöte

f' von Thomas Stanesby, London, um 1700

(Sammlung Comtesse de la Chambure,

Paris)

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde Kerk,

Amsterdam (Holland) -

Gennaio/Novembre 1971

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9582-A | 1 LP -

durata 52' 35" | (p) 1972 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 6019 | 4509-97475-2 | 12

CDs | (c) 1995 | ADD

- Teldec

Classics "Frans Brüggen

Edition" - Vol. 6 |

4509-97468-2 | 1 CD -

durata 47' 52" | (c) 1995

| (Dieupart)

- Teldec

Classics "Frans Brüggen

Edition" - Vol. 4 |

4509-97466-2 | 1 CD -

durata 58' 32" | (c) 1995

| (van Eyck)

- Teldec

Classics "Frans Brüggen

Edition" - Vol. 3 |

4509-97465-2 | 1 CD -

durata 64' 20" | (c) 1995

| (Babell)

- Teldec

Classics "Frans Brüggen

Edition" - Vol. 1 |

4509-97688-2 | 1 CD -

durata 74' 44" | (c) 1995

| (Telemann)

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

"Der Flötenspieler",

Gemälde von Alexis Grimoux

(1678-1733).

|

|

|

Note |

|

Non esiste, tale e

quale, una ripubblicazione in

Compact Disc di questa

registrazione. I singoli brani

sono però disseminati in diversi

volumi che compongono la "Frans

Brüggen Edition" che è composta da

12 Compact Disc..

Circa la Sonate a-moll di

Alessandro Scarlatti non si

è a conoscenza di un suo

riversamento in Compact Disc.

|

|

|

|

|

The golden age

of the baroque flute occurs

more or less in the epoch of

late baroque, between 1650

and 1750. During these

decades a wealth of solo

music was composed in Italy,

Germany and England. At the

end of the 17th century

instrument makers quickly

adapted themselves to the

new soloist functional

purpose; the flute was given

a much wider range, and its

tone became stronger,

lighter and more versatile

in the higher notes. The

present recording vividly

illustrates how, despite the

narrower fixed rythms and

conical drilling now

introduced everywhere,

flutes still turned out to

be greatly varied in tone

character.

Around 1700 Francis

[Charles] Dieupart

left France to live in

England; he settled down in

London, where he is said to

have died in 1740. In 1705

Dieupart published six

suites for harpsichord, of

which J. S. Bach copied two

(in addition to the table of

grace notes). It was even

asssumed that Bach based his

»English Suites« on them -

they have one theme in

common. In the same year

Dieupart published a

collection of harpsichord

suites in a version for

violin, flute or recorder

with basso continuo, giving

directions for each suite as

to the type of recorder on

which it should be played:

Nos. 1-4 on the »Flûte de

voix« (d recorder), Nos. 5

and 6 on the »Flûte du

quatre« (b-flat recorder).

But even without reference

to Bach, Dieupart’s suites

are worthy of consideration;

they are excellent examples

of French chamber music.

The English harpsichord

player, organist and

violinist William Babell

saw the light of day about

1690. He first learned the

musician’s craft from his

father, a respected

bassoonist, and afterwards

with Johann Christoph

Pepusch. His »compositions«

are for the greater part

harpsichord arrangements of

popular contemporary opera

arias, but at the same time

are also valuable sources of

the embellishment and

improvisation practice, for

instance of Handelian

operas. Babell’s own works,

however, display, especially

in his solo cantatas for

violin (oboe) and

harpsichord, and in

particular the present

»Concerto à 7«, an

astoundingly high standard

of composing subtlety in the

creation of chamber music.

Babell died in 1723 in

Canonbury.

It was during the early

baroque era that recorder

solos were composed by the

otherwise little known Jan

Jacob van Eyck, a

blind recorder and carillion

player, organist and

flautist, who entertained

visitors at the churchyard

with his flute playing. He

was born about 1590 in

Utrecht and died there in

1657. In the middle of the

17th century he published

the »Fluyten Lust-Hof«, a

book containing a large

number of contemporary

popular melodies with

variations for the soprano

recorder. The art of

improvising such

»diminutions« was part of

the style of the times; van

Eyck most likely also played

in this manner the »Engels

Nachtegaeltje« at the

churchyard.

Among the »most diligent«

and keen composer-musicians

of the 17th century are

undoubtedly Alessandro

Scarlatti (1660-1725)

and Georg Philipp

Telemann (1681-1767).

