|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9513-B - (p) 1966

|

|

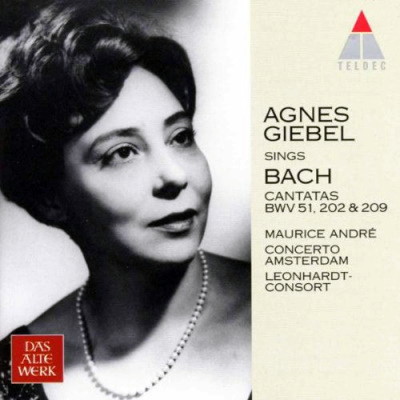

| 1 CD -

3984-21711-2 - (c) 1998 |

|

SOLO-KANTATEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Kantate

"Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen", BWV

51 - Kantate am fünfzehnten Sonntag nach

Trinitatis und für allezeit |

|

18' 00" |

|

|

für

Solo-Sopran; Troba (Trompete); Violine

I, II; Viola und Continuo |

|

|

|

|

- Aria (Sopran): "Jauchzet Gott in

allen Landen!"

|

5' 00" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Wir beten zu dem

Tempel an"

|

2' 15" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Höchster, mache deine

Güte"

|

4' 15" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Choral: "Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren" |

4' 15" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Alleluja!" |

2' 15" |

|

A5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kantate

"Weichet nur, betrübte Schatten"

(Hochzeitskantate), BWV 202

|

|

20' 32" |

|

|

für

Solo-Sopran; Oboe; Violinen I, II; Viola

und Continuo |

|

|

|

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Weichet nur, betrübte

Schatten"

|

6' 20" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Die Welt wird wieder

neu" |

0' 30" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Phoebus eilt mit schnellen

Pferden" |

3' 25" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Drum sucht Amor sein

Vergnügen" |

0' 37" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Wenn die Frühlingslüfte

streichen" |

2' 30" |

|

B5 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Und diesis ist das

Glücke" |

0' 45" |

|

B6 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Sich üben im Lieben" |

4' 20" |

|

B7 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "So sei das Band der

keurschen Liebe" |

0' 25" |

|

B8 |

|

-

Gavotte (Sopran): "Sehet in Zufriedenheit" |

1' 40" |

|

B9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Agnes Giebel, Sopran

Maurice

André,

Trompete (BWV 51)

Ad Mater, Oboe

(BWV 202)

Jaap Schröder, Violine

Jacques Holtman, Violine (BWV

51)

Anner Bylsma, Violoncello

Gustav Leonhardt, Orgel

[Positiv] (BWV 51) und Cembalo (BWV

202)

CONCERTO AMSTERDAM

Jaap SCHRÖDER, Konzertmeister

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bennebroek (Holland)

- Gennaio 1966

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9513-B | 1 LP -

durata 38' 32" | (p) 1966 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 6019 | 3984-21711-2 | 1 CD -

durata 68' 48" | (c) 1998 | ADD

|

|

|

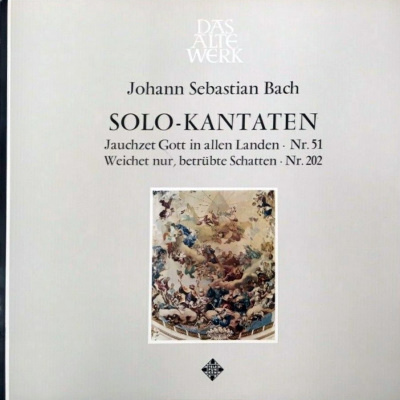

Cover

|

|

"Die Anbetung der

heiligen Dreifaltigkeit".

Deckengemälde in der Klosterkirche

Veresheim von Martin Knoller.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The cantata in

the broadest sense of the

word - whether as the church

cantata or the patrician,

academic or courtly work of

musical homage and festivity

- accompanied the Arnstadt

and Mühlhausen organist, the

Weimar chamber musician and

court organist, the Köthen

conductor and finally the

Leipzig cantor of St.

