|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9496-A - (p) 1967

|

|

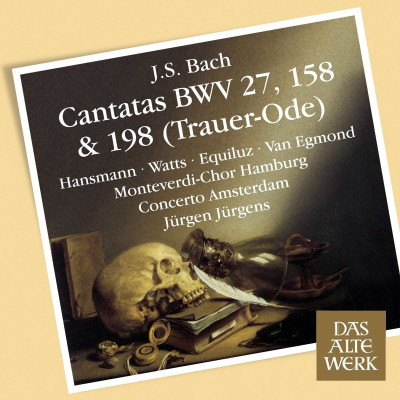

| 1 CD -

2564-64673-2 - (c) 2013 |

|

KANTATE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Kantate

"Laß Fürstin, laß noch einen Strahl",

BWV 198 - Leipzig 17. Oktober 1727 |

|

35' 19" |

|

|

Trauer-Ode

auf das Ableben der Gemahlin Augusts des

starken - Christiane Eberhardine, Königin

vol Polen und Kurfürstin von Sachsen

für Sopran, Alt, Tenor, Baß, Chor, 2

Traversflöten, 2 Oboen d'amore, 2

Lauten, Violinen I und II, Bratschen, 2

Violen da gamba, Continuo (Vcl.,

Violone, Cembalo e Organo) |

|

|

|

|

Erster Teil

|

|

23' 30"

|

|

|

- Coro: "Laß, Fürstin, laß noch

einen Strahl"

|

6' 11" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Dein Sachsen, dein

bestürztes Meißen" |

1' 15" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Verstummt, ihr holden

saiten"

|

4' 04" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Recitativo (Alt): "Der Glocken bebendes

Getön" |

0' 47" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Aria (Alt): "Wie starb die Heldin so

vergnügt" |

7' 46" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Recitativo (Tenor): "Ihr Leben ließ die

Kunst zu Sterben"

|

1' 11" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Coro: "An dir, du Vorbild großer Frauen"

|

2' 16" |

|

B2 |

|

Zweiter Teil

|

|

11' 49" |

|

|

-

Aria (Tenor): "Der Ewigkeit saphirnes

Haus"

|

4' 06" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Recitativo (Baß): "Was Wunder ist's? Du

bist er wert" - Arioso: "So weit der volle

Weichselstrand" |

2' 32" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Coro: "Doch, Königin! du stirbest nicht" |

5' 11" |

|

B5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Rohtraud

Hansmann, Sopran

Helen

Watts,

Alt

Kurt

Equiliz, Tenor

Max

van Egmond, Baß

|

MONTEVERDI-CHOR HAMBURG

CONCERTO AMSTERDAM | Jaap

Schröder, Konzertmeister

Frans Vester, Joost Tromp, Querflöte

Lilian Lagaay, Ad Mater,

Oboe d'amore

Eugen M. Dombois, Gusta

Goldschmidt, Laute

Veronika Hampe, Wielan

Kuijken, Gambe

Gustav Leonhardt, Orgel und

Cembalo

Jürgen JÜRGENS, Gesamtleitung

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hervormde Kerk,

Bennebroek (Holland) - 9/13 Giugno

1966

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9496-A | 1 LP -

durata 35' 19" | (p) 1967 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics

"Das Alte Werk | LC 04281 |

2564-64763-2 | 1 CD - durata 66'

44" | (c) 2013 | ADD

|

|

|

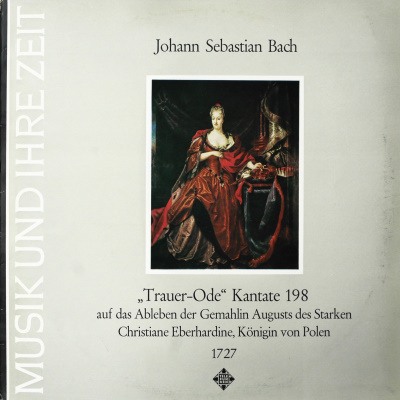

Cover

|

|

Princess Eberhardine,

Wife of Augustus I, unknown master

of the 18th century.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

In spite of

the widespread interest in

and knowledge of Bach’s work

nowadays, the “Funeral Ode”

still remains one of the

least known works of this

former Cantor of St. Thomas’

Leipzig. This is

understandable if one

considers the text on its

own - written for a

particular occasion in a

particular age - but not

understandable when one

appreciates what Bach did

with the text.

The work was probably

written in Leipzig in the

short time of two weeks in

October 1727 and was

completed on the 15th of

that month. A month earlier

on the 5th of September 1727

the Electress of Saxony and

Queen of Poland, Christiane

Eberhardine, had died.

Unlike her husband,

Frederick Augustus II, she

had remained a Protestant,

and after his conversion in

1697 withdrew to her Palace

at Pretzsch, near

Wittenberg. As a defender of

her faith she enjoyed the

highest esteem and love in

predominantly Protestant

Saxony and especially in

Leipzig. It was only natural

then that Leipzig should be

the scene of a great

Memorial Service. A student

of noble descent, Carl von

Kirchbach, took the

initiative and extracted

from the Elector the

permission to hold a

University service at which

he intended to make the

funeral oration. Funeral

music was a requisite part

of such a ceremony.