Among his immense operatic

and cantata creations,

Scarlatti’s Sonata in

A-minor shines forth as one

of the few pearls of chamber

music. Telemann on the other

hand devoted almost equal

attention to all types of

composition. His 12

fantasias for solo flute

(1732/33) find their

counterparts in the

collections of unaccompanied

fantasias for violin, viola

da gamba and piano,

published between 1732 and

1735. Telemann gives his

fantasias a loosely jointed,

formal framework, seemingly

improvised with a light

touch.

This recording unites the

Fantasias B-flat major and

G-minor for the alto

recorder, transposed a minor

third higher in accordance

with the custom of the 18th

century. Telemann was

conversant with all

contemporary musical

instruments; this explains

his craftsmanship mastery

which, together with his

eternally fresh talent for

invention, created the

richest treasury of chamber

music of the 18th century.

Recorders in Collections

Usually, a music-lover

looking at any collection of

old musical instruments is

first impressed by the

display of magnificent

harpsichords, by the richly

ornamented lutes and

theorboes and by strangely

shaped instruments like the

serpent. Or, if he happens

to be more technically

orientated, he may be

attracted by interesting

specimens of the transverse

flute that shows its

development from a one-keyed

instrument to the perfected

mechanism of a Böhm flute.

In contrast, it is seldom

that the simple recorder

ever draws much attention to

itself. On account of the

small ammount of space that

the treble and alto

recorders take up, they are

usually designated -

depending on the attitude of

the museum curator - a mere

modest corner of a

show-case, or, in some

instances, withdrawn from

public view altogether and

kept in the store-room.

Furthermore, old recorders

would seem to offer little

that is »novel« to the

ordinary visitor. A certain

ammount of sensitive

penetration of the subject

is requiered before one can

fully appreciate the

numerous delightful

variations in their

construction, decoration and

the material used.

Closer study of the various

collections of recorders in

museums will reveal, in

addition, that there are

relatively few historical

instruments still in

existence. The largest

collection of flutes and

recorders in the world, the

»Dayton C. Miller Flute

Collection« in the Library

of Congress in Washington,

which has about 1600

specimens of the most varied

types and periods, possesses

only about 25 recorders from

the 18th century and merely

one alto and one bass

recorder from the 17th

century.

A large set of Renaissance

recorders (end of 16th,

beginning of 17th centuries)

such as the one to be found

in the Collection of Old

Musical Instruments in

Vienna is therefore of

extreme rarity; and, in this

context, the recorder dating

from about 1450 which was

dug up in Holland and now to

be found in the

Gemeentemuseum at the Hague

seems almost »prehistoric«.

It is a generally known fact

that recorders used to be

constructed in a variety of

sizes and pitches. For

example, we know of the very

rare great-bass recorder,

260 cms in length, and, as

an extreme contrast, the

sopranino, 25 cms in length.

In the first half of the

18th century, when the

recorder experienced its

hey-day and was elevated to

the ranks of solo

instrument, it was the

treble and alto recorder

that enjoyed the most

popularity. It is therefore

understandable that far more

of these two particular

types of recorder have

survived than of the tenor

and bass types.

After 1770 the recorder

gradually disappeared from

the musical scene. An

incalculable number of

valuable pieces must have

been destroyed during the

19th century. Hardly any

more recorders were made.

With the revival of recorder

making 50 years ago

instruments were produced

which were geared primarily

to modern musical practice.

Accordingly, new models were

constructed which were far

removed from their original

counterparts. The historical

instruments that had been

preserved consequently

remained museum pieces; a

fact which was universally

accepted. Museum curators

and private collectors could

(and perhaps preferred to)

do no more than merely take

care of their valuable

specimens to the best of

their ability.

The situation changed

fundamentally when, after

World War II, performing

practice began to follow

along new lines. An

ever-increasing number of

musicians was going in

search of the »authentic«

sound of old instruments.

From then on, collections of

historical instruments were

no longer examined from the

purely aesthetic and

organological point of view,

but from the aspect of

sound. Musicians and

ensembles became engrossed

in problems concerning the

special ways of playing

Baroque instruments, while

instrument-makers strove to

reproduce copies as

accurately true to the

originals as possible. A new

world of sound opened up.

The growing demand for

authentic Baroque

instruments can never be met

by the existing number of

originals. It will be

increasingly necessary,

therefore, to help out with

good copies. Collectors and

museums have to be aware of

the fact that the historic

instruments in their care

are irreplaceable. They are

duty bound to face the

difficult task of finding a

golden mean between the

preservation and propagation

of these instruments.

For curators or collectors a

recording such as this is an

invaluable aid in carrying

out the above-mentioned

task. May it also provide

for the music-lover an

equally valuable opportunity

to penetrate more deeply

into the sound and the world

of Baroque recorder music.

Dr.

Clemens von Gleich

|

|

|

|