|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9577-B - (p) 1971

|

|

| 35 CDs -

0190296467714 - (c) 2022 |

|

| MADRIGALI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Claudio

MONTEVERDI (1567-1643) |

Combattimento

di Tancredi et Clorinda (Torquato

Tasso) - für

Sopran, Tenor, Bariton, 2 Violinen, Viola

und Basso continuo, SV 153

|

Libro

VIII

|

(1) |

|

20' 50" |

A1 |

|

-

Tancredi, che Clorinda un uomo stima - (Testo,

Clorinda, Tancredi)

|

|

|

2' 36" |

|

|

|

-

Sinfonia - Notte, che nel profondo oscuro

seno - (Testo) |

|

|

3' 00" |

|

|

|

- Non

schivar, non parar - (Testo) |

|

|

2' 29" |

|

|

|

- E

stanco e anelante - (Testo) |

|

|

2' 29" |

|

|

|

-

Cos´tacendo e rimirando - (Testo,

Clorinda, Tancredi) |

|

|

2' 16" |

|

|

|

-

Guerra - Torna l'ira ne' cori - (Testo) |

|

|

0' 43" |

|

|

|

- Ma

ecco ormai - (Testo) |

|

|

2' 31" |

|

|

|

-

Amico, hai vinto - (Clorinda) |

|

|

1' 19" |

|

|

|

- In

queste voci languide - (Testo,

Clorinda) |

|

|

3' 43" |

|

|

|

Interrotte speranze - für 2

Tnöre und Continuo, SV 132 |

Libro

VII

|

(2) |

|

3' 10" |

B1 |

|

Eccomi

pronta ai baci - für 2 Tenöre, Baß

und continuo, SV 135 |

Libro

VII

|

(3) |

|

2' 07" |

B2 |

|

Tempro

la cetra - für Tenor, 2 Violinen, 2

Violen und Continuo, SV 117 |

Libro

VII

|

(4) |

|

7' 28" |

B3 |

|

Tu

dormi - für Sopran, 2 Tenöre, Baß

und Continuo, SV 137

|

Libro

VII

|

(5) |

|

3' 15" |

B4 |

|

Lamento

della Ninfa - für Sopran, 2 Tenöre,

Baß und Continuo, SV 163

|

Libro

VIII

|

(6) |

|

5' 22" |

B5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nelly

van der Spek, Sopran

(1 [Clorinda],5,6)

Nigel Rogers, Tenor (1

[Tancredi],2,3,4,5,6)

Max van Egmond, Baritone (1

[Testo],6)

Marius van Altena, Tenor

(2,3,5,6)

Dmitri Nabokov, Bass (3,5)

|

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

(auf Originalinstrumenten)

Gustav Leonhardt, Cembalo und

Leitung

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Westzaan (Holland) -

2/11 Novembre 1970

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

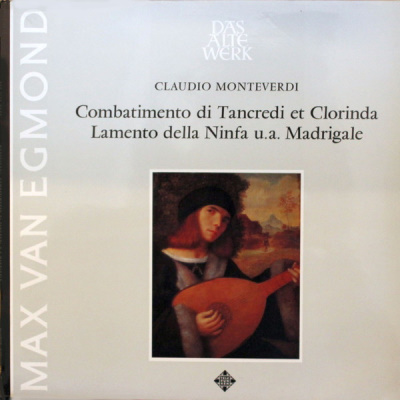

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9577-B | 1 LP -

durata 40' 12" | (p) 1971 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics

"The New Gustav Leonhardt

Edition" | 01902964467714 | 35

CDs - CD 26 - durata 67' 17" |

(c) 2022 | ADD

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

"Der Lautenspieler",

Gemälde von Giovanni Cariani.

Musée des Beaux-arts. Strasbourg.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

In the 16th

and early 17th century

particularly in Italy and

then in England, the

madrigal was the most

important musical form,

music being an integral part

of contemporary court life.

At the same time, the extent

of its popularity and its

lack of restrictive link

with liturgical convention

made it an important vehicle

for experimental composition

and new ideas. Claudio

Monteverdi, admiringly

called by his contemporaries

»oracolo della musica«,

exerted a decisive influence

on the whole course of

musical history. A

»conservative

revolutionary«, like all

great revolutionaries,

gradually he brought about a

change in European musical

style during a long

continual process, a process

of change particularly well

demonstrated in his madrigal

works. Monteverdi occupied

himself with the madrigal

well nigh all his life: in

1587, when he was twenty, he

published his first book of

madrigals, five years before

his death his eighth book

was published.

In his Fifth Book of

Madrigals (1605) Monteverdi

introduced the use of an

accompanying basso continuo.

In defending this innovation

in his preface to the book,

against the attacks of

critical protagonists of

pure counterpoint, he made

this now famous statement:

»l’oratione sia padrona del

armonia e non serva« (»The

text should be the master,

not the servant of music«).

