|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9546-A - (p) 1969

|

|

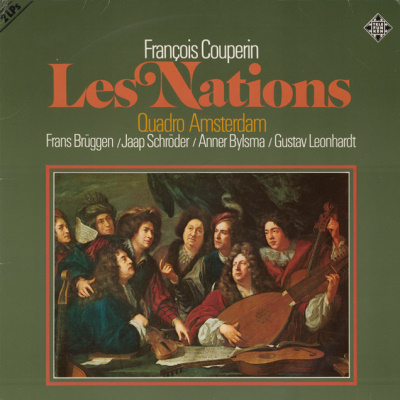

| 2 LPs -

6.48009 DX (TK 11550/1-2) - (p) 1969 |

|

| 2 CD -

4509-93689-2 - (c) 1994 |

|

LES NATIONS

(1726)

Sonates et Suites de Symphonies en

Trio. En quatre Livres séparés pour la

commodité des Académies de Musique et

des Concerts particuliers. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| François COUPERIN (1668-1733) |

Seconde

ordre: L'Espagnole [La Visionnaire] |

|

29' 51" |

A |

|

-

(Ouverture): Gravement et mesuré ·

Vivement · Air · Légèrement · Gayement ·

Air tendre · Vivement et marqué

|

7' 22" |

|

|

|

- Allemande

|

3' 18" |

|

|

|

-

Courante

|

1' 52" |

|

|

|

-

Seconde Courante

|

2' 11" |

|

|

|

-

Sarabande |

1' 47" |

|

|

|

-

Gigue Lourée

|

2' 57" |

|

|

|

-

Gavotte

|

1' 08" |

|

|

|

-

Rondeau

|

3' 00" |

|

|

|

-

Bourrée |

0' 59" |

|

|

|

-

Double de la Bourrée précédente

|

0' 56" |

|

|

|

-

Passacaille |

5' 07" |

|

|

|

Quatrième

ordre: La Piemontoise [L'Astrée]

|

|

21' 20" |

B |

|

-

(Ouverture): Gravement · Vivement ·

Gravement · Vivement et marqué · Air ·

Second Air · Gravement et marqué ·

Légèrement |

8' 07" |

|

|

|

-

Allemande |

2' 57" |

|

|

|

-

Courante |

1' 50" |

|

|

|

-

Seconde Courante

|

2' 26" |

|

|

|

-

Sarabande |

1' 58" |

|

|

|

-

Rondeau |

2' 10" |

|

|

|

-

Gigue |

2' 28" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

QUADRO AMSTERDAM

- Frans

Brüggen, Flute

- Jaap Schröder, Violin

- Anner

Bylsma, Violoncello

- Gustav Leonhardt, harpsichord

with:

Marie

Leonhardt, Violin

Frans Vester, Flute

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bennebroek (Holland)

- Novembre 1968

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9546-A | 1 LP -

durata 51' 21" | (p) 1969 | ANA

Telefunken |

6.48009 DX | 2 LPs - durata 54'

00" - 51' 21" | (p) 1969 | ANA |

Riedizione (Ordres I-II-III-IV)

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 6019 | 4509-93689-2 | 2 CDs -

durata 53' 06" - 51' 41" | (c)

1994 | ADD | (Produzioni

I-II-III-IV) |

|

|

Cover

|

|

Meeting of musicians

and singers. Painting by François

Puget (1640-1707).

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

When François

Couperin published his

collection of suites

“Les Nations” in 1726,

the four suites it contained

had already been

circulating in

manuscript for more

than thirty

years - except for

“L’Impériale”

(SAWT 9476-A),

which was not

composed until ca.

1725. In

his preface

the composer

describes how,

at the age of

twenty-four, he

had introduced

his trio sonatas

under a

pseudonym:

“It has

already been

several years

since some of

these trios were

composed. Several

of those

manuscripts have

circulated,

which I distrust

because of

the negligence of

copyists. From time

to time I

have added

to their

number, and I

believe that the

lovers of truth

will be

pleased with

them. The

first sonata

in this

collection was

also the

first that I

composed and

the first

that was

composed in

France. The

story of it is

curious in itself.

“Charmed by

those [sonatas]

of Signor

Corelli, whose

works I shall

love as long

as I live,

much as [I

shall love] the

French works of

Monsieur de

Lully, I attempted

to compose

one, which I

[then] had

performed in

the concert-hall

where I had

heard those of

Corelli. Knowing

the greediness

of the French

for foreign

novelties above

all else,

and lacking

confidence in

myself, I did

me a very

neat service by

means of a

convenient

little ruse. I

pretended that

a kinsman

of mine - in the

service of the

King of

Sardinia, to

be exact - had

sent me a

sonata by a

recent Italian

composer. I

rearranged the

letters of my

name so that it

became an

Italian name, which I

used instead.

