|

|

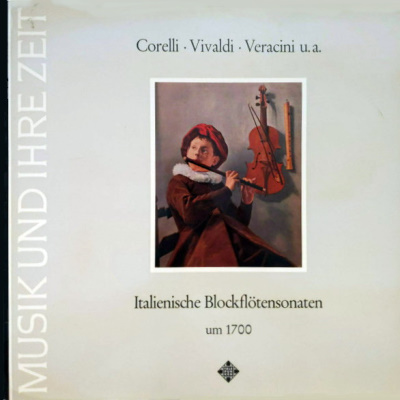

1 LP -

SAWT 9518-A - (p) 1968

|

|

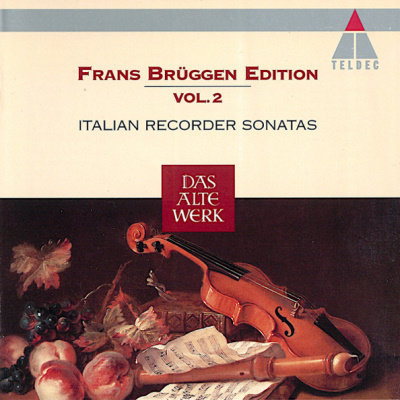

| 1 CD -

4509-93669-2 - (c) 1995 |

|

| ITALIENISCHE

BLOCKFLÖTENSONATEN UM 1700 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arcangelo CORELLI

(1653-1713) |

Variationen

über "La Follia" für Blockflöte in f'

und Bc., Op. 5, Nr. 12 |

|

10' 00" |

A1 |

|

-

(Adagio · Allegro · Adagio · Vivace ·

Allegro · Andante · Allegro · Adagio ·

Allegro) |

|

|

|

| Francesco BARSANTI (geb. um 1690) |

Sonate

C-dur für Blockflöte in f' und Bc.

|

|

7' 30" |

A2

|

|

aus

"Sonatas or Solos for a Flute with a

Thorough Bass for the Harpsichord or

Bass Violin compos'd by Francesco

Barsanti" |

|

|

|

|

-

(Adagio · Allegro · Largo · Presto) |

|

|

|

| Francesco Maria

VERACINI (1690-1768) |

Sonate G-dur für Blockflöte in

f' und Bc.

|

|

8' 45" |

B1 |

|

Sonata

seconda aus "Sonate / a Violino, o

Flauto solo e Basso / dedicate /

All'Altezza Reale / Del Serenissimo

Principe Elettorale / di Sassonia / da

Francesco Maria Veracini / Fiorentino /

Venezia, 26 Luglio 1716 |

|

|

|

|

-

(Largo · Allegro · Largo · Allegro) |

|

|

|

| Diogenio BIGAGLIA (unbekannt - um 1700)

|

Sonate

a-moll für Blockflöte in b' und Bc.

- Sonata a Fluta di quatre e Basso

|

|

7' 06" |

B2 |

|

-

(Adagio · Allegro · Tempo di Minuetto ·

Allegro) |

|

|

|

| Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) |

Sonate

g-moll für Blockflöte in f' und Bc.,

Op. 13, Nr. 6 |

|

7' 45" |

B3 |

|

aus

"Il Pastor Fido" / "Sonates / pour / La

Musette, Viele, Flûte, Hautbois, Violon

/ Avec la Basse Continue / del Sig' /

Antonio Vivaldi / opera XIII / ...Paris

/ Chez M Boivin M.de, rue St. Honoré à

la règle d'or / Avec Privilège du Roy,

Paris le 17 avril 1737 |

|

|

|

|

-

(Vivace · Alla breve · Largo · Allegro ma

non presto) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frans

BRÜGGEN, Blockflöten:

- Descant recorder in b flat ("fourth

flute" by P. I. Bressan, London, beginning

of 18th century, from the provate

collection of Edgar Hunt, Chesham Bois,

England

- Treble recorder in f, copy by Martin

Skowroneck, Bremen 1966, after the Treble

recorder by P. I. Bressan

Anner BYLSMA, Violoncello

(Giovanni Battista (II) Guadagnini, 1749)