Kirchbach asked no lesser

persons than Gottsched to

write the text and the

Cantor of St. Thomas’ to

compose the music. In making

this request to Bach he

passed over the University

Cantor, Johann Gottlieb

Görner, the person actually

responsible for academical

ceremonies. The latter

promptly tried to get hold

of the commission himself or

at least. to be responsible

for the performance,

however, without success. On

the 17th of October the

bells of all the city

churches tolled as the

procession made its way to

the University Church where

the Memorial Service took

place with great pomp and

ceremony. Bach conducted the

performance of his work from

the harpsichord.

The cantata in the broadest

sense of the word - whether

as the church cantata or the

patrician, academic or

courtly work of musical

homage and festivity -

accompanied the Arnstadt and

Mühlhausen organist, the

Weimar chamber musician and

court organist, the Köthen

conductor and finally the

Leipzig cantor of St.

Thomas’-Bach-all through his

creative life, although with

fluctuating intensity, with

interruptions and

vacillations that still are

problems to musicological

research down to this very

day. The earliest preserved

cantata (“Denn du wirst

meine Seele nicht in der

Hölle lassen”) probably

dates, if it really is by

Bach, from the Arnstadt

period (1704) and is still

completely under the spell

of North and Central German

traditions. In the works of

his Mühlhausen years

(1707-08) - psalm cantatas,

festive music for the

changing of the council and

a funeral work (the “Actus

tragicus”) - we sense for

the first time something of

what raises Bach as a

cantata composer so much

higher than all his

contemporaries: the ability

to analyse even the most

feeble text with regard to

its form and content, to

grasp its theological

significance and to

interpret it out of its very

spiritual centre in musical

“speech” that is infinitely

subtle and infinitely

powerful in effect. In

Weimar (1708-17) new duties

pushed the cantata right

into the background to begin

with. It was not until the

Duke commissioned him to

write “new pieces monthly”

for the court services that

Bach once more turiied to

the cantata during the years

1714-16, on texts written by

Erdmann Neumeister and

Salomo Franck. Barely thirty

cantatas can be ascribed to

these two years with a

reasonable degree of

certainty. It is most

remarkable that, on the

other hand, no courtly

funeral music has been

preserved from the entire

Weimar period, although

there must have been a

considerable demand for such

works. It is conceivable

that many a lost work,

supplied with a new text by

Bach himself, lives on among

the Weimar church cantatas.

In the years Bach spent at

Köthen (1717-23), on the

other hand, it is the

composition of works for

courtly occasions of homage

and festivity that come to

the fore, entirely in

keeping with Bach’s duties

as Court Conductor. It is

only during the last few

months he spent at Köthen

that we find him composing a

series of church cantatas

once again, and these were

already intended for

Leipzig. It was in Leipzig

that the mojority of the

great church cantatas came

into being, all of them -

according to the most recent

research - during his first

few years of office at

Leipzig and comprising

between three and a maximum

of five complete series for

all the Sundays and feast

days of the ecclesiastical

year. But just as suddenly

as it began, this amazing

creative flow, in which this

magnificent series of

cantatas arose, appears to

have ended again. It is

possible that Bach’s regular

composition of cantatas

stopped as early as 1726;

from 1729 at the latest it

is evident that other tasks

largely absorbed his

creative energy,

particularly the direction

of the students’ Collegium

Musicum with its perpetual

demand for fashionable

instrumental music. More

than 50 cantatas for courtly

and civic occasions have

indeed been recorded from

later years, but considered

over a period of 24 years

and compared with the

productivity of his first

years in Leipzig they do not

amount to very much. We are

left with the picture of an

enigmatic silence in a

sphere which has ever

counted as the central

category in Bach’s creative

output.

But we only need cast a

superficial glance at the

more than 200 of the

master’s cantatas that have

come down to us in order to

see that this conception of

their position in Bach’s

total output is fully

justified. Bach has

investigated their texts

with regard to both their

meaning and their wording

with incomparable

penetration, piercing

intellect and unshakeable

faith, whether they are

passages from the Bible,

hymns, sacred poems by his

contemporaries or sacredly

trimmed poetry for courtly

occasions. He has

transformed and interpreted

these texts through his

music with incomparable

powers of invention and

formation, he has revealed

their essence and, at the

same time, translated the

imagery and emotional

content of each to their

ideas into musical images

and emotions. The perfect

blending of word and note,

the combination of idea

synthesis and depiction of

each detail of the text, the

joint effect of the baroque

magnificence of the musical

forms and the highly

differentiated attention to

detail, the skillful balance

between contrapunctal,

melodic and harmonic means

in the service of the word

and, not least, the

inexhaustible fertility and

greatness of a musical

imagination that is able to

create from the most feeble

‘occasional’ text a world of

musical characters - all

this is what raises the

cantata composer Bach so

much higher than his own and

every other age and their

historically determined

character, and imparts a

lasting quality of his

works. It is not their texts

alone and not their music

alone that makes them

immortal - it is the

combination of word and note

into a higher unit, into a

new significance that first

imparts to them the power of

survival and makes them what

they are above all else:

perfect works of art.

|

|

|

|