Thomas’-Bach-all through his

creative life, although with

fluctuating intensity, with

interruptions and

vacillations that still are

problems to musicological

research down to this very

day. The earliest preserved

cantata (“Denn du wirst

meine Seele nicht in der

Hölle lassen”) probably

dates, if it really is by

Bach, from the Arnstadt

period (1704) and is still

completely under the spell

of North and Central German

traditions. In the works of

his Mühlhausen years

(1707-08) - psalm cantatas,

festive music for the

changing of the council and

a funeral work (the “Actus

tragicus”) - we sense for

the first time something of

what raises Bach as a

cantata composer so much

higher than all his

contemporaries: the ability

to analyse even the most

feeble text with regard to

its form and content, to

grasp its theological

significance and to

interpret it out of its very

spiritual centre in musical

“speech” that is infinitely

subtle and infinitely

powerful in effect. In

Weimar (1708-17) new duties

pushed the cantata right

into the background to begin

with. It was not until the

Duke commissioned him to

write “new pieces monthly”

for the court services that

Bach once more turned to the

cantata during the years

1714-16, on texts written by

Erdmann Neumeister and

Salomo Franck. Barely thirty

cantatas can be ascribed to

these two years with a

reasonable degree of

certainty. It is most

remarkable that, on the

other and no courtly funeral

music has been preserved

from the entire Weimar

period, although there must

have been a considerable

demand for such works. It is

conceivable that many a lost

work, supplied with a new

text by Bach himself, lives

on among the Weimar church

cantatas.

In the years Bach spent at

Köthen (1717-23), on the

other hand, it is the

composition of works for

courtly occasions of homage

and festivity that come to

the fore, entirely in

keeping with Bach’s duties

as Court Conductor. It is

only during the last few

months he spent at Köthen

that we find him composing a

series of church cantatas

once again, and these were

already intended for

Leipzig. It was in Leipzig

that the majority of the

great church cantatas came

into being, all of them -

according to the most recent

research - during his first

few years of office at

Leipzig and comprising

between three and a maximum

of five complete series for

all the Sundays and feast

days of the ecclesiastical

year. But just as suddenly

as it began, this amazing

creative flow, in which this

magnificent series of

cantatas arose, appears to

have ended again. It is

possible that Bach’s regular

composition of cantatas

stopped as early as 1726;

from 1729 at the latest it

is evident that other tasks

largely absorbed his

creative energy,

particularly the direction

of the students’ Collegium

Musicum with its perpetual

demand for fashionable

instrumental music. More

than 50 cantatas for courtly

and civic occasions have

indeed been recorded from

later years, but considered

over a period of 24 years

and compared with the

productivity of his first

years in Leipzig they do not

amount to very much. We are

left with the picture of an

enigmatic silence in a

sphere which has ever

counted as the central

category in Bach’s creative

output.

But we only need cast a

superficial glance at the

more than 200 of the

master’s cantatas that have

come down to us in order to

see that this conception of

their position in Bach’s

total output is fully

justified. Bach has

investigated their texts

with regard to both their

meaning and their wording

with incomparable

penetration, piercing

intellect and unshakeable

faith, whether they are

passages from the Bible,

hymns, sacred poems by his

contemporaries or sacredly

trimmed poetry for courtly

occasions. He has

transformed and interpreted

these texts through his

music with incomparable

powers of invention and

formation, he has revealed

their essence and, at the

same time, translated the

imagery and emotional

content of each of their

ideas into musical images

and emotions. The perfect

blending of word and note,

the combination of idea

synthesis and depiction of

each detail of the text, the

joint effect of the baroque

magnificence of the musical

forms and the highly

differentiated attention to

detail, the skillful balance

between contrapuntal,

melodic and harmonic means

in the service of the word

and, not least, the

inexhaustible fertility and

greatness of a musical

imagination that is able to

create from the most feeble

‘occasional’ text a world of

musical characters - all

this is what raises the

cantata composer Bach so

much higher than his own and

every other age and their

historically determined

character, and imparts a

lasting quality to his

works. It is not their texts

alone and not their music

alone that makes them

immortal - it is the

combination of word and note

into a higher unit, into a

new significance that first

imparts to them the power of

survival and makes them what

they are above all else:

perfect works of art.

····················

Among

the two hundred church

cantatas by Bach that have

been preserved, there is a

small group of works not

written for the normal large

“concerto” forces (soli,

chorus and orchestra), but

for a solo voice and a small

instrumental ensemble, often

enriched by a solo

instrument. These are the

alto cantatas “Geist und

Seele sind verwirret” (with

concertante organ),

“Widerstehe doch der Sünde”,

“Vergnügte Ruh, beliebte

Seelenlust” (with

concertante organ) and the

aria “Bekennen will ich

seinen Namen”, the soprano

cantatas “Jauchzet Gott”

(with concertante trumpet)

and “Mein Herze schwimmt in

Blut” (with concertante

oboe) and the bass cantata

“Ich habe genug” (with

concertante oboe) (BWV 53,

160 and 189, also solo

cantatas, are probably or

certainly not by Bach).