Gustav LEONHARDT, Cembalo (after

J. D. Dulcken, Antwerp 1745, by Martin

Skowroneck, Bremen 1963)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bennebroek (Holland)

- Febbraio 1967

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9518-A | 1 LP -

durata 41' 06" | (p) 1968 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics

"Frans Brüggen Edition" Vol. 2 |

LC 6019 | 4509-93669-2 | 1 CD -

durata 72' 43" | (c) 1995

| ADD

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

Judith Leyster:

"Flötenspieler". Nationalmuseum

Stockholm.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Corelli’s

variations on La Folia, from

the beginning of the 18th

century the composer’s most

famous work, were originally

written for violin and

figured bass and constitute,

in this version, the last of

the twelve “Sonate a violino

e violone o cimbalo”, which

first appeared in Rome with

the superscription of 1st

January 1700, and by 1720

saw no fewer than twenty

reprintings, above all in

Amsterdam and London. The

present version for recorder

(in which the only

simplifications are of

technical peculiarities like

the chords or

double-stopping of the

violin version) had already

been published in 1702 by

Walsh in London. The

imaginative title “La Folia”

(Walsh wrote “La Follia”)

denotes nothing more than

that the work is constructed

on the bass pattern known as

a ‘folia’, which first

emerged in Spanish and

Italian music of the early

16th century as a bass (i.

e. as a harmonic framework)

for vocal and instrumental

movements, and thence,

partly also combined with a

more or less fixed or varied

upper melodic Part, set out

on its victorious path

through Europe. In the

instrumental music of

Corelli’s time, particularly

in the sets of variations,

this pattern attained its

richest flowering - not only

Corelli himself, but also

Pasquini, d’Anglebert,

Cabanilles, Marais and

Alessandro Scarlatti wrote

sets of variations on La

Folia, in so doing giving

free rein to their

imagination, particularly

from the point of view of

technique.

Corelli’s “sonata” is

planned as a sequence of ‘a

theme and 21 variations. The

theme preserves, along with

the traditional 3/4 measure,

the traditional descant

melody and its sarabande

character; thereafter

movement and melodic

figuration are increased

from variation to variation,

and rhythm, tempo and

compositional technique

constantly changed, while

the harmonic movement and

its symmetric organisation

(4+4, 4+4 bars, both halves

repeated) remain firmly

fixed. The frequent

recurrence of long phrases

building up from grave

crotchet movement in

sarabande rhythm to

virtuosic semiquaver

figurations in the separate

movements gives the work its

inner coherence and its

accompanying dynamics; the

abundance of ingenious

melodic and constructional

ideas and the extraordinary

technical demands lend it

that range of colour and

that air of fantasy which

already fascinated its

contemporaries and made the

work so uniquely famous.

An entirely different

picture is offered in

Barsanti’s flute sonata,

which comes from “Sonatas or

Solos for a Flute with a

Thorough Bass”, first

published in 1724. Barsanti

belongs to that large number

of Italian instrumental

composers who, in view of

the dearth of purely

instrumental music at home,

sought their fortune abroad.