The sonata

was devoured

eagerly and I

felt vindicated by

it. Meanwhile,

that [success]

gave me

[further]

courage. I wrote

others; and my

Italianized name

brought much

applause to

me, under

the disguise.

Fortunately, my

sonatas won

enough favour

that the

deception did

not embarrass me

at all. I

have compared

these sonatas

with those

that I wrote since,

and have neither

changed nor

added much

of importance. I

have only

added some big

suites of

pieces to

which the

sonatas serve

merely as

preludes or

kinds of

introductions.”

In this

manner,

Couperin, whom

the contemporary

writer on

music Le Cerf de la

Viéville (1647-1707)

reproached as a

“serviteur

passioné

d’Italie” in

this connection,

had combined

the sonata da

chiesa (the

Italian

contribution to

the suite form

of the

seventeenth

century) with

old dance

forms and

the contemporary

fashionable French

dances. This

new kind

of “réunion

des deux gouts”

immediately

became the

subject of

lively

discussion in

France, and

eventually the

predominant mode of

writing.

Couperin had

succeeded in

combining the

foreign and the

native, the

styles of Italy

(the sonata in

the form of

the sonata da

chiesa) and of

France (the

suite) so

homogeneously

that something

new had

been created

which could

never again be

separated.

All four

sonatas of

“Les Nations”

are written

for two “dessus”

(melodic

instruments not

further specified), a “basse

d’archet” (bowed bass =

viola da gamba) and

a keyboard

instrument

supporting the

bass, though not

always doubling

it as a basso

continuo. (Marin

Mersenne [1588-1648],

still the

leading French

musical theoretician in

Couperin’s time,

understood by “dessus”

only the

uppermost part

in five-part

string writing.)

Performance on

other

intruments, such

as two

keyboard

instruments

only, was

left expressly

to the

discretion of

the performer by

Couperin in

1725 (in the

“Apothéose de

Lulli”). In our

recording the

two treble parts

are played on

the flute

and the violin,

either two

of the same

instrument being

used or

one of

each. The

unusually rich

ornamentation

will be

the first thing

to strike

the attentive

listener,

Couperin has

given exact

instructions for

the execution of

these ornaments in

his “L’art de toucher

le clavecin”. J. S.

Bach also made

use of these

instructions

when he

provided the

“Klavierbüchlein für

Friedemann Bach”

with a table of

ornaments after

Couperin’s model.

The names

of the

four trio

sonatas must

not be

taken too

seriously, let

alone as

programmes; they

are more of

a label

than an

attempt at

description.

This already

becomes evident

from the fact

that the

two trio

sonatas in this

recording, “L’Espagnole” and

“La Piemontoise”, are

called “La

Visionnaire” and

“L’Astrée” in their

original form of

around 1692.

Both begin

with an

Italian “Sonade”

in a

predominantly

contrapuntal

style of

writing after

the manner

of Corelli, with

a double or

triple

slow-quick

sequence of

movements

generally

leading into

one another

without a

break. This

is followed by

the French suite

with a

loose sequence

of dance

movements. It

is here

that Couperin

shows his

greatest

artistic maturity,

particularly in

the Allemandes

and Courantes,

with their

Italianate

melodiousness of

the upper

part and

harmonious

fullness of

tone in

the lower

parts while

still preserving

the French form.

In

“L’Espagnole”,

the suite

following the

“Sonade” is

concluded by a

big fugal

Passacaille,

while “La

Piemontoise”

ends with two

movements

roughly equal

in weight:

a light-footed

Rondeau and

a melancholy,

dance-like Gigue

in which the

minor key

of the

sonata’s opening

returns. But

this minor

character is

not a key

as used

later on

in the classical

period; it

rather

fluctuates

iridescently

between major

and minor

sevenths, sixths

and thirds. François

Couperin’s music

displays the

harmonic style

characteristic

of France’s

early and

high baroque

style, which

still represents

a transition

from the old

modal tonality

to the

classical,

clearly defined

major-minor key

relationship.

Unlike his

contemporaries, he

indeed stands

on the

threshold of the

rococo, yet does

not actually

provide a

link between

the baroque,

the rococo

and the classical.

Just as

Johann Sebastian

Bach appears

as the

keystone in

the vaulting of

the German

baroque in

music, so Couperin

unites in

himself the

baroque traditions of

French music,

and has no

reason to

shun comparison

with the great

German master.

Klaus

L. Neumann

|

|

|

|