Nearly all these strikingly

chamber-musical, intimate

works were probably written

around 1730-32, and in

nearly all of them the

writer of the text could not

be determined to date. In

view of their marked

chronological proximity to

one another, it would seem

to suggest itself most

strongly that none other

than Bach himself was their

author. Around and just

after 1730 he evidently had

some particularly able

soloists among his pupils at

St. Thomas’ School, his

Leipzig students or other

helpers, and these special

circumstances - and probably

other reasons deriving from

practical considerations of

cantata performance -

stimulated him to experiment

for a few years with the

solo cantata, which his

Leipzig congregation had not

been accustomed to hear from

him up till then. That there

was no need for him to spare

the members of his ensemble,

here as in the big cantatas,

is particularly clearly

shown by what is probably

the earliest, the most

famous and the most virtuoso

of all these works: “Jauchzet

Gott in allen Landen”.

The cantata “Jauchzet Gott”

(BWV 51) was probably

composed in 1730, being

intended for the 15th Sunday

after Trinity (17. 9. 1730)

“et in ogni tempo”. It has

no apparent connection with

the Gospel for this Sunday

(Matth. 6, the unjust

Mammon), either textually or

musically, but its pious

jubilation truly does let it

appear liturgically suitable

“in ogni tempo”. What was

perhaps also a makeshift

allocation to the 15th

Sunday after Trinity thus at

least becomes

understandable, all the more

so in that the simple and

concise form of the work

does not allow of the

interpolation of a sermon

(as is the case with the big

cantatas in two sections);

its performance will thus

only have been possible at

the beginning or at the end

of the service. But here,

too, it will have seemed

questionable to the orthodox

Leipzig church people. The

extraordinary virtuosity of

the solo vocal part and of

the trumpet combined with it

in concerto style in the

first aria and the closing

“Alleluja” give it much of

the character of a concert

piece, of a resplendent (and

remarkably

“fashionable-Italian”)

exhibition of virtuoso

soloists in the style of the

great trumpet arias of

Alessandro Scarlatti and his

school. Of course, the

composer could not have been

Bach if he did not sound a

gentler and more intimate

note between these two

resplendent and extrovert

movements in C major. This

appears in the solemn,

striding quaver motion and

the touching gesture of

prayer in the A minor

recitative “Wir beten zu dem

Tempel an” (We worship at

the temple), in the A minor

aria, whose gently rocking

melody and rhythm are sure

to have been inspired by a

central idea in the aria’s

text: the faithful as God’s

children (“dass wir Deine

Kinder heissen”), and in the

skilllful chorale fantasia

that leads into the radiant

final “Alleluja”.

BWV 202, “Weichet nur,

betrübte Schatten ”(Depart,

gloomy shadows), is a

soprano cantata of an

entirely different kind. It

was possibly composed while

Bach was still conductor at

Köthen (1712-23), certainly

at a relatively early date,

and is a “secular” wedding

cantata, not intended for

the church ceremony but for

the domestic celebrations.

This explains both the

work’s camber music

instrumentation and its

text, which describes and

unites mythological

celebration of spring and

the spring of the marriage

couple’s love with a

charmingly naive erudition.

The happy basic mood of

these verses is matched by

the composition, which is

entirely attuned to bright

colours, gay tone-painting

and song and dance elements.

Thus the introductory G

major aria paints the

“betrübte Schatten” (gloomy

shadows) of winter only in

gentle pastel shades,

“Florens Lust” (Flora’s

pleasure), on the other

hand, in elegantly dotted

rhythms and song-like

sequences of motifs. The C

major aria “Phöbus eilt mit

schnellen Pferden” (Phoebus

hastens with fast horses),

accompanied only by the

continuo, depicts the

stamping of the horses’

hooves and the “hastening”

in leaping quavers and

rolling semiquaver runs.

Bach used this bass theme

again later in the final

movement of the G major

Violin Sonata with obligato

harpsichord.) The two

following arias let one solo

instrument each - violin and

oboe - play in combination

with the vocal part. “Wenn

die Frühlingslüfte

streichen” (When the spring

breezes blow), in E minor,

describes the gentle breezes

and Cupid “stalking” through

the fields in concise

ritornello form with gentle

dynamic gradings and a witty

play of motifs which, after

broadly conceived melodic

beginnings, repeatedly

changes into the warbling

motif repetitions of a

little ‘galant’ song. The

oboe aria (D major) “Sich

üben im Lieben” (To practice

loving) is a rhythmically

spicy, elegant dance song

though in a large-scale ‘da

capo’ form; the little final

song, a gay gavotte, is a no

less elegant piece of social

dance music that assembles

the entire ensemble once

again, thus concluding

Bach’s good wishes for the

young couple with a polite

compliment in the best

social taste.

Ludwig

Finscher

|

|

|

|