Born about 1690 in Lucca, he

went with Geminiani to

England, where he worked

partly in London, partly in

Scotland, until he died,

half forgotten, in London at

some unknown point of time

between 1750 and 1776. His

attractive and technically

highly demanding sonata

reveals him as a

considerable flautist and as

a composer who (as in his

concerti grossi) stands very

close to Geminiani, his

companion in travel and

fortune. The introductory

Adagio transforms the

pathetic-expressive style of

the Italian high-baroque

into a sensitive, elegant

figuration rich in sighs,

delicate melodic suspensions

and chromaticisms. The first

Allegro, with its energetic,

characteristic principal

subject, suggests a concerto

movement by Vivaldi; it is

followed by a considerable A

minor Largo, which with its

wide-ranging melody and bass

lines and its mixture of

pathos and tender rapture

particularly and strikingly

recalls Geminiani. The last

movement begins as a typical

dance-like 3/8 finale but

strikes a more serious note

in its broad melodic arches

and colourful harmony. The

sonata by Veracini comes

from an early work by the

composer, the “Sonate a

Violino, o Flaute solo, e

Basso”, which the young

virtuoso, already famous,

presented in 1716 in Venice

to Prince Friedrich August

of Saxony on his Italian

journey. Veracini’s strongly

individual style is already

plainly shown here: above

all the mixture of baroque

and pre-classical elements

is outstanding and

attractive. The introductory

12/8 Largo is a still

entirely baroque Siciliano,

which affirms the

traditional pastoral nature

of this type of movement

with little echoes and a

sentimentally sweet,

uninterruptedly emphatic

flowing cantilena. The

following Allegro, in

contrast, is already almost

an early classical movement

of the divertimento type -

an artless but always

charming and tasteful

succession of precise,

melodically pregnant motifs

in regular four-bar groups.

The E minor Largo begins

with a pathetic, broad

baroque melody but soon

changes to a succession of

almost “galant” small motifs

with the typical dotted

rhythm and the “speaking”

melodic flourishes of the

new era. The finale is an

entirely “modern” 3/8 final

dance, formally a fully

developed sonata movement

with new ideas in the middle

section: a most gay, witty

and virtuoso piece of

considerable proportions.

The sonata of the Venetian

Dominican friar Bigaglia, of

whose life we know almost

nothing, is one of the very

few surviving works for

fourth flute - apart from

two suites by Dieupart the

only one known up till now.

The manuscript reveals a

charming, if not exactly a

profound, talent between

Vivaldi and Galuppi; the

form and construction of the

sonata indicate a truly

“progressive” spirit which,

with a pleasure in

experimentation, took up and

worked on what was musically

in the air of Venice. Thus

the traditional form of the

sonata da chiesa is

completely abandoned, and

elements of the suite and

the concerto intervene. The

first movement is an Adagio,

more graceful than serious,

cantabile and with

typically “modern” dotted

rhythms over a very simple

bass; the ensuing Allegro,

straightforwardly song-like

in its phrasing, approaches

sonata form and is

characterised by an

animated, simple dance

melody. The Tempo di

Minuetto is already a quite

“galant” Italian minuet,

almost foreshadowing

Sammartini, with harmonic

twists of charmingly naive

coloration in the middle

section. The finale is

presented asa brisk concerto

movement, whose pregnant and

animated principal subject

could have been picked up

from Vivaldi.

Perhaps the most noteworthy

work on our record is the

sonata from Vivaldi’s Op. 13

“II Pastor fido, Sonates

pour la Musette, Viele,

Flûte, Hautbois, Violon avec

la Basse Continue”. The

publication appeared

conspicuously late, in 1737

in Paris; on the other hand

the genrelike character of

the sonatas and the equally

genre-like

ornamentation in the

instrumentation more

probably indicate an early

period of origin - if, that

is, the ornaments,

appropriate to the bagpipe

and hurdy-gurdy, are not an

invention of the publisher,

in whose French milieu

they are essentially more

fitting than in Vivaldi’s

own Venetian surroundings.

The G minor sonata is the

most “serious” of the six

works, and that which bears

the least pastoral

character: in form it

differs from the traditional

sonata da chiesa only in

that there is at the

beginning a dance-like 3/8

Vivace, a short movement

quickly flashing by, which

in the middle section plays

very wittily with irregular

phrase construction. This is

followed by a lively “fugue”

for two voices with an

obbligato counterpoint. The

third movement, a charming

9/8 Siciliano, is the first

to affirm the pastoral

sphere suggested by the

title of the publication.

The finale is a spirited

concerto movement on one of

those energy-laden,

pathetic-gesture minor

themes which make Vivaldi’s

style so unmistakable - and

which had already

established his fame among

his contemporaries.

