|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9576-B - (p) 1971

|

|

| 2 CDs -

3984-21760-2 - (c) 1998 |

|

| CONSORTMUSIK

AUF ORIGINALINSTRUMENTEN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| John DOWLAND (1562-1626) |

Pavan

in C - 4-stimmig |

|

|

5' 04" |

A1 |

| William LAWES (1602-1645) |

Suite

Nr. 1 in C - 6-stimmig |

*

|

|

12' 29" |

A2 |

|

-

Fantasia

|

|

4' 59" |

|

|

|

- In

Nomine |

|

4' 09" |

|

|

|

- Air

|

|

3' 28" |

|

|

| John COOPER [Giovanni

Coperario] (1575-1626) |

Fantasia

- 5-stimmig |

|

|

3' 10" |

A3

|

|

Suite

- 3-stimmig |

|

|

6' 35" |

B1 |

|

-

Fantasia |

|

3' 01" |

|

|

|

-

Alman |

|

1' 44" |

|

|

|

-

Galliard

|

|

1' 53" |

|

|

| Thomas SIMPSON (geb. c.1582) |

Ricercar

"Bonny sweet Robin" (1621) -

4-stimmig |

|

|

3' 09" |

B2 |

| Henry PURCELL (1659-1695) |

Triosonate

VI in g |

|

|

7' 55" |

B3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

(auf Originalinstrumenten)

- Marie Leonhardt, Barockvioline

(Jacob Stainer, 1676)

- Antoinette van den Hombergh, Barockvioline

(Michele Platner, Rom ca. 1740)

- Wim ten Have, Barockviola (Joseph

Hill, London 1770)

- Wiel Peeters, Barockviola (Johannes

Tononi, 16. Jahrhundert)

- Dijck Koster, Barockvioloncello

(Giovanni Battista [II] Guadagnini,

1749)

- Anner Bylsma, Barockvioloncello

(M. Gofrilleri, Venezia 1699)

Gustav LEONHARDT, Cembalo und

Leitung (Rainer Schütze, Heidelberg 1963,

nach niederländischem Modell, um 1700)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Westzaan (Holland) -

Novembre 1970

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9576-B | 1 LP -

durata 38' 22" | (p) 1971 | ANA

|

|

|

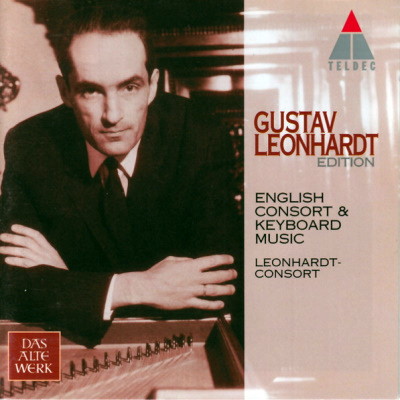

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics

"Gustav Leonhardt Edition" | LC

6019 | 3984-21760-2 | 2 CDs -

durata 70' 20" 57' 02" |

(c) 1998 | ADD

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

"Musikalische

Unterhaltung am Tische"

(Ausschnitt), Gemälde von Johann

Heinrich Schönfeldt (1609 Biberach

- 1675 Augsburg). Gemäldegalerie

Dresden.

|

|

|

Note |

|

Non si è a conoscenza

della ripubblicazione in Compact

Disc della Triosonate VI in g

di Henry Purcell.

|

|

|

|

|

It is often

asserted in Europe, with

characteristic Continental

superiority, that the

British are an unmusical

nation, whose composers - in

comparison to those on the

mainland - have never

succeeded in climbing out of

a state of creative

turpitude. On closer

scrutiny, however, quite a

different picture offers

itself: the famous 13th

century canon “Sumer is

icumen in” - a document of

native polyphony, with its

fondness for minor thirds

and sixths, the existence of

organs with over 400 pipes

as early as the 10th

century, the “Golden Age of

Music” at the time of

Shakespeare and, last but

not least, the present

renewed impetus through

composers like Vaughan

Williams, Tippet and Britten

are proof that the British

have good reason to consider

themselves a nation creative

in music, whose leading

representatives have

extended their artistic

influence to the Continent

as well.

It was during the reigns of

Elizabeth I (1558-1603) and

James I (1603-1625) that

musical activity reached a

peak. With the arrival on

the scene of the Italian

madrigal English composers

made up hundreds of

delightful choral songs to

the musical recipes of Luca

Marenzio and Giovanni

Gastoldi. Although written

in imitation of the Italian

form, in their melodic line,

their essence, their

interpretation of the words

and their popular vein these

songs always retained their

English character. This was

the heyday of keyboard

music, whose varied art

forms are contained in the

“Fitzwilliam Virginal Book”,

dance forms flourished, as

did the solo lute song,

which, under Dowland,

reached a perfection which

has remained unsurpassed.

The most outstanding

characteristic of this

classic epoch, however, was

the cultivation of chamber

music, which outstripped all

other instrumental and vocal

forms and only towards the

end of the 17th century

yielded ground to the more

expansive orchestral style

of France’s Lully. Known as

“consort music” this purely

instrumental ensemble music

has retained its vitality

right up to the present day.

Two to six performers

usually participated in such

communal music-making, which

was generally restricted to

a private circle without an

audience. It was considered

the done thing (and numerous

members of the nobility and

high-ranking citizens were

known to be competent

musicians) to play as many

instruments as possible. A

particularly revealing

description of the English

consort was given by the

German composer and theorist

Michael Praetorius: “A

consort is when several

persons with all kinds of

instruments such as

clavicymbal or large spinet,

large lyre, double harp,

lute, theorbo, bandora,

zither, viola da gamba, a

small descant viol, a flute

or recorder sometimes even a

quiet trombone or rackett,

in an ensemble and company,

made music in accord, quite

gently, soft and sweetly,

and in graceful symphony

play together with each

other.”

This “playing together with

each other” is to be taken

literally. The works

presented here require a

carefully balanced

combination of sound from

the chosen instruments -

unlike the mere grouping of

a number of different

instruments of earlier

times. It is just these

early steps in true

instrumentation that give

the music its peculiar

charm: viols, recorders and

lutes sound most convincing

when played in a restrained,

quiet and objective manner.

Its fine, delicate lines, in

which the upper melody part

does not yet bear the main

weight of the emotional

content, are brought out

best through a reserved,

tempered mode of playing -

subjective emotionalism in

the performer would simply

mean a grotesque caricature

and hysterical perversion of

the original.

Uwe

Kraemer

|

|

|

|