Fully aware of its modernity

he named his new way of

writing Seconda pratticca

(»second way«), as opposed

to the older Prima prattica

(«first way«) - the school

of strict counterpoint. Two

years later, in 1607, he

composed his first dramatic

work, »Orfeo«. Through the

great variety of forms it

contains, both structurally

and musically this work

surpasses anything

previously written in the

older declamatory style of

the Florentine Camerata, and

obviously owes much to the

preceding work done in his

madrigals. In his Sixth Book

of Madrigals (1614),

Monteverdi for the first

time abandoned the

traditional five-part

structure of the madrigal,

trying out various settings,

sometimes in a

soloistic-virtuoso style

(stile concertato).

The Madrigal Book VII and

VIII are of particular value

because they disclose the

pattern of development of

Monteverdi’s dramatic style.

Unfortunately, through a

turn of fate, of the other

numerous dramatic works

written between »Orfeo« and

the two late Venetian operas

»Il ritorno d’Ulisse in

patria« (1641) and

»L’Incoronazione di Poppea«

(1642) little is now extant.

The Seventh Madrigal Book of

1619, entitled »Concerto«,

comprises a tremendous

variety of formal

construction and settings

(1-6 vocal parts and basso

continuo; in addition

frequent use of obbligato

instruments). Thus, in

Tempro la cetra, the first

piece in the collection, the

words of which might well

serve as a motto for the

whole book (»it is only of

love that the lyre can

sing«), the four sections of

the sonnet are composed as

variations over a strophic

bass - itself varied - which

alternate with instrumental

ritornels, a construction

strongly reminiscent of the

famous »Underworld« aria in

»Orfeo« - »Possente spirto«.

The long stretches of

parallel declamation in

»Interrotte speranze«, on

the other hand, are more

reminiscent of the older

style of Florentine opera.

Tu dormi is a four-part work

with both imitative,

polyphonic elements and

chordal passages.

The Eighth Book of Madrigals

appeared in 1638, during the

Thirty Years’ War, under the

title of »Madrigale

guerrieri, et amorosi / con

alcuni opusculi in genere

rappresentativo, che saranno

per brevi Episodii fra i

canti senza gesto« and

dedicated to Emperor

Ferdinand III. By »canti

senza gesto« are meant the

»non-dramatic« madrigals of

the collection. Of the

pieces composed »in genere

rappresentativo« (»in

dramatic style«) should be

mentioned the »Ballo delle

Ingrate« and particularly

the »Combatimento di

Tancredi et Clorinda«. The

»Combatimento« is the

setting of a piece of

Torquato Tasso’s epic poem »

Gerusalemme liberata«

(verses from Canto XII). Its

completely unschematic

construction fits it into no

particular musical category,

though it is sometimes

called a »scenic madrigal«

or »scenic cantata«, and it

has not established any new

form in itself. It is,

however, one of Monteverdi’s

most famous works and has,

through its subtle

musical-pictorial setting of

the words and dramatic

effects, retained its

ability to achieve an

immediate impact even today.

To his Eighth Book of

Madrigals Monteverdi added a

lengthy introduction in

which he clearly defines his

position regarding the works

published (cf. extract from

this in the supplement).

Wolfgang

Dömling

Extract

from Monteverdi’s

introduction to his

Madrigal Book VIII

“...

Having duely pondered upon

the fact that, according to

all the notable

philosophers, the quick

pyrrhic verse metre was used

for all warlike and

powerfully excited dances

and that the slow spondeic

metre was used for the

opposite, I began to realise

that a semibreve sounded

once, was the equivalent of

one spondeic beat, but,

however, if it were to be

divided up into 16

semiquavers, rapidly sounded

one after the other in

connection with a text

dealing with wrath and

indignation, it would

produce something very near

to what I have been trying

to find, even though the

text would not be able to

keep up with the rapidity

achieved by an instrument.

In order to put these

experimental ideas into

practice I turned to the

works of the divine Tasso,

who with such great

originality and simplicity

can so well express any

emotion he chooses. I found

in his description of the

combat between Tancred and

Clorinda an ideal vehicle

for expressing my musical

intentions: for here were

war, entreaties, and even

death to be interpreted in

music. In 1624 I had the

composition performed in the

house of my most illustrious

patron and special master,

the honourable Girolamo

Mozzenigo, most excellent

dignitary of our nable

republic. The music was

performed in the presence of

the Venetian nobility and

was received with much

applause and praise ... I am

anxious that it should be

known that the first

experiments with these new

means of expression, so

necessary to the art of

music as a whole, were done

by me. Without these means

music was an imperfect

art-form, for only the

gentle and the moderate

could be expressed. At

first, the

musicians—especially those

who played the basso

continuo part—regarded the

playing of a string 16 times

in one bar as highly

ridiculous, hence they only

played the note once per

bar, consequently producing

a spondeic metre instead of

the desired pyrrhic one and

thus destroyed the whole

attempt at imitating the

agitated content of the

text. Attention should

therefore be given that the

basso continuo be played

exactly in the manner

prescribed at all times, and

that all other instructions

as to methods of performance

be strictly followed... .”

|

|

|

|