Ludwig

Finscher

The

recorder and recorder

music in the early 18 th

century

The period to which the

present recording is

dedicated marks the final

flowering of recorder

playing and recorder music

in baroque Europe. While in

Italy at the end of the 17th

century the century-old

tradition of the instrument

was already beginning to

fade, supplanted above all

by the violin as the new

expressive solo instrument

par excellence, the “flauto

dolce” experienced a last

flowering in Germany, France

and England - particularly

in England, where

middle-class domestic music

had already so favoured the

instrument throughout the

17th century that on the

Continent it could be called

simply “flûte d’Angleterre”.

The pre-requisites for the

new blossoming of recorder

music were created in the

second half of the 17th

century by the adaptation of

the instrument, rich in

tradition, to the new tonal

ideal of the high and late

Baroque, the transformation

of its “quiet, delightful

harmony” (Michael

Praetorius) into a stronger,

brighter and sharper sound,

which could assert itself in

the multi-coloured orchestra

of about 1700 and at the

same time was suitable to

the technical demands of the

increasingly virtuosic

chamber music. This

metamorphosis of the

instrument seems to have

emanated shortly after 1650

from France, where by means

of technical alterations the

compass was extended to more

than two octaves, the tone

was made fuller and more

penetrating but at the same

time clearer and “sweeter”,

so that the designation

“flauto dolce” was now fully

justified. The new type of

flute spread with manifest

speed towards England and

Germany in particular. At

the same time the recorder

“family”, which had

satisfied the tonal ideal of

the Renaissance and early

Baroque, was gradually

reduced to the diskant

and alt recorders,

of which the diskant

(whose compass was f to g’”)

was by far the more

prevalent - the same

instrument which best

maintained the function of

carrying the upper part in

the baroque orchestra and

which in chamber music for

solo instruments was most

versatile in use and most

easily called upon for

alternative casting, as the

numerous headings for

“flauto o violino” etc.

indicate.

The instruments in our

recordings were constructed

after two models of

exceptional quality,

instruments of the London

flute-maker P. I. Bressan at

the beginning of the 18th

century. Both are of

boxwood. Bressan’s F

recorder (in pitch about 3/4

tone below today’s concert

pitch) is decorated in

ivory, and its tone is

unusually full and strong.

The “fourth flute” (“flûte

de quatre”), a rare but

attractive variety of late

recorder development, is

built, as its name suggests,

a fourth higher, i.e. in b

flat. Its tone is unusually

“round” and powerful. Both

instruments clearly show

that decisive characteristic

of late Baroque

flute-making, which with

mechanised mass manufacture

is inevitably lost - the

individuality of tone, the

pronounced “character” of

every single instrument

built slowly and lovingly by

hand.

Although the recorder as an

orchestral and chamber music

instrument at the start of

the 18th century - above all

in France - found a

dangerous and eventually

victorious rival in the

technically ever-improving

transverse flute, which was

forging ahead, at all events

the chamber-music flute

literature of the first half

of the 18th century is

certainly to be understood

primarily as recorder

literature - which did not,

according to the principle

of freedom of instrumental

interchange, prevent

recorder and transverse

flute, violin and oboe being

used instead of one another.

While the Italian flute

literature of the time is

not very rich and largely

concentrates on alternative

versions (“flauto o

violino”), in Germany and

France it attained a richer

repertoire - the works of

Telemann, Dieupart and

Jean-Baptiste Loeillet are

especially outstanding here

(cf. also Das alte Werk,

SAWT 9482-A: Recorder music

circa 1700 on original

instruments). The centre of

recorder playing and

recorder composition in

chamber music seems to have

been London - not for

nothing were most of the

flute tutors, and most of

the flute works of Italian

composers also, brought out

here, but also those

numerous (musically mostly

primitive) arrangements of

popular songs, opera arias

and abridgements of whole

operas for recorder, which

are an infallible indication

of an instrument’s culture,

branching out in all strata

of amateur music-making. Of

the works in our recording

two - the Corelli and

Barsanti - appeared in

London, a third - the

Bigaglia - in Amsterdam,

whose music publishing world

had close ties with that of

the English metropolis.

Ludwig

Finscher

(translated

by Lionel Salter)

|

